This builds on last week’s post about the Black Sea Mutiny. I finished by saying that the kind of class appeal we saw at Sevastopol – fraternisation and mutiny – was a general feature of the Civil War. As regards international class solidarity among the intervention forces, we have other examples to add to that of the Black Sea Mutiny.

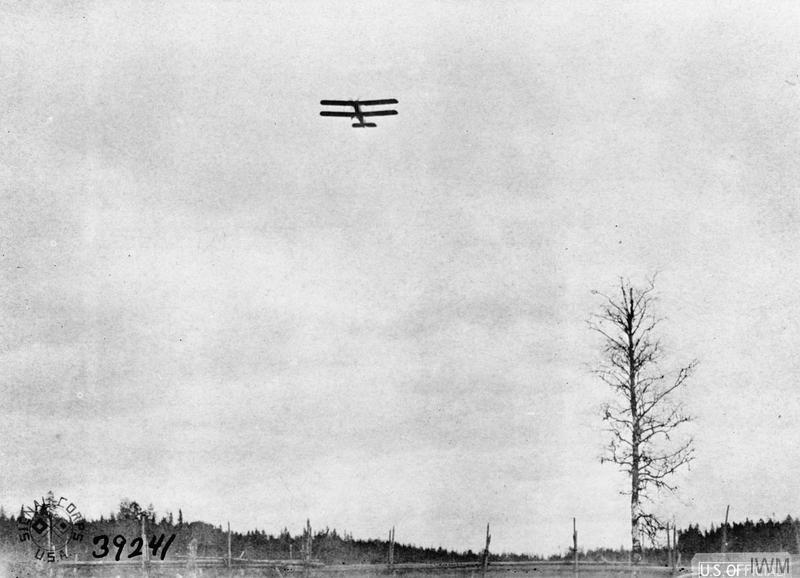

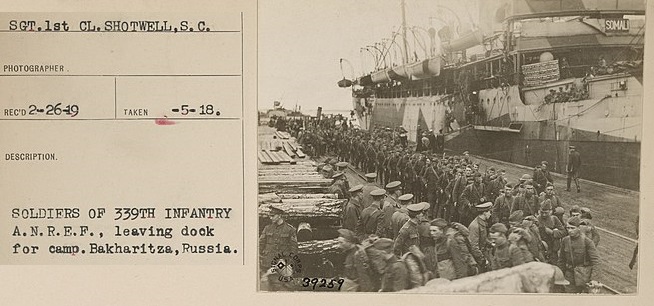

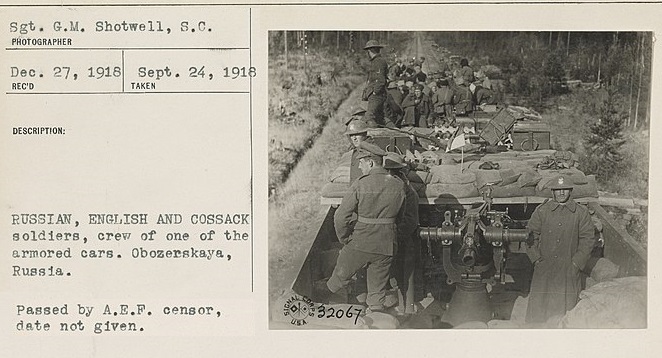

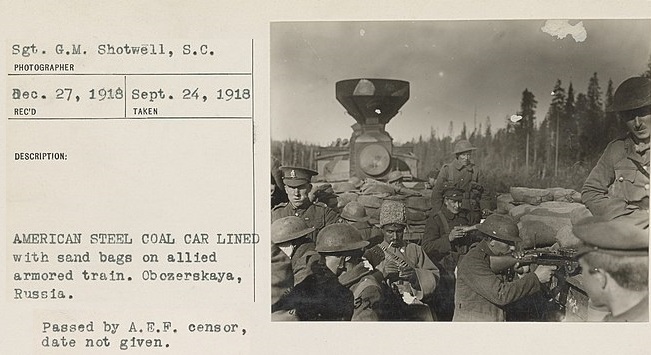

The main one I’m going to focus on is North Russia. The Northern Front represented a unique moment in history: the Russian Civil War was the only occasion on which the Red Army was directly in combat with British and US forces, and the Northern Front was where most of that happened. There were also soldiers from France, Italy, Serbia and a range of other countries. The small White Russian units could hold their own to an even smaller extent here than elsewhere.

The Youtube channel The Great War has a good video about the ‘Polar Bear Expedition,’ a 5,000-strong US force which fought in North Russia. There were mutinies, though nothing on the scale of Tiraspol, Odesa or Sevastopol. As the expedition dragged on morale declined. US troops wondered what the hell they were doing there. I was struck by this quote from a US soldier which is featured in the video:

The way these kids and women dress would make you laugh if you saw it on the stage. But to see it here only prompts sympathy (in the heart of a real man) and loathing for a clique of blood-sucking, power-loving, capitalistic, lying, thieving, murdering, tsarist army officials who keep their people in this ignorance and poverty. The majority of the people here are in sympathy with the Bolo [Bolsheviks] and I don’t blame them, in fact I am 9/10 Bolo myself.

Quoted in Damien Wright, Churchill’s Secret War with Lenin, p 128

Individuals with democratic values were not thrilled to have the White Guards as their allies. If pushed too far, many would have sympathised more with the other side. That was why their own governments did not dare to push them.

