At the climax of the Civil War, a White Army made a bold attack on Petrograd, the city whose working population and garrison had made the October Revolution almost exactly two years earlier.

The city was no longer called Saint Petersburg, and not yet Leningrad – as if to remind us that the Civil War-era Bolshevik regime was something separate not only from Tsarism but from Stalinism. But even within that era, Petrograd in 1917 and in 1919 were two different cities. Petrograd in 1917 was inhabited by over two million people; the city of 1919 had a population of 600-700,000. One was an industrial giant, the other had a skyline of idle chimneys rising into cold smokeless air. Petrograd in 1917 was already a city of bread lines and food riots; by 1919, cut off from the places that had for hundreds of years supplied it with food and fuel, it was barely surviving on public canteens, the spoils of requisitioning squads, rations, and the black market. It was a starved, brutalized and cynical city.

Two years after the Revolution, did the popular masses of Petrograd still have the ability, or even the desire, to fight for it? The answer to that question will represent a judgement on the Soviet state and the Red Army.

Iudenich

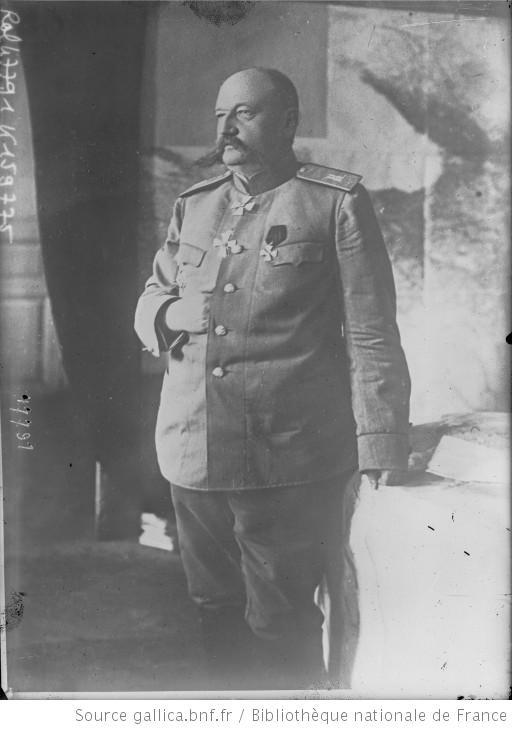

If you’ve read John Reed’s book Ten Days that Shook the World, you will know that a force of Cossacks tried to seize Petrograd in the days following the October Revolution. This was a force of just 700. The attacker in 1919 was a White Army of tens of thousands, led by the war hero General Iudenich.

Right on the doorstep of Petrograd lay the Baltic States, which, first under German occupation and then under British clientship, had served as an incubator for White armies. One White army which mustered in Estonia became known as the North-West Army, an aggregation of officers and reactionaries who swore allegiance to the Tsar. Admiral Kolchak, reigning as Supreme Leader of the White armies in distant Omsk, appointed General Iudenich to command this Baltic army in mid-1919.

Iudenich had conquered a supposedly impregnable mountain fortress from the Turks in the First World War. He had served in the anti-Soviet underground in Petrograd; one wonders how this was feasible given his fame and distinctive appearance (he was a large man with long tusk-like moustaches). He had fled Petrograd in late 1918. Then for the first few months of his command he lived in a hotel in Helsinki with what we can charitably call a government-in-exile – the oil baron Lazonov held three different portfolios, and the ministers were more rivals than colleagues.[i]

Soon after he assumed command, in May 1919, his North-West Army made an initial assault on Soviet territory. There was a spasm of fear in Petrograd. But Iudenich contented himself, for now, with conquering Ingermanland, a sliver of the Russian-Estonian border area.

We learned very little about the Russian Civil War in school, but we did memorise the names of the three White generals – Kolchak, Denikin and Iudenich. The army under Iudenich was not in the same league as the other two – 20,000 fighters to their (roughly) 100,000 each. This was because he had no Cossacks in his neighbourhood and no large population from which to recruit. On the other hand, he had some distinct advantages. The Estonian border is only 130 kilometres from St Petersburg (Dublin to Enniskillen, or London to Coventry) – there were no vast Russian expanses between him and his objective. Of all the White armies his had the shortest lines of supply and communication with the Allies; British naval forces controlled the Baltic and could slip vessels right into Kronstadt harbour. Lastly, if he played his cards right, Iudenich might be able to bring in two neighbouring states on his side.

