‘My heart is heavy. My feelings seem to be split in two: I hate and despise the savage, cruel, senseless mob, but still I feel the old pity for the soldier: an ignorant, illiterate man, who has been led astray, and is capable both of abominable crimes and of lofty sacrifices!’

Anton Denikin, The Russian Turmoil; Memoirs: Military, Social and Political, 1920, Chapter xxxii

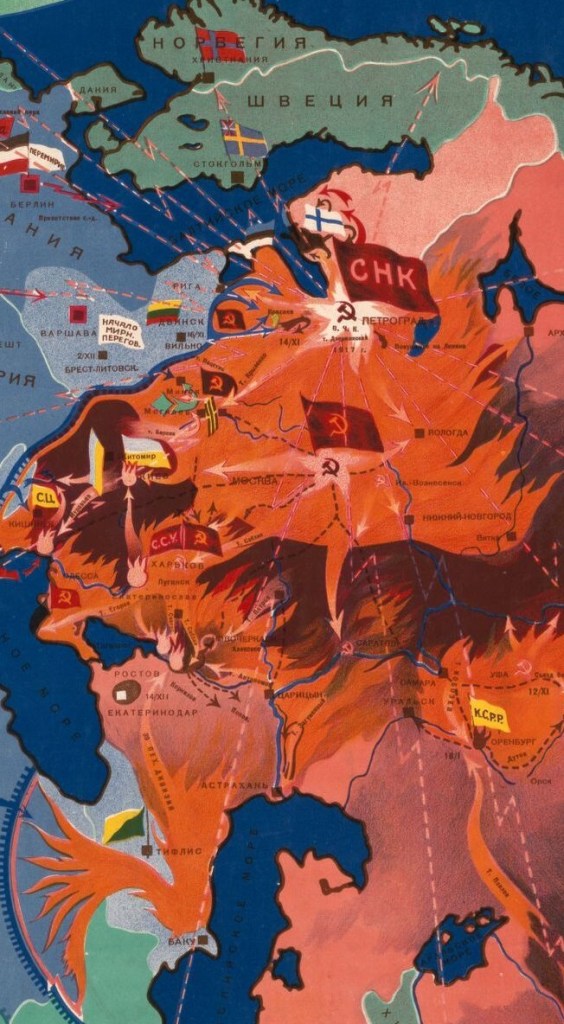

January 1918. Four thousand armed men had gathered by the Don River to begin a counter-revolution that would shake Russia for years to come. This week we’re going to take a closer look at the White Guards, those who rose up in arms against the October Revolution. Then we will examine how things went down when they had to face the Red Guards for the first time.

