When it was briefly mentioned on The Mindy Project, it was described as (something like) ‘That book that every guy loves for some reason.’ I read Dune at age 15. The years passed and I forgot some of the details of the story, but it held on in some remote sietch in the back of my mind, from which echoed phrases like Gom Jabbar, Muad’Dib, Kwisatz Haderach; mantras like ‘Fear is the mind-killer’ and ‘Who controls the spice controls the universe.’ The recent film captured some of that hypnotic power, and gave me an urge to visit that strange place again.

Re-reading it was a trip. Here are some things that struck me. In each case I was left wondering, ‘How does the novel get away with that?’

There is no scene of space travel in Dune. A chapter on planet Caladan ends; the next chapter begins with the characters literally unpacking their bags on planet Arrakis. The author Frank Herbert tells us that the Guild of Navigators have a monopoly on space travel, but he is not interested in exploring the technical details. He is more interested in the Guild as a political force. Therefore, unlike both of the movie versions, the space travel happens off-screen. It’s a bold move but it works. It brings focus to the story.

Dune’s rich and strange world

In the early pages we are immersed in a kind of Renaissance space feudalism. It’s all nobles having conversations in palaces; it really shouldn’t be so interesting. I don’t think space capitalism, let alone space feudalism, is plausible. There are books I’ve abandoned because there were too many nobles, too many palaces. But somehow Dune gets away with it. It confronts us with a world that runs on its own rules, and doesn’t care what we think of it. Its people are medieval in outlook, and they don’t make any effort to relate to us on our terms. Not only do these people all do drugs, drugs are at the very the centre of their society. They have slaves, they hold entire planets as fiefs and some of them have psychic powers.

In short, Herbert doesn’t try to meet us half-way. We must either dismount from the great sandworm that is this book, and watch it slither away into the distance wondering to what fascinating places it might be going, or else cling to it stubbornly in spite of its efforts to shake us off.

By the way, I was converted to the idea of space feudalism being plausible. Humanity expanded across the stars, but suffered some kind of social and cultural catastrophe as a result. Their machines advanced to the point of being dangerous, so they waged war on the machines in the Butlerian Jihad. Feudalism didn’t bring humanity to the stars; humanity, having reached the stars through some advanced social system, reverted to feudalism, a feudalism modified with the remnants of the technology built up in ancient times.

Foreshadowing

But I wouldn’t have read on for long enough to care about the Butlerian Jihad unless the foreshadowing was laid on thick. The switches between different characters and their points of view, the dense undergrowth of exposition – these are not fashionable in sci-fi/ fantasy writing today. But anyone who notices these unfashionable features and concludes that they are dealing with a clumsily-written book is mistaken.

When we ‘observe the plans within plans within plans’ we begin to wonder how these plans (within plans within plans) will work out. The story does not go from A to Z, from safety to danger. It goes from Y to Z, from less extreme danger to more extreme danger. We know the Harkonnens are going to attack. The Atreides know it. If they didn’t, the book and its sympathetic characters would be very irritating. We know Yueh is a traitor; if we didn’t, the revelation would be a pretty limp and predictable twist. We are not waiting to see if this Jenga tower will come down. We are waiting to see how.

While we are waiting for the Harkonnens to strike, we get sucked into the Duke’s administrative and political problems in a way that lulls and distracts us.

The writing and worldbuilding are open to criticism in places. I didn’t like how squeaky-clean and wholesome the Atreides were. ‘Good nobles’ vs ‘ bad nobles’ – come on. They’re an unelected ruling class who think they’re better than us. They’re all degrees of bad.

There’s a whole double-bluff intrigue where the Duke is pretending to be suspicious of Jessica. This is a tedious sub-plot, totally far-fetched. It’s just conflict for the sake of conflict. The book would be better without it. The mentat Thufeir Hawat is closely connected with this plot, but all in all I don’t see what he brings to the table. I think the book would pack a heavier punch if this sub-plot was gone and this character stripped back 90% or so.

