James Connolly is widely remembered for his heroic death in the 1916 Rising. Less well-known, tragically, is his main life’s work: the struggle for international socialism. More than once in his writings he argued that Gaelic Ireland before the English conquest was essentially a communist society.

The Irish rose in rebellion again and again throughout history because to them English rule represented

the system of feudalism and private ownership of land, as opposed to the Celtic system of clan or common ownership, which they regarded, and, I think, rightly, as the pledge at once of their political and social liberty […] The Irish system was thus on a par with those conceptions of social rights and duties which we find the ruling classes to-day denouncing so fiercely as “Socialistic.”

(Erin’s Hope, 1897)

This is a conception of ‘liberty’ which the 21st-Century world should take note of – liberty based on democratic common ownership of wealth, rather than the ‘liberty’ of rich people to pollute, exploit and destroy without hindrance.

According to Connolly, Gaelic Ireland right up to its destruction by Cromwell in the 17th Century was

…a country in which the people of the island were owners of the land upon which they lived, masters of their own lives and liberties, freely electing their rulers, and shaping their castes and conventions […] the highest could not infringe upon the rights of the lowest – those rights being as firmly fixed and assured as the powers of the highest, and fixed and assured by the same legal code and social convention.

(The Re-Conquest of Ireland, 1915)

Connolly drew on the concept of primitive communism advanced by Friedrich Engels (who also, by the way, wrote a history of Ireland and learned Irish):

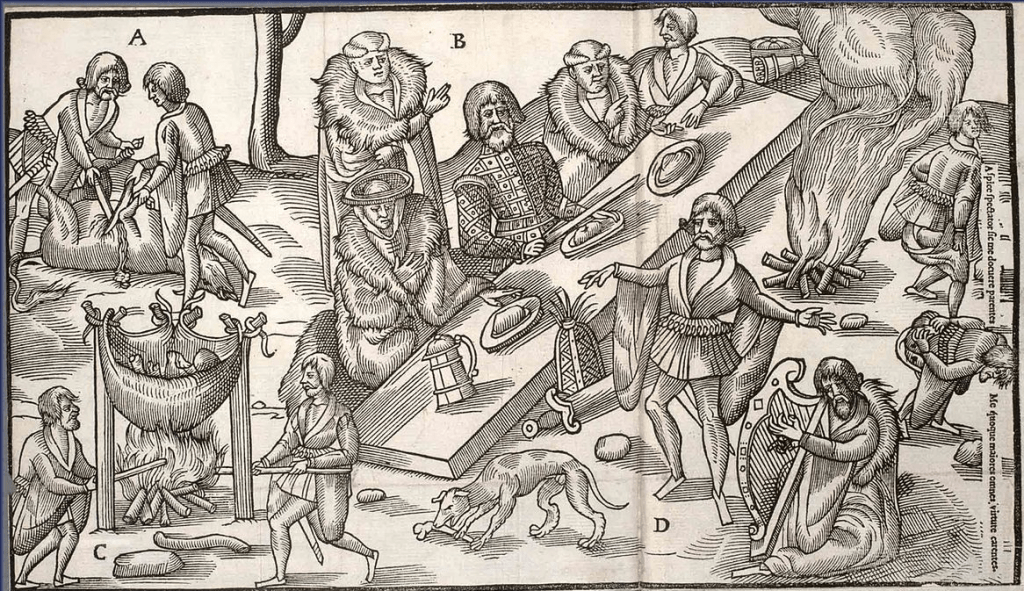

Recent scientific research by such eminent sociologists as Letourneau, Lewis Morgan, Sir Henry Maine, and others, has amply demonstrated the fact that common ownership of land formed the basis of primitive society in almost every country. But, whereas, in the majority of countries now called civilised, such primitive Communism had almost entirely disappeared before the dawn of history […] In Ireland the system formed part of the well defined social organisations of a nation of scholars and students […]

(Erin’s Hope, 1897)

These historical points were part of Connolly’s political mission: to champion the movement for Irish independence, but to take it further, to fight for social as well as political liberty. This was his contribution to debates around the Gaelic cultural revival.

But is it true?

Was Gaelic Irish society in any meaningful sense socialist? Or was this just one of those unfortunate examples of Connolly giving ground to romantic nationalism?

I want to test his claim against a range of historical sources. This is part 1 of a series that will be on-and-off; I will post three or four instalments over the next few weeks.