How to Lose Finns and Alienate Estonians

The Whites and the Finnish and Estonian governments were common enemies of the Soviet regime. Between them, Finland and Estonia could send enough soldiers into Russia to boost Iudenich’s numbers up from 20,000 to 100,000. But the national question was a massive weak spot for the White Russians. They often enraged their potential allies. In Autumn 1919 they would appoint a ‘Governor’ of the Estonian capital city – a city over which they had no control anyway. Iudenich insisted: ‘There is no Estonia. It is a piece of Russian soil, a Russian province. The Estonian government is a gang of criminals who have seized power, and I will enter into no conversations with it.’[ii]

The British mikitary tried to get them to make friends. Brigadier-General Marsh threatened Iudenich: ‘We will throw you aside. We have another commander-in-chief all ready.’

On another occasion Marsh, in person, issued an ultimatum to a gathering of White Russians. He declared that they had 40 minutes to form a democratic government which recognized Finland.[iii] Such measures usually don’t work for parents or teachers (‘I’m going to count to three! One…’) and they didn’t work for a Brigadier-General either. But they show the role which Britain took on itself.

British officers were match-makers, kingmakers, fixers, naval support, and a source of massive supplies of arms and uniforms. They operated a veritable taxi service across the Baltic for various anti-communists to meet up and try to overcome their differences. In spite of everything, Estonia ended up joining the attack on Petrograd – a degree of cooperation which surely would have been impossible without patient British intervention.

Things were no better as regards Finland. In summer 1919 the Finnish government offered the Whites an alliance in exchange for some small territory in Karelia. Iudenich’s superior Kolchak reacted with the words: ‘Fantastic. One would suppose Finland had conquered Russia.’[iv]

In late 1918 and early 1919 the Soviet government supported Estonian and Lithuanian socialists in a series of wars against the British-backed nationalist regimes. But by summer, the Reds had recognised that the potential for a Soviet Baltic was lost for the near future, and they were willing to make a deal with the governments of the Baltic States. For example, on August 8th they offered to recognize Estonia in exchange for the town of Pskov.

Operation White Sword

In summer 1919, General Denikin’s forces conquered southern Russia and swathes of Ukraine, then in the autumn surged north toward Moscow. These victories told Iudenich it was time to make his long-awaited move on Petrograd.[v]

