Listen to this post on Youtube or in podcast form

On a sunny day in early June 1918 the Bolshevik sailor Raskolnikov, who had a habit of being present when history was unfolding, received a telephone call from Lenin. He hurried to the Kremlin where he met Lenin in a well-lit office lined with bookcases and a map of Russia.

‘I sent for you because things are going badly at Novorossiisk,’ said Lenin. ‘The plan to scuttle the Black Sea Fleet is meeting with a lot of resistance from a section of the crews and from all the White-Guard-minded officers. […] It is necessary, at all costs, to scuttle the fleet: otherwise, it will fall into the hands of the Germans.’

Their conversation would have been incomprehensible to themselves just two or three months earlier. To destroy their own fleet would have seemed like madness. But things had changed radically in a short time.

Raskolnikov writes: ‘Vladimir Ilyich got to his feet and, sticking both his thumbs under the armpits of his waistcoat, went up to the map on the wall. I followed him.’

‘You must leave today for Novorossiisk,’ Lenin continued. ‘Be certain to take with you a couple of carriages manned by sailors, with a machine-gun. Between Kozlov and Tsaritsyn there is a dangerous situation. The Don Cossacks have cut the railway line. They’ve taken Aleksikovo. . .’

You will recall that barely six weeks before, Lenin had declared the civil war over. But now the Don Cossacks were in revolt again.

‘And on the Volga there’s a regular Vendée,’ added Lenin. ‘I know the Volga countryside well. There are some tough kulaks there.’

Lenin had just referred to the two fronts that had opened up in May 1918: the south and the east. Next week we’re going to look at the eastern front, the Vendée (revolt) on the Volga. This week we’re going to look at the south, where the Cossacks and the Volunteer Army had risen from the ashes.

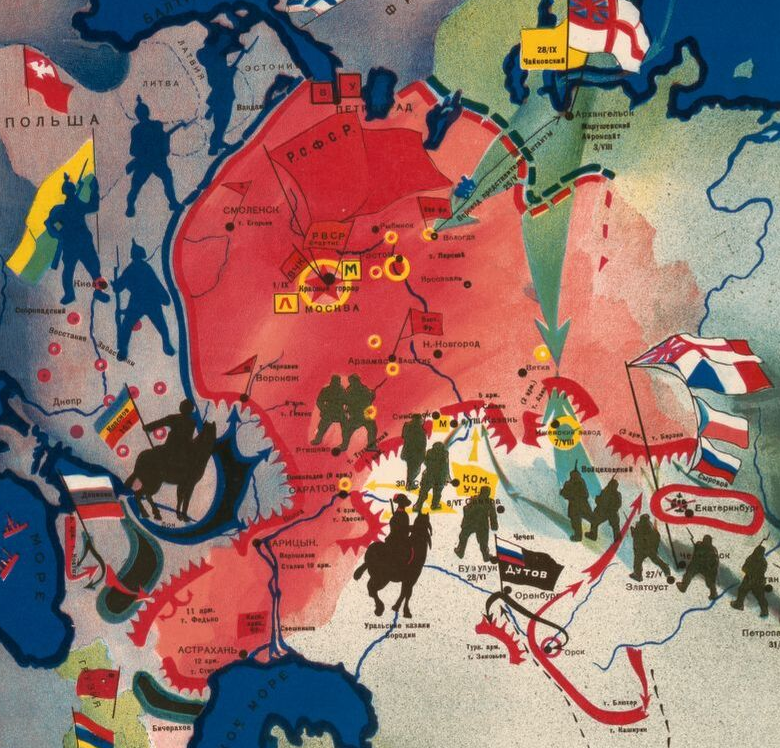

See how dramatically the territory of the Soviets has shrunk and how the southern front is a long, awkward, vulnerable shape. If you zoom in on the Black Sea coast you can see a red arrow that shows the line of march of the Taman Red Army (protagonists of The Iron Flood).

Finally, see if you can spot the killing of the royal family, shown by a symbol on the map. It occurred around this time at Ekaterinburg in the Ural mountains.

