‘The revolution is a big and serious machine. What today is a difference of opinion, a perplexity, will tomorrow be transformed into a civil war.’

Trotsky, July 1918

Two Chekists

Moscow, on the afternoon of July 6th 1918. Two Chekists are approaching the German legation on Denezhny Lane. One, Yakov Blumkin, carries a briefcase in which a Browning pistol is hidden. Both carry hand grenades.

A Chekist is a member of the security organ of the Soviet, the Special Commission known by its acronym, Cheka. In later years it will develop into the GPU, the NKVD, the KGB: names synonymous with the brutal enforcement of the one-party state. But in summer 1918 the Cheka is only a few months old, and does not have that reputation. These two Chekists, Blumkin and his companion Andreyev, are not even members of the ruling Communist Party. Like many Chekists, they are Left Socialist Revolutionaries.

It would be difficult to mistake Blumkin for a Bolshevik. Bolsheviks prefer tea to alcohol, but Blumkin is known to get drunk in cafés listening to the poetry of revolutionary and reactionary writers with equal rapture. He is ‘poised and virile… his face solid and smooth-shaven,’ with a ‘haughty profile.’[i] He is not above, on occasion, drunkenly brandishing a pistol in public.

Blumkin and Andreyev show their credentials at the door of the German legation. Their letters of introduction bear the signature of the Cheka head, Felix Dzerzhinsky. They ask to see the German ambassador, Count Wilhem von Mirbach-Harff. Count Mirbach’s son, a lieutenant in the German army, is missing, and Blumkin and Andreyev claim to have news of him. But their letter of introduction is phony, as is their stated reason for being here. They have come here to kill a man and to start a war.

Count Mirbach meets with the two Chekists in a downstairs room. An interpreter and a member of the legation staff are present.

Blumkin opens his briefcase, saying ‘Look here, I have…’

He pulls out the Browning pistol and opens fire at the German ambassador.

The Terrorist Tradition

When Yakov Blumkin drew that pistol, he was acting in a verable tradition of Russian terrorism.

Throughout the 19th Century the Russian liberals, known as Populists, tried to shake the Tsarist autocracy using the weapon of assassination. The older brother of Lenin and the older brother of the Polish nationalist leader Józef Pilsudski were both hanged for their roles in the same assassination plot. Maria Spiridonova, as mentioned in Chapter 1, killed a police chief in 1906 and suffered vicious treatment in prison. Her party, the SRs, descended directly from the terrorist tradition.

From the 1880s a new revolutionary tradition grew up in the Russian Empire, one that rejected this tactic of ‘individual terror.’ The Marxists believed that it was necessary to destroy the system itself, not individual human figureheads who could be easily replaced.

The Bolshevik Party came from this tradition, rejecting terror. They were oriented to the working class and to its open, democratic methods of struggle, such as strikes and mass demonstrations, though since they operated under a police state they were often confined to the illegal underground.

Meanwhile, as we have seen, the Right SRs had grown closer to the Constitutional Democrats, while the Left SRs appeared to move closer to the Bolsheviks. But neither Left nor Right SRs ever gave up on the bullet or the bomb. ‘Individual terrorism’ would rear its head in 1918, in events that set the course of the Russian Civil War.

The split between the Bolsheviks and the Left SRs

That morning, as Blumkin and Andreyev went to kill the German ambassador, Soviet Russia was still a multi-party Soviet democracy.

In workplaces, in the fleets, in the Red Guard units, in the Cheka and in the Soviet, Bolsheviks and Left SRs worked side-by-side. As we have seen, in January the Bolsheviks were pleased to vote for Maria Spiridonova, now leader of the Left SRs, as their candidate for president of the Constituent Assembly.

The Bolsheviks and the Left SRs had even formed a coalition Soviet government in December 1917, a coalition which lasted for four months. There was mutual admiration as well as mutual distrust. The Bolsheviks had authority because they had made the October Revolution. The Left SRs had a far higher profile among the rural toilers. But to the Left SRs the Bolsheviks seemed to embody a contradictory mixture of dogmatism and unscrupulousness. For their part, the Bolsheviks saw the Left SRs as muddleheads, terrible at picking their battles. They were always wavering on the most fundamental principles, but proving stubborn on secondary matters.