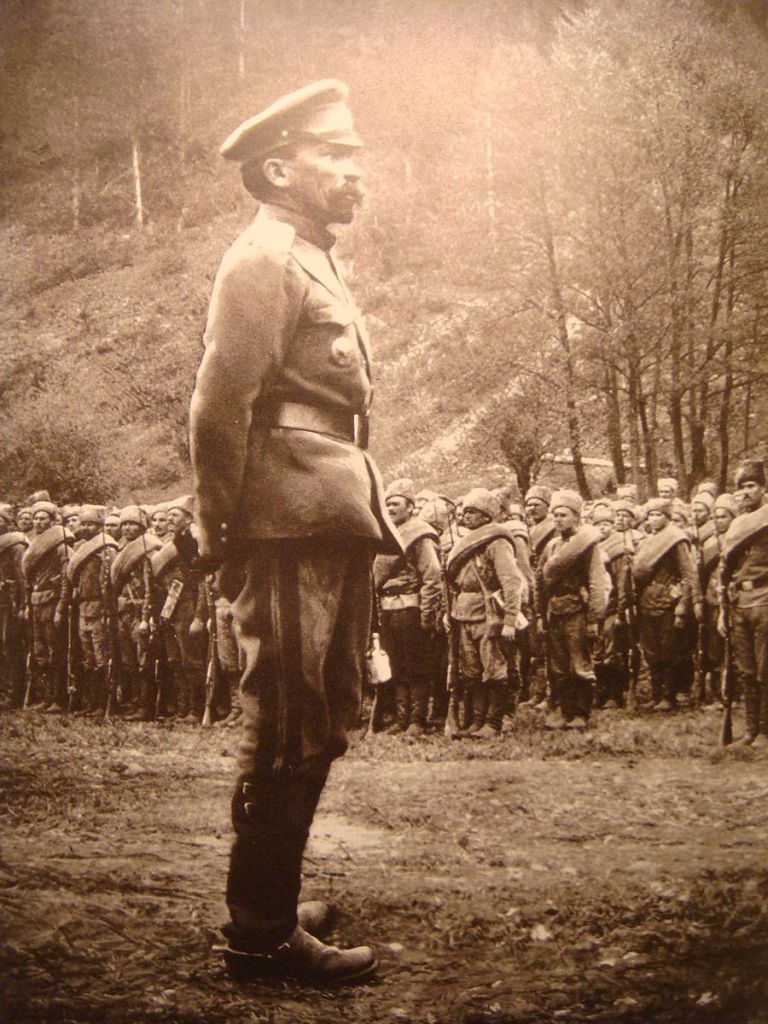

Anton Denikin first met Lavr Kornilov on the plains of Galicia at the start of the World War. The two Tsarist generals served side-by-side on the same front in what Denikin called ‘incessant, glorious and heavy battles’ as their thousands of soldiers fought their way over the Carpathian Mountains and down into Hungary. Denikin was impressed by Kornilov’s ability to train up ‘second-rate’ units into ‘excellent’ condition, by his scrupulousness and by his personal prowess. Later in the war Kornilov became a celebrity after he broke out of an Austrian prison.Denikin was big and avuncular and Kornilov thin and severe, but both came from humble backgrounds and both were utterly dedicated to the army as an institution, and these facts helped them to see eye-to-eye.

Military officers saw themselves as a caste removed and above society. Around 1898 a cavalry lieutenant had explained his perspective on the world: at the centre, highest in his regard, were his own regiment. Next came other cavalry units, then the rest of the army. Beyond – the ‘wretched’ civilians. First came the relatively ‘decent’ civilians, then ‘the Jews’, then ‘the lower classes’ and last of all the socialists, communists and revolutionaries. In regard to the last group, ‘Why these exist nobody knows, and the emperor really is too kind. One ought to be able to shoot them on sight.’ A lieutenant in 1898 might be a colonel or general by 1918.

Back in the old days, Russian military officers were generally noble or at least bourgeois in origin. Each generation of officers dated the ‘good old days’ to a decade or two earlier, but already by the 1870s a third of officers hadn’t even finished primary school.

But in these latter days, according to Denikin, the gates of the officer training schools had been flung open to ‘people of low extraction,’ with the result that the officer corps had ‘completely lost its character as a class and as a caste.’[1] (Denikin apparently subscribed to the principle of Groucho Marx: ‘I don’t want to be part of any club that would have me as a member.’) The old bonds that had held the army together – the church, the monarchy – grew weak. What was to blame for this weakening – the decay of the moral fabric of society? The corrupting influence of city life? Workers were now motivated by base material desires rather than spiritual riches; the ikon in the corner of the workshop no longer satisfied them.

The war with Japan in 1905 and its attendant revolution were disasters for the prestige of the Russian state. It appeared few lessons were learned for the Great War. In 1914-15 the old army – what was left of it ‘as a class and as a caste’ – was broken under the German, Austrian and Turkish guns. There were crippling shortages of rifles, uniforms and shells. Over two million soldiers of the Russian army perished in the war. The civilian deaths, the wounded, prisoners of war – each of these categories also numbered in the millions.

Many officers fought with great courage. But they saw their gains thrown away through incompetence, corruption, stupidity and shortages. They grew angry with the government.

According to General Denikin, ‘It is hardly necessary to prove that the enormous majority of the Commanding Officers were thoroughly loyal to the monarchist idea and to the Tsar himself.’[2] Accordingly, they blamed the Tsar’s German wife, and they obsessed about Rasputin, blamed everything on his ‘corrupting influence.’

Mutiny

The February Revolution came. The high-ranking officers, blindsided, suffered a tumult of emotions. They were disappointed in themselves – they should have engineered a ‘palace coup’ in order to head off this movement. They were angry at the moderate politicians who had stepped into the void – these scoundrels had abolished the monarchy. They were mortally afraid of the tidal wave of workers and of the mutinies in army and navy. The peoples of Finland, Ukraine, Poland, the Baltic states, Central Asia and the Caucusus were ‘Russian in spirit and in blood’[3] – but now, for some reason, they wanted self-determination. This amounted, in the eyes of the officers, to the dismemberment of holy Russia.

Something good might yet come out of the Revolution, and it was no use in any case trying to swim against the stream. It could perhaps be guided into safer channels. Denikin would carefully distinguish between ‘the real Democracy,’ by which he meant ‘the bourgeoisie and the civil service’ and the ‘Revolutionary Democracy’ – the socialist parties, whose supporters were ‘semi-cultured’ and ‘illiterate.’ If the ‘real Democracy’ could get the upper hand over the ‘Revolutionary Democracy,’ things might yet be salvaged.

But the portents were not good. Chapter VII of Denikin’s memoirs describes his reunion with his old comrade-in-arms Kornilov at a dinner in the house of the War Minister in late March. Denikin found him tired, morose and pessimistic. The condition of the Petrograd garrison was beyond comprehension to Kornilov: they were holding political meetings, engaging in petty trade, hiring themselves out as private guards. He spoke of ‘the inevitability of a fierce cleansing of Petrograd.’ Already the highest-ranking officers were contemplating coups and civil war. During the street demonstrations of April, Kornilov proposed to disperse the crowds with artillery and cavalry – and even though the government rejected this idea, he made practical preparations to do so.[4]

Soon, thanks to a Soviet decree, officers had to answer to elected committees of the rank-and-file. This was an incredible humiliation for men born and raised and trained to value rigid hierarchy. The death penalty was abolished; the officer no longer held power of life and death over the men. The men, it appeared, now held that power over the officers. This was confirmed when sailors massacred over forty officers in one incident.