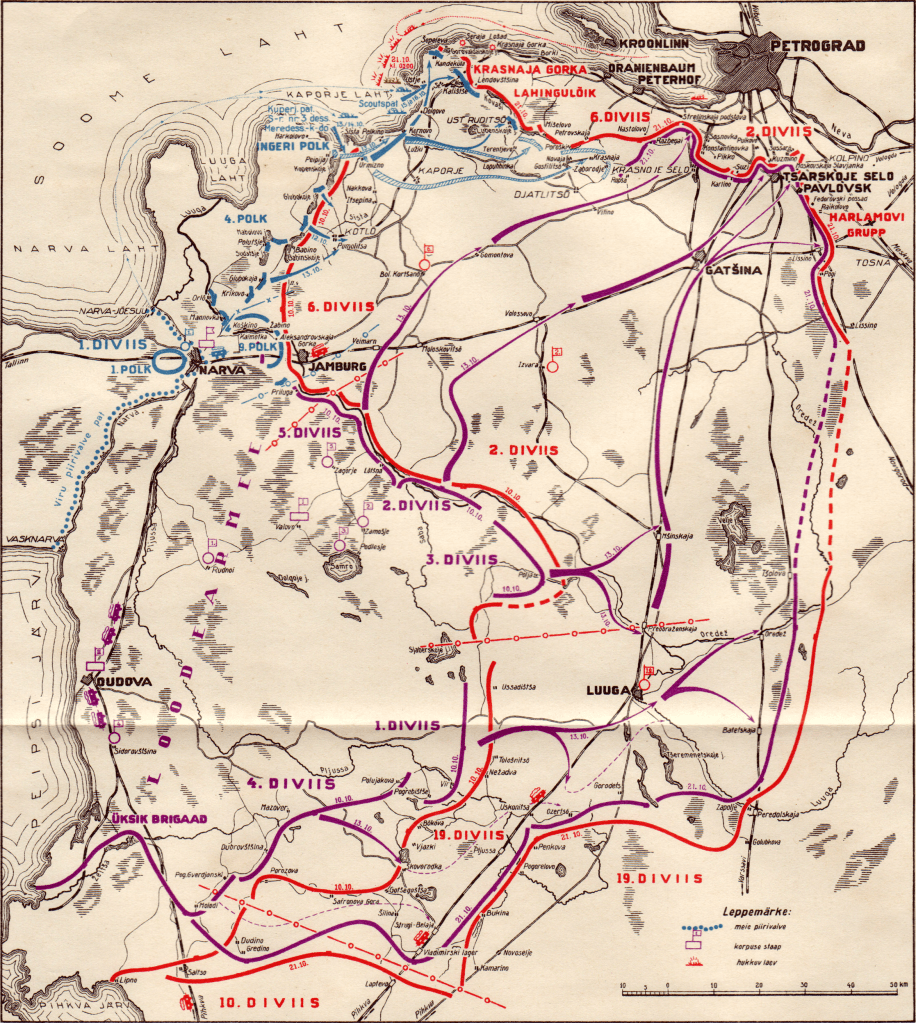

From July British aid began to pour into the hands of Iudenich. And on October 12th, North-West Army began Operation White Sword, a two-pronged advance toward Petrograd. Meanwhile the Estonian Army attacked along the coast and laid siege to the fortress of Krasnaya Gorka. There were 50,000 soldiers in the White Army, with 700 cavalry, four armoured trains, six planes and six tanks.

White Armies always exhibit interesting disproportions, and this one was no exception: one in ten of the 18,500 combat troops were officers, and there were nearly as many generals (53) as there were artillery pieces (57).[vi]

Against this, the Reds were in disarray. Their Baltic Fleet was bottled up in Kronstadt Harbour by the British fleet. The approaches to Petrograd were held by the Red 7th Army. Its 40,000 personnel were not all armed, and had been mostly idle for months. The defeat in Estonia early in the year; the transfer of the best elements to other fronts; and the Liundqvist Affair, in which one of the top officers turned out to be a White spy, all sapped morale. With the onset of the offensive, despair and panic broke out amid the frontline soldiers and soon took hold in Petrograd. 7th Army’s soldiers ran away, dropping their weapons. An entire regiment went over to the Whites.

So great were the early failures of Red Seventh Army that leaders on both sides almost took for granted the fall of Petrograd. The newspapers in the west spent the week reporting that it was imminent. They were not delusionary: in Moscow on October 15th Lenin spoke in favour of surrendering the city. It would be a temporary concession, he argued: the city was home to countless thousands of communists, each one a potential insurgent; let the Whites rest upon it as on a bed of nails.

In early October the pressure on the Southern Front was intense. Whether to defend Petrograd or to let it fall was a decision which, in the words of the Red commander Kamenev, ‘burned in my brain.’ If reinforcements were sent to Petrograd, would there be enough to defend Moscow?

But Trotsky and Stalin both protested against the idea of surrender. Lenin relented, and Stalin took over command of the Southern Front while Trotsky and his armoured train took off for Petrograd.

Trotsky’s Armoured Train

The rail line from Moscow to Petrograd was in danger of being cut off by the inland prong of Iudenich’s advance. So for Trotsky and his staff it must have been an anxious journey.

This was the same train on which the war commissar had arrived at Kazan in August 1918. In the intervening year it had been encased in armour and given three back-up locomotives. Wherever it went, even when it passed a small village, flyers and newspapers rolled off its printing press and Trotsky himself would give a speech. ‘Workers and peasants who listened to him were frequently entranced.’ By the end of 1918 the train had over 300 personnel – it was ‘a full military-political organization.’[vii] It initiated changes at the front, tied the front to the rear and delivered the ‘ideological cement’ which held together the Red Army.[viii]

By war’s end it had visited every front and covered 120,000 kilometres on 36 trips, had been in battle thirteen times and suffered 30 casualties. After the war, the train itself was awarded the Order of the Red Banner [ix] – a whimsical notion, like something out of Thomas the Tank Engine.