The slogan ‘Peace, Bread and Land’ united the Bolsheviks and the Left SRs. The land question was the basis of the alliance.

In power, the Bolsheviks delivered immediately on the land question, passing a decree that took over the land of the former nobility and the church and gave it to tens of millions of peasants. This was a great victory for the peasants: over the next few years the number of farming households rose from 18 to 24 million and the average size of a farm increased. Young couples escaped from overcrowded multi-generational households to start their own farms and homes. In late 1917 and well into 1918 the mass of peasants supported the revolution with enthusiasm. The coalition between the worker-based Bolsheviks and the Left SRs, who had a more rural support base, reflected this fact.

The rupture came over the other two-thirds of the slogan: peace and bread.

Peace

The Brest-Litovsk Treaty making peace with Germany was deeply controversial among the Bolsheviks. But the Left SRs were completely opposed to this ‘obscene peace.’ They were determined to fight German imperialism to the end, even if they were driven out of the cities and up into the Ural Mountains. In March 1918 they walked out of the Soviet coalition government over this question. After walking out they still held many high positions in the Soviet, the Red Army and the Cheka. It was a one-party government (like most British and all US administrations) but by no means a one-party state.

It’s important to appreciate the full and terrible cost of the Brest-Litovsk peace. Finland gained independence from Russia thanks to the Revolution. In free Finland as in Russia, socialists took power with the mass support of workers. But a Finnish White Army, aided by German volunteers and weapons, rebelled, seized power and crushed the revolution. It was all over before May 1918. Tens of thousands of Red supporters were shot. More were starved to death in prison camps. The scale of the bloodshed would have been terrible anywhere, but in a country of only three million people it was staggering. By way of comparison, years of revolution and civil war in Ireland, a country with a population of similar size, claimed the lives of around six thousand people.[ii] Counter-revolution in Finland exceeded that toll many times over in just a few months. The Reds longed to intervene and help their Finnish comrades, but their hands were tied by the peace treaty. Workers in Russia could only stand by in horror while massacres unfolded just a couple of railway stops from Red Petrograd.

They knew that if the White Guards won in Russia, they would suffer the same fate.

Another consequence of the treaty was that the German army occupied Ukraine and the Baltic States. They began seizing food and executing people. Not just in Finland but in Ukraine, Latvia and Estonia, revolutions were being crushed right on the doorstep of Soviet Russia. Thanks to the treaty there was nothing to be done.

Bread

Even after they resigned from government, the Left SRs still cooperated with the Bolsheviks. But the gulf between the two parties widened further over the question of bread.

‘Suspend the offensive against capital,’ was Lenin’s slogan in early 1918. In the socio-economic as in the military sphere, he judged that the country needed a breathing space. Early on, the Communist Party favoured slow and measured changes in the economy: the nationalisation of the banks and major industries, and gradual intrusions into the rest of the economy. The ‘Left Communists’ argued for faster nationalisation and more state control of markets, but they were soundly defeated in an internal party debate.

But by early summer, the Communist Party as a whole had been forced, by war and by a campaign of sabotage in the factories and mines, to resort to the measures proposed by the Left Communists. According to the Communist Rykov, ‘Nationalisation was a reprisal, not an economic policy.’[iii]

The food crisis which had begun in 1914 was still getting worse. The revolt of White armies led to a breakdown in transport, and the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk cut off Russia from food-producing areas. But the most significant cause of the food crisis was the breakdown of industrial production. There was no shortage of food in the countryside, but the peasants would not trade it for paper money when there was no production and so nothing to buy.

Therefore, according to the dictates of the market, the cities would starve to death. But the Communists were not inclined to accept the dictates of the market or the prospect of their supporters starving to death.