The officer corps hated the new Provisional Government for pandering to the Soviet, and they loathed the Soviet itself. The soldiers’ delegates were, they complained, a bunch of clerks and shiftless rear garrison men. The proceedings of the Soviet were a display of ignorance and coarseness that embarrassed Russia before the whole world.

And there were too many ‘foreigners.’ Pointedly, Denikin in his memoirs listed by nationality the personnel of the Presidium of the Soviet Central Committee:

1 Georgian

5 Jews

1 Armenian

1 Pole

1 Russian (if his name was not an assumed one)

To him, this was proof that the Soviet was dominated by an ‘alien element, foreign to the Russian national idea.’[5]

This quote from Denikin gives us a good insight into how the White Guard officer saw the world. When members of the minority groups held high office, they were suddenly no longer ‘Russian in spirit in blood,’ but ‘foreign,’ ‘alien.’

When the officers spoke of the socialist leader Trotsky, they always called him ‘Bronstein’ or ‘Bronstein-Trotsky,’ as if they were thereby making an important point.

Kornilov

The Constitutional Democrat party was a bastion of Denikin’s ‘real Democracy:’ it was a party of business-owners and bureaucrats. After the July Days, a near-revolution in Petrograd, the Constitutional Democrats and the top brass of the military deepened their collaboration.

The figurehead of this movement was General Lavr Kornilov. At a conference in August 1917 the Constitutional Democrats carried him on their shoulders and cheered him to the rafters.

General Kornilov made his move in August. But the attempted coup was not just a failure; it backfired and strengthened the Bolsheviks (China Miéville’sOctober, published by Verso Books in 2017, contains a lively account of this episode).

Denikin was one of Kornilov’s co-conspirators. After the failed coup, Denikin ended up in a cell seven foot square. In early mornings, soldiers would cling to the bars of the window to curse and threaten him:

Wanted to open the Front […]’

‘[…] sold himself to the Germans […]’

‘[…] wanted to deprive us of land and freedom.’

‘You have drunk our blood, ordered us about, kept us stewing in prison; now we are free and you can sit behind the bars yourself. You pampered yourself, drove about in motor-cars; now you can try what lying on a wooden bench is, you ——. You have not much time left. We shan’t wait till you run away—we will strangle you with our own hands.

Denikin covered himself with his cloak. In that moment all he could think was: ‘What have I done to deserve this?’

He thought back over his life – humble origins, promotion on his own merits, valour in combat. By the standards of the institution he served, he had always been relatively kind to the men under his command, in that he declined to beat them up.

As he thought over it all, his rage mounted. He rose, throwing aside his cloak.

‘You lie, soldier! It is not your own words that you are speaking. If you are not a coward, hiding in the rear, if you have been in action, you have seen how your officers could die.’

His tormentors, awed by his words and unable to contradict them, retreated.

Not all the soldiers were hostile. ‘On the first cold night, when we had none of our things, a guard brought [General] Markov, who had forgotten his overcoat, a soldier’s overcoat, but half an hour later—whether he had grown ashamed of his good action, or whether his comrades had shamed him—he took it back.’

But Kornilov was not daunted. The attempted coup and its aftermath represent the germinating seeds of the White Armies. He and all his co-conspirators ended up imprisoned at Bykhov monastery. Bykhov was just down the road from the general staff HQ. There Generals Alexeev and Dukhonin kept in close contact with him. So Kornilov, through proxies, was able to carry on his work and to build an underground league of officers and cadets. Another co-conspirator, the Don Cossack General Kaledin, was along with Alexeev preparing a base for counter-revolution in the Don Country in the South.

The Politics of the Kornilov Movement

Kornilov and his supporters opposed the Soviet, but what was their own vision for the future of Russia and its Empire? They were in favour of a military dictatorship, but it would not remain in power forever. Its task would be to ‘restore order.’ Once order was restored – in other words, once all the working-class leaders were dead or imprisoned and their parties crushed, once the Soviet was liquidated and all weapons taken out of the hands of workers, once the soldiers had been forced back into the trenches, and all the national minorities induced to temper their demands – then, and not until then, the power would be handed to a legitimate government. Perhaps it would be led by another absolute monarch like Nicholas. But some of the officers were for a constitutional monarchy, and some even for a republic. There could be elections once order was restored. As soon as the masses were put back in their place and there was no chance of the socialists winning, it would be safe to have an election.

It is sometimes said that the White movement embraced the full spectrum of political opinion from monarchist to social-democrat. There were in reality no leftists among the Kornilovite officers; the entry of ‘moderate socialists’ into the White camp was a later (and a brief and unhappy) development, which we will deal with in later chapters.

But the White officers themselves placed very little stock in all these political questions. They uttered the ‘p’ word with the distaste they otherwise reserved for ‘Bronstein.’ The political questions could be settled after order was restored. They were mere soldiers and not politicians – thank God! They had neither the right nor the desire to pre-determine the results of some future election.

From Denikin’s memoirs, the reader can see that what really mattered was not the form of government that was to follow; what mattered was the ‘fierce cleansing.’

