On the Eastern Front in July 1919, the White regime of Admiral Kolchak was reeling after its armies were driven out of the Ural Mountains. But the Siberian Whites made an audacious throw of the dice, triggering one of the largest battles of the Civil War.

To set the scene for us, here is the diary of General Alexei Pavlovich Budberg, a minister in Kolchak’s government. He recorded his horror and frustration as things fell apart:

July 19th 1919:

Head is spinning from work […] To our disadvantage, the Red Army soldiers at the front were given the strictest order not to touch the population and to pay for everything taken […] The admiral gave the same orders […] but with us all this remains a written paper, and with the Reds it is reinforced by the immediate execution of the guilty.

July 20th 1919:

[…] self-seekers and speculators are white with fear and flee to the east; tickets for express trains are sold with a premium of 15-18 thousand rubles per ticket.

July 22nd 1919:

The Ministry of Railways receives from the front very sad information about the outrages and arbitrariness committed during the evacuation by various commanding atamans and privileged rear units and organizations; all this greatly complicates the hard work of evacuation […]

Hints of a planned White counter-attack do not give Budberg any relief. On the contrary, he was filled with foreboding:

July 23rd 1919:

Something mysterious is happening at headquarters: operational reports have been temporarily suspended…

In the rear, uprisings are growing; since their areas are marked on a 40-verst map with red dots, their gradual spread begins to look like a rapidly progressing rash.

July 24th 1919:

The mystery […] has been aggravated: to all my questions I receive a mysterious answer that soon everything will be resolved and that very big events will take place that will drastically change the whole situation.

July 25th 1919:

Only today did I learn at headquarters that [General] Lebedev, with the cooperation of [General] Sakharov, wrested from the admiral consent to some complex offensive operation in the Chelyabinsk region, promising to completely eliminate the Reds […]

Undoubtedly, this is Lebedev’s crazy bet to save his faltering career and to prove his military genius; it is obvious that everything is thought out and arranged together with another strategic baby Sakharov, who also yearns for the glory of the great commander.

Both ambitious people obviously do not understand what they are doing; after all, the whole fate of the Siberian white movement is put on their crazy card, because if we fail, there is no longer salvation for us and we will hardly be able to restore our military strength…

Chelyabinsk

The city of Chelyabinsk lies amid a cluster of lakes, a few hours by rail east of where the Ural Mountains fall away to the plains. It can be regarded as ground zero of the Russian Civil War: it was there that a brawl between Czechs and Hungarians led to the revolt of the Czechoslovak Legion.

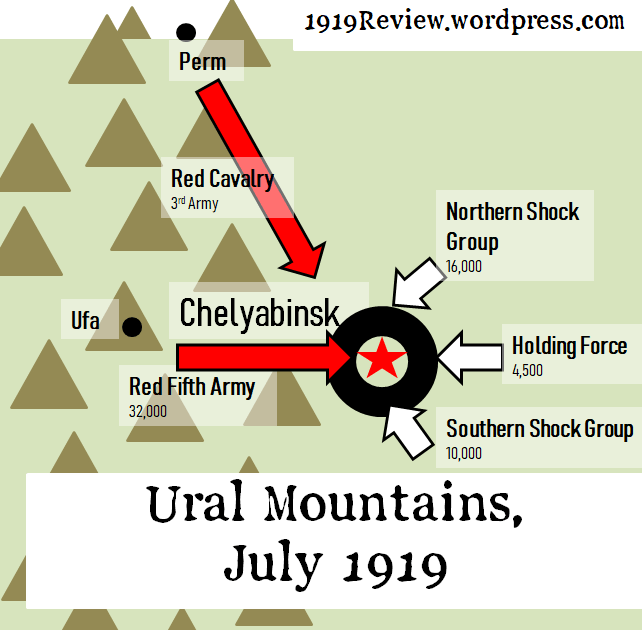

At the end of July the Red Fifth Army came down from the Mountains into the lake country. This was the same Fifth Army that had held the line at Sviyazhsk and then crossed the Volga to seize Kazan. Trotsky and Vacietis counselled caution and rest for Eastern Army Group after it drove back the White Spring Offensive. But the new commander-in-chief, the military specialist Kamenev, argued for a hot pursuit of the Whites right into the heart of Siberia. So far Kamenev had been vindicated. The same Chinese Reds, led by Fu I-Cheng, who had lost Perm the year before had recaptured it. The Red commander Frunze had taken Ufa after a terrible and bloody fight with Kappel.[i]

