When I was ten, eleven, twelve years old, a lot of adults were worried that games like Grand Theft Auto 3 would warp our young minds and turn us violent. But for me, while GTA was fun, the violence was so obviously out-there, so outrageous, I didn’t have any trouble distinguishing between it and reality.

GTA was set on normal city streets. The props were cars and pedestrians and buildings. But you were stealing a car, running people over and shooting down police helicopters. The familiar and normal environment acted as a foil to the crazy violence. You could walk home from your friend’s house after playing GTA and you knew that this was the real world in front of you, and that it didn’t operate by the same rules. There’s a car; but you can’t run up to it, press Triangle to break in and hotwire it, and accelerate.

What about a game with a more exotic setting? What about a game set in an alternate-history version of the Cold War? You’re young. You haven’t covered this in school, or read any books about it. Command and Conquer: Red Alert 2 is your first encounter with the Soviet Union. You know it’s a videogame, it’s at least to some extent fantasy, but you have no real-life counterpart to measure it up against.

Looking back after having read a lot and written a bit, I have a new perspective on Red Alert 2 (like a few months back when I revisited Orwell, except that in my age group, Red Alert probably had more influence than 1984). If we’re going to talk about warping minds, forget GTA. Here is a game that planted deep in my brain a funhouse-mirror perspective on history and geopolitics. Red Alert 2 is just extraordinary.

On the face of it, this might seem to be a finicky post where I nit-pick a fun game and lecture everyone about history. But really I have a secret agenda here. I’m writing this so that I have an excuse to talk length about a game from the early ‘000s about which I am incurably nostalgic to this day.

Sidebar: For those who don’t know, Command & Conquer: Red Alert 2 was a strategy game released in 2000 by Westwood Studios. The story, implausible at literally every turn, revolves around the Cold War, time travel and alternate histories. And it starts with the classic alternate history: in 1996’s Red Alert, Einstein invents time travel and goes back to the 1920s to kill Hitler. But he returns to a present where Stalin is conquering Europe in Hitler’s place (yes, an implicit endorsement of Hitler. And no, they never address this). In 2000’s Red Alert 2, the Soviets have another go at world conquest, launching a sudden surprise attack on the US. In Red Alert 3, the once-again defeated Soviets make their own time machine, but by defeating America they inadvertently end up creating a timeline where Japan is challenging them for world domination. In terms of tone, Red Alert tries to keep a straight face, and Red Alert 3 fully takes the piss. 2 is in the middle, ie, tongue-in-cheek.

Red Alert 2 is a good game, for its time. It’s easy to pick up and play, but there is a certain versatility and depth in the range of units. The fact that the environments are just slightly interactive – put guys in buildings, blow up bridges – goes a long way. The colours are bright, the unit models visually distinct and full of character. The fast food restaurant is called ‘McBurger Kong.’ The campaigns hold up well for variety, challenge and playability. The score, composed by Frank Klepacki, is part industrial, part funk, part Red Army Choir, all brilliant.

But the real strength of this game is its attitude. Unlike its predecessor Tiberian Sun, which is on paper a very similar game, Red Alert 2 doesn’t take itself seriously. To everything bad I’m going to say about it here, Red Alert 2 can mostly get away with shrugging its shoulders, grinning and claiming that it was only joking.

The sexism in the live-action cut-scenes – all that creepy pandering to 13-year-old boys – was obvious to me even at the time, and I don’t think there’s much to dissect. It’s right there.

Instead, let’s talk about Iraqi desolators, Libyan demolition trucks and Cuban terrorists.

There goes the neighbourhood!

In the game’s skirmish mode, the player can choose from a list of countries. One of the playable countries in the Soviet bloc is Iraq. Sure – Iraq is communist. Why not. The Iraqi soldiers are identical to the Soviet soldiers, right down to the cartoon Slavic accent. The only difference is that each country gets a special unit; in the case of Iraq, you get the Desolator. This charming little fellow shoots a green beam of radiation at people, zapping them instantly into writhing emerald goo. He also has a special move, where he contaminates a massive area around him, turning it green and killing everyone on it.

Years later I would learn that it was the United States which used depleted uranium munitions in Iraq (before and after this game was released) leading to cancers and birth defects. A few years after this game was made, the US would invade Iraq based on the lie that the country had chemical and nuclear weapons. When the Desolator shouts his cheeky catchphrase before turning the land around him a lethal green, it’s a little cultural artefact of this big lie, a lie which in real life covered a whole country in that green shroud and caused incalculable suffering for the Iraqi people. In real life, the US unleashed desolation on Iraq. In this game, it’s the other way around.

Vamos, Muchachos!