By summer 1918 food detachments were descending on the villages, seizing any surplus grain to feed the cities. There were important continuities between this ‘food dictatorship’ and the food policies of the Provisional Government and even those of the Tsar adopted since 1914.[iv] But this went further. Peasants, especially the wealthier layers, saw the food detachments as an attack on their right to trade. The reaction was furious. Of 70,000 workers who joined food detachments, 7,000 of them were killed by angry peasants in 1918 alone. Kulaks would wait in ambush, sawn-off rifles hidden in the folds of their shirts. Communists would be found dead, their stomachs slit open and stuffed with grain.

The Left SRs’ desire to restart the war with Germany was not popular in the countryside. But they spoke for many peasants when they condemned the food dictatorship. The Bolsheviks, meanwhile, as if to mark the end of the honeymoon, had moved the seat of government from Petrograd to Moscow and had changed their name officially from the Social-Democratic and Labour Party (Bolshevik) to the Communist Party. People who did not follow the news carefully – and it was difficult, in those days, to follow the news – would remark that they supported the Bolsheviks, but hated these new Communists; or would claim that the Bolsheviks were led by Trotsky and the Communists by Lenin, or vice versa, and that they were fighting one another.

July 1918

The conflict came to a head at the beginning of July.

This was a moment of dire military crisis for the Soviets. To the east, the Czechs had revolted and, along with the Whites, were seizing town after town. To the west, the Germans occupied a vast stretch of territory. To the south, the Cossacks and the Volunteers were making steady gains. To the north, British forces landed at Murmansk on July 1st. On the 2nd and 3rd, key cities fell to the Czechs. Throughout these days Count Mirbach, the German ambassador, would sit in the Bolshoi Theatre observing sessions of the Soviet and would relay ever-escalating demands from Berlin. Meanwhile the Left SRs were active on the western border, shooting and bombing and agitating, trying to trigger a war between Germany and the Soviets.

These were the political developments that placed Blumkin and Andreyev in the legation on the afternoon of July 6th, face-to-face with Count Mirbach, the hated representative of German imperialism. By shooting him, they believed they would trigger a response from Germany, beginning a spiral into war.