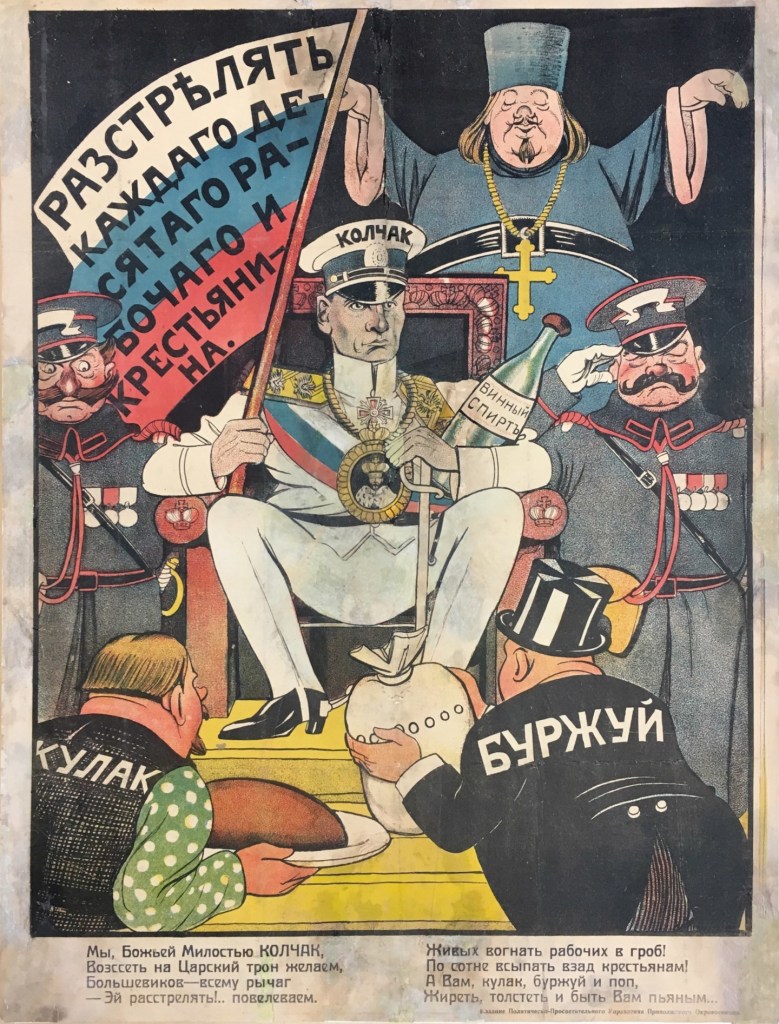

Now the Fifth Army was advancing on Chelyabinsk. But Kolchak, on the advice of his young generals Lebedev and Sakharov, had decided to turn the city into an elaborate trap. The Reds would be allowed to seize the city – then encircled in it, and destroyed.

On July 24th a workers’ uprising began in the city. It was led by an underground Bolshevik organisation that had suffered under the counterintelligence operations of the ‘very cruel’ Colonel Sorochinsky. The Red Fifth Army hurried to the aid of the rebels, and linked up with them. Railway employees sabotaged the White defence: they derailed one armoured train and diverted another into a dead end. The city fell, and the Reds captured many rifles and machine-guns. Morale was good, energy high: Red detachments at once began scouting and advancing out from the city through the suburbs and villages.

But to the north, south and east, White shock groups and formations were closing in on the city to encircle and destroy the Fifth Army.

Let’s pause and get a proper sense of scale. The last time this series zoomed in on a particular battle, that of Kazan, it was easy enough to visualise. In an arena measuring forty kilometres by twenty, there were between ten and twenty thousand soldiers per side.

The Battle of Chelyabinsk compels us to think bigger, on a scale of at least 80 square kilometres.

