In the cities of Central Russia, hope contends with hunger. On the Eastern Front, the Red Army faces Kolchak.

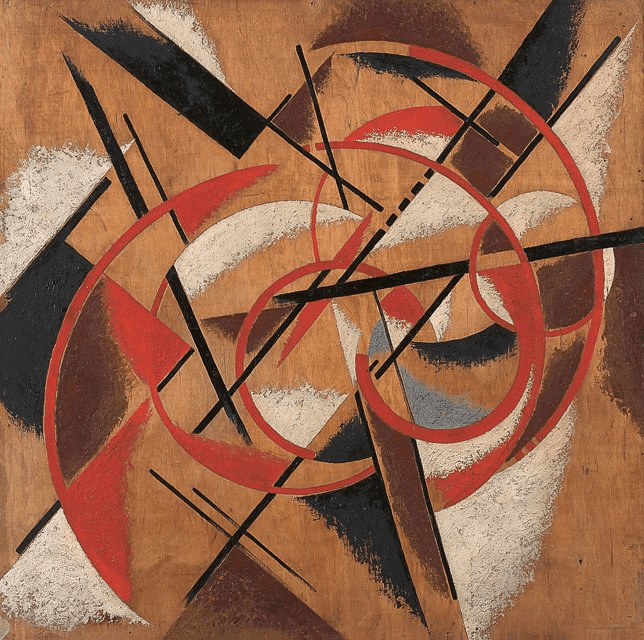

Red wedge and white circle are set on a canvas. The red wedge is slicing into the white circle. Around them smaller shapes are scattered, perhaps fragments shaken loose by violence, or forces of secondary importance in the conflict. It is an abstract image, but it is suffused with energy and struggle. The red object is not larger than the white, but it has shape, momentum, direction.

El Lissitzky painted Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge in 1919, the decisive year of the Russian Civil War. It is one product of the ‘tidal wave of artistic creativity’ which followed the Revolution. This was a golden period for the Constructivist and Suprematist schools, for Malevich, Tatlin, Popova, Rodchenko and many other artists.[i]

The Promise of Revolution

The innovation and excitement on the canvas (and of course in the work of poets and writers) was a reflection of the changes the Revolution promised. Serge remembers the officials of the new state apparatus hurrying through the streets: ‘men and women alike, young or ageless, carrying over-stuffed briefcases under their arms’ filled with dossiers, decrees, mandates – ‘the precious first drafts of the future, all this traced in little Remington or Underwood characters.’[ii]

The town houses of individual bourgeois families had been transformed into communal dwellings, housing multiple families. Better than the slums and barracks – or shelled ruins – they had come from. Palaces that had once housed princes and their mistresses now housed public institutions such as the Palace of Motherhood where modern maternity care was driving a wedge into an over-medicalised and patriarchal tradition. Public canteens served up nutritious meals for free. Families availed of public laundries and crèches.