Phallic sandworms

Paul is 15 but completely devoid of horniness or sexual neuroses; in the banquet scene, an attempt to seduce him falls flat. This is no doubt because of his Bene Gesserit training. But the repressed sexuality is central to the story. It’s more obvious to my grown-up mind that the sandworms are basically big dicks. And to paraphrase the book, who controls the big dicks controls the big dick energy. After Paul learns to harness and steer the big dicks, the climax of the story soon follows. Sorry for saying climax.

How does Frank Herbert get away with this insane sexual imagery? It’s even more obvious than King Solomon’s Mines. But it works because the sandworms work on their own terms. Arrakis without them wouldn’t be the same. Herbert doesn’t give a damn about space travel, but he cares about ecology. He reveals how this ecosystem works, and it is not a lecture we endure but a story mystery that is very satisfying to engage with and to solve.

Dune’s rich and strange hero

Speaking of Paul, even as a young reader I never quite liked him, and I never thought he was a good person. I rooted for him, and was invested in him. But I didn’t like him. He wrestles with his ‘terrible purpose’ and his visions of jihad for most of the story. As we read on, it becomes clear that is the story about the rise of a vast and terrible historical figure. It’s visible from the start, but the shock of the Harkonnen coup shakes something loose in him. As readers we come to respect the Fremen, but Paul is deceiving and manipulating them. Near the end (page 504) Gurney reproaches him when he reveals that he doesn’t really care about those killed in the final battle. He doesn’t care much about his murdered son either. And around the same time he finally embraces his ‘terrible purpose’ of galaxy-wide jihad; in his view there is no other way to cleanse the stagnant social order. The upheaval of the jihad will put a mixing spoon into the galactic gene pool and give it an almighty stir. This is the way he sees the world.

The unsettling presence of Paul’s little sister Alia is significant; he is only a little bit less weird than she is.

I haven’t read the sequels; I have been discouraged by some who have. What’s more, I consider the story complete and self-contained. It’s obvious to me that Paul is on track to become a genocidal god-emperor. There are no narrative questions left to answer.

The book suggests that Herbert does hold some beliefs that are repugnant to me: in the efficacy of eugenics, and in deep, inherent differences between men and women (‘takers’ and ‘givers’). He is cynical about humanity and believes that we will always be in thrall to religions and monarchs. But it seems clear enough that Frank Herbert doesn’t approve of Paul’s ‘terrible purpose’ or of the Bene Gesserit and their biological intrigues.

Atreides of Arabia

The ‘white saviour’ stuff is pretty blatant; Paul joins the Fremen and two years later has risen to be their messiah. This clearly takes inspiration from Lawrence of Arabia, and went on to inform Jon and the Wildlings, Dany and the Dothraki, etc.

With the Fremen, the Muslim coding is not just heavy but overwhelming. I didn’t see any problem with this when I was 15. But there was something more positive that I didn’t see either: that this is a text about the anti-colonial revolutions of the 1950s and 1960s. The Muslim stuff could be read as a tribute (perhaps a clumsy one) to the anti-colonial struggles of the Arabs, the Algerians, the Libyans. In fact the wikipedia page tells me it was also inspired by struggles of Caucasian Muslims against Tsarist Russia (hence, no doubt, the presence of a baddie named Baron Vladimir). The new film version appears to be leaning into this reading.

Conclusion

As an experiment, try to describe Dune in bald terms. It’s about a teenager who vanquishes his enemies and becomes emperor of the galaxy by convincing native people that he’s their god and by harnessing the power of huge phallic monsters.

When you put it like that, it actually sounds embarrassing.

What rescues Dune from being ‘That book that every guy loves for some reason?’ What raises Dune above the level of a basic power fantasy?

First, the world and the hero are so strange. Neither invites you in. You are forced to approach as a stranger. Paul is not the avatar for your fantasies; you end up walking many miles in his stillsuit, but you are never at all comfortable in it.

Second, it’s primarily a story about ecology and religion, not violence. It’s a story that forces us to pay attention to things we take for granted in life, such as water and faith. The indigenous people, taken for granted above all others, turn out to be the key not just to Arrakis but to the universe. It’s a book that humbles the reader, that confronts the reader with vast superhuman forces.