But these plans were left bobbing in the wake of history. The October Revolution struck. The Provisional Government and its few defenders were, as we have seen, hapless. The Kornilov movement took belated action.

The cadets, officers and Cossacks rose up in Moscow and in Petrograd in a bloody series of episodes over several days. It was in Moscow that the counter-revolutionaries first received the nickname ‘White Guards’ from their enemies. It was a reference to the French Revolution; white was the colour of the Bourbon monarchy. If it was supposed to be an insult, it backfired. The White Guards wore the name with pride. But in both cities they were defeated. In Petrograd their leader, General Krasnov, was released on parole. In Moscow the surrendered White Guards were all allowed to walk away, some still carrying their arms. Even Antony Beevor, whose book Russia: Revolution and Civil War paints an ugly picture of the revolutionaries, acknowledges the magnanimity of the Reds on this occasion.

After defeat in the two great cities, Generals Kornilov and Alexeev decided to play a longer game. They gave the order to rendezvous in the far south of Russia by the river Don, where they had reportedly stockpiled 22,000 rifles.[6]

Thousands of individual officers began the journey south. Peasants and soldiers did not show the same clemency as the authorities in Petrograd and Moscow. ‘The fugitive officer en route for the south became an outlaw figure for the soldiers, to be killed on sight.’[7] But they persevered. Many survived the journey by throwing aside the red shoulder-boards that marked them out as officers. Others disposed of their uniforms entirely, and went on to fight in civilian clothes.

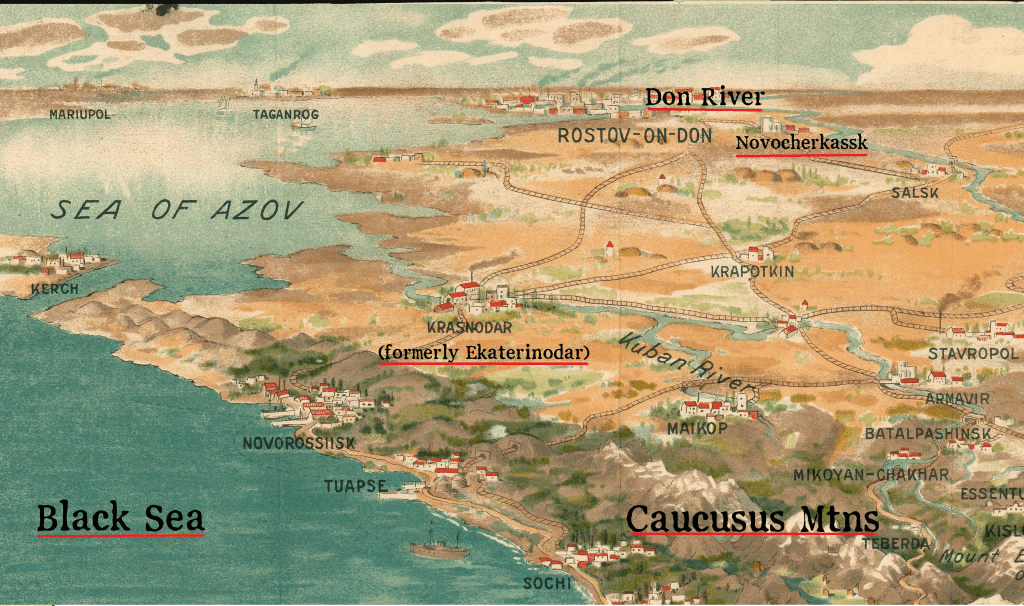

Kornilov simply rode out of his prison and set off for the Don. His ‘guards’ had joined him. They fought their way across the land. When Kornilov reached Novocherkassk by the Don he found General Alexeev and four hundred volunteers already mustered. The weeks passed and four hundred grew to four thousand as more officers, cadets and students arrived.

THE COSSACKS

These southern lands, north of the Caucusus mountains and between the Black Sea and the Caspian, had in living memory borne witness to a war more fierce and total than the Civil War. In the Nineteenth Century the Russian Empire had massacred and exiled the Muslim Circassian people. The Cossacks settled on rich black soil stolen from the Circassians. They adopted the style of the vanquished: long narrow-waisted coats and silver-inlaid daggers. Non-Cossack immigrants flooded in later, and they were despised by the Cossacks and called ‘aliens.’

The Cossacks fought on horseback with swords and lances and carbines. Again and again the state had sent them in to crush protests. Now, true to form, the Don Cossack leaders had given a safe haven to the Volunteer Army.

But the Cossack lands were not a single conservative block. For many the supposed privileges were a burden. One-third of the Cossacks were poor, and equipping themselves for war put them in permanent debt. The Cossacks were outnumbered by their poor tenants – the so-called aliens – and oppressed by the big landlords. In the cities and towns there were artisans and workers influenced by the left-wing parties.