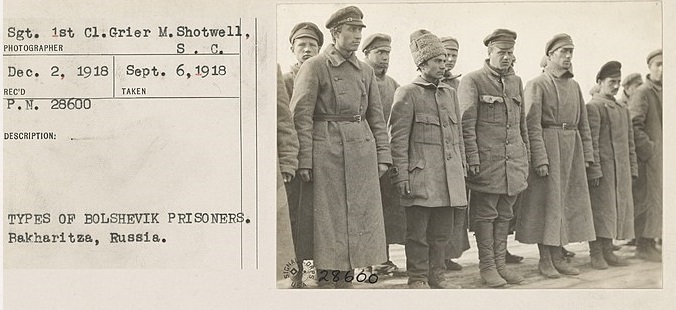

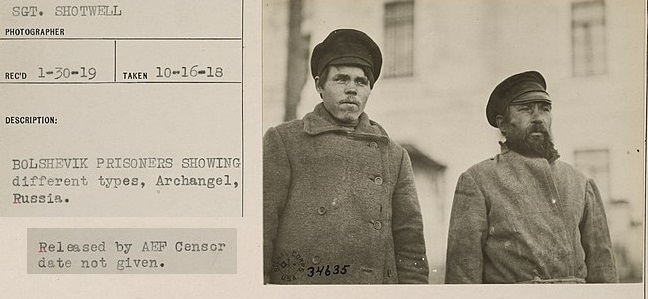

Meanwhile captured Allied and Central Powers soldiers were not mistreated but rather given teachers who spoke their own language and endeavoured to convert them to communism. In Beevor, naturally, such efforts (in relation to POWs from the Central Powers) are shown as Manchurian Candidate ‘brainwashing’.

I will give a brief description of one incident from the struggle on the Northern Front, during the Battle of Shenkursk in January 1919. Some thousands of Red Army soldiers advanced on a few hundred US troops, forcing them into a retreat. The retreating Americans were forced to wade through a valley filled waist-deep with snow, where dozens were shot down. Soon after, the important town of Shenkursk fell to the Reds. There ended the vague hopes of the Allies to link up with the northern end of Kolchak’s front. My impression is that there was no dazzling strategic or technological reason for this victory; the Red Army simply got a solid unit of a few thousand together, and got them to advance competently through difficult terrain. Their numbers and morale exceeded anything the other side had to hit back with.

Protests

Disease claimed many of the interventionists, and along with bloody defeats like the one at Shenkursk it’s no wonder the will to fight began to ebb. An anti-war movement developed in the US, and this movement was not one of Debs socialists and Wobblies as you might expect, but of the relatives of serving soldiers.

The ‘Hands off Russia’ movement in Britain developed later, in 1920, so I won’t mention it now. But its prelude was taking place: the growing clamour against intervention from the left and even some liberal MPs.

When Churchill wanted to send more troops to North Russia, he had two main stipulations: that they be volunteers, and that they not be told where they were going! Conscripts would mutiny, like the French; but there would be no volunteers at all if Churchill simply said, ‘Your mission is to freeze in the Arctic Circle just to help some Russian landlords.’

As we have seen, Allied troops did play an important role on the ground in Russia – British battalions garrisoned cities in Kolchak’s rear. Both Kolchak and Denikin were armed to the teeth by the Allies. But in early 1919 there was talk of whole British and French divisions being sent to help the Whites. On paper, this would have certainly defeated the Reds.

But there was a good reason why this didn’t happen. British, American or French troops would mutiny if there was a full-scale invasion. There would be anti-war movements at home. It might even prove to be the trigger for a British or French soviet revolution. Odesa, Sevastopol and Toulon served as a warning.

Japan

A side-note: the largest Allied intervention was that of Japan. 70,000 Japanese soldiers occupied eastern Siberia. Why didn’t they mutiny? I confess I know too little about Japanese history to answer, but I can venture a few guesses. Japan had won a war against Russia in 1904-5, meaning morale would be high for intervention in Siberia, which a patriotic Japanese person might see as Round Two. Nor had Japan suffered as badly in World War One; only 300 of its soldiers had lost their lives in that conflict – as against, for example 1.3 million French and colonial soldiers.

International Volunteers

A final note on international solidarity. The Red Army included thousands of German, Austrian and Hungarian ex-POWs, and Yugoslavs like Yosip Broz (AKA Tito); and it included thousands of Chinese labourers. International volunteers took part on the Red side in the Russian Civil War on the same scale as on the Republican side during the Spanish Civil War. They are less celebrated, probably for reasons that are unfair: because there were fewer English-speakers among them, and because there were fewer writers among them, and because their side won.

These international volunteers were, on the contrary, used in White and Allied propaganda; there was a myth that the Soviet regime was imposed on the Russians by Latvian and Chinese rifles. Why the Latvians and Chinese performed this service is not explained; and the same commentators treat the 50,000 Czechoslovak rifles as a sympathetic and benevolent presence on Russian soil. There is a related myth that the Red Army was officered by Germans, a continuation of the myth that the whole October Revolution had been a product not of Russia’s own social development but of ‘German gold.’

In reality the Red cause was an indigenous development. This can be demonstrated with reference to a series of revolts against the Soviet power which took place in the first three months after the October Revolution: the Polish Corps’ revolt in Belarus, the raids of the Orenburg and Transbaikal Cossacks, the uprisings in Irkutsk and Moscow, the battle outside Petrograd, the Kaledinschina. In each case a revolt by a well-armed minority was crushed by the mass mobilisation of local workers in their thousands or even their tens of thousands. It is true that the Latvians were among the very few cohesive military units the Soviet regime could call upon in the early months. But this only signifies that the elemental upsurge of local workers and poor peasants had not yet been channelled into a formal military organisation.

Go to Revolution Under Siege Archive