A British officer named Gough, before being sent out to the Baltic to join the ‘crusade’ against the Russian Revolution, spoke with Winston Churchill in London:

Pacing about his room and constantly referring to a map of Russia on the wall, Churchill optimistically explained to Gough how the various invasions then under way against the Bolsheviks – Kolchak from the east, Denikin from the south and the British from the north, together with the one proposed by General Iudenich from the Baltic – would encircle and crush the Reds. ‘He seemed to overlook the scale of the map,’ Gough noted, ‘and that these four movements, separated by immense distances, were handicapped by very inferior numbers and equipment […]’

Churchill dismissed these arguments: ‘Bolshevik morale was low and the resolute advance of even small armies would cause their organisation to disintegrate.’[i]

This is a short post in Revolution Under Siege, a series about the Russian Civil War. There are theatres of the war which I have neglected in the main narrative. I have never been quite so crazy as to think I can write this series as a comprehensive history of the war. In this short post we will deal with one of these neglected areas: the Baltic, specifically Estonia and Latvia.

Estonia and Latvia

Estonia and Latvia, proudly independent states today, were until 1917 mere provinces of the Russian Empire – though like Poland they were more industrially and commercially developed than Russia itself.

The main landowners were all to be found among the ‘Balts,’ a privileged German minority of 10% or so. These Baltic barons were more German than the Germans (like the Nazi Alfred Rosenberg) and more Russian than the Russians (Like Budberg and Ungern-Sternberg) but dismissive of the language and culture of the majority. Their wealth and titles rested on the labour of Estonian-speaking and Latvian-speaking farmers. In the cities lived the cultural melting pot that was the working class – Estonian, Latvian, Lithuanian, Polish, Jewish, Russian, German and Belorussian. Among the middle classes and professionals, here as in many European countries in the era, national pride was awakening.

In 1917, Estonia and Latvia were Bolshevik. This will not be a surprise to readers who recall the key role of the Latvian Rifles in 1918.

For reasons we have discussed before, the Constituent Assembly elections of December 1917 gave a massive and unfair advantage to the Right SRs. Even so, the Bolsheviks won 40% of the popular vote in Estonia – as against 32% for the Estonian Nationalists. In Latvia, the result was 72% for the Bolsheviks, 23% for the nationalists, the highest Bolshevik vote of any electoral district in the whole of the former Russian Empire.

Tallinn (Capital of Estonia, then called Reval) had its own October Revolution a day before the events in Petrograd, when Jan Aanvelt declared a Soviet Republic. In the first week of November, every major city in Estonia declared for the Soviet power.

‘The Doom of Soviet Latvia’

But already by mid-1917 the German military had conquered Riga (Capital of Latvia). In February 1918 the Germans renewed the offensive, conquering Estonia. Part of their casus belli was that they wanted to ‘protect’ the Baltic German barons from having their lands taken off them.

On February 22nd the Soviet government debated whether to accept the Brest-Litovsk Treaty, which would effectively hand over Latvia and Estonia to the German Empire.

Stupochenko, who took part in the debate, described its conclusion: ‘The fraction decided by a majority to sign the treaty, making voting compulsory for all Bolshevists [sic] except the Latvian comrades, who were permitted to leave the room before it took place, since they could not be expected to take responsibility for the doom of Soviet Latvia.’[ii]

The offensive and the treaty destroyed the revolution in the Baltic States. These were grim days for the working class. German occupiers put the Baltic German barons back in charge and destroyed the Soviets. My Anglophone sources are silent on how the occupiers treated the Bolsheviks and other socialist parties, but they tell me that the liberal nationalist politicians were scorned by the occupiers, now and then locked up; but that in general the period of German occupation was favourable to them.

Evan Mawdsley phrases this in a curious way. Nine months of ‘relative stability’ gave a chance for ‘national consolidation.’ I would word it differently: nine months of military occupation destroyed the workers’ revolution and gave the wealthier classes a breathing space to rebuild their hegemony. Under the protection of the Germans, Russian White Guards began building armies in Estonia and Latvia. The Baltic States began serving as ‘a kennel for the guard-dogs of the counter-revolution.’[iii]

Revolution

At the start of November 1918, with revolution and surrender in Germany, everything changed. In Estonia and Latvia a new, dynamic, complex situation emerged. New states, foreign intervention, revolutionaries and counter-revolutionaries were all in the mix.