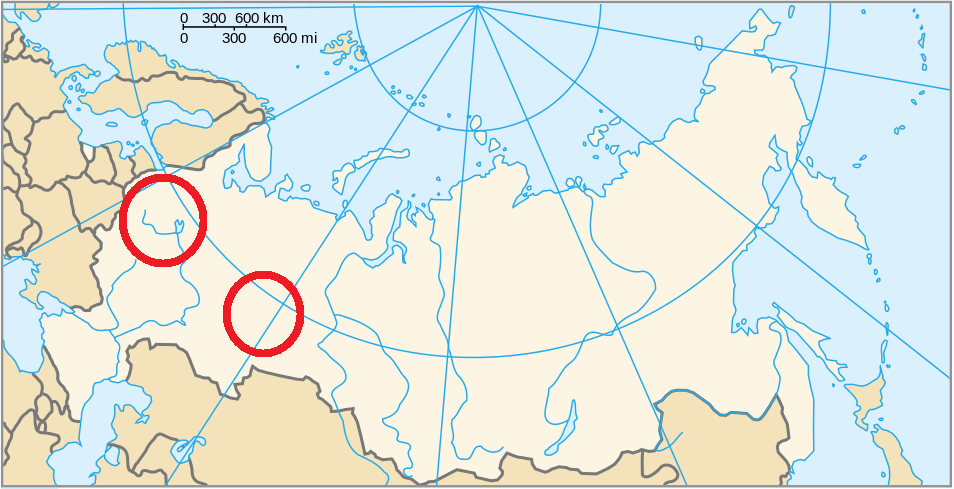

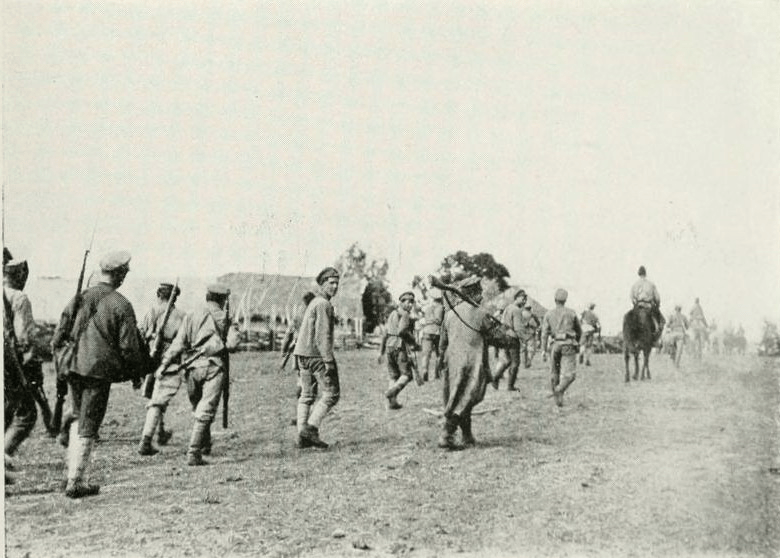

The promise of the revolution delivered on the frontlines too. In February, before the outbreak of Kolchak’s great offensive, the Whites faced a complication in the middle of their frontline when the Bashkirs switched sides to the Reds. The Bashkirs were traditionally a nomadic people. They were one of several ethnic groups like the Tatars and Chuvash who predominated in parts of the Ural and Volga regions (Lenin’s grandfather was a Chuvash tailor from the Volga). It was the Bashkirs who had named the Ural mountains, after their legendary hero who sacrificed himself to enrich the earth.

When the 6,000 Bashkir cavalry went over to the Reds, it was as I said a complication for Kolchak, not a devastating blow. But in hindsight it matters a great deal. The Bashkirs, who lived under a near-medieval social structure, were at first disoriented by a revolution they could not understand, and followed their chiefs and Islamic clerics into the White camp. But the Whites mistreated them and refused to give them autonomy. The Reds made a better offer. It was to be an early example of the decisive importance of the Soviets’ democratic policy on the national question.

Neil Faulkner writes of ‘the explosion of creative activity unleashed by the October Revolution,’ particularly in education. The country went from six universities to sixteen, in just over a year, and courses were open to all and free of charge. ‘The workmen crowd to these courses’, reported journalist Arthur Ransome. ‘One course, for example, is attended by a thousand men, in spite of the appalling cold of the lecture rooms.’ The number of libraries had doubled in Petrograd and tripled in Moscow. ‘In one country district, there were now 73 village libraries, 35 larger libraries, and 500 hut libraries or reading-rooms.’[iii]

A Hungry Winter

These are only a few examples of the sweeping social changes. But the winter of 1918-19 was bleak beyond description. A wreck of an empire emerging from the most terrible war in human history into the disruption attendant upon revolution – these would have been years of hardship even in the best possible scenario. Now, on top of that, civil war had thrown transport and supplies into complete chaos. The food supply system had been broken by the Great War. In 1918 the Soviets had taken grain by force from the villages to avert starvation. Many of the peasants hadn’t bothered planting.

There was no international famine relief effort to speak of. The American Red Cross made a difference – but their activities were confined to Siberia. The Fridtjof-Nansen scheme attempted to feed civilians in both zones. It showed what might have been possible if the rulers of the world had responded with humanity and compassion rather than with an all-out crusade against the revolution. But it was the exception rather than the rule.