There were 32,000 rifles and swords in the Red Fifth Army. On the side of the Whites, there were around 30,000 as well: the Northern shock group numbered 16,000, the southern shock group 10,000, and there were 4,500 to the east holding the line between the two.

The Trap

Let’s zoom in on one of those fighters, a White cavalry officer named Egorov.

At four in the morning of June 25th Egorov was waiting with his regiment at a crossroads near one of the several lakes north of Chelyabinsk. Egorov’s Mikhailovsky Regiment consisted of 150 mounted soldiers – ‘rather motley,’ by his own admission, old and young, mostly infantrymen mounted rather than ‘real’ cavalry – along with soldiers on foot.

They were ordered to gather here before seizing the village of Dolgoderevenskaya, north of Chelyabinsk.

Egorov and his men were still stinging from the postscript added to their orders: ‘I advise the regiment commander, Colonel Egorov, to abandon this time the usual delay…’

Adding insult to injury, the Mikhailov Regiment was on time. They were waiting in the early hours of the morning for the Kama Division to show up.

‘To the right and left I hear voices: “Why wait for the Kamtsy?.. Move!.. Enough of the Reds!”’

Egorov decided it was time. The regiment sneaked up close to the village. A local Cossack boy told them there were many Reds in the village, but a lot of them were asleep.

The attack began. White cavalry broke through the outskirts of the village without a shot being fired, and before most of the Reds were awake the White cavalry had dispersed all over the streets while infantry attacked from the west.

‘And only after that,’ writes Egorov, ‘the first rifle shots were heard.’

He was watching from a nearby hillside. The rifle fire intensified, and the sound of the Russian war-cry, ‘Urrah!’ came to him. After an hour of fighting, the Reds fled to the next village.

As Egorov entered the village he heard someone shout: ‘Mister Colonel! Trophies!’

His men were looting what the enemy had left behind: gramophones and field-kitchens. Egorov reckoned the Reds had, in their turn, taken the gramophones from the houses of priests and merchants.

But the Whites got carried away in the celebrations. The Reds counter-attacked and caught them unawares. Fortunately for Egorov, the Kamtsy arrived – the stragglers Egorov had not bothered to wait for – and they had artillery. By three in the afternoon the Reds had been driven back again. Egorov and his cavalry mounted up, and this time pursued them, and drove them out of the next village as well. The Reds began to retreat all along the front.

Egorov’s assistant, a Tatar, had taken a bullet in the arm during the day’s fighting. He was unperturbed. That night at dinner he drank heartily. Then he excused himself, went out into the hall, and removed the bullet with a penknife.

These battles were part of the advance of the northern shock group. It was very successful; it reached the Yekaterinburg-Chelyabinsk railway line, cutting off the Fifth Army and threatening it from the rear.

On 27 July the southern shock group advanced. Its purpose was to link up with the northern group, completing the encirclement. The southern group was commanded by Colonel Kappel, who had led the Whites at Kazan. Kappel was a relic of the late Komuch government and its ‘People’s Army,’ now serving Kolchak and the Whites. There were others present at Chelyabinsk for whom Komuch had served as a Red-to-White pipeline or gateway drug. The workers’ militia of Izhevsk were there, going into battle to the sound of accordions.

Meanwhile the 4,500 White Guards in the middle advanced west into the outskirts of Chelyabinsk.

Another White veteran recalled: ‘On one of the days, apparently on the 27th or 28th […] we found ourselves 3-4 versts from Chelyabinsk and were about to have dinner there.’

He and Egorov and Kappel had good reasons to feel confident. Many would have believed that just as Denikin was advancing in South Russia, they were about to turn the tide in the east.

Resistance

According to the plan, the Reds should have been panicking and falling to pieces by now. Generals Sakharov and Lebedev were young officers who had learned most of what they knew during the period of the Czechoslovak Revolt of 1918. They had led irregular detachments against untrained Red Guards.

But these Reds in Chelyabinsk were made of something else. They held firm. Kappel engaged in heavy battles to the south of the city, but his forces could not break through.

The Chelyabinsk revolutionary committee put out a call, and 8,000 miners and other workers joined the defence, arms in hand. 4,500 others joined work detachments, building defences and supporting the troops. The centre group of Whites could not advance further, and got bogged down in the outskirts.