For the young Cossacks, the experience of the World War was shattering. For three years, ‘Russian soldiers were sent into battle without rifles or were deliberately shelled by their own when, in their trenches, they were understandably reluctant to go over the top.’[8] The young Cossacks witnessed all this, and they shared trenches and bivouacs with town folk who talked of revolution. By 1917 the refrain of the young Cossacks was: ‘We must saddle our horses and go to the Don; the war is pointless.’[9]

So they made the long journey home through lands teeming with revolution. At the frontlines, officers had kept order by beating and killing the rank-and-file soldiers. Now, as an army of nine million men collapsed, many an officer was shot by the railway stations and roadsides. When the Cossacks came riding back into their villages, the old men called them cowards and traitors, and said they had been bought off by the Reds or by ‘the Jews.’ But the young Cossacks had met and talked with these Reds, these Bolsheviks. The Revolution promised them an end to this war and to the military obligations, and a settlement of the land question. The young frontline veterans, the frontoviki, were uneasy at the presence of the Volunteer Army, at the sight of officers in their distinctive shoulder-boards mustering in the Don country for counter-revolution.

THE STRUGGLES ON THE DON AND KUBAN

Even before the October Revolution, local Soviets had taken power in eighty different towns. After October, the dam burst. Workers and peasants rose up in town after town, village after village, and bands of Red Guards took to the railways to spread Soviet power to wherever the old regime held on.

There were workers’ uprisings in Rostov and Taganrog, two towns by the Don. Counter-revolution soon followed: Volunteers and Cossacks crushed the risings ‘and [shot] the captured Bolshevist members of the Rostov Soviet.’[10]

The leader of the Don Cossacks was Ataman Kaledin, a cavalry general who had commanded an entire army in the Great War. He had been part of Kornilov’s coup attempt, though the Provisional Government had never dared to come after him for fear of kicking the Cossack beehive.

In spite of their common struggles and their successes in Rostov and Taganrog, Kornilov found Kaledin less than welcoming. The Volunteers were forbidden to carry arms in the Cossack capital Novocherkassk. Kaledin must have known that his Cossacks were not all of one mind, and that too open an allegiance to the White Guards could provoke a reaction. He declined to deepen the collaboration, and the Volunteer Army were packed off to the nearby town of Rostov.

Kaledin and Kornilov faced a favourable situation. To the east the Orenburg Cossacks had risen up. To the west a Rada or parliament had taken power in Ukraine. This was a nationalist movement which opposed the Bolsheviks. The Volunteer Army would make uneasy bedfellows with Ukrainian nationalists, whose claims to autonomy they rejected, but the Rada had given the officers free passage over their territory while arresting Red Guards. The task, therefore, was to strike out over Ukraine and link up with the Rada in Kyiv and form a solid front of counter-revolution in the south.

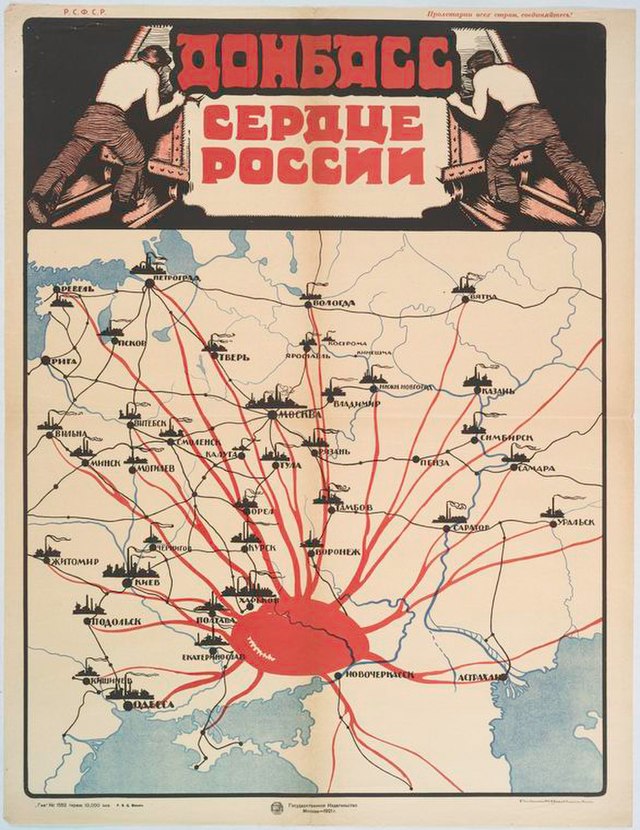

Kaledin led his Cossacks in an invasion of the Donbass region of Ukraine. This was, as we mentioned in Part One, the area where Kliment Voroshilov had worked as a miner, farm labourer, shepherd and metalworker before his sixteenth birthday.

Now workers like Voroshilov took up arms and barred the path of the Cossacks. There was no shortage of arms: rifles and machine-guns poured into the region from Moscow and Petrograd, and in every mining and factory town Red Guard units sprang up – here a few hundred fighters, there a few thousand. Armoured trains thundered in bearing Siberians, Latvians, sailors and Red Guards from the big cities. The Cossacks fled back to the Don.

We have now reached the moment at which we began, with thousands of Red Guards taking the railways south to the Don Country as 1917 turned to 1918. When they reached the Donbass, the Reds divided their forces. Most rolled on to Kyiv to overthrow the Rada, led by a former Tsarist officer named Muraviev who had reinvented himself as a revolutionary and was most likely an adventurer. The battle in Kyiv was bloody, with atrocities on both sides and Muraviev indulging in an early excess of terror, driven by ugly prejudices against Ukrainians.