The Soviets had nationalised industry and given land to the peasants; for this crime tens of millions of civilians would be collectively punished with the weapon of mass hunger, like the German civilians during World War One, or the Iraqi and North Korean civilians under sanctions in more recent years.

The city and town dwellers of Russia, their immune systems weakened by hunger, became easy prey for typhus and the so-called ‘Spanish Flu’ pandemic. Factories were short of supplies, understaffed by the hungry and the sick. Things were worst of all in Petrograd – a city with no farming hinterland from which to feed itself. Kollontai, the Bolshevik minister who was behind the Palace of Motherhood and other impressive projects, joked bitterly that ‘there is a great deal of moral satisfaction in deciding whether you want thick cabbage soup or thin cabbage soup.’[iv]

The industrial workforce fell from 2.5 million in 1918 to 1.5 million in 1920.[v] Where did all the workers go after the workers’ revolution? Hundreds of thousands into the Red Army; tens of thousands into the state apparatus; millions to the countryside, where food was more plentiful.

In the novel Conquered City, we see a crowd of exhausted and angry factory workers in Petrograd. Timofei sees the sad contrast between this crowd and the same crowd just a few months ago:

This crowd is spineless. The best among them have left. Some are dead. Eight hundred mobilised [for the Red Army] in six months […] they say [Leonti] died in the Urals. Klim is fighting on the Don. Kirk is head of something. Lukin, what happened to Lukin? Timofei could still visualise these veterans standing in this very shop, three or four ranks of men, successive generations who had come up and disappeared within a year. Gone. At the head of the army, at the head of the state, dead: heads riddles with holes, lowered into graves in the Field of Mars to the sound of funeral marches. The Revolution is devouring us. And those who remain are without a voice, for they are the least courageous, the most passive…[vi]

Peace Offensive

There was cause for hope that things would improve soon. Moscow had launched a ‘peace offensive’ in late 1918. They were offering to let the Whites and their Allied backers hold onto whatever territory they held in exchange for a peace treaty. It was the same basic equation as Brest-Litovsk the year before: space for time. The Soviets had the most to gain from time and the least to gain from war.

The call reached some receptive ears in the west. The Allied leaders were not all on the same page with regard to Russia. The Whites had basically failed in 1918, and many Allied leaders were growing tired of betting on losers. Some, such as Lloyd George in Britain, worried about what might happen even if these losers were to win. The Allies would be responsible for forcing a vicious reactionary regime onto Russia against the will of its people; Lloyd George saw that this would give labour and communist parties ammunition against the establishment.

So in January 1919 a radio broadcast went out from the summit of the Eiffel Tower inviting the Red and White leaders to a peace conference at the Isles of Prinkipo near Istanbul.[vii] In early March the US official William Bullitt was in Moscow offering generous terms for a peace treaty.