Why couldn’t the Whites make any headway? We noted in a previous episode that they had raised two divisions of young conscripts. These forces had not even been trained when they were flung into the battle at Chelyabinsk. To encircle an enemy army would have been a challenge at the best of times. The White officers were ordered to spring the trap with personnel who did not know what they were doing.

In Russia, soldiers with rifles are called streltsi, literally ‘shooters.’ One veteran wrote to the Chelyabinsk local newspaper in the 1970s, recalling his days as an officer leading White streltsi:

I was a participant in the battles near Chelyabinsk on July 25-31, 1919, not in the Red Army, but in the White Army, in […] the 22nd Zlatoust regiment of Ural mountain shooters, which they practically were not [sic], since […] they were not even trained at all how to shoot.

During the battle, up to 80% of the 13th Siberian rifle division went over to the Reds. They surrendered in their thousands, bearing US Remington rifles and wearing British uniforms.

It wasn’t just the new conscripts. In the headlong retreat since May, divisions had winnowed to regiments, regiments to, in one case, a ragged group numbering only seventy. Typhus had raged through the White units. Many of the replacements were young Tatars, like Egorov’s friend. Many of these couldn’t speak Russian.

Kappel’s Volga Corps had taken a battering in recent months. Instead of getting time to recover, they, like the new recruits, were thrown into battle.

On the other side, the Red Fifth Army was experienced and energetic. And they had a political backbone: in the 27th Division alone there were 600 Communist Party members.

But the fighting was fierce. According to one source there were 15,000 Red and 5,000 White casualties.[iii] According to other sources, the Whites lost 4,500 killed and wounded, while 8,000 or even 15,000 were captured, and the Red casualties numbered 2,900.

The Reds held on in the centre and south, then reinforced the vulnerable north. They built up a shock group of their own and between July 29th and August 1st defeated five enemy regiments north of the city. I assume this involved sweeping through the villages Egorov and co had taken nearly a week earlier. Perhaps the gramophones changed hands again.

Cavalry units from the Third Red Army at Perm were hurrying to the aid of Chelyabinsk and threatened the Whites’ northern shock group. The Izhevsk militia was sent to meet them, but the Izhevtsi suffered heavy losses at the village of Muslyumovo. The northern shock group had itself suffered a series of shocks. Its position was untenable.

Back in Omsk, General Budberg was asked by Kolchak what he thought of the Chelyabinsk Operation.

July 31st

I reported to him that I think that now it is necessary to immediately stop it and order to do everything possible to withdraw the troops involved in it with the least damage to them.

The admiral was silent, but asked to speed up the dinner, then went into the office to Zhanen, where he signed a telegram to Lebedev about the retreat; he is very gloomy and anxious.

August 1st

Everything connected with the Chelyabinsk adventure, and most importantly, my powerlessness to stop it and prevent all its consequences, led me to the decision to ask the admiral to dismiss me from my post, and if it is impossible to give [me] a place to the front, then to [accept my resignation].

Budberg’s request was refused, and so he was forced to around Omsk as an agonised and impotent witness to further disaster.

Red advance

From August 1st the Reds were on the offensive. The White retreat eastward grew more chaotic.

Many in the White camp had warned against the Chelyabinsk operation. They favoured instead a defensive strategy: digging in behind the Ishim and Tobol rivers and buying time to train up the new units. After ‘the trap failed to close’[iv] at Chelyabinsk, the White armies were demoralised and sorely depleted. Digging in was less feasible than before, but even more urgent.

The Siberian Whites were not finished all at once. In late July the Siberian Cossack host joined Kolchak’s cause – too late to help at Chelyabinsk, but just in time to give Kolchak and others a false hope in a renewed offensive strategy. Nonetheless the Red advance across Siberia was indeed delayed by serious battles with the Cossacks and on the defence lines of the rivers.