Meanwhile about 16,000 went south to the Don to face Kornilov and the Volunteer Army.

The Cossacks decide

In a movie or a videogame, the Red Guards would no doubt have met the White Guards in a field somewhere and fought a single decisive clear-cut battle. In that situation the Whites would have won. The four thousand Volunteers knew how to fight, and the Cossacks were numerous and fierce. The Reds were far from home, poorly-organised and barely trained.

But there was no straight fight. These were not extras or NPCs, but human beings with doubts and fears. Each side met the other in a halting, hesitating way, one small detachment blundering into another; one outflanking and the other retreating, each unsure of the ground it stood on politically and tactically, with frequent ceasefires and negotiations. The fight would jump back and forth from one railway junction or small town to the next.

The Red Guards were more in their element behind enemy lines. Small numbers were sent ahead into the Cossack lands armed not with rifles but with documents such as the Soviet government’s December 1917 appeal to toiling Cossacks, promising a settlement of the land question but guaranteeing that they would not touch ‘simple soldier Cossacks,’ and declaring them free of the old military obligations that had put the poorest into permanent debt.[xi]

All this work paid off. On January 10th a Congress of Cossacks met at Kamenskaya. It was the birth of a movement of Red Cossacks. Enraged, Ataman Kaledin sent troops to arrest the delegates. But these troops went over to the Soviets. From this point on, Kaledin lost more and more soldiers every day – not to shells or bullets but to political arguments. The Don Cossacks had suffered a decisive split between rich and poor, old and young, village and frontline.

The Volunteer Army was still superior in discipline and training. On January 15th near Matveyev Kurgan, the burial mound of a legendary outlaw, a Red force of 10,000 suffered a bad defeat. But Matveyev Kurgan is a few hours’ walk from the town of Taganrog. The workers there had risen up before and been crushed by Volunteers and Cossacks. Now they struck again as soon as they heard the Reds were nearby. There followed two days of street fighting that ended on January 19th when the Whites were chased out. Reportedly, fifty captured cadets were brutally massacred by the workers. The revolution had returned to Taganrog, a day’s march from Rostov. Meanwhile a second Red force of 6,000 was advancing on Novocherkassk. Kaledin’s loyalists were not numerous enough to stop them. All they could do was retreat, burning railway stations and tearing up tracks as they went.

Kornilov could see that the game was up for Ataman Kaledin and his Don Cossacks. On paper, the Don Host numbered tens of thousands. But politics had intruded into military calculations. Many had gone over to the Reds, and of those who had not, most would not answer when Kaledin called.

But to the south across the steppe was the country of the Kuban Cossacks. The Whites hoped that the Kuban Cossacks might prove more solid. Kornilov and his Volunteer Army packed their bags, shouldered their rifles and marched out onto the steppe. The Don Cossacks were incensed at this betrayal. There were shots fired at the White Guards as they fled the Don Country.

The Volunteers had escaped out of the reach of the Red Guards from Moscow and Petrograd. But, as we will see below, wherever they went the revolution was close behind, or even lying in wait.

Ice March

Kornilov could see that the game was up for Ataman Kaledin and his Don Cossacks. On paper, the Don Host numbered tens of thousands. But politics had intruded into military calculations. Many had gone over to the Reds, and of those who had not, most would not answer when Kaledin called.

But to the south across the steppe was the country of the Kuban Cossacks. The Whites hoped that the Kuban Cossacks might prove more solid. Kornilov and his Volunteer Army packed their bags, shouldered their rifles and marched out onto the steppe. The Don Cossacks were incensed at this betrayal. There were shots fired at the White Guards as they fled the Don Country.

The Volunteers had escaped out of the reach of the Red Guards from Moscow and Petrograd. But, as we will see below, wherever they went the revolution was close behind, or even lying in wait.

ICE MARCH

The time was out of joint. In February, the Soviet government changed the calendar so that it was in step with the rest of the world. Overnight Russia leapt ahead by two weeks. In South Russia, time was passing quickly in more ways than one. Ataman Kaledin, who had commanded a whole army under the Tsars, could now call on only 100-140 men.

He blamed Kornilov.

‘How can one find words for this shameful disaster?’ he said in a speech before the Cossack assembly. ‘We have been betrayed by the vilest kind of egotism. Instead of defending their native soil against the enemy, Russia’s best sons, its officers, flee shamefully before a handful of usurpers. There is no more sense of honour or love of country, or even simple morality.’[xii]

After this speech, Kaledin retired to his rooms in the Ataman’s Palace and shot himself in the heart.

By the end of February Novocherkassk and Rostov had fallen to the Reds. A Don Soviet Republic was founded, with an SR Cossack named Podtelkov as its president. The last supporters of the late Kaledin galloped out into the wilderness, praying for better days.