*

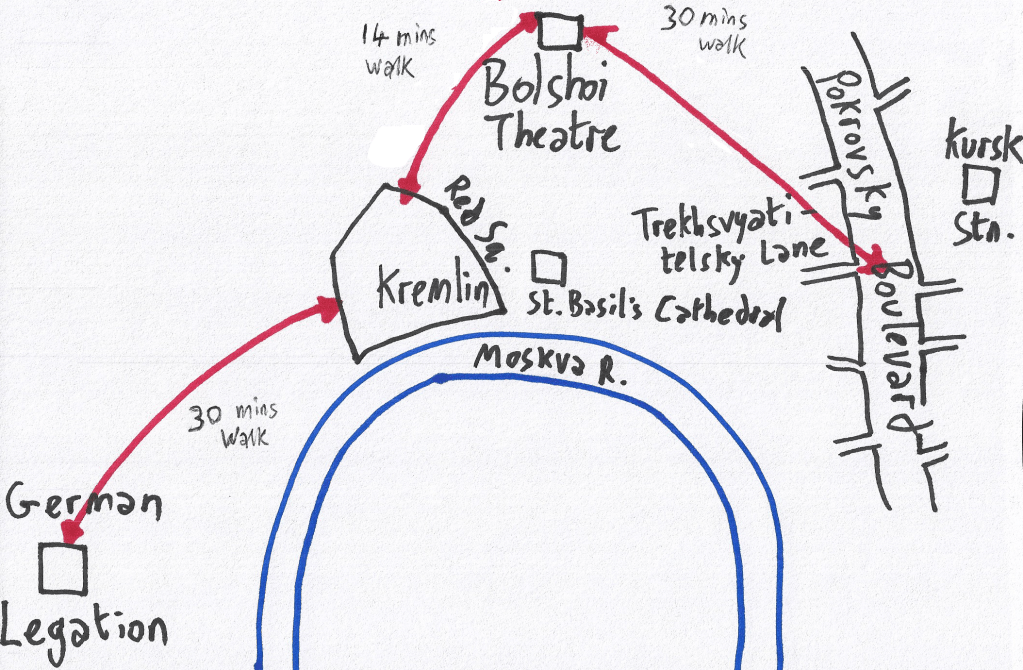

Blumkin pulls the trigger. Count Mirbach flees into another room while the two members of staff dive under the table. Andreyev throws a grenade after Mirbach, but misses. Blumkin darts forward, grabs the grenade before it can explode, and throws it again. It’s on target. The explosion kills the Count and throws Blumkin out the window and into the street. He and Andreyev flee in a getaway car to the Cheka Barracks on Pokrovsky Boulevard. This barracks is controlled by a Cheka unit under a Left SR named Popov. Popov is in on the conspiracy, and the barracks is a safe house for the assassins.[v]

*

Word of the assassination spreads quickly. At first everyone assumes that the murder is the work of White Guards or Anarchists. Felix Dzerzhinsky, leader of the Cheka, takes on the murder investigation personally.

Stories about Sherlock Holmes are immensely popular in Russia at this time. Dzerzhinsky inspects the crime scene personally in a moment reminiscent of Arthur Conan Doyle. But the Polish Communist’s severe face and sunken toothless mouth, a souvenir of torture and trauma in Tsarist prisons, don’t really fit.

He is quick to find the forged credentials at the murder scene bearing his own signature. Who would have access to such credentials? Not the Anarchists or the White Guards. For the first time, he begins to suspect Left SR involvement. He goes straight to the Pokrovsky Boulevard, to ask his Chekist subordinate Popov to clarify the situation.

He probably assumes it is safe. The initial reaction of Trotsky was to say, ‘It must be individual madmen and criminals who have committed this terroristic act, for it is impossible that the Central Committee of the Left SR Party can be mixed up in it.’ Dzerzhinsky’s attitude is probably similar at this point.

He and his personnel arrive at the Pokrovsky Barracks and begin to search the place. But before they can find the assassins, they open a door to find the Central Committee of the Left SR party in session.

If Dzerzhinsky is shocked he doesn’t let it show. He demands that they surrender the assassins.

The Left SR leaders respond that they take full responsibility for the killing of Mirbach.

Dzerzhinsky, though far outnumbered, declares the lot of them under arrest. He is immediately disarmed and captured.

*

Thirty minutes’ walk away the Fifth Congress of the Soviets is in session in the Bolshoi Theatre. Word has not yet arrived about the murder of Mirbach. It is a fractious meeting. Roughly two thirds of the delegates are Bolsheviks, one third Left SRs, plus anarchists and others. Of the Left SRs, one third are workers, one third peasants and one third intelligentsia.

The delegates have been debating for hours. The Commissar for War Trotsky condemns the Left SRs for agitating on the frontlines, for trying to kill German soldiers and trigger a conflict.

The delegates heckle him, branding him with the name of the disgraced leader of the Provisional Government: ‘Kerensky!’

A Left SR speaker lays out their position: it is impossible ‘to tolerate the German marauders and hangmen, to be accomplices of those villains and plunderers.’[vii]

It is Maria Spiridonova who, around 4pm, arrives at the Bolshoi Theatre bearing the news that Mirbach has been murdered. Spiridonova was in on the plan, but most of the Left SR delegates in the Bolshoi are blindsided. Meanwhile one or two thousand Left SR fighters have gathered around Trekhsvyatitelsky Lane. They attempt to seize key buildings, and they arrest Communist and non-party Red Guards and Chekists.

The Communists immediately lock down the Bolshoi and imprison the Left SR delegates.

The Soviet government ministers meet and, Trotsky will later write, ‘from a building in the Kremlin, we saw shells – fortunately, only a few – landing in the courtyard.’