British historians (see Kinvig and Mawdsley) tend to take the British ruling class at its word. It goes without saying, for them, that the Germans and the Soviets were up to no good but that the British armed forces intervened in the Baltic area to defend small nations and democracy.[iv] The Estonian and Latvian nationalists who eventually won are treated, in a teleological scheme, as the only legitimate local forces.

These parties and institutions are referred to by the name of their respective country – so it’s ‘Estonia’ against ‘the Bolsheviks,’ treating the former as the very embodiment of an entire nation and downgrading the latter to a wretched bunch of interlopers.[v] They will acknowledge that Estonia and Latvia had ‘significant groups of Bolshevik sympathisers among their population,’ but also say that they were ‘invaded by the Bolsheviks… under the guise of creating a federation.’ The British, meanwhile, wish to ‘come quickly to the aid of the new states.’ No ‘guises’ here.[vi]

I think we should start from a different perspective.

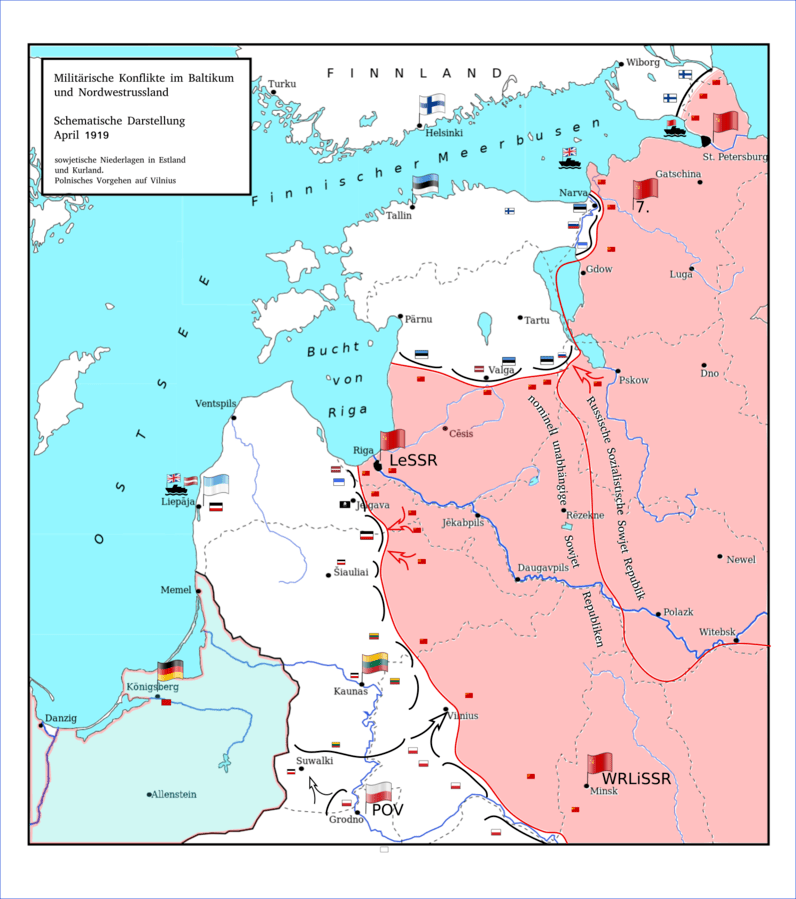

Civil War took place across the Baltic States, spilling over national boundaries. It was a class war with national cross-currents. As far as I can make out (reading between the lines of sources which are not interested in such questions), the main class forces were as follows:

- The old landowners (Baltic Germans), eager to restore their privileges – supported by the German military.

- Professionals and business owners, rallying a part of the workers and peasants under the banner of national freedom – supported by the British Empire.

- Workers (of a range of nationalities) seeking to combine national freedom with socialist revolution – supported by the Soviet Union.

- …and there were White Russians in the mix, allying variously with Germans, Allies and nationalists, but always against the Soviets.

Let’s flesh out this simple schema by introducing some of the concrete forces and events involved.

Germans, British and Whites

First, meet General Ruediger Von Der Goltz.[vii] Right when the Allies were cooking up the Versailles Treaty with the aim of trampling Germany into the ground, they were allowing thousands of German soldiers to represent German imperialism in Latvia. Against the Reds, any ally was a worthy ally.

By 1918 the German occupation force in the Baltic was ‘demoralised, mutinous and frankly Bolshevik’[viii] but help was on the way. Von Der Goltz arrived in February 1919 and took over an area around Libau, Latvia. He had a powerful base of support in the form of the wealthy Baltic Germans, plus German volunteers who had fought under him in the Finnish Civil War. Then came the ‘Freikorps,’ those military veterans turned paramilitaries who had crushed the Spartacus Uprising of January 1919.