*

Raskolnikov set out from Kazan station that evening. The sunshine had given way to rain and the station smelled of wet clothes and cheap tobacco. The fresh evening air contended with the fumes from the locomotive.

Next morning he awoke on a carriage rolling through the warzone of South Russia. It was a struggle of horses and railways, and the frontlines shifted every day. Rumours of battles agitated him at every stop. There were delays; at the next station he might find a battle raging, or Whites ready to shoot him. And every hour’s delay might result in the Black Sea Fleet being handed over to the Germans.

How had this situation come about?

The Bolsheviks had come to power promising to end the war. That meant signing a treaty with Germany. But the German and Austrian governments had demanded the most humiliating concessions. In the first few months of 1918 debates had raged both within the Bolshevik Party and between the various parties of the Soviet over whether to accept these terms. Finally the German government forced the point by going on the offensive. The Red Guards were no match for the advancing German forces. The only way to stop them was to accept even worse terms. The Soviet government signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk on March 3rd, which in essence ceded the Baltic States, Poland and Ukraine to the German Empire. It was a gamble, based entirely on the hope that a workers’ revolution in Germany would render the treaty null and void.

In the meantime, there was hell to pay.

The strength of the German armies combined with the weakness of the fledgling Red Army meant that the Germans might seize any pretext to grab more territory, even to crush the revolution. The situation was so serious that Lenin had a contingency plan for the Soviet government to abandon the big cities and hold out in the Ural Mountains and the Kuznets Basin.

Three months after the signing of the Brest-Litovsk Treaty, the peace was being violated by all parties without matters yet escalating to all-out war. Now the German government was demanding that Russia’s Black Sea Fleet be handed over to them. They were in a position to seize it anyway. Moscow was determined to defy this order and sink the fleet instead. But the sailors and officers were refusing to carry out this command. That’s where Raskolnikov came in.

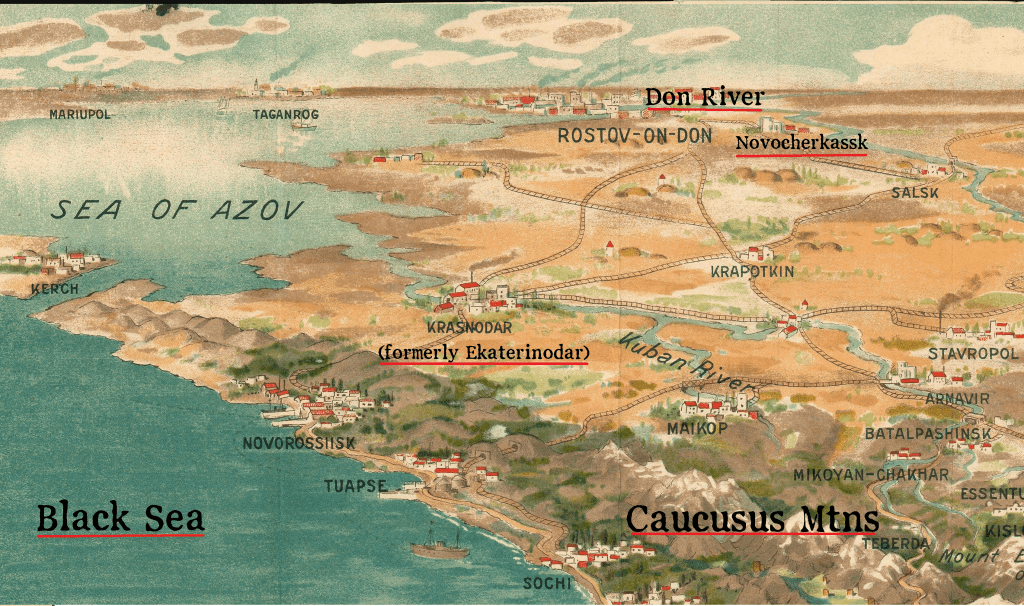

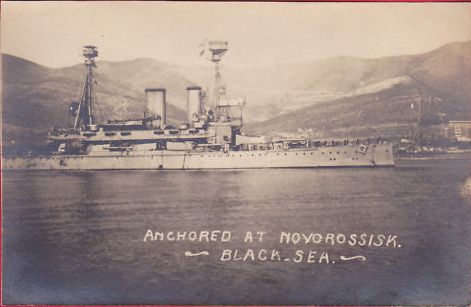

Raskolnikov made it through the war-torn Don and Kuban lands in one piece. Along the way he passed through Ekaterinodar, where Kornilov had been killed two months earlier. Now it was under siege once again. He arrived at the port of Novorossiisk at long last, taking in the view of the sunlit harbour full of destroyers and dreadnoughts.