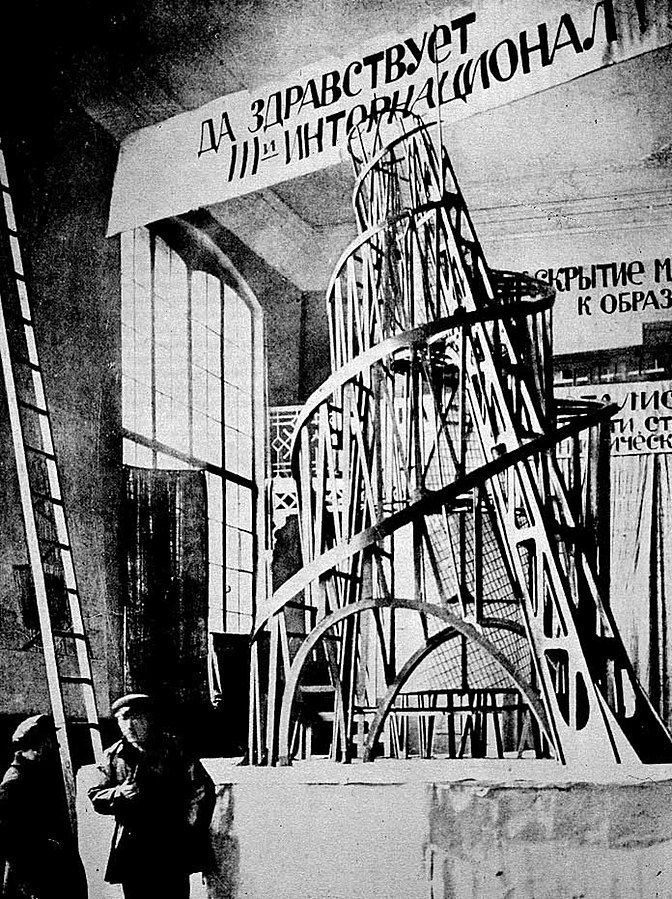

There were other promising developments. The partial bans on the Social-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks were lifted. Strict limits were placed on the power of the Cheka (a quick reminder, the Cheka was the police force which imposed harsh security measures). Central Europe was in the throes of revolution. Southern Europe appeared not to be far behind – see the factory occupations in Italy and the ‘Triennio Bolshevico’ in Spain. In March 1919 the first Comintern Congress met, founding a new communist workers’ international. The artist Tatlin designed an elaborate tower to serve as its headquarters.

But as we saw in Episode 11, in March Kolchak launched an offensive all along the Eastern Front. Kolchak had been enraged by the Eiffel Tower broadcast, and his offensive was in large part intended to cut off the possibility of a peace treaty. In this it was a complete, unqualified success. The advance through the Urals convinced the Allies that the Reds could be crushed, so they made another throw of the dice. The Istanbul conference never happened. Now the Allies were all in.

‘Everything for the Front’

For civilians in the Red zone, the advance of Kolchak meant new sacrifices – of food and raw materials, of men and women, of energy and time. War production – weapons, boots, uniforms – would remain the priority over civilian production. The slogan was ‘Everything for the Front.’

But hadn’t the people already given everything? Just a few months ago it had sent a levy of thousands of communists and trade unionists into the battle for Kazan. But somehow new reserves were found. A fresh levy of thousands of activists volunteered and went from civilian life into the Red Army. It is a measure of how genuinely popular the Revolution was. It is proof of the fact that great masses of self-sacrificing activists were its lifeblood.

This blood was plentiful but still finite. Sending the best administrators and the most politically active and talented workers into the Red Army meant further impoverishing civilian life. Producing more rifles and uniforms and boots meant not producing consumer goods. Not producing consumer goods meant it was impossible to trade with the countryside. No trade meant that the seizure of foodstuffs from the village had to continue. For every victory at the front, the people were forced to pay a heavy price. For every victory at the front, the Soviet Union was forced to pawn more and more of its assets – Soviet democracy, relations with the peasants, the support of the working class – with the knowledge that they could only be redeemed at great cost, and the fear that they might never be redeemed at all.

Limits on the Cheka and decrees on legality did little or nothing to curb the terror. Contrary to what certain scholars profess,[viii] the Red Terror was not a product of any lack of regard for human rights or the rule of law. It was rather (and the same goes for the White Terror) an expression of the extreme intensity and bitterness of the conflict. The war intensified in early 1919, grew more complex, more threatening. Accordingly, terror on all sides escalated.

Who was the new Soviet state official, carrying some first draft of the future in their briefcase? Perhaps their factory’s Soviet delegate, or that of their regiment or village, or some party activist going back years, recruited to some job in the administration of the new state. They would read appeals in the papers, hear them at meetings and rallies, urging them to go to the front. They would talk the matter over with comrades and loved ones. What entered into the decision? The fear of a bloody White victory. The prospects for revolution in Germany. Maybe lower motives, like a desire to escape the squalor of the city, or to make a name for oneself as a military hero.

They would decide to take up a rifle and go to the Urals. They might take a day or a week to settle their affairs, then they would go out on the railways across a countryside that was rife with discontent. Entering the Iaroslavl, Ural or Volga military districts, they would take their place in the rear. Here were 147,000 Red Army soldiers, only 18,000 armed – one in seven. The other six would be on transport, supplies, logistics, policing. This was an army without training centres or supply depots. New recruits were simply rushed to their units and there (usually) trained and (sometimes) equipped. This was anything but a streamlined red wedge.