Want to get updates to your email address when I drop those posts? Subscribe here:

If Gaelic Ireland really was communist, it throws a new sidelight on the whole Celtic world.[i] It’s also very significant for those interested in the theory of primitive communism.

Connolly was not alone in believing that Gaelic Irish society possessed a democratic and communal social order. ‘Before the conquest the Irish people knew nothing of absolute property in land,’ wrote John Stuart Mill in 1868. ‘The land virtually belonged to the entire sept, the Chief was little more than the managing member of the association. The feudal idea which came in with the conquest was associated with foreign dominion, and has never to this day been recognised by the moral sentiment of the people.’[ii] Lawrence Ginnell in his impressive 1894 study of Brehon Law said that ‘the flaith [usually translated as ‘lord’ or ‘noble’] was properly an official, and the land he held official land, and not his private property at all.’[iii] In 1970 Peter Beresford Ellis painted a similar picture in the opening chapter of his History of the Irish Working Class.[iv]

By contrast, in much current writing on Gaelic Ireland we see heavy use of terms like ‘Lord and Subject,’ ‘Elite and Commoners’ ‘aristocracy’ and ‘hierarchy.’ This is an expression of a conflicting view, also of long standing, that ‘Irish society was rigidly stratified’[v] in the early medieval period. The same irreconcilable difference of opinion existed in Connolly’s day.

Gaelic Irish kings: Royalty or public servants?

In the first few posts of this series we’re going to take a look at one particular issue: the specific claim that a Gaelic Irish chief or king was ‘little more than the managing member of the association,’ ‘an official.’ If this is true he would be accountable and obliged to his people, relatively modest in status, something more akin to a public servant than to a member of a hereditary ruling warrior class.

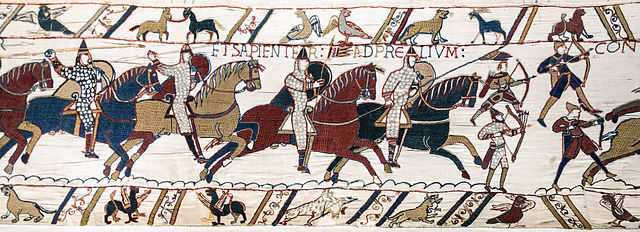

For perspective, we should take a look at Ireland’s contemporary neighbours. An 11th-century Anglo-Saxon cleric remarked, ‘the people have the choice to choose as king the one who pleases them: but after he is consecrated as king, he then has power over the people, and they are not able to shake his yoke from their necks.’[vi] They could elect their kings; this could also be applied to Ireland at the time. But by contrast Irish people, if they thought their king was not doing a good job, were required by law to ‘to shake his yoke from their necks.’ The English King Alfred was seen as sacred and could not be deposed by his own people. He could appoint reeves (officials), muster a fyrd (an army) and levy burdensome taxes, unlike his Irish counterparts. This gap only widened later in the Anglo-Saxon period, and that is to say nothing of Norman customs like primogeniture and knight service.[vii]

Chronology

In this series, we will deal with Irish kingship in the period between the Eighth Century and the Norman conquest of the late Twelfth Century. This span of time encompasses thousands of kings who ruled over hundreds of diverse tuaithe (peoples or petty kingdoms, singular tuath). Within that period, profound changes occurred: lesser kings became known as dux or taoiseach (leader or chief) and the over-kings and provincial kings extended their powers and prestige, fielded larger armies for longer periods further afield,[viii] and began to levy a form of taxation.[ix] Any attempt to describe the Gaelic Irish social order must begin by stressing this diversity and by acknowledging this general pattern of change – in general, towards more centralised kingship, and away from customs we might see as democratic or communistic.

Under English conquest from the 12th Century on things changed – unevenly and see-sawing, but they definitely changed – in the direction of feudal institutions along the lines of what we see in England. Norman lords had inspired greedy Irish kings to copy them – to turn tributes into rents, to turn clients into tenants. Jaski bears out this general point: from the twelfth century on, ‘free clients’ grew closer in status to ‘base clients,’ and the position of base clients worsened as the power of kings and flaiths grew.