During the night the Left SRs seize the post office and send out a telegram to the provinces:

Count Mirbach, torturer of the Russian toilers, friend and favorite of [Kaiser] Wilhelm, has been killed by the avenging hand of a revolutionary in accordance with the resolution of the Central Committee of the Left SR Party. German spies and traitors demand the death of the Left SRs. The ruling group of Bolsheviks, fearing undesirable consequences for themselves, continue to obey the orders of German hangmen.[viii]

An order to the telegraph workers, signed by an SR Maximalist, goes further: ‘…all cables with Lenin’s, Trotsky’s and Sverdlov’s signatures as well as all cables from counterrevolutionaries which are dangerous to Soviet power in general and the Left SR Party currently in power in particular are to be withheld.’

Maybe this order comes from the Left SR leaders, or maybe the SR Maximalist who signed it is basically going rogue. Either way, word has gone out from Moscow that armed insurgents have seized key parts of the city with the intention of overthrowing the Communist government.

*

In the dead of night Vacietis, the leader of the Latvian Rifles, is summoned to the Kremlin.

‘Comrade,’ says Lenin, ‘can we hold out until morning?’

Even to the formidable Vacietis, things must look bad. The Left SR forces are considerable: their own combat units, plus 600 Chekists under the command of Popov, plus a few anarchists and Black Sea sailors. Most of the fledgling Red Army is on the front facing the German threat; whoever else can be spared is either in the east or in the south, fighting the Whites. At that moment Vacietis has only four Latvian Rifle regiments and a force of Hungarian communists, former prisoners-of-war led by Bela Kun.

*

Insurrection is dangerous. You don’t know who is going to rally to your side until after you’ve stuck your neck out. Then it’s too late to call it off; if you back down, your plans will be discovered and you’ll face the consequences anyway. Insurrections therefore often hedge themselves in a ‘defensive’ political cover. Even the October Revolution employed such cover. The Left SR uprising of July 1918 attempts to do the same. The order to the telegraph workers referring to the Left SRs as ‘currently in power’ is unusually bold. The resolution of the Left SR central committee is more cautious and more typical of its communications during the revolt:

We regard our policy as an attack on the present policy of the Soviet government, not as an attack on the Bolsheviks themselves. As it is possible that the latter may take aggressive counteraction against our party, we are determined, if necessary, to defend the position we have taken with force of arms.

In October the defensive cover deceived and demoralised the government. But in July 1918 the defensive cover deceives and demoralises the insurgents. The Left SR fighters don’t know what they’re doing. They fight without energy or initiative; after the initial gains, there are no further advances. There are high-ranking Left SR Red Army officers in the vicinity of Moscow with large forces at their command. But they do not join the revolt. Vacietis himself is not a member of the Communist Party (According to some sources he is even a Left SR).[ix]

The next morning there is heavy fighting in the central Kitai-Gorod area of Moscow. Left SR fighters are chased out of Trekhsvyatitelsky Lane and pursued to the Kursk railway station. They abandon armoured cars and weapons as they flee. The Latvians manage to get a 152mm howitzer up close to the Left SR headquarters and they open fire at point-blank range. By noon the Left SRs are defeated and Dzerzhinsky has emerged from the shell-scarred building.

Three hundred are arrested and thirteen, all Left SR members of the Cheka, are executed. One of them is a young man called Alexandrovitch, deputy head of the Cheka. Dzerzhinsky respected Alexandrovitch and is disturbed by his execution.

The poet-terrorist Blumkin, who threw the fatal grenade, has meanwhile fled to Ukraine, where he works in the guerrilla underground against the German occupation.

Muraviev

In the aftermath of the uprising the Left SR party is destroyed – but not by executions or arrests.

Trotsky describes the Left SR leaders as isolated intellectuals surrounded by a ‘yawning void’, and claims they were egged on by ‘bourgeois public opinion.’ But he also declares that ninety-eight percent of Left SRs are blameless. Any Left SR who renounces the actions of their central committee faces no sanction. Those who openly support the uprising and the murder of Mirbach are not arrested, though any employed by the Soviet state lose their jobs.

The party splits. Many join the Communist Party. Others attempt to rebuild the Left SRs as a party of legal opposition, but make little headway. Others still go underground to continue the armed struggle.