The various countries in the Soviet Bloc have one thing in common: they are all countries that were at odds with the United States in the late 1990s. So we’ve got Libya and Cuba in there as well. The Libyans have a Demolition Truck – ‘One way trip!’ – which blows itself up in a small nuclear explosion; the Cubans have a little guy called a Terrorist – ‘Vamos, muchachos!’ – who blows himself up along with anyone near him.

But it was Cuba that was targeted by terrorists funded and encouraged by the United States, not the other way around. Cuban suicide bombing is not and has never been a thing.

The Libya thing, in hindsight, just makes me sad, especially with the most recent disaster. Unlike with Iraq, I don’t even have anything slightly clever to say. Libya was once the country with the highest standard of living in all of Africa. Then came the US-backed overthrow of Gaddafi in 2011. They dragged him out of a ditch and killed him in a most brutal manner, and the remarks made for the occasion by then-Secretary of State Hilary Clinton (‘we came, we saw, he died’) make the bombastically cruel Soviet leaders in this videogame seem like sensitive souls by comparison. Since then Libya has been transformed into a conflict-ridden country. The EU gives them tons of money to lock up refugees in desperate conditions, just to appease the racists back home.

The Desolator and the Terrorist have one important thing in common: they are tiny cultural artefacts of imperial projection. What do I mean by projection? I’ll put it this way: if Westwood had decided to include Vietnam as a playable country, they would have been depicted burning down American homesteads with napalm, or withering the forests with Agent Orange. In the pop culture of the imperialist aggressor, its own historic crimes are pinned on its victims.

9/11

Adam Curtis’ documentary HyperNormalisation (01:39:35-01:43:00) includes a remarkable montage of scenes from movies that look exactly like footage from 9/11 – only these movies were all made before 9/11. Someone tell Adam Curtis about Red Alert 2. Released just a year before 9/11, the game’s advertising featured the twin towers prominently, meanced by, among other things, aeroplanes. The first mission in the Soviet campaign involves destroying the Pentagon, and a couple of missions later you are in New York, where you can occupy or destroy the World Trade Centre. The zeitgeist which Curtis identifies in HyperNormalisation is perfectly captured in Red Alert 2.

Coalition of the Willing V Axis of Evil

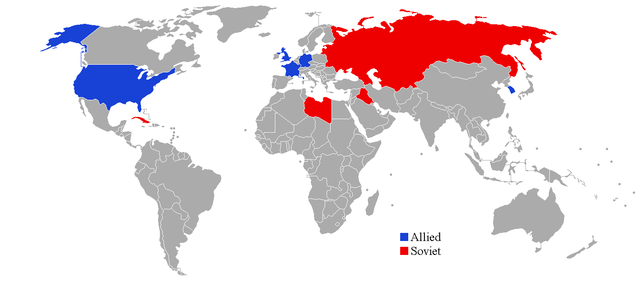

The USSR’s three playable allies are Iraq, Cuba and Libya, while the USA’s equivalent are Korea, Britain, Germany and France (see the map below from Wikimedia Commons). With the exception of Korea (reunified offscreen), this world war sees Africa, the Middle East and Latin America take on Europe and North America. It’s the former colonies against the colonisers (a massive piece of historical context which was missing from my 11-year-old head). It’s a fantasy where what really happened is reversed, ie, the masses of Africa, Asia and Latin America commit atrocities in the USA, a contrived scenario to justify the colonisers getting to slaughter the peoples of the colonies all over again.

Simply reversing the projection, of course, wouldn’t accurately reflect the Cold War. Why not include the Afghan Mujahideen among the ‘Allies’? What would their special unit be? Where is Nelson Mandela in the pro-USSR coalition?

Your command is my wish

This imperial projection is most obvious with an unforgettable character named Yuri (The Soviets are a surprisingly informal bunch. Top brass are simply addressed as Yuri, Vladimir and Natasha – no surnames, no patronymics). Yuri employs psychic powers and elaborate machines to control people’s minds. This is a developed part of the world and story, with mind-controlled communist giant squids terrorising the high seas and a US president taken over by a psychic beacon. Yuri’s acolytes are developed into a colourful and horrifying faction in their own right in the expansion, Yuri’s Revenge, which takes the irony up a few notches and gets the Allies and Soviets to join forces and have a joint moon landing.

Ten thousand volts, coming up!

Tesla, now the name of a company which is a bastion of US capitalism, features in Red Alert 2 as an alternative energy source favoured by the Soviets. We see the Soviets weaponise Tesla energy through ‘Tesla Coils’ and ‘Tesla Troopers’ who electrocute people and even turn the Eiffel Tower into a kind of pylon.