Crisis in White Siberia

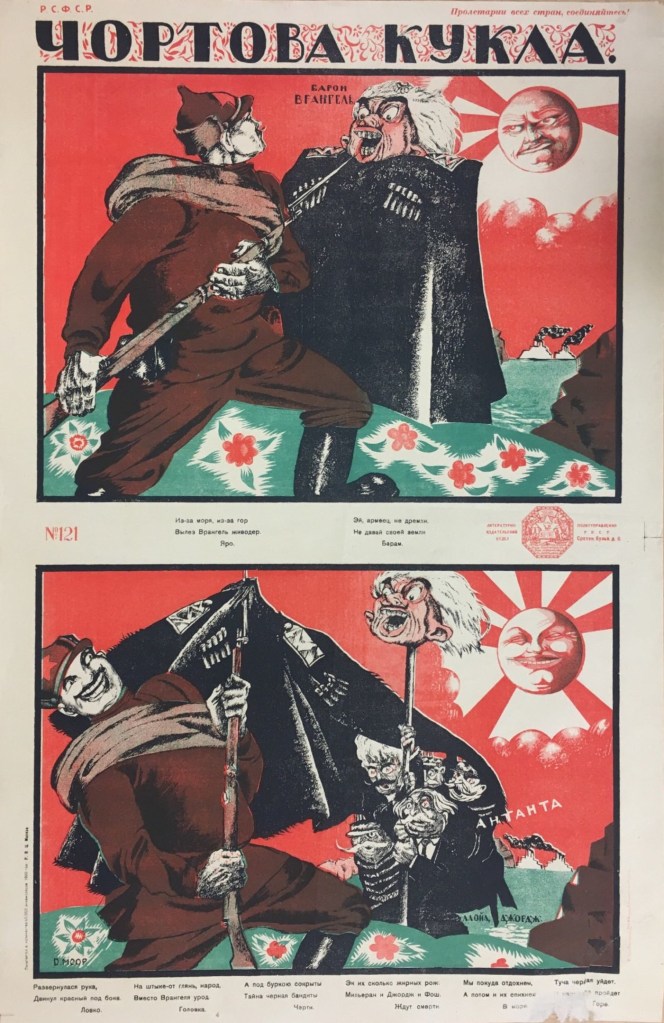

But the Battle of Chelyabinsk is not so much a story of Red victory as one of White defeat. That defeat is interesting because in every way it was symptomatic of the crisis that was developing in Kolchak’s Siberia.

Behind White lines there reigned a regime of corruption and terror that exceeds the most lurid caricatures of the Red side. Untrained and demoralised men sent to fight the partisans would torment the farmers, burn villages, loot, torture and kill. Bodies hung from the telegraph-poles along the Trans-Siberian railway.[v] Further east under Semyonov and Ungern, as we have seen, things were even worse.

Budberg lamented how among the middle and wealthy classes of the towns everyone felt free to criticise, but never lifted a finger to help in any practical way. It seemed everyone was out for themselves, embezzling without the slightest shame. In the White capital city, Omsk, many wealthy and well-educated people were concentrated. But the poor could not afford to eat and attempts by the state to provide the most basic relief or public services always somehow ended in a dead-end of bungling and embezzling.

The Czechs, whose revolt had given birth to the Eastern Front at Chelyabinsk the year before, were growing disgusted with the White cause, and becoming almost as much of a pain to the Whites in 1919 as they had been to the Reds in 1918. The first stirrings of mutiny were already evident. And in the woods the partisan forces were growing and developing. Meanwhile the Socialist Revolutionary Party were raising their heads again, active both among the partisans and the Czechs. They were the ghost at Kolchak’s feast: he had jailed them after his coup in November 1918, and shot many after the Omsk revolt of December.

Kolchak’s army had come to resemble, in miniature, the Tsarist army of 1917 – in June there had been cases of the men shooting their officers and changing sides. No wonder – the officers had brought back Tsarist practises such as flogging men and striking them in the face. In October, a mass of newly-raised conscripts was sent to the front, and melted away without a trace. Of 800,000 ‘eaters’, only one in ten were fighters; many soldiers travelled with their families in tow. They looted the locals to feed themselves. Some of their supply trains stretched out to 1,000 carts.

‘These were not military units,’ said one disgusted officer, ‘but some kind of Tatar horde.’[vi] Many of those fighting and dying were actually Tatars, so this is a fine example of all the cultural sensitivity we would expect from a White officer.