On decks and on the shore a fierce debate was raging over whether to obey Moscow’s order.

Raskolnikov addressed a group of sailors: ‘In order that the fleet may not fall into the hands of German imperialism and may not become a weapon of counterrevolution, we must scuttle it today.’

A young sailor demanded: ‘But why can’t we put up a fight, seeing that we have such splendid ships and such long-range guns?’

The young sailor knew well that such a fight would mean certain death. This did not deter him.

As well as those who wanted to go out in a blaze of glory, there was a hidden agenda, especially among the officers. Many of them wanted to hand the fleet over to the Germans, in the hope that it would then be used against the Bolsheviks.

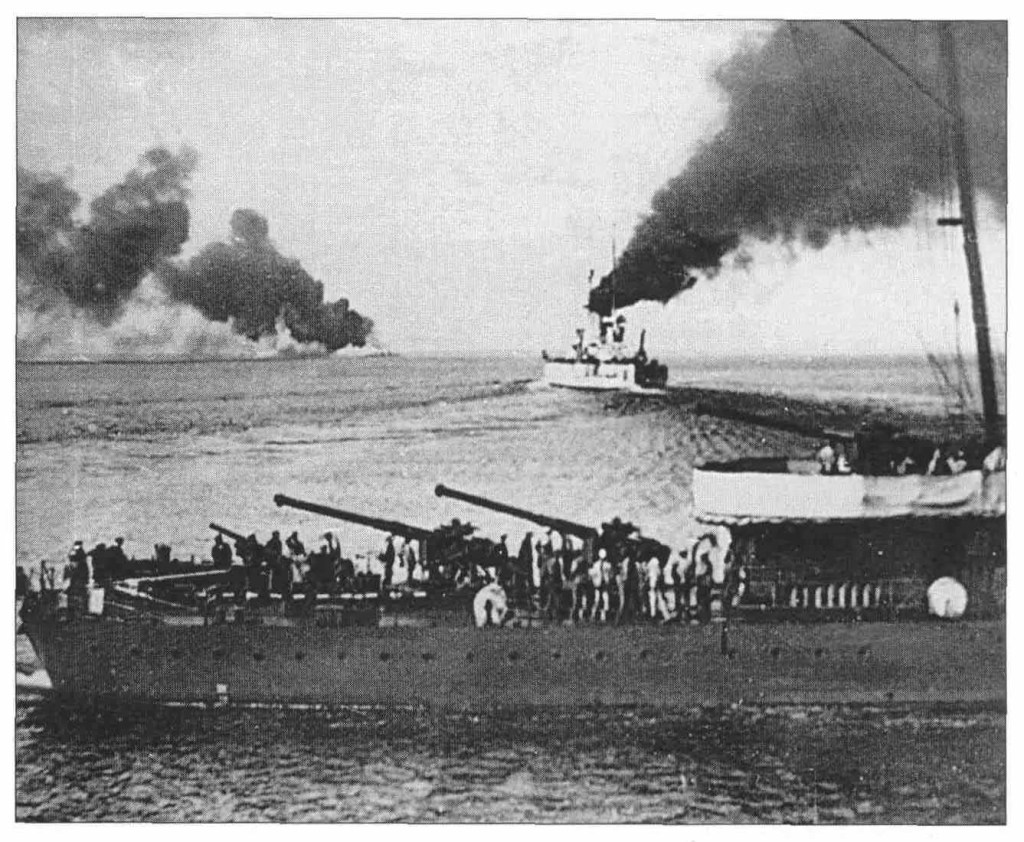

But after long debates, Raskolnikov convinced the sailors to destroy their own fleet. It was a bitter victory. If you have ever wondered what it looks like when a massive war ship is blown up and sunk, you are about to find out. Here is Raskolnikov’s description of the death of a dreadnought named Free Russia.

