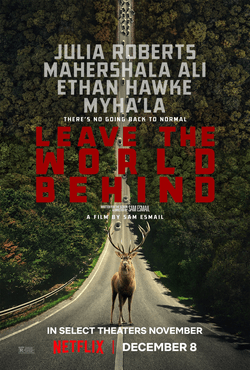

This is a review of the 2023 Netflix movie Leave the World Behind (dir. Sam Esmail). Rather than review it myself, I have delegated the job to a time-traveler from the early Soviet Union. If he does a good job, I will delegate other reviews in the future to other time travelers – 7th-century monks figuring out crime thrillers, eighteenth-century rakes getting teary-eyed over Pixar cartoons, 24th-century asteroid-croppers watching rom coms...

I have spent only a few days in the 21st Century. I have barely ventured outside, as I find this world disorienting and distressing. My host suggested watching a film set in this current century to help orientate me. So I watched the most prominently-advertised film on his home cinema screen: Leave the World Behind.

In this film a family of the intelligentsia leaves the capital for a few days to rent a dacha in the countryside. But their social order begins collapsing around their ears. First, communications and transport are cut. Next, the country is flooded with disorienting enemy propaganda. Last, civil war breaks out. The same thing happened to us in 1918 only, as with everything in Russia, it took longer. They are under attack from an unknown enemy – and speaking from my own bitter experience, it’s probably the Czechoslovak Legion in league with the Cossacks, backed by the Anglo-French imperialist bandits.

The owner of the dacha flees from a calamity in the city along with his daughter, and they arrive at the dacha seeking shelter. He is bourgeois, and he is the owner of the house, but he is also a member of an oppressed nationality. So the mother of the intelligentsia family treats him with chauvinistic suspicion and contempt.

So far, the film presents a situation I can easily comprehend. The characters, too, were familiar types to me.

The father has a fine head of greying hair and a small beard. He is professor, and he looks not unlike some of my own old professors. I recognised him at once as a Narodnik, as he is generous and feckless, democratic in his opinions but not always democratic in his instincts. As the film went on I was again and again confirmed in my impression.

They have a young daughter who is obsessed with fictional works composed several decades before she was born. Naturally, I am unfamiliar with the works in question (Friends and The West Wing), but I felt sympathy with this character as I spent much of my youth engrossed in Turgenev and Tolstoy.

The intellectual family also have a son, a worthless fellow who is cruel to his sister. Late in the film, his teeth fall out of his head. It appears to be a side-effect of some epidemic – again, this to me is very familiar. So the boy and the two men go to a local kulak, who has been hoarding medical supplies. But in this crisis the rural population has turned inward, and the wealthier peasants are solely concerned with individual property and family. The kulak refuses to accept their worthless paper money, and threatens them with a rifle. I could have warned them this would happen.

The bourgeois draws a pistol, intending to expropriate the kulak’s medical supplies by force, but the intellectual becomes histrionic, bares his chest to both firearms, and throws himself on the kulak’s mercy.

The wily peasant relents and accepts the paper money, saying that a ‘barter system’ is acceptable to him.

There was much I did not understand in this film, but I gave a hearty and appreciative laugh when the intellectual salvaged a little of his dignity by correcting the kulak: ‘Well, I gave you money, so it’s not really barter.’

Stripped of their collectivity, these individuals and family groups still respond to their class instincts but lack any actual power. They flounder and tread water. They are saved only by a happy accident; the local landlord has abandoned his mansion, taking his family and all his servants with him, leaving a well-appointed cellar stocked with supplies and cultural riches, which the intelligent young girl finds. The only danger is that the adults will find the nobleman’s wine cellar and drink themselves into oblivion.

They will take refuge from the coming civil war in a nobleman’s cellar. Well and good for them. But what about the fate of their nation and people? To this they appear completely indifferent.

To myself, a man out of time, much was strange, much was familiar. These people of 2023 have screens instead of newspapers; that much is easy enough to grasp. The only printed material in the film is a leaflet in Arabic dropped by some Basmachi aviator. People still smoke, but their pipes are made of metal. With regard to motor cars, it appears the rabid anti-Semite and union-buster Ford has been long since put out of business by Monsieur Tesla’s company.

My host expected me to be awed by the technology. But I expected more from the 21st Century than handheld screens and motor cars which drive themselves (very poorly). At one point wee see that there is a tattered-looking American flag on the moon. That’s it! Only a flag. The relations between men and women appear to be less unequal than in my own time, but aside from that I was, I confess, disappointed by how readily I felt I could comprehend the social relations on screen.