In one of these rear military districts, the Middle Volga, there was a peasant guerrilla campaign against the Red Army. It fought under the confused slogan ‘Long live the Bolsheviks, Down with the Communists!’ How to explain this? The Bolsheviks had given the land to the peasants, and then under the new name of ‘Communist Party’ had come back a few months later to seize their grain. An Extraordinary Tax imposed in November 1918 had proved desperately unpopular, and the civilian Soviet administration was guilty of ‘manifest malpractises.’ Of course it was, if the best people had been poached by the Red Army.

Having passed through the rear areas, the volunteer would arrive at the eastern front.

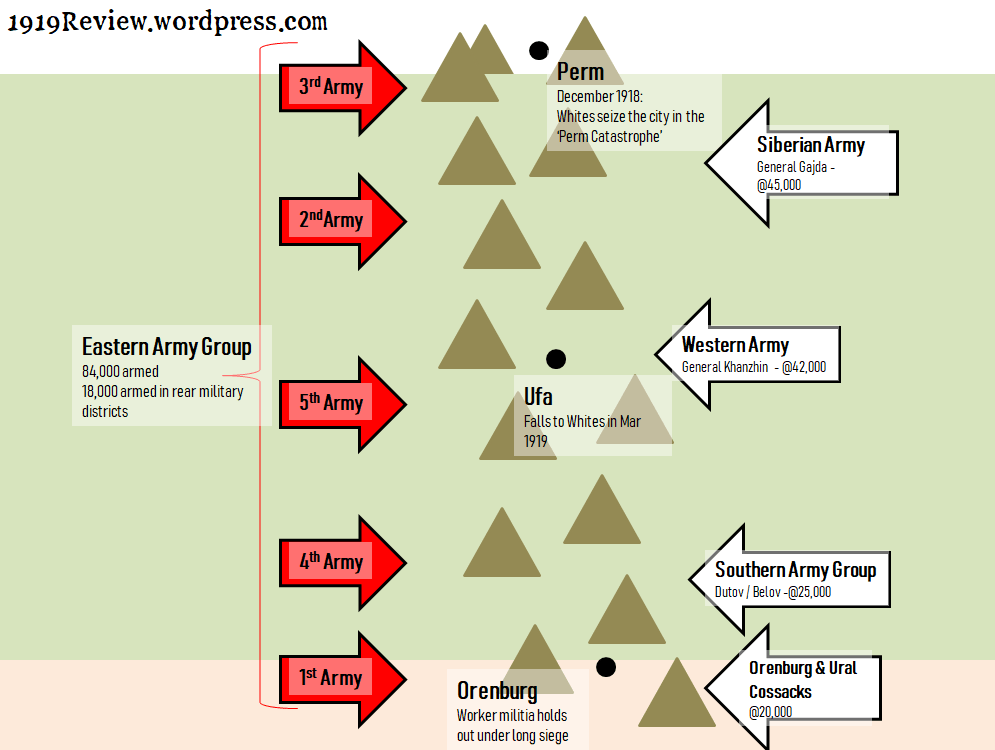

The front against Kolchak was huge and complex (though in scale it did not even approach the frontlines of the First World War). From Perm in the north to Ufa in the centre and on to Orenburg in the south is a distance of over 700 kilometres. While they stretch a long way north to south, from snow to sand, the Ural Mountains are nowhere near as tall as the Andes or the Himalayas. Nonetheless, they represent a barrier with dense forests and steep, rough ground.

Five Red Armies were distributed across this front, billeted in the villages or in the mining and factory towns. Each Red Army numbered between 10 and 30,000, to a total of 120,000. Here 84,000, two in three, were armed. It was not a case of ‘every second man gets a rifle’ or anything so absurd. The unarmed were driving wagons, carrying stretchers or cooking dinner.

Now let’s look at the other side of the frontline, once again surveying the situation from north to south. There was a White army of 45,000 around Perm and another, 48,000-strong, at Ufa in the middle. In the south were two loose armies of White Guards, Cossacks and others, one numbering 20,000 and another numbering 25,000, who had been fighting against Red Guard militias around Orenburg on-and-off for over a year.