The Stone Labyrinth

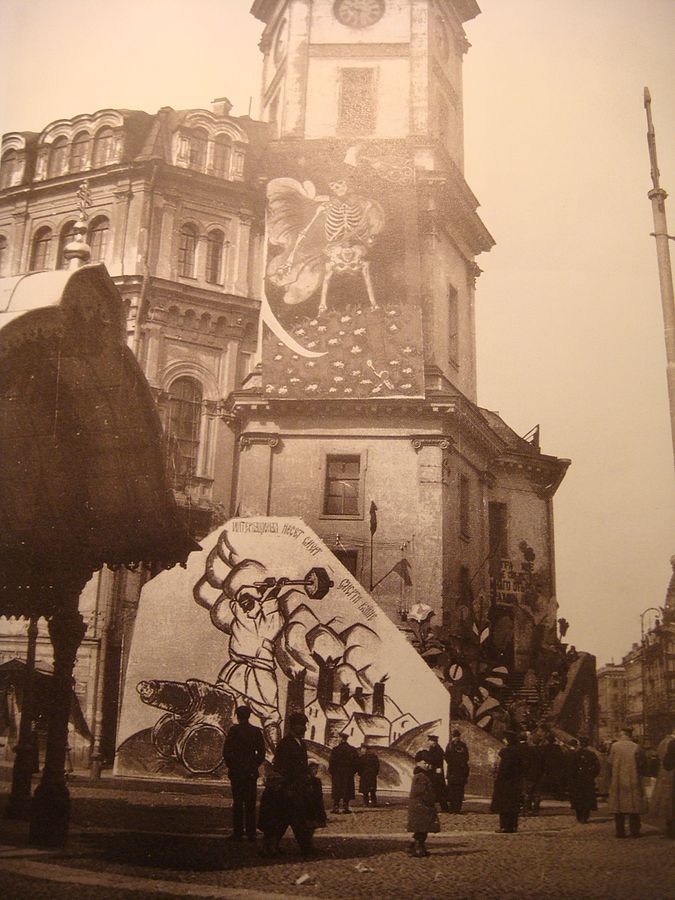

The arrival of Trotsky in Petrograd had an electrifying effect, by all accounts (including his own). Trotsky and his staff shook up the demoralised local officials by force of argument and, where deemed necessary, by sacking and replacing people. The mood changed in the city overnight as the population saw stern measures being taken first of all at the top, while food rations were doubled.

A plan was drawn up to turn the city into a fortress. Trotsky said that it was better if the Whites were defeated outside the city because ‘Street battles do, of course, entail the risk of accidental victims and the destruction of cultural treasures.’[x] But if that should fail, he was prepared for urban warfare in a plan that anticipated Stalingrad. The army of Iudenich would be lost and ground down in the ‘stone labyrinth’ [xi] of hostile streets.

Trotsky was able to mobilise the population to dig trenches, to barricade the streets, and to search, house by house, for White agents. His memoir captures the mood:

The workers of Petrograd looked badly then; their faces were gray from under nourishment; their clothes were in tatters; their shoes, sometimes not even mates, were gaping with holes.

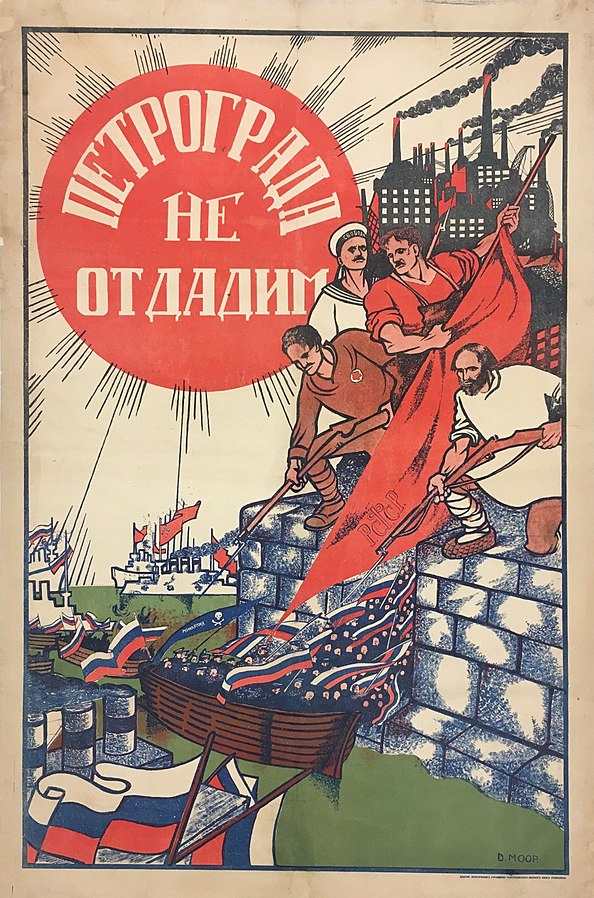

“We will not give up Petrograd, comrades!”