When the smoke dispersed, the vessel was unrecognisable: the thick armour covering her sides had been torn off in several places, and huge holes, with twisted leaves of iron and steel, gaped like lacerated wounds. […] the ship slowly heeled over to starboard. Then she began to turn upside down, with a deafening clang and roar. The steam-launches and lifeboats fell, smashed, rolled across the deck and, like so many nutshells dropped off the high ship’s side into the water. The heavy round turrets, with their three 12-inch guns, broke from the deck and slid, making a frightful din, across the smooth wooden planking, sweeping away everything in their path and at last, with a deafening splash, fell into the sea, throwing up a gigantic column of water, like a waterspout. In a few moments the ship had turned right over. Lifting in the air her ugly keel, all covered with green slime, seaweed and mussels, she still floated for another half-hour on the grey-green water, like a dead whale. […] the oblong, misshapen floating object shrank in size and at last, with a gurgling and a bubbling, was hidden beneath the waves, dragging with it into the deep great clouds of foam, and forming a deep, engulfing crater amid a violently seething whirlpool.

[…] the sailors, tense-faced and silent, as though at a funeral, bared their heads. Broken sighs and suppressed sobs could be heard.[i]

The Russian Revolution had secured peace at a terrible price. The dreadnought Free Russia was the least of it. In this and in future posts we’re going to see the consequences playing out.

THE DON COSSACK REVOLT

We saw in Part 2 how many of the Cossacks went over to the Reds. Ataman Kaledin shot himself. 18,000 Red Guards held Ekaterinodar, killed General Kornilov, and threw the Volunteer Army back out onto the steppe.

For a few weeks there were Soviet governments on both the Don and Kuban. The Don Soviet Republic had a president, Podtelkov, who was both a Cossack and a member of the Socialist Revolutionary party. But under the surface, things were changing. Most Cossacks never warmed to the Soviet government. They saw it as a government of the ‘aliens’ – their poor, despised tenants – and of the mouzhiks and khokols (insulting terms, respectively, for peasants and Ukrainians). The former frontline soldiers who had supported the Reds now settled back into village and family life, and many fell back under the influence of their elders.

In April the German forces advanced through Ukraine. The Red Guards made a stand in the Donbass. In a moment that was later celebrated in paintings and novels, Kliment Voroshilov led the courageous defence of a bridge, allowing many to escape capture or death.

The survivors fled east on a long march to Tsaritsyn on the Volga. The Don Cossacks must have watched these events with keen interest; the Donbass was in German hands, and its Red Guards were out of the picture.

More immediately, thousands of ill-disciplined and armed soldiers wearing red armbands were now streaming across Don Cossack lands. Some looted, killed perceived enemies, or assaulted women. Down in the Kuban region there was a similar crisis with soldiers returning from the Turkish front. The same Cossacks who had shunned Kaledin earlier in the year now took up arms against these intruders.

On May 8th the Germans took Rostov-on-Don; two days earlier, right-wing Don Cossacks had already risen up and seized Novocherkassk. On May 11th Podtelkov was captured on an expedition. They hanged him and shot the seventy-plus Cossacks who were with him. From there, the revolt snowballed.

The victories of the Red Guards were undone at a stroke. In April it had seemed that Civil War was over. But by mid-June the Don Cossacks had seized a vast territory and mustered an army of 40,000, with 56 artillery pieces. The resistance of the Reds was feeble; they were deprived of their base in the Donbass and distracted by the Volga revolt and the German threat.

BACK IN THE SADDLE

In earlier episodes we saw how the Volunteer Army was formed in the Cossack lands from officers who were determined to stop the revolution.

At the start of May 1918 the Volunteer Army was becalmed in the Kuban Country to the south. In February they had broken with the Don Cossacks and gone out on the Ice March; in April they had been defeated at Ekaterinodar. Now their leader Kornilov was dead and they were encircled in the wilderness.