On the other hand, Gaelic Irish custom remained strong even after centuries under conquest. English observers like Spenser and Davies in the 16th Century describe elective kingship, tanistry, etc. When we talk of how the Normans became ‘more Irish than the Irish themselves’ it’s not just that they started playing hurling and stealing cattle and speaking Irish. It’s a commentary on how they were assimilated into the Gaelic Irish system of common land ownership. But it was a two-way street. The legal superstructure of Irish society didn’t change much between the Normans and Cromwell but he society underlying it changed a great deal. The old ways were not finally broken, however, until the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, when we see the Plantations – waves of violence that exterminated around a quarter of the people and overthrew the social order.[xii]

Feudal relations could grow up inside the framework of the communal, democratic system of the Gaelic Irish – but could only go so far, until the final shattering of that framework in the 17th century.

Connolly lumped in all of pre-Cromwell Ireland into one description. But the further on we go in his chronology, the less Gaelic Irish society resembles what he describes. In his defense, this is political and not historical writing. He is making a political point – that common ownership of land prevailed until the Cromwellian rupture, that not just two nations but two social systems confronted one another in Ireland up to that point. This is true. But in the way he makes the point he drives a steamroller over Gaelic Ireland and flattens it out.

Everyone has to read Connolly. He’s brilliant. But don’t read him for a detailed and accurate history of Gaelic Ireland (or at least don’t begin and end with Connolly). He doesn’t offer one and, in fairness, he never pretended to.

Succession

How did a person get to be a king? In Norman England, kingship passed from father to eldest son. Gaelic Irish kings, on the other hand, were not born to rule but elected. Even the tánaiste (king’s deputy) was heir-apparent but not heir-designate. The electorate was narrow for the loftier kings but relatively broad for petty kings: provincial kings were elected by the titled persons of a province, while the king of a tuath was elected by all heads of households.[xiii]

Who could be a candidate? Family descent mattered a great deal, with scribes ‘pursuing endless genealogies to improbable beginnings’[xiv] in the interests of propaganda. ‘A non-kinsman does not take possession to the detriment of a kinsman,’ declared one law tract, to which a footnote by another legal scholar clarified that a candidate was entitled ‘if he be someone of the family [and] if he be right for the lordship.’[xv]

But hereditary claims were emphasised (even fabricated) by candidates precisely because succession could be contentious. The pool of candidates could be very wide; everyone who had the same great-grandfather. In addition, there was provision in the laws for illegitimate children and even non-relatives to contest the election. That a candidate must be ‘right for the lordship’ meant that it was at least as important for a candidate to possess febas (excellence or personal qualities).[xvi] Youth, old age, disability, incapacity or physical blemishes usually disqualified a candidate.[xvii]

(One legend tells of a king who had a lime-calcified brain thrown at him so that it stuck in his face. Because he was a really capable king, his people gave him a dispensation and let him rule.)

People in a contractual relationship with a flaith were divided into free clients and base clients, the former enjoying better terms than the latter. Base clients, even those related to the king, were singled out for disqualification. This suggests three interesting conclusions:

- that descent was secondary to social grade;

- that a free client could be king;

- and that it was known for a king to have base clients among his close male relatives.

These points challenge notions of a ‘rigidly stratified society’ and the last point suggests that we are dealing not with lofty family oligarchies but with broad kinship groups whose members were woven into the fabric of (often very small) tuaithe. The tuath was essentially a very big, broad family. Predictably enough, only a member could be the head of the family.

(As an aside, Fraser’s The Golden Bough mentions societies such as the Picts where the exact opposite custom held: the king of a community had to be an outsider.)

Inheritance did exist. Land and other property was divided between a king’s sons on his death. But that portion of his land which he only possessed through his title passed back to the community, to be given to whoever was next elected.

Heredity was a decisive advantage. But a candidate for kingship, whoever his ancestors were, had to demonstrate his own personal worth before the critical eyes of his peers.

Status

The free member of the tuath was not a subject of any king or lord. Even an individual in a contractual relationship with a king was not a subject or a vassal but a céile, a word which carries connotations of ‘partner’ or ‘companion’ and is usually translated as ‘client.’ All in all, Irish kings did not enjoy the exalted status of their contemporaries in Anglo-Saxon or Norman England. They were neither sacred nor above the law. According to the Old Testament, a king could not be deposed. But in Ireland the people had a duty to depose a ‘defective’ king, or else calamities would befall them.[xviii] A defective king was one who failed to repair infrastructure, who was stingy, who ripped off his own people, or who got his wounds on his back in battle (unless, the laws stipulate, he got those wounds on his back by running through the enemy lines).