“No.” The eyes of the women burned with especial fervor. Mothers, wives, daughters, were loath to abandon their dingy but warm nests. “No, we won’t give it up,” the high-pitched voices of the women cried in answer, and they grasped their spades like rifles. Not a few of them actually armed themselves with rifles or took their places at the machine-guns.Detachments of men and women, with trenching-tools on their shoulders, filed out of the mills and factories. The workers of Petrograd looked badly then; their faces were gray from under nourishment; their clothes were in tatters; their shoes, sometimes not even mates, were gaping with holes.

“We will not give up Petrograd, comrades!”

“No.” The eyes of the women burned with especial fervor. Mothers, wives, daughters, were loath to abandon their dingy but warm nests. “No, we won’t give it up,” the high-pitched voices of the women cried in answer, and they grasped their spades like rifles. Not a few of them actually armed themselves with rifles or took their places at the machine-guns.

The Bashkirs

Alongside these traditional supporters, Petrograd hosted new and improbable allies. The Bashkir cavalry, the Muslim nomads who had come over to the Reds back in February, happened to be on a visit to the city. We find this description in a novel written by an eyewitness:

They seemed to be happy riding through a town where the horses’ shoes never struck the soil, where all the houses were made of stone… but which was unfortunately lacking in horse troughs. And life must be sad there since there are neither beehives, nor flocks, nor horizons of plains and mountains… their sabres were bedecked with red ribbons. They punctuated their guttural singing with whistle blasts … Kirim always wore a green skullcap embroidered in gold with Arabic letters, even under his huge sheepskin hat. This man was learned in the Koran, Tibetan medicine, and the witchcraft of shamans … He also knew passages of the Communist Manifesto by heart.[xii]

According to western newspapers, pecking at crumbs of rumours in Helsinki, the Bashkirs brought with them a new strain of typhus. Not improbable; the country was riddled with it. Nor is it improbable that this was a racist myth.

The Bashkirs caused a stir in Helsinki for other reasons too. Finland had 25,000 troops facing Petrograd, threatening the prospect of a second front. It must have been a tempting prospect for the White Finns: if they helped take Petrograd they could hold onto some of the territory they would grab in the process. But the White Russians alienated them, and the war hawk Mannerheim was out of power, and there was an anti-war mood among the public. Trotsky had, since September 1st, been making the most of these factors by alternating generous peace proposals with dire threats. In response to any Finnish invasion, he said, the Soviets would unleash a horde of Bashkirs to ‘exterminate’ the bourgeoisie of Finland.[xiii]

The First Soviet Tanks

The Whites made rapid progress toward the city. Early in the campaign the Reds were outnumbered. But throughout the campaign, even later when the scales shifted, the White Guards punched above their weight. They would sneak around Red positions, open fire at them from multiple directions, and set off a stampede of red-star caps and bogatyrkas in the direction of Petrograd.

As at Tsaritsyn, the Whites had only six British tanks. In such small numbers and in this mode of warfare they were of little practical use. But the sight of the crushing treads of these bullet-proof killing machines, or even the rumour of them, terrified the Red soldiers.

In response, the steelworks of Petrograd began to produce the first Soviet tanks. These were not marvels of engineering. Different accounts describe them as almost static, or as tactically useless. But they proved to be a psychological antidote to a psychological threat. The sight of Red ‘tanks’ rolling out of the Putilov works or taking their places in the defensive lines was a source of great encouragement to the Red fighters, who made cheerful puns playing the word ‘Tanka’ and the name ‘Tanya’ against each other.

Seventh Army was heartened by all these changes. ‘The rank-and-file of the Red army got some heartier food, changed their linen and boots, listened to a speech or two, pulled themselves together, and became quite different men,’ writes Trotsky. The Mensheviks put aside their differences with the Bolsheviks and rallied to the defence of the city.

Meanwhile ‘field tribunals did their gruesome work.’[xiv] White organizations – the National Centre and the Union for the Regeneration of Russia – operated underground in the city and the Cheka worked to root them out. Notices would appear bearing lists of ‘COUNTER-REVOLUTIONARIES, SPIES, AND CRIMINALS SHOT.’[xv] The judgments of the Cheka were quick and ruthless.

Could Iudenich take Petrograd?

The historian Mawdsley dismisses the threat posed by Iudenich on the basis that his army was relatively small. Trotsky agreed. In his view, even if the Whites took the city, they would not be able to hold it or to build on their success.

There are grounds to disagree with both Mawdsley and Trotsky on this. In this war, numbers counted for less than morale. In the Caucasus, 20,000 Whites had defeated 150,000 Reds. If panic had been allowed to continue in Petrograd, even a large army would have been unable to hold it.