The German advance and the Don Cossack uprising changed the situation utterly. The Germans and the Cossacks now held all the north-south railways, forming a great wall protecting the Volunteer Army from the revolutionary power that resided in Moscow.

The Volunteers at this point numbered just 9,000. The original 3-4,000 had been bolstered first by Kuban Cossacks and second by General Drozhdovtskii and his troops, who had marched all the way from Romania. We have noted the extraordinary number of generals that were in this small army; but these generals were not afraid of combat or hardship, and they dropped like flies (Markov, Drozhdovskii, Alexeev, and of course Kornilov). General Anton Denikin, bald-headed and white-bearded, the author of the memoirs we quoted in Episode 2, succeeded Kornilov as leader. Under Denikin, the Volunteers exploited the new situation.

Although the Kuban was now cut off from Moscow, the Volunteer Army still faced an enemy numbering 80-100,000 – the two Red Armies of the Caucasus and the Taman Red Army. Denikin was outnumbered ten to one. But these early ‘Red Armies’ were in fact loose coagulations of ‘detachments,’ undisciplined and untrained. Their only link to Red territory was by the Caspian Sea. Later, when ice made the sea impassable, their lifeline was a long camel train through wilderness. They were connected to Moscow by a long, thin line, via Astrakhan and then Tsaritsyn – an outpost of an outpost of an outpost. Bands of Terek Cossacks and guerrillas from Dagestan operated in their rear. Typhus raged in the ranks. And just across the Caucasus Mountains were the Turks, the British, the French, Menshevik Georgia and the forces of various nationalist parties.

And now the Kuban Cossacks rose up against the Soviet power, and flooded into the Volunteer Army. Generals who had been commanding platoons soon had companies, regiments and divisions under them again. A massacre of ‘aliens’ and ‘Bolsheviks’ began. This massacre is recorded in the novel The Iron Flood by Alexander Serafimovich.[ii] The ‘aliens’ were like survivors of a sudden apocalypse stricken with terror at the pace and fury of the revolt, as seen in this reputedly accurate account:

Slavyanskaya village has revolted, and so too have Poltavskaya, Petrovskaya and Stiblievskaya villages. They have built gallows in the squares before the churches, and they hang everybody they can catch. Cadets have come to Slavyanskaya village, stabbing, shooting, hanging, drowning men in the Kuban […] They’ve run amuck. All of Kuban is in flames. They torture those of us who are in the army, hang us on trees. Some of our detachments are fighting their way through to Ekaterinodar, or to Rostov, but they are all hacked down by Cossack swords…’[iii]

The Volunteer Army grew to at least 35,000 by September. A long and brutal struggle began. The Reds were usually on the defensive and unable to bring their numbers to bear. Still they fought hard.

The courage of these early Red formations was extraordinary. They fought for Soviet power even though it seemed they were on a sinking ship. They were poor people, each revolting against a lifetime of humiliation and toil, fighting for a better world. They had gone too far now to go back. They had to fight on through or die.

WHITE VICTORY IN THE SOUTH

Because of the numbers and dogged resistance of the Reds, the Volunteers and Kuban Cossacks were stuck fighting them for the second half of 1918 and into 1919. The rest of Season One will deal with events from May to the end of 1918 in other parts of Russia. The reader should bear in mind that this struggle at the feet of the Caucasus Mountains was grinding on relentlessly in the distance. By the time this bitter struggle finally came to an end, most White units had suffered at least 50% casualties. One cavalry unit had suffered 100%.

In a series of terrible battles Denikin and his Volunteers seized town after town. In August they seized Ekaterinodar. What was left of the Red Kuban government fled to Piatigorsk. In the autumn Novorossiisk, the bed of its harbour still strewn with the corpses of dreadnoughts and destroyers, fell to the White Guards.

In January-February 1919 a cavalry unit – the same one that suffered 100% casualties over the course of the campaign – broke through the Red lines. After that, the White forces overran the Caucasus pocket so quickly that many of them caught typhus from the Reds.