Irish law had no sense of sublime majesty. Different categories of king were divided up into grades and their ‘honour price’ set down in bald numbers. Some professions, such as poet, judge or hostel-keeper, could attain the same honour price as a king.[xix]

Here we enter more disturbing territory, because honour price was measured in a unit of value called the cumal. The same word was used for a female slave. We need to let the dehumanising implications of that fact sink in, and then think about the general question of slavery. Connolly doesn’t mention it. Ginnell and Ellis deal with the issue, in my opinion not satisfactorily. This is a serious challenge to the idea of Gaelic Irish society as an equal, democratic, communistic society. We will deal with this question more fully in a future post.

You will have noticed a lot of ‘he’ and a lot of ‘his’ in the above points; that is because women could not hold political office. This suggests another topic for a future post: the position of women in Gaelic society, which was in some respects better than their position in other contemporary societies, but still bad. We need to consider this also in our judgement on Gaelic Irish society.

Next week in Part 2 we’ll continue our focus on the strange nature of Irish kingship. We’ll look at Irish kings at war; at the crazy array of social grades into which Irish society was divided; and at the question of wealth redistribution.

The cover image above is from Sláine: Time Killer, (Mills, Belardinelli, Fabry, Pugh, Talbot.) I’m a fan of of Sláine – read my review here. The image shows an Irish army preparing for battle in 1014.

[i] It is bold, to say the least, to draw conclusions about the Gauls in 100 BCE based on what some Irish monk wrote in 1000 CE, but people still do it; Ireland occupies a special place in Celtic studies because the Irish were the only Celtic people to produce a large amount of writing about themselves, as opposed to being written about by people like Julius Caesar when he could find time in between slaughtering them.

[ii] Mill, John Stuart. England and Ireland, Longman, Green, Read and Dyer, 1868, p 12

[iii] Ginnell, Lawrence. The Brehon Laws: A Legal Handbook, 1894. https://libraryireland.com/Brehon-Laws/Contents.php, ‘Section IV: Flaiths’

[iv] Connolly, James. Erin’s Hope, 1897, 1909, https://www.marxists.org/archive/connolly/1909/hope/erinhope.htm. See also Labour in Irish History (1910) and The Reconquest of Ireland (1915). https://www.teanglann.ie/en/fgb/flaith; P Berresford Ellis, A History of the Irish Working Class, Pluto Classics, 1972, 1996, p 14

[v] Frame, Robin. ‘Contexts, Divisions and Unities: Perspectives from the Later Middle Ages,’ and Ní Maonaigh, Máire. ‘Perception and Reality: Ireland c. 980-1229’ both in Smyth, Brendan (ed), The Cambridge History of Ireland, Cambridge University Press, 2018, pp. 535, 150, 153. Byrne, FJ, ‘Early Irish Society,’ in TW Moody and FX Martin (eds). The Course of Irish History 1967 (2011), p 45

[vi] Quoted in Godden, MR. ‘Ælfric and Anglo-Saxon Kingship.’ The English Historical Review, Vol 102, No. 405 (Oct, 1987), pp. 911-915. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/572001. Accessed 10 May 2021

[vii] Rosenthal, Joel T. ‘A Historiographical Survey: Anglo-Saxon Kings and Kingship since World War II.’ Journal of British Studies, vol. 24, no. 1, 1985, pp. 72–93. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/175445. Accessed 10 May 2021.

[viii] Simms, Katharine. From Kings to Warlords, The Boydell Press, 1987 (2000), p 11

[ix] Ní Maonaigh. p 150

[xii] Jaski. pp. 271-3

[xiii] Ginnell, ‘Section II: Irish Kings.’ ‘The king of a tuath was elected by the flaiths, aires and probably all heads of families in the tuath.’

[xiv] Hayes-McCoy, GA. Irish Battles: A Military History of Ireland, Gill & Macmillan 1969 (1980), p 16

[xv] Jaski. p 156

[xvi] Ibid. pp. 157-162

[xvii] Ibid. pp. 82-87

[xviii] Ibid. p 62

[xix] O’Sullivan, Catherine Marie. Hospitality in Medieval Ireland 900-1500, Four Courts Press, 2004, p 128. See also Jaski, p 174

8 thoughts on “Celtic Communism? Pt 1: James Connolly’s Celts”