Last, it forces to reader to consider the cost of power. The more Paul masters these forces, the more alienated we are from him as a character. The Fremen are liberated, so it’s a satisfying ending. The ‘plans within plans within plans’ produce the most terrible blowback – for the Emperor, for the Harkonnens, for the Bene Gesserit. But Paul has reached a place where he is both all-powerful and inhuman. The worst blowback might be for the billions of innocents who will die in his jihad.

Everything feels earned. It feels earned because the desert exacts a terrible price for every blessing it gives, and there are no happy endings in this social order.

Appendix:

A note on Dune and videogames.

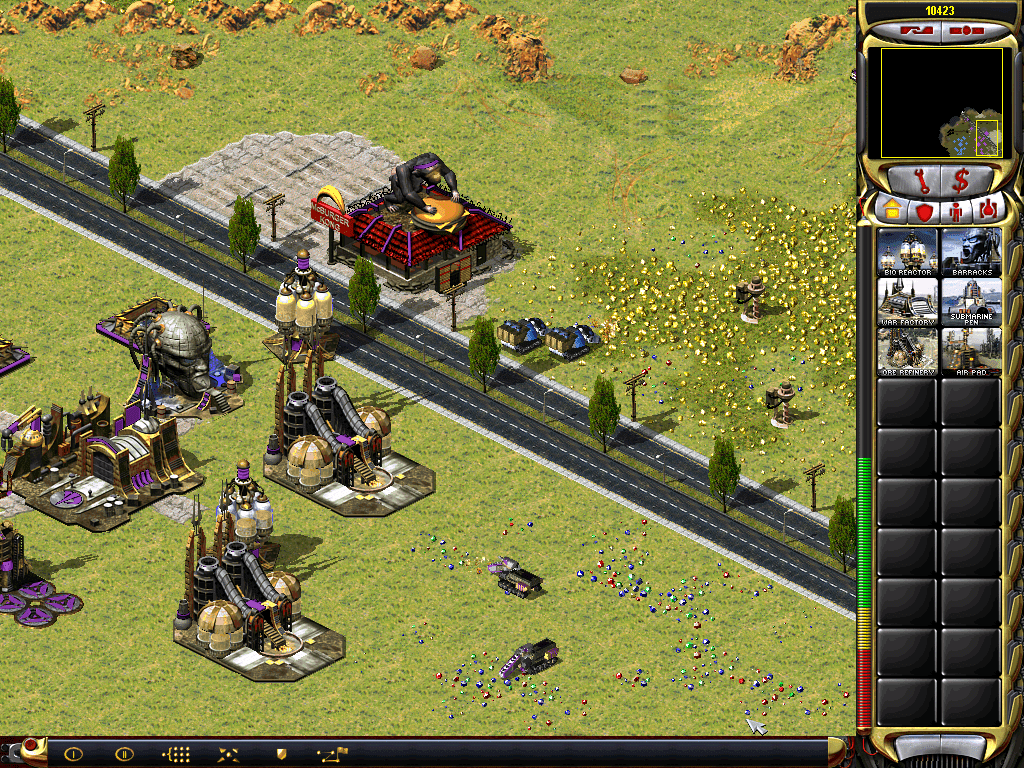

Dune 2 was the first strategy game, and it adapted straight from the novel a model of resource-collection that went on to exert a huge influence. There is a single resource, the spice, which lies on the surface of the ground. It is collected by huge harvesting vehicles. In Command and Conquer, the spice became tiberium, which has its own interesting back-story but is functionally identical, with the big harvesting vehicles and all. In the Red Alert spin-off, the spice appears in an alternate-history Cold War setting as Ore, a single one-stop-shop resource. Armies supply themselves by mining this resource on the battlefield. Helpfully, it is spread in pockets evenly across the surface of the earth from Manhattan to the Siberian taiga.

So when Frank Herbert wrote about spice-harvesting in the early 1960s, he was creating a model which videogame developers would still be using in the 21st century. It was such a useful model for gaming that the plausibility of the game world of Red Alert was stretched to the limit just to accommodate it.

3 thoughts on “How Dune gets away with it”