If Petrograd fell it would later be recaptured, all things being equal. But how could all things possibly stay equal if Petrograd fell? We must consider the moral effect on Red and White soldiers, and beyond Russia. Among the Allies it would give a tremendous boost to the hawks like Churchill. The Finnish government might open a second front, and the Estonian government might commit fully to the war. A White Petrograd would be as open to British shipping as Tallinn or Helsinki. Military and economic aid could pour in just as it had poured into Tallinn.

But the prospect of a White victory was made dimmer by discord behind the lines. In Latvia, a rival White Russian general thought this would be a great moment to try and conquer Riga, the Latvian capital. Not only did this distract the British and the Estonians; the resulting in-fighting, from October 8th, guaranteed that there would be no attack on Russia from the Latvian border, so the entire 15th Red Army, which had been stationed there, now began a slow advance north to join the battle for Petrograd.

The White commanders often let their personal pride get in the way of success. The Latvian diversion is one example; another came when a division commander ignored orders to cut the Moscow-Petrograd railway line because he wanted to be the first into Petrograd.[xvi] This allowed reinforcements from Moscow to bolster the defence.

The Commissar for War Saddles Up

The White advance continued in spite of these challenges. Away in England, Churchill was confident of success, promising a massive consignment of equipment, enough for Iudenich to equip a whole new army, and predicting that there would be ‘lamentable reprisals’ – White Terror – when the city fell.[xvii]

The Reds did not have a cordon or a trench line in front of the city. They had concentrated striking groups which, in theory, were supposed to pounce on less numerous White detachments. But the Reds were on edge. Gatchina was lost on October 17th when some Red cadets came under impressive volleys of fire, took fright, and fled. It turned out to be the work of a single enemy company hiding in the town’s park.

Just the next day Trotsky happened to be in the division headquarters at Aleksandrovsk when a mob of Red soldiers came hurrying past. Winded and panic-stricken men halted to report that an enemy force had appeared on their flank, so they had briefly opened fire then retreated ten kilometres.

The officers at division headquarters consulted their maps and informed the fleeing soldiers that the ‘enemy force’ was actually a Red column. The commander of the fleeing soldiers must have flushed with shame. His battalion had shot at their own friends then fled in terror, leaving a gap which the Whites, at this moment, would be exploiting.

Trotsky took hold of the nearest horse and mounted it in the midst of the hundreds of frightened soldiers. They were at first confused by the spectacle of the war commissar riding around issuing orders to them directly, face to face. They watched him chase down, one by one, all those soldiers who were still retreating, and with stern commands prevail on them to turn around.

A voice was yelling, ‘Courage, boys, Comrade Trotsky is leading you.’

It was Trotsky’s orderly Kozlov, an old soldier from a village in Moscow province. He was running around after Trotsky, waving a revolver in the air and repeating his commands. To a man, the battalion advanced with the war commissar mounted in their midst. After two kilometres, writes Trotsky, ‘the bullets began their sweetish, nauseating whistling, and the first wounded began to drop.’ They did not slacken their pace, but ran quick enough to break a sweat in the late October chill.

Combat was joined. The regimental commander who had taken fright at a friendly unit was, it appears, eager to redeem himself. He went fearlessly into the line of fire and was wounded in both legs. The battalion advanced the remaining eight kilometres under fire until the position it had fled from was ‘thus retaken by some brawny lads from Kaluga, where they drawl their a’s,’ and Trotsky returned to HQ on a lorry, which picked up the wounded as it went.

Serge imagines the War Commissar as, seated in the truck, he ‘wiped the sweat off his brow. Ouf! He had almost lost his pince-nez.’[xviii]

But in spite of feats like this, the frontlines closed in on the outskirts of the city. The Whites could see in the distance the sunlight on the golden dome of St Isaac’s cathedral in the middle of Petrograd, and they boasted that they would be marching down the Nevsky Prospekt in the coming days.

But as the fighting came closer and closer to Petrograd, the resistance grew tougher. At the Pulkovo Heights south of town the Red frontline at last began to hold. The British had sunk the warship Sevastopol in a raid on Kronstadt Harbour months before; somehow the Reds raised it up and restored its guns to working order. Along with all the naval artillery concentrated in Kronstadt, the guns of the Sevastopol pointed inland and let loose terrible volleys on the Whites.