All this hits you differently after you’ve read about MKUltra, or The Shock Doctrine by Naomi Klein. Mind control experiments were actually the preserve of the United States. The fact that US prisoners in Korea were subjected to lectures aimed at recruiting them to the communist cause was interpreted by a hysterical US media and political class as ‘mind control.’ But the interest of US state forces such as the CIA was piqued; they experimented with electric shock therapy and LSD. These experiments failed to produce mind control, but left people dead or severely brain damaged.

In this game, the Soviets have nukes; the Americans do not. The Soviet nuclear reactor is a nod to the Chernobyl disaster – here we’re dealing with something from actual history, so okay. The Soviets had nuclear weapons, and tested them in very harmful and irresponsible ways. But the Allies did those things too, and also killed a quarter of a million innocent people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. More projection.

Sometimes the cold war stereotyping is so obvious and crass it goes beyond offensive, and sometimes it flies under the radar because it’s larded in a protective wrapping of irony. Other times it is just bigoted, plain and simple. For example, there is another colourful unit type called Crazy Ivan, who cackles maniacally as he plants bombs on things. You don’t have to be a raving tankie to see the problem with this.

Jusht give me a plan

But it’s satire, right? Surely they make just as much fun of the Americans? No, not at all. General Carville has a bit of a hillbilly affect (‘his forces are rompin’ through the country like an angry bull at a Texas rodeo’). The Spy talks like a caricature of Sean Connery. But that’s as far as it goes.

The contrast is clear even if you never watch the cutscenes. The Soviets use nuclear and chemical weapons, electric shocks, cartoon dynamite, human cloning and mind control – evil, in other words. Meanwhile the Allies use high technology: weather control, time travel, jetpacks, and tanks that can disguise themselves as trees. The Soviets have things that are excessive, ugly and brutal, while the Allies have things that are ingenious, streamlined and attractive. In short: the Soviets have giant squids and the Allies have dolphins.

Mind forg’d manacles

Maybe this is the only blog on the internet where you’ll find references to Milton and Blake employed to analyse Westwood Studios and Red Alert 2. But here goes: in a note in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1793), William Blake made a famous observation about John Milton’s biblical epic Paradise Lost (1667): “The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels and God, and at liberty when of Devils and Hell, is because he was a true poet and of the Devils’ party without knowing it.” The Soviets in Red Alert 2 (2000) are clearly “the Devils’ party.” But they are so much more interesting and fun than the Allies. The developers and the players are of their party without knowing it.

Part of this is that the audience in Western Europe and North America has some sympathy for the ‘devil.’ As the losers of the Cold War and as a vanished social system, they hold some fascination; it’s obvious even to an 11 year old who knows no history that they are being caricatured and demonised, which excites some grudging sympathy; meanwhile, they are yesterday’s enemy, not threatening today.

The other part is projection. Yes, we’re back to projection. The audience in Western Europe and North America identifies with the ‘evil’ side because it knows, deep down, that neither side in the Cold War had a monopoly on evil. All the napalm and all the massacres, the coups and torture sites, the mountains bombed into valleys and the cities wiped off the map, the psychotic warlords and fascist dictators with American weapons in their hands – these things rarely feature in popular culture. But they are the means by which capitalism won the Cold War. Our governments and corporations inflicted unspeakable horrors on Africa, Asia and Latin America in the recent past. In Red Alert 2, we assign all that evil to the other side of the Cold War. And the West European or North American player delights in the extravagant, cartoon evil of the Soviets because, subconsciously, he sees in them the state and social system with which he identifies.

But the most remarkable thing about Red Alert 2 is not how it looked back at the Cold War, but how it looked forward, with what I can only describe as prescient hypocrisy, to the so-called ‘War on Terror.’ It was part of a chorus of pop culture texts fantasizing about an attack on Manhattan just before it happened; and it singled out Iraq and Libya, whom the US would soon target for ‘regime change,’ doing far more damage to those countries than the imaginary Soviet assault does on the United States.

So, do videogames warp young minds?

When you learn something new, you fit it in with what you already knew. And for my generation ‘what we already knew’ about the Cold War consisted of stuff like James Bond and Red Alert 2: crude pop culture propaganda.

As opposed to an intentional propaganda message, Red Alert 2 is a text in which there are assumptions baked in which transmit propaganda messages. But the game’s pure silliness defuses the propaganda, ridicules what it is transmitting, takes most of the sting out of it. If this game really did warp my mind, it was not that difficult to un-warp it again. In its anticommunism and Russophobia it was no worse than a lot of the books on the market, and a lot of the messaging in schools, at the time or today. This underlines another point about warped minds: it takes a whole culture, not just a single text, to change the way a person sees the world. In contrast to the broader culture, Red Alert 2 has this redeeming feature: that it is well aware of its own silliness.

2 thoughts on “Games that warped my young mind: Red Alert 2”