Within days of the Estonian and Latvian nationalists declaring independence in November 1918, the British navy was knocking on their doors and dumping thousands of weapons on their doorsteps. A little way into 1919, the armies of the Latvian and Estonian nationalists were kitted out from head to toe in British uniforms. The British fleet dominated the Baltic Sea and soon the Gulf of Finland, too. They sank Soviet ships in brief and one-sided naval battles, laid siege to the island fortress of Kronstadt, made daring raids into its harbour, ran agents in and out of Petrograd by boat, and lobbed shells at any Red Army unit that strayed into range near the coast. When the Red troops at the coastal fort of Krasnaya Gorka rose in a mutiny against the Soviets, the British supported them with artillery fire.

They also operated a kind of taxi service across the Baltic, ferrying White Russians, nationalists and Germans around to engage in talks; the British sometimes lost their patience in their attempts to get these mutually hostile forces to work together. They were the fixers. Without them the component parts of this anti-Soviet alliance would have been at each other’s throats.

The counter-revolutionary Russians who gathered their forces in Estonia constituted perhaps the most openly reactionary of the White Guard armies. There was none of the ‘keeping up democratic appearances’ that we get with Kolchak and Denikin; their recruits took the oath of loyalty to the Tsar.

But Estonia was exactly where a little bit of moderation would have gone a long way; the Whites and the Estonian nationalists fought side-by-side against the Reds, but their refusal to even consider granting self-determination meant the Estonians were not exactly ready to follow them to the gates of hell (or even, as it happened, Petrograd).

Rise and Fall

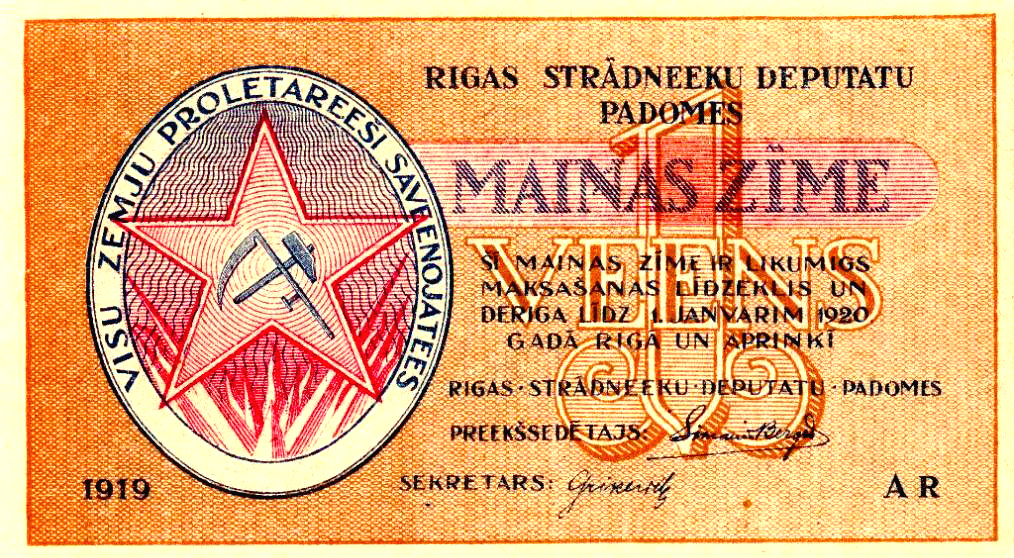

Early in 1919, the Latvian Soviet Republic made great gains, took Riga, and looked fairly secure. Meanwhile the Estonian Workers’ Commune established itself in the east of Estonia and took on the nationalists. The Workers’ Commune was supported by the Seventh Red Army, and soon it was 40 miles from Tallinn.

But by summer this had all melted into air. Finnish, White Russian and British aid for the Estonian nationalists secured a military victory. The Red Estonians (and there were many) were defeated and driven into Russia.

British naval guns were used to ‘help put down a mutiny among the Latvian [nationalist] troops’ and then to support the Germans in an assault on the Red-held town of Windau.

So far, so much foreign intervention. But there was a political side to these defeats. The Latvian Communists were ultra-left, like their Ukrainian comrades. They engaged in ambitious economic experiments and refused to give the nobles’ land to the peasants. This was in stark contrast to the Estonian nationalists, who carried out an ambitious land reform programme and gained popularity. This is barely remarked upon by my sources but it must have been of decisive importance.