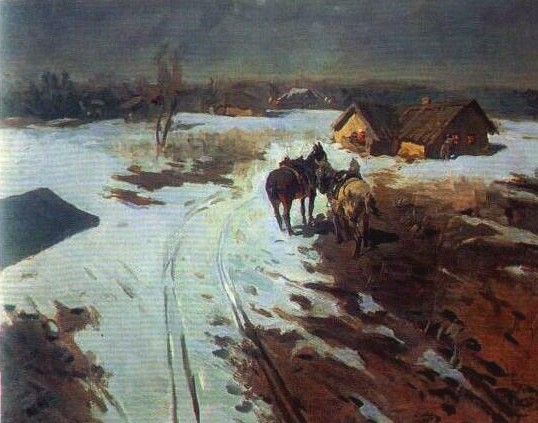

General Kornilov and his Volunteer Army, meanwhile, had marched out onto the Kuban Steppe, several thousand officers and civilians burdened with heavy artillery and carts full of the sick and wounded. Their journey went down in history as the First Ice March.

…a long column of soldiers wound its way out of Rostov, marching heavily over the half-melted snow. The majority were wearing officers’ uniforms […] Behind the numerous wagons of the baggage train came crowds of refugees: elderly, well-dressed men in overcoats and galoshes, and women wearing high-heeled shoes. […]

‘Have you anything to smoke?’ a lieutenant asked Listnitsky. The man took the cigarette Eugene offered, thanked him, and blew his nose on his hand soldier-fashion, afterwards wiping his fingers on his coat.

‘You’re acquiring democratic habits, lieutenant,’ a lieutenant-colonel smiled sarcastically.

‘One has to, willy-nilly. What do you do? Have you managed to salvage a dozen handkerchiefs?’

The lieutenant-colonel made no reply. Tiny green icicles were clinging to his reddish-grey moustache.

From And Quiet Flows the Don, Mikhail Sholokhov, 1929; trans Stephen Garry 1934, Penguin Classics 2016, pp 495-496

The officers were facing this bleak expedition in the hope that they could link up with the Kuban Cossack Host.

But the Revolution made its way to the banks of the Kuban river while the Volunteers were still toiling over the steppe. When they reached the Kuban Cossacks, they found the same thing they had left behind: a Cossack host that had mostly gone over to the Reds. And beyond lay the Caucusus Front, where hundreds of thousands of veterans had mutinied and were coming north to join the revolution.

February turned to March and spring did not come. Rain gave way to snow and cold winds, and the Volunteers’ clothes were crusted with ice. Under pursuit, forced to avoid railways and settlements, they fought forty battles in fifty days.

‘Take no prisoners. The greater the terror, the greater will be our victory.’[xiii] To judge by these words of Kornilov, the suffering only made them more determined.

In April their fortunes seemed to turn. They joined up with a force of White Kuban Cossacks, bringing their total fighting strength to 6,000 and adding two more generals to their already impressive collection. They decided to march on the Kuban capital, Ekaterinodar (now Krasnodar), a city of 100,000 people.

They had escaped from the Red Guards of Petrograd and Moscow. They needed the resources of a city; but where there were cities there were workers, and where there were workers there were Red Guards.

From April 10th to 13th the Volunteer Army attacked Ekaterinodar. But 18,000 Red Guards were waiting for them. The vast numbers of people who flooded into the Red Guards whenever the Whites raised their head was a sign of the popularity of the Revolution. The fact that the Whites could at first only muster a few thousand is a reflection of their narrow – though very determined – support base.

Hundreds of Whites were killed the fighting. Kornilov had made his HQ in a farmhouse on the edge of town; on the morning of the 13th a shell scored a direct hit on the roof. Kornilov was killed. The Volunteer Army gave up the fight and once again fled out onto the steppe.

The End of the First Wave of Civil War

On April 23rd the Soviet leader Lenin declared victory: ‘It can be said with certainty that, in the main, the civil war has ended… on the internal front reaction has been irretrievably smashed by the efforts of the insurgent people.’

Even before the Volunteer Army’s defeat at Ekaterinodar, Lenin had sounded a similar note: ‘A wave of civil war swept over all of Russia, and everywhere we won victory with extraordinary ease.’[xiv]

There had been serious fighting on every point of the compass. A Tsarist army corps made up of Polish soldiers revolted in Belarus. A street battle erupted in Irkutsk in Siberia. A warlord named Semyonov raided and rampaged beyond Lake Baikal. Cossacks in the south of the Ural Mountains rose up and seized Orenburg.

Everywhere the result was the same. In response to these challenges, local workers and poor peasants volunteered for Red Guard units, usually in their thousands or tens of thousands. There was no Red Army yet. This was the time of the otryad, the informal ‘detachment’, some formed on local initiative, others sent out from Moscow or Petrograd; numbering anything from a few dozen to thousands; armed with anything from a few rifles to an armoured train (or even, in the case of Irkutsk, bows and arrows[xv]). Just like on the Don, everywhere political appeals were decisive. The Red Guards knew how to disarm the enemy with class politics. When that failed, they had their rifles.