Not a whole Red Army but a whole Red Army Group was destroyed: the two vast Caucasus armies, and the smaller but brilliant Taman army – in all, 100,000-150,000 soldiers. The Whites took 50,000 prisoners, 150 artillery pieces, 350 machine-guns. Fewer than one in ten of the Reds escaped. They crossed steppe and desert in winter to Astrakhan on the Caspian Sea, where commissars traded recriminations over the catastrophe.[iv]

I have jumped ahead of the main narrative. Let’s return to the summer of 1918.

DENIKIN’S KUBAN STATE

General Anton Denikin had been campaigning for a military dictatorship since the summer of 1917. Now, probably to his great surprise, he found himself in charge of one. The Volunteer Army set up a militarised state in the Kuban Cossack lands. They were just to the south of the new Don Cossack Republic, though relations were not neighbourly.

Denikin’s politics were close to Kornilov’s. After the Reds were defeated, he promised, elections to a National Assembly would be held and the military dictatorship would end.

For Denikin there could be no question of restoring power to the Constituent Assembly. It ‘arose in the days of popular insanity, was half made up of anarchist elements.’ My impression is that Denikin and the officers would not have considered any election legitimate unless a knout-wielding Cossack glowered over every ballot box.

Denikin did not like to admit he was a reactionary. On occasion he spoke of self-determination, but he spoke far more often of ‘Russia, One and Indivisible.’[v] Jonathan Smele makes the fair point that Denikin and Kolchak (Kolchak was another key White leader) were ‘far from the clichéd caricatures of pince-nez-adorned, sadistic fops’ of Red propaganda. Kolchak, Denikin, Kornilov and Alexeev were not aristocrats. Denikin’s father had been born a serf.

But a few lines later Smele concedes that the camps of these generals were heavily-populated with nobles and the wealthy (and many of them, in accordance with the values of Tsarist military discipline, would absolutely have been sadistic fops wearing pince-nez). As stated in Part One, a fifth of the Volunteer Army’s personnel came from noble families. British officers, invited to a great banquet in Denikin’s territory, were embarrassed when the orchestra began to play ‘God Save the Tsar.’ The request had come from a member of the royal family who was present.[vi]

The non-military sphere of Denikin’s government was limited – war was ‘not the right time for solving social problems’ – but it was dominated by members of the Constitutional Democrats, a party with a wealthy support base. Perhaps Denikin was chosen as leader partly because of his humble background and the sympathetic, ‘democratic’ face he could show to the world. But as we saw in Part 2, he was as determined a counter-revolutionary as any officer in Russia.

The Volunteer Army was composed of men for whom war was a vocation. They expressed this in an elaborate system of uniforms and badges. The ‘colourful’ regiments were named after dead generals and wore distinctive uniforms. The Kornilovtsii, for example, wore black tunics with red caps, and wore a shoulder badge with a skull, crossed bones and crossed swords. Veterans of the Ice March wore a badge with a crown of thorns on it.[vii]

In 1919 Denikin’s army would go on a huge offensive against Moscow. By then it had grown so much that the Kornilovtsii had turned from a regiment into an entire division. The terrible struggles of 1919 will have to wait until Season Two of this series. For now, the reader only has to keep in mind that for the rest of 1918 and into the early part of the following year, Denikin and his army were engaged in a merciless and brutal struggle in the South.

KALEDIN TO KRASNOV

Can a single individual change the course of history?

In the years before the revolution the socialists of Russia had meditated on just this question. ‘The role of the individual in history’ (1898) was a pamphlet by George Plekhanov, a founder of Russian Marxism. This text argued that leaders and supposed ‘great men’ were in fact mere conduits for the great impersonal forces of history.

Plekhanov himself had, by 1918, long since broken with his past politics and was firmly on the right of the Menshevik party. He cursed the Bolsheviks and the revolution as ‘a revolting mixture of Utopian idealists, imbeciles, traitors and anarchist provocateurs.’ ‘We must not only crush this vermin, but drown it in blood.’ ‘If a rising does not come spontaneously it must be provoked.’[viii]

Meanwhile a Bolshevik artillery piece in Ekaterinodar had proved the point he had argued in his pamphlet twenty years before. The shell that killed Kornilov showed the limits of the role of the individual in history. The movement Kornilov led survived in spite of his death, produced a new leader in the form of Denikin, and carried on from strength to strength.