I have remarked that Kolchak was a landlocked admiral, but the irony is spoiled by the fact that Russia is a land of massive waterways and on this eastern front there was a naval struggle between Red and White flotillas on the Volga and Kama rivers. Here the Reds had the advantage thanks to the sailors of the Baltic fleet. This advantage on the water meant they could outflank Gajda on the land. The Czech officer had covered himself with ostentatious honours after his victory at Perm, but now he was on the back foot.

Back on the Red lines, the newcomer would have found the Red Army in a state of internal struggle and rapid change. In early 1919 a new culture of discipline still contended with the Red Guard and guerrilla mentality. In March the 8th PartyCongress thrashed out the arguments even as Kolchak was advancing. In a political victory for Trotsky, the delegates came down on the side of the centralised, disciplined, professional army. A congress decision is instant, but the implementation of the decision in the real live Red Army would be a more difficult matter.

The Whites Falter

Having conquered an area the size of Britain, the Whites dug in from April into May as the spring floodsmade the roads impassable. But challenges emerged in the new territories. In Siberia, the land question was not the burning issue it was in Central Russia. So the regressive land policy of the Kolchak regime was not a huge liability. But the further west they advanced, the more of a liability it became.

In March the White vanguard had distributed leaflets proclaiming ‘Bread is coming!’ from Siberia. But, like all the contending forces in the Russian Civil War and in every war in Russian history to that point, the soldiers distributing these fliers were taking bread from the people.

In short, the people of the conquered territories had no reason to welcome the Whites.

Even at the high point of their advance, one anonymous White officer was pessimistic: ‘Don’t think that our successful advances are a result of military prowess. For it is much simpler than that – when they run away we advance; when we run away they will advance.’[ix] Here is a cynical but not entirely wrong view of the Civil War: retreat and attack as a function of inertia, not élan on the one hand or disintegration on the other.

In Mid-April Kolchak was at his height. But on the southern end of his front the worker militia at Orenburg still held out, a wedge sticking into his lines and forcing him to widen his front. A fresh attack by two divisions of his Fourth Corps ended in disaster on April 27th, when they were almost annihilated on a river bank near Orenburg.

Desertion was becoming a serious problem. An order to Red Army units from May 1st gives a vivid sense of what this meant:

Deserters from the enemy are to be received in a friendly way, as comrades who have freed themselves from under Kolchak’s lash, or as repentant adversaries. This applies not only to soldiers but also to officers. […] Enemies who have surrendered or who have been taken prisoner are in no case to be shot. Arbitrary shooting of men who come over from the enemy, as also of prisoners of war, will be punished ruthlessly in accordance with military law.[x]

This indicates that trigger-happy Red soldiers were still a problem. It also indicates that by May desertion from the ranks of Kolchak was occurring on a considerable scale. Finally this order shows us how, reinforced by the Congress decision of March, a new level of discipline was emerging in Eastern Army Group.

Red Advance

The Spring floods receded. In a few months, Eastern Army Group had tripled in numbers, from 120,000 to 361,000. The resistance at Orenburg made a concentration of forces possible, and on May 4th a mobile group went on the offensive. Soon the five Red Armies were on the move eastward again. The White Western Army, which had seized the town of Ufa in March, was driven back to the Belaia River. More Whites deserted. Red prisoners-of-war incorporated into the White ranks changed sides again at the first opportunity. The White force around Ufa had numbered 62,000. It soon withered to 15,000.

The fresh communist volunteer in the ranks of the Red Eastern Army Group would have encountered people like Vasily Chapaev, an NCO in the Tsarist army turned Red commander. In the 1934 war film Chapaev he is a truly magnetic character, played by Boris Babochkin. He is depicted as being in conflict with himself: he is very much the Red Guard leader, rakish and untidy, thundering around on a cart gesturing furiously. He only learned to read in 1917 and is not what a communist would call politically developed; he is not sure whether it’s the first, second or third international that he is supposed to support. But his bluster shows that these are deficiencies he is deeply ashamed of.

His commissar, a newcomer to the unit, has some of the men arrested for looting. Chapaev’s first instinct is to stick up for his men and to tell his commissar to go to hell, but once his initial rage has passed he submits in a dignified way to his commissar, and has the criminals punished. After this, he and the commissar work as a team; he dresses more sharply; he demands more of the soldiers.