Victor Serge, a communist who later criticised his own side for excessive use of violence, wrote that this wave of struggle was won ‘with neither excesses nor terror.’[xvi] It’s clear that he means terror directed and sanctioned by the Soviets; elsewhere he makes no secret of the fact that rogue bands of sailors and soldiers were killing officers and carrying out massacres like in Sebastopol. Important outliers in Kyiv and Kokand, both in February 1918, should be noted. But when two right-wing figures were murdered in their hospital beds by sailors in January 1918, the Soviet press condemned this atrocity. In general the noises from key Bolshevik leaders indicated that they believed the Russian revolution, unlike the French, could avoid terror and mass executions.

At this point the Soviet regime was still a democratic one. The government was a coalition between the Bolsheviks and the Left SRs. The Third Congress of Soviets met on January 15th, around the time the Don Cossacks split. At this congress we see not just Bolsheviks and Left SRs but also Right SRs, Menshevik-Internationalists and Anarchists. It’s striking that the Right SRs were tolerated even though they had taken part in the uprisings in Moscow and Petrograd.

This was how things stood in the military situation and the political regime in early Spring 1918. The violence appeared to be over.

That spring, a renewal of the war with Germany seemed far more likely than a new wave of civil war. At the end of April the forces of the White Guards consisted of several thousand men, encircled and leaderless, on a blasted steppe on the very edge of Russia. At that moment the first Red army units had been formed, but they did not face the Don or the Volga; they faced the German armies to the west.

But with hindsight we know that the real Civil War had not even begun. Starting in May, a chain of catastrophes would fan the dying embers of armed struggle to an inferno that would not die down until the end of 1920, and that would still be blazing in parts of Russia as late as 1923. What the Red Guards had just endured was nothing compared to what was coming down the line. A bloody summer lay in wait. The war of irregular ‘detachments’ that had triumphed by the Don and Kuban rivers would fall far short of the challenges. To survive, the Soviet republic would need to build a regular professional army.

Transitions, sound effects, music and dialogue on the video and audio versions of these podcasts are not my property but are included under fair use. Credits for the audio version of this post are as follows:

Music from Alexander Nevsky by Sergei Prokofiev.

Intro from Anastasia (1997, dir Don Bluth and Gary Goldman)

Dialogue from Fall of Eagles, Episode 12 (1974, Elliot & Burge, BBC)

Transitions from Battlefield 1: In the Name of the Tsar (2017, Dev. Dice)

[1] https://www.gutenberg.org/files/43680/43680-h/43680-h.htm Chapter VII

[1] Denikin, Anton. The Russian Turmoil. Memoirs: Military, Social, and Political, 1920. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/43680/43680-h/43680-h.htm. p 17

The cavalry lieutenant is quoted in Reese, Roger, Red Commanders, Press of the University of Kansas (2015), p 15 and the detail about primary school completion among officers in the 1870s comes from the same source.

In addition to the sources listed here as direct citations, I have constructed the narrative drawing heavily from Smele (The ‘Russian’ Civil Wars), Mawdsley (The Russian Civil War), Smith (Russia in Revolution) and Serge (Year One of the Russian Revolution).

[2] Denikin, p 16

[3] Denikin, p 21

[4] Trotsky, LD, History of the Russian Revolution, Volume I, Gollancz, 1932, Chapter XVII, p 353-358

[5] Denikin, 91

[6] Kirienko Yu. K. KrachKaledinshchyna. Accessed and translated at Leninism.su. Another document from the same website to which I have referred is AM Konev, Red Guard on the Defense of October [sic; Google translate] https://leninism.su/revolution-and-civil-war/4142-krasnaya-gvardiya-na-zashhite-oktyabrya50.html. The documents on this site are extracts from works by Soviet scholars, but they are abridged and edited in suspicious ways – ellipses cover the defeat at Matveyev Kurgan, for example. Accordingly I have relied on these documents only for secondary matters, for the odd detail or quote, not for major questions.

[7] Serge, Victor. Year One of the Russian Revolution, p 123

[8] Carleton, Gregory. Russia: The Story of War, Harvard University Press, 2017, p 146

[9] Kirienko

[10] Serge says the Cossacks refused to take part, but Kirienko names the Cossack leader Nazarov as the one who crushed the Rostov uprising. The detail about the Rostov Soviet members being shot comes from a timeline at the end of Wollenberg’s book The Red Army: https://www.marxists.org/history/ussr/government/red-army/1937/wollenberg-red-army/append02.htm

[xi] Carr, EH. The Bolshevik Revolution Volume 1, Pelican Books, 1950. p 300-301

[xii] Serge, 125

[xiii] SA Smith, Russia in Revolution, ‘Violence and Terror,’ beginning p 196

[xiv] Mawdlsey, The Russian Civil War, (Birlinn, 1982, 2017) p 29, 38

[xv] According to AM Konev, the Reds took out White machine-gunners using ‘well-aimed arrows from among the indigenous Siberian hunters’.

[xvi] Serge, Victor. From Lenin to Stalin, Pioneer Publishers, trans Ralph Manheim, 1937. https://www.marxists.org/archive/serge/1937/FromLeninToStalin-BW-T144.pdf. p 28.

11 thoughts on “02: White Guards”