Months later the SR central committee are put on trial. Maria Spiridonova and her comrade Sablin are each sentenced to a year in prison. The other committee members are all on the run; they get three-year sentences except for the Chekist Popov, who is condemned to death. But he joins the Anarchist Nestor Makhno. From time to time as the civil war rages on such ex-Left SR groups and individuals will rise briefly to prominence in one faction or another.

*

In the days immediately after the rising, anxiety hung over the Kremlin. Colonel Muraviev, ‘effectively the commander-in-chief of the Red Army,’[x] was a Left SR. He was at Kazan on the Volga, facing the Czechs. Lenin’s worries were soothed after a friendly exchange of telegrams; Muraviev renounced his Left SR membership, and Lenin publicly declared complete confidence in him. This was the same soldier who had defended Petrograd from a Cossack onslaught in November 1917; the same officer who won the battle of Kyiv in January 1918.

But everything changed in a matter of hours. On July 9th Muraviev rose in revolt against the Bolsheviks and sailed down the Volga with a thousand soldiers, declaring himself ‘the Garibaldi of the Russian people.’ He called on the Red Army and the Czechoslovaks to join forces in a crusade against Germany. His thousand men disembarked and seized the town of Simbirsk. ‘On the night of the 10 July Communist rule on the Volga, and perhaps ultimately in all of Russia, hung by a thread.’[xi] But a young Bolshevik worker and Soviet official, a Lithuanian named Vareikis, set an ambush for Muraviev. The commander’s body was left with five bullet holes and several bayonet wounds. The revolt collapsed.

But the damage was done. Two weeks later Vareikis and his comrades were chased out of Simbirsk by a force of just 1,500 Czechs and Whites.

In the days following the Moscow rising there was a series of failed revolts in provincial towns – the work of White officers with Allied backing. The most serious was at Iaroslavl’, a town of 100,000 on the Volga and on the railway line between Moscow and Archangel’sk. The insurgents got away with their coup because the local Red regiment declared neutrality. The local Mensheviks did the same (no doubt they were embittered by a recent dispute in which the local Bolsheviks had gone to the lengths of shutting down the Soviet and arresting the Menshevik delegates [xii]).

The Allies had promised help from their base at Archangel’sk, but it did not come, and the local workers and peasants gave no aid to the Iaroslavl’ insurgents. The Red Army closed in and bombarded the town with artillery for twelve days, one of the few examples during the Civil War of such a heavy bombardment of a town. The Whites surrendered on July 20th, after which the Reds shot around 400 of them. ‘It was the first serious episode of the Terror,’ notes Victor Serge. 40,000 of the population of Iaroslavl’ were left homeless due to the destruction caused by the battle.

The Tragedy of Soviet Democracy

The Left SR uprising was a milestone in the slow death of Soviet democracy, though that was not obvious or inevitable at the time. Here we have to get ahead of ourselves to draw out the significance of what had happened.

The Communist Party had never called for a one-party state and never formally instituted one. On the contrary, the writings of Lenin and Trotsky show that the plan was for a multi-party Soviet democracy. [xiii] In the early period of the Revolution the Communists tolerated any party that did not take up arms against them, and even some that did take up arms. But after the Left SR Uprising, the Soviets were dominated by a single party. It was a one-party system de facto, not de jure. There were several causes for this.

The SRs and Mensheviks were kicked out of the higher Soviet bodies from June 1918 because they had thrown their lot in with armed counter-revolution (The SRs to a greater extent than the Mensheviks). They still operated freely in local Soviets and congresses, and later the bans were lifted. The Left SRs were never banned, but discredited by their own actions in the July uprising. ‘Bound in shallows and in miseries’ in the years after their failed insurrection, they must have cursed themselves. Instead of preserving the possibility of a multi-party Soviet system, they had risen up in arms. On top of that, they had chosen the wrong hill to die on. They might have gained some traction if they had risen up on behalf of the peasants, with a programme of opposition to Bolshevik food policy. But they rose up for the sake of the war, which the peasants did not want.