The battle at Chelyabinsk showed that a spectacular role reversal had taken place. In 1918, the Whites were the professionals, the elite soldiers, and the Reds were the undisciplined rabble. But the rabble had developed into an army. And on the other hand, when the Whites tried to move from elite detachments and all-officer companies to a mass army, they degenerated into a rabble. Their best units were better than the Reds, but their worst units were far worse. The Whites of 1919 were incomparably stronger on paper. But – and this was especially true in Siberia – they had the worst of both worlds. Compared to the early Red Guard formations, they had all the raggedness and all the indiscipline, but none of the political motivation.

Many on the White side noticed the change in the aspect of the Reds. ‘A White leader who visited Tobolsk after it was briefly recaptured was impressed at reports of how well the Reds had behaved.’ And General Budberg wrote that ‘we are not up against the sovdepy and Red Guard rabble of last year but a regular Red Army.’[vii] ‘Sovdep’ was a White nickname for the Reds, based on the words ‘Soviet’ and ‘Deputy.’ Budberg considered the Reds’ battle plans to be plodding and basic. But even basic plans were, in his view, better than none, or than the ‘too clever by half’ manoeuvres of Lebedev and Sakharov.

The Chelyabinsk battle also revealed another key weakness of the White Guards. On November 4th Kolchak complained that his army recruited from among ‘Bolshevik-minded elements’ who at the first opportunity ‘crossed over to the Red side.’ As a result, officers ‘refused to dilute their units’ with new recruits! ‘We had to recruit with great selectiveness, while the enemy freely used local manpower which was favourable to him.’[viii] In other words, the Whites were hindered by the small fact that most people didn’t want to fight for them, and favoured the Reds (even in relatively conservative Siberia).

It is true, as Beevor says (p 344), that ‘A civil war was not an election […] because the vast majority of people wanted to stay out of trouble.’ It is not possible to ascertain the will of the people by ballot in the middle of a civil war. We have to go with cruder measures, such as asking which side could reliably recruit thousands and which side could reliably recruit millions. Judging by this crude but immensely significant measure, the people preferred the Reds to the Whites.

Often the story of the Civil War is one of cruelty and dashed hopes. But the victory at Chelyabinsk was one worthy of a popular revolution. The workers’ rebellion at Chelyabinsk and the participation of thousands of volunteers in the battle underlines this democratic aspect.

The Battle of Chelyabinsk showed how Fifth Army had developed from the semi-irregular force that fought at Kazan into a professional army. But most of Siberia still lay before it, and far behind to the west, Tsaritsyn and Kharkiv had already fallen. Denikin’s advance on Moscow was already well under way.

Go to Revolution Under Siege Archive

[i] Beevor, 323

[ii] Smele, 113

[iii] Mawdsley, 210

[iv] Mawdsley, 210

[v] Beevor, 238

[vi] Mawdsley, p 211

[vii] Mawdsley, 208

[viii] Mawdsley, 214

The diaries of General Budberg came from militera.lib.ru_

In addition, this episode could not have been written without a collection of sources compiled by an internet user named igor_verh on https://forum.axishistory.com/viewtopic.php?t=192991. (The name at first raised alarm bells for me but the site’s description says it is apolitical. Its focus seems to be wargaming).

The sources are as follows, copied and pasted from the post:

http://war1960.narod.ru/civilwar/chelybinsk1919-1.html

http://www.book-chel.ru/ind.php?what=card&id=4415

http://www.hrono.ru/sobyt/1900sob/1919chelyab.php

http://kadry.viperson.ru/data/pressa/3/ … 983007.txt

http://chelyabinsk.rfn.ru/rnews.html?id=97133

http://city.is74.ru/forum/showthread.php?t=43062&page=2

Memories of M.V. Belyushin – the former ensign of 22th Zlatoust mountain riflemen regiment about battle near Chelyabinsk in the summer of 1919:

http://east-front.narod.ru/memo/belyushin.htm

The downfall of the 13th Siberian Rifle Division in the battles near Chelyabinsk in 1919:

http://east-front.narod.ru/memo/meybom1.htm

Sanchuk P. “Chelyabinsk operation in summer 1919”, publication in magazine “War and Revolution”, № 11, 1930:

http://elan-kazak.ru/sites/default/file … chuk/1.pdf

One thought on “18: The Chelyabinsk Trap”