Cadets from the training schools were rushed to the frontlines. The coastal fort of Krasnaya Gorka had defeated the Estonian advance along the shore, so 11,000 Kronstadt sailors were freed up to join the defense of Petrograd.[xix]

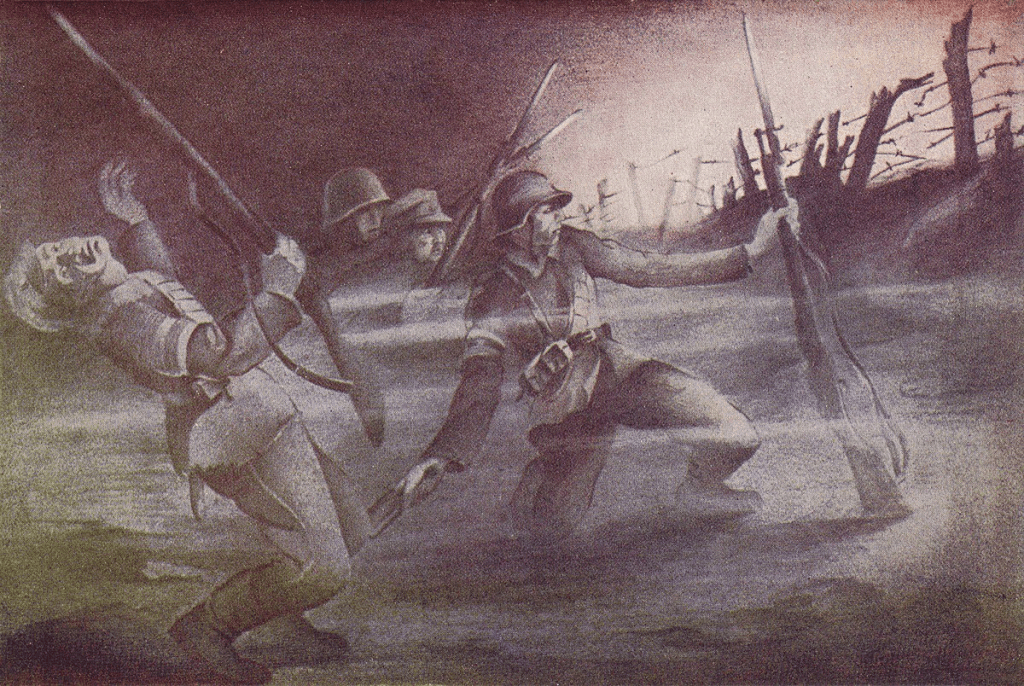

Pulkovo Heights

The Whites were given an order to capture the Pulkovo Heights, a rise just south of the city, on the night of October 20th-21st. But at 11pm the Reds went on the attack, jumping the gun. High-explosive shells manufactured in Britain or France exploded over the heads of Bashkir cavalry, of young peasant conscripts in khaki, of sailors in black. The sailors and worker-volunteers ‘fought like lions.’ They charged at tanks with bayonets and revolvers.[xx] The attackers took heart when the makeshift Red tanks joined the battle: ‘The Red troops greeted with delight the appearance of the first armoured caterpillar.’[xxi]

The Whites were at the end of their supply lines and, in the words of Isaac Deutscher, the power of the Red Army was like a compressed spring ready for the recoil.[xxii] The Reds no longer had any space behind them into which to retreat. Supplies and communications, for once, ran smoothly thanks to the proximity of Petrograd and its supplies, infrastructure and volunteers. But the Whites were determined and brave, and Iudenich brought up reserves to bolster them. On October 22nd the Whites held firm in a day of terrible fighting.

The Reds now had a massive superiority in numbers. Morale was transformed from a few days before: units tried to out-perform one another. The sailors were ‘splendid’ because they knew the Whites would take no prisoners from among them.[xxiii] Trotsky’s train crew was in the thick of the fighting in these days: three were killed, six wounded, and three shell-shocked.

On October 23rd the Reds recaptured the key suburb of Tsarskoe Selo. Meanwhile 15th Army – the army which had been freed from the Latvian border thanks to White in-fighting – was advancing slowly into the deep rear of the Whites. White soldiers began surrendering by the dozen.

Red Initiative

The Whites began a fighting retreat, and the Red Army pursued.

Trotsky’s orders contained humanistic messages. Enemies who surrendered must be spared – ‘woe to the unworthy soldier’ who hurts a prisoner. ‘Only a tiny minority’ of the Whites, both officers and enlisted soldiers, are determined enemies, argued an order of October 24th. On the same day, an order urged ‘Red warriors’ to draw a distinction between the British government and the British working people.[xxiv] A later order (No 164) says that peasants conscripted by the enemy will be paid, given horses and allowed to keep their uniforms if only they hand over their rifles.