To sum up, those who supported armed counter-revolution were (sometimes) kicked out of the Soviets, and ‘loyal opposition’ groups failed to win mass support.

The Fate of Blumkin

What happened to Yakov Blumkin, the warrior-poet and assassin of Count Mirbach?

By April 1919 the Civil War was raging in its full fury, and Ukraine was a front of its own. Blumkin was arrested there by the Reds. Trotsky spoke at length with him. Maybe their interview was a fierce debate on the key questions of the Russian Revolution: peace, bread, land, freedom. Or maybe the end of the World War had narrowed the political distance between the Bolshevik and the Left SR. Whatever was said, we know that Trotsky convinced Blumkin, won him over to the Communist point of view. Not only was Blumkin amnestied, he joined the Cheka and became an intrepid Communist agent in Persia, Mongolia and elsewhere.

His former comrades in the Left SR party tried to kill him as a traitor. While he was recovering in hospital from the attempt, they tried again, throwing a grenade in the window. Blumkin repeated the trick he claimed to have pulled in the German legation in 1918: he picked up the grenade before it could detonate, and threw it back out the window.

When the tide of revolution went out and Stalinist counter-revolution took hold, Blumkin was an early victim. In 1919 he was forgiven for taking part in an armed uprising and for trying to drag Russia into a war at a time when it barely had an army. But by 1931 a lot of things had changed. Trotsky had been in exile for several years. Blumkin, while on an official trip abroad, paid his old comrade a visit. For this crime, Blumkin was arrested and executed on his return to the Soviet Union.[xiv]

I’ve used a lot of stills from the 1968 Soviet film The Sixth of July. Neither my Russian nor the automatic subtitles were good enough for me to do more than follow the general outlines of the story. But it is remarkable that they felt it necessary, as late as 1968, to erase Trotsky entirely! It’s completely crazy.

[i] This description comes from Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary. https://www.marxists.org/archive/serge/1945/memoirs/ch01a.htm

[ii] In Ireland, a country with a similar population to Finland, the struggle for independence claimed 2,850 lives (Pádraig Óg Ó Ruairc, review of The Dead Of the Irish Revolution in History Ireland, March/April 2021). The fatalities of the Irish Civil War (1922-23) add up to a similar number.

[iii] Serge, Victor. Year One of the Russian Revolution, 1930 (Haymarket, 2015)

255

[iv] Traditionally, rural society was divided into poor peasants, middle peasants and kulaks.

[v] That’s the way Blumkin told the story to Victor Serge years later. For some reason, Serge got the impression that this all happened at the dead of night, not on a summer afternoon. According to other accounts Andreyev, not Blumkin, fired the fatal shots.

[vi] The words of Trotsky, after the event, speaking of the initial reaction of himself and others. From Trotsky, How the Revolution Armed: Volume I, ‘The Revolt of the Left SRs’ https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1918/military/ch34.htm

[vii] Hafner, Lutz, ‘The Assassination of Count Mirbach and the “July Uprising” of the Left Socialist Revolutionaries in Moscow, 1918,’ The Russian Review , Jul., 1991, Vol. 50, No. 3 (Jul., 1991), pp. 324-344

[viii] Hafner

[ix] Lutz Hafner interprets the defensive posture of the Left SRs as evidence that there was, in fact, no ‘Left SR Uprising’ and that the whole thing was cynically hyped up by the Bolsheviks for their own ends. But in my reading, information in Hafner’s own article disproves this conspiracy theory.

[x] Mawdsley, Evan. The Russian Civil War, 1982 (Birlinn, 2017)

[xi] Mawdsley, 77

[xii] Smith, Russia in Revolution: An Empire in Crisis 1890 to 1928, Oxford University Press, 2017, 160

[xiii] LeBlanc, Paul. Lenin and the Revolutionary Party, Haymarket Books, 1993, 260-269.

[xiv] Deutscher, Isaac, The Prophet Outcast, Oxford University Press, 1963p 84-86

10 thoughts on “06: A Murder in Moscow”