For the purposes of the point I’m making, I don’t care whether these details are accurate in relation to Chapaev himself. Nor am I concerned with the realism of this or that battle scene. My point is that the key conflict in Chapaev captures in an authentic way the development within the Red Army at this moment. It was a decisive advance, not only geographically but in terms of organisation.

Meanwhile the real Chapaev was playing a key role in the advance of Eastern Army Group. On June 9th he led his 25th Division in a sudden strike across the Belaia River and seized Ufa. There they found huge reserves of food and grain.[xi]

Even the Third Red Army, much maligned after it was devastated in the ‘Perm Catastrophe’ of December 1918, recovered its fighting spirit and, on July 1st, recovered Perm itself.

On May 29th Lenin had said, ‘If before winter we do not take the Urals, I consider that the defeat of the revolution will be inevitable.’[xii] Perhaps he feared Kolchak consolidating his hold over the Urals, developing war industries there, with Allied aid pouring in all the while. He need not have worried. Never mind winter – by August, the White Guards had been cleared out of the Ural Mountains. The red wedge was cutting deep into the sphere of the Whites.

To finish where we began, the Bashkir cavalry had picked the winning side before it was clear who would win. But by late summer they would have been confident that their choice had been the right one, at least as far as the Eastern Front was concerned. They were the first of many minority peoples to come over to the Reds, really their first successful advance beyond ‘Great Russia’ since the outbreak of full-scale war in spring 1918.

The Revolution had won over the Bashkirs with the promise of autonomy and respect for their culture. Today the Autonomous Republic of Bashkortostan lives on as a direct descendant of the first Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. It has four million inhabitants, most of them Bashkirs and Tatars, and its capital is Ufa. This territory was wrested from the hands of ‘Great-Russian’ chauvinists by the advance of the Red Army in spring 1919.

Go to Revolution Under Siege Archive

[i] Conor Burke, ‘How revolution unleashed a tidal wave of creativity,’ Socialist Alternative journal, Winter 2017, pp 11-14

[ii] Serge, Victor, Conquered City, trans Richard Greeman, New York Review of Books, 1932 (2011), p 14

[iii] Neil Faulkner, A People’s History of the Russian Revolution, Chapter 9, World Revolution. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1k85dnw.16

[iv] Ibid

[v] Ibid

[vi] Serge, Conquered City, p 65

[vii] Smele, p 110. It was to Prinkipo that tens of thousands of Whites later fled. There, too, Trotsky was exiled from the Soviet Union years later.

[viii] Smith: ‘The Bolsheviks simply did not believe in abstract rights, and one consequence was that it left Soviet citizens bereft of a language in which they could seek redress against the arbitrary actions of the state.’ Russia in Revolution (p. 386). OUP Oxford. Kindle Edition. See also the essay ‘Red Tsaritsyn’ by Robert Argenbright

[ix] Smele, p 114

[x] Trotsky, How the Revolution Armed, Volume 2, Order 92, May 1st 1919

[xi] This episode is absent from the film. Beevor’s account (p 298) is a little unclear but he seems to suggest Chapaev was dead by February 1919 in which case his most significant military feat could not have happened. Either that or Beevor jumped forward a year, or it was a typo. As a brief update on my ongoing assessment of Beevor’s contribution, I am still getting good concrete details out of this book. He knows when to slow the narrative down to real-time and when to focus on an interesting character. His anti-communist bias is still obvious but generally not as intrusive as in the chapter I reviewed in detail. He hasn’t mentioned Lenin much in a while, so I haven’t been forced to visualise the veins standing out purple on his forehead. But there is something about his preoccupation with squalor and gore that nearly repels me. I think it’s a question of theme. What is he trying to say with this book? That Russia is a land of squalor and gore?

On the Chapaev film and on the commmoration of the Civil War more generally, this is fascinating: https://iro.uiowa.edu/esploro/outputs/doctoral/Children-of-Chapaev-the-Russian-Civil/9983777197702771

[xii] Mawdsley, p 203

4 thoughts on “14: First Drafts of the Future”