Draconian tones reassert themselves in italics in an order of October 30th (No 163), a sign that the White retreat was a controlled one and that the fighting was still formidable: ‘anyone who tries to start a panic, calling on our men to throw down their arms and go over to the Whites, is to be killed on the spot.’

Iudenich fought hard until November 3rd, then began a general retreat toward the Estonian border. Trotsky was for sending the Red Army after them into Estonia. But Chicherin and Lenin argued against this, and prevailed.

When the forces of Iudenich reached the border, the Estonians first denied them entry then let them in, disarming and imprisoning them. The White army was already afflicted by typhus, and in prison conditions it only got worse. The Estonian government fed them only on lampreys and forced them to cut down trees through the Baltic winter. It is estimated that 10,000 perished [xxv] – if so, the Estonians killed more of them than the Reds.

Before the end of the year, Estonia and Soviet Russia had signed an armistice, and a peace treaty soon followed. Over the next year the Soviet Union sealed peace treaties with Latvia and Lithuania as well.

The Battle of Petrograd was a judgment on two years of Soviet power. Looking at the depressed and almost lifeless city in autumn 1919, you’d be forgiven for thinking that there was nothing left of the spirit of revolution. But thousands of the city’s workers fought or participated in the battle. Early on, the Red Army was prone to humiliating attacks of panic – but strong leadership, tight supply lines and an urgent threat brought out its strengths in the end, and once the initiative passed to their side these strengths proved overwhelming.

In this post we have seen the working class of the young Soviet Republic and its army tested on the relatively small scale of one city. During those weeks, Central Russia went through a trial that was bigger in scale to the point where it was qualitatively different. That will be the subject of the next episode – the final chapter of this second series of Revolution Under Siege and the decisive chapter of the whole story.

Go to Revolution Under Siege Archive

Memoirs of Trotsky: https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1930/mylife/ch35.htm#:~:text=%E2%80%9CTo%20defend%20Petrograd%20to%20the,extinction%20if%20it%20met%20serious

[i] Smele, Jonathan, The ‘Russian’ Civil Wars, Hurst & Company, London, 2015, p 128

[ii] Kinvig, Clifford, Churchill’s Crusade, Hambledon, 2006, p 272

[iii] Kinvig, 275-6

[iv] Kinvig, 273

[v] Churchill believed that Iudenich could take Petrograd, so much so that he had moved on to second-order concerns: earlier in the year he had communicated to Iudenich his concern that the conquest of Petrograd would turn into one massive pogrom: ‘Excesses by anti-Bolsheviks if they are victorious will alienate sympathy British nation [sic] and render continuance of support most difficult’ (Kinvig, 274)

[vi] Smele, 129

[vii] Service, Robert, Trotsky, Belknap Press, 2009, p 230-231

[viii] Smele, 132

[ix] Smele, 132,3

[x] Trotsky, How the Revolution Armed, ‘Petrograd Will Defend Itself From Within As Well’ https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1919/military/ch135.htm

[xi] Mawdsley, p 276

[xii] Serge, Victor, Conquered City, 1932, trans Richard Greeman, New York Review of Books, 2011, p 169-170

[xiii] Trotsky, How the Revolution Armed, https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1919/military/ch134.htm

[xiv] Kinvig, p 284

[xv] Serge, Conquered City, p 189

[xvi] Beevor, Antony, Russia, Orion, 2023, p 365

[xvii] Beevor, 366

[xviii] Serge, Conquered City, p 186

[xix] Serge, Conquered City, p 124

[xx] By some accounts the tanks were not present at this decisive struggle.

[xxi] Trotsky, How the Revolution Armed, ‘The Turning Point’ https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1919/military/ch141.htm

[xxii] Deutscher, The Prophet Armed, 1954, Verso Books, 2003, 365

[xxiii] Serge, Conquered City, 185-6

[xxiv] The Soviet Union had suffered thousands of deaths from the weapons of the British navy and millions of deaths from a British blockade, and was at that moment fighting against three armies in British uniforms and with British rifles, and furthermore had, on the night of October 21st, lost three destroyers with all hands to British mines; but Order No. 159 ended with the words: ‘Death to the vultures of imperialism! Long live workers’ Britain, the Britain of Labour, of the people!’ All references to Volume II of How the Revolution Armed.

[xxv] Kinvig, 286

3 thoughts on “20: The Battle of Petrograd”