The same thing happened in the Don Cossack country. Kaledin had committed suicide in February. By May his supporters had returned to power, and they produced a new leader in the form of General Piotr Krasnov.

This Krasnov had tried to seize Petrograd in November 1917 but was defeated and captured. These were the magnanimous early days of the revolution, so he was not put up against a wall and shot, or even locked up. He was released on his word of honour that he would never again raise a hand against the Soviet power. July found Krasnov leading an army of 40,000 Don Cossacks against the Soviet power.

Krasnov did not just break his word to the Reds. He betrayed the cause he had served during the World War. During the war against Germany he had commanded a brigade, then a division, then a corps. I don’t know how many lives he spent on the frontlines in the struggle against the Kaiser. Now his Don Cossack Republic owed its existence to the German army, received arms and aid from it, and paid it back with loyalty. Krasnov even became pen-pals with the Kaiser.

Denikin remarked, ‘The Don Host is a prostitute, selling herself off to whoever will pay.’

The Don Cossack officer Denisov retorted: ‘If the Don Host is a prostitute, then the Volunteer Army is a pimp living off her earnings.’

It was easy for those posh officers to act all high-and-mighty, but they owed their survival to the German intervention. The Volunteer Army even got weapons from Germany, via the Don Cossacks.

The Cossacks knew that the Volunteer Army saw them as petty and provincial, as diminutive Kazachki. For their part, Denisov spoke for the Don Cossacks when he called the Volunteer Army ‘travelling musicians.’ This obscure remark seems to mean that the Volunteers were not an army of the people, rooted in the soil as the Cossacks were, but an army of the intelligentsia and upper classes.

But for now each of these forces was busy in its own backyard, and there was no cause for them to clash. While the Volunteers were grinding the hundred thousand Reds of the Caucasus to dust, the Don Cossacks were on the offensive eastward to Tsaritsyn, and northward to Voronezh.

The Reds could only watch from a great distance as the Red Armies of the Caucasus went down fighting. On the Voronezh and Tsaritsyn fronts, they could only react, not take the initiative. They were distracted by the fighting on the Volga, by the German threat, and finally by a revolt at the very heart of Soviet power. These events, respectively, will be the focus of the next two parts in this series.

Audio credits: Music from Sergei Prokofiev, Alexander Nevsky

Clip from Blackadder Goes Forth, e3 ‘Major Star’, dir Richard Boden

Opening clip from Tsar to Lenin, 1937, dir. Herman Axelbank

[i] Raskolnikov, FF. Tales of Sub-Lieutenant Ilyin, 1934 (New Park, 1982), ‘The Fate of the Black Sea Fleet’ https://www.marxists.org/history/ussr/government/red-army/1918/raskolnikov/ilyin/index.htm

[ii] Mawdsley, Evan. The Russian Civil War, 1987 (2017), Birlinn Limited, 129

[iii] Serafimovich, Aleksander. The Iron Flood, 3rd Edition. Hyperion Press, Westport, Connecticut. 1973 (1924), p 13

[iv] These commissars included Shlyapnikov, whom we met in Part One. He was based at Astrakhan and held responsible for the disaster. He replied that the Soviet government had neglected the Red Army Group in the Caucasus, which was true.

[v] Mawdsley, p 132

[vi] Smele, Jonathan. The ‘Russian’ Civil Wars, Hurst & Company, 2015, pp 106, 302

[vii] Khvostov, Mikhail. Illustrated by Karachtchouk, Andrei. The Russian Civil War (2) White Armies, Osprey 1997 (2007), pp 12, 14-15

[viii] It has become routine to call Plekhanov and his party ‘moderate socialists’ even though they were as violent as any other force in the Civil War. Serge, Victor. Year One of the Russian Revolution, p 98

7 thoughts on “04: Cossack Revolt in the South”