Late in spring, things had turned so sour for the Soviets that the White Russians were able to make an attack from Estonia onto Russian soil. This attack was defeated, but it seems it was only a probing attack; the real onslaught came in October.

Iron Division

Meanwhile Von Der Goltz had risen up against the Latvian nationalists. In April forces semi-connected to him took Libau and arrested the Latvian government, denouncing them as Bolshevik sympathisers. A few weeks later, he invaded Estonia.

His ‘Iron Division’ took Riga in May and 3,000 people lost their lives during ‘a veritable reign of terror’ in the occupied city. His ambition appears to have been to carve out a Baltic German state.

In June the Latvian and Estonian armies ganged up and defeated Von Der Goltz and his army. The British, ever with their eyes on the prize (smashing communism), brokered a peace deal which involved clearing the Germans out of Latvia.

With the Germans defeated and the new independent republics consolidated, the situation by the end of the summer was not quite so complex: there were now two small anti-communist states consolidated just to the east of Petrograd, armed to the teeth with British rifles… And playing host to thousands of armed and trained White Russians who would rather see them dead than independent.

And the British had a task for these White Russians.

Towards Petrograd

In late summer, a celebrated Russian general named Iudenich arrived in Helsinki. He had made his name inflicting heavy defeats on the Turkish army during the World War, and now he had been appointed commander of the White Guards in Estonia by Admiral Kolchak. British supplies began flooding in: 40,000 uniforms in August and September 1919 alone.[ix] Iudenich set out to take Petrograd, and by early October he was in the suburbs of the city.

But that’s a story for another post; this short post can at most serve as a prologue to that drama.

Let’s finish with a strange image that Kinvig gives us.[x] After the defeat of Von Der Goltz, the Baltic German force known as the Landwehr were not disarmed. Instead Harold Alexander, a Lieutenant-Colonel of the Irish Guards who was somehow still in his 20s, took command of 2,000 of them and led them to the front against the Reds. He campaigned ‘dressed in his Irish Guards uniform, but wearing Russian highboots and a grey astrakhan Cossack-type hat.’ I think this image sums up the strange features of revolution and counter-revolution on the Baltic.

Note:

By way of an appendix, I am getting a lot out of Clifford Kinvig’s book Churchill’s Crusade. It is heavily critical of British intervention – of course it is, since it is based on the testimony of the British officers who saw the fiasco first-hand. It’s a great book.

But one tic of Kinvig’s really annoys me: he relentlessly refers to the Red Army as ‘the Bolsheviks.’ The party was renamed in March 1918 to ‘Communist Party’ – and anyway, we are talking about the army, not the party. There were SRs and non-party individuals in high positions in the Red Army throughout the Civil War period. It’s true that 5-10% of the army were party members by late 1919. But obviously 90%+ were not!

By using the term in the way that he does, Kinvig is telling us how he sees the revolution: as the accidental triumph of a bunch of cranks. I hope this series has demonstrated that nothing could be further from the truth.

The non-party Red Army soldier and Red commander had various and complicated motivations; national defence, a desire to beat the landlords, a genuine ‘non-political’ ethos of service, state compulsion, etc. They would not have been surprised to be sneered at as a ‘Bolshevik’ by their conservative uncle or their kulak neighbour, they might be surprised that a historian is still using the term decades later.

Go to Revolution Under Siege Archive

[i] Clifford Kinvig, Churchill’s Crusade, 142

[ii] Erich Wollenberg, The Red Army, chapter 1. https://www.marxists.org/history/ussr/government/red-army/1937/wollenberg-red-army/ch01.htm

[iii] LD Trotsky, How the Revolution Armed, Volume 2: ‘Petrograd, be on your guard!’ – December 22nd 1919

[iv] It is accepted, after all, by a majority of people the world over that one’s own nation (whichever nation that might happen to be) is the only benevolent force in a dangerous world.

[v] Exercising hindsight in this way is not necessarily outrageous. But the contrast between the treatment of Estonia [applause] and Soviet Russia [Boo! Hiss!] is striking. Even the most enthusiastic Irish Nationalist historians do not refer to the underground Dáil Éireann of 1919 as ‘Ireland.’

[vi] Kinvig, 135

[vii] ‘Ataman Goltsev’ to the People’s Commissar for Nicknames, Trotsky

[viii] Kinvig, 136

[ix] Khvostov and Karachtchouk, White Armies, 12

[x] Kinvig, 143

2 thoughts on “Short Post: Baltic Revolution”