‘Ideas which enter the mind under fire remain there securely and forever.’

- Lev Trotsky, quoted in Trudell, Megan, The Russian Civil War: A Marxist Analysis, International Socialism, Spring 2000

This is the Conclusion to Revolution Under Siege, a series about the Russian Civil War. In this first part of the Conclusion, we will ask: How did the Red Army win the war? What was the nature of Allied intervention? Were the White Guards fascist?

How the Red Army triumphed

The Soviet victory in the Russian Civil War has been summed up in all kinds of dramatic ways: ‘A People’s Tragedy’ or ‘the Death of Hope’ (no less!). Whatever picture you have of the Civil War in your own mind, the vanishing point, ‘the place where all the rays meet’ (as Tolstoy is supposed to have said) is October. If the October Revolution was legitimate and justified, then the struggle to defend it was inspiring. If the Revolution was a coup by conspirators bent on mass murder and insane social experiments, then each battle to defend it was just one more atrocity.

But since I am switching from narrative mode to conclusion mode, let’s not agree to disagree. The Allied intervention forces at first believed that the Bolsheviks were an isolated group who were out of their depth. If this had been true, the Whites would have had little difficulty in winning the war. If October really was an undemocratic coup, if the political programme of Lenin and Trotsky was a wild social experiment, then the outcome of the Civil War would make no sense.

The fact that the Reds controlled the part of Russia with the largest population, best transport links, most industry and largest military stockpiles was an important reason for their victory. But this fact was not an accident. The Whites and Reds did not draw cards at random for territory. In this logistically ‘central’ and majority working-class area of Russia, the Bolsheviks received large majority votes not only in the Soviet but in the Constituent Assembly elections.

Their support among the working class was very strong, and remained very strong through incredible hardships. Working from this powerful base, the Soviet regime drew into its orbit large swathes of the farming population along with the national minorities. Hence it was able to build an army which vastly outnumbered that of the Whites.

In 1918-9 the Whites secured base areas and foreign aid, and built large armies. If the Soviet leaders were only adventurers, and if the Red Army was only a mass of conscripts subjected to terror and crude propaganda, Kolchak and Denikin would have steamrolled them. But the Soviets’ internal collapse, on which every White general counted, never took place.

Western historians have approached this war in the footsteps of the interventionists of their own country. Like their grandads, they refer to the Red Army as ‘the Bolsheviks’ as if to fool themselves into thinking that they are only speaking about a crew of cranks. But they often come away with a wary respect for the Soviets:

‘Yet these despised creatures [the ‘Bolsheviks’], these subhumans, who according to the casualty figures were all but annihilated time and again in various sectors – for some unaccountable reason continued to appear in strength. Not only that; they fought back hard, and as time went by they developed an unmistakable military prowess…’ [1]

The interventionists and the Whites had to learn this wary respect too, but the hard way.

There is a perception that the Reds won through violence and propaganda. [2] But the Whites were not shy when it came to violence and, because many of them were military officers, they were much better at it. When the Civil War broke out, the Soviets had only very feeble military and security institutions. Besides, violence often backfired, as in the Don country in early 1919.

They did manage to turn a movement of factory militias into an army – under-supplied, wearing a motley collection of uniforms and with barely a single steel helmet between the five million of them; and leaking deserters like a sieve, especially at harvest time – but nonetheless an army capable of winning this war. 50,000-70,000 women served in it. It had no officers, no ranks – ‘company commander’, for example, was a job title held by a qualified soldier who wore the same uniform as the rank-and-file soldier. Corporal punishment was banned. The army was truly multinational in character: primarily Russian, Ukrainian and Belarussian, but also Finnish, Latvian, Chinese, Hungarian, Uzbek… Among them was the Senegalese Kador Ben-Salim, who came to Russia with a travelling circus, joined the Red Army, and later became a Soviet movie star. Education and political discussion were central in this new type of army – and they were sorely needed, since even many commanders had only three years of schooling and didn’t know arithmetic. But ‘by the end of 1920 there were 3,000 Red Army schools, 60 amateur theatres, and libraries with reading rooms in every soldiers’ club.’ [3]

Yes, the Reds were good at inflicting violence – in the sense that they were able to build a cohesive and large military force using democratic and socialist methods.

As for propaganda, the Whites had no qualms about churning out lurid anti-Semitic propaganda posters and forgeries like the ‘Zunder Document’ and the ‘Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion.’ But the Reds probably had more industrial printing facilities and paper stocks at their disposal. More importantly, they had an appealing political programme which enthused both the artists who created the propaganda and the people who consumed it. This propaganda had the great benefit of usually being positive and sincere.

So in these limited senses, it was true that violence and propaganda were important.

But crucial to the Red victory were the innate qualities of the working class of the former Russian Empire: their capacity for self-sacrifice; their creative and technical skills; their courage and resourcefulness, for example in organizing a partisan movement in Siberia. Their social skills and political sophistication made a huge difference – they found ways to work with specialists from the former privileged classes, without handing power back to them; ways to neutralize or win over enemies like the Cossacks; ways to fraternize with interventionist troops such as the French and the Germans; ways to make friends of national groups who had been foes, such as the Bashkirs. On top of these innate qualities, they learned quickly and we can see the Red Army growing from a partisan and militia movement to an army with systematic workings. Ideas learned under fire, as Trotsky remarked, are learned for good.

These qualities would not have found expression without the channel provided by the programme and method of the Bolshevik Party. Without the latter leading the Soviets to power in October 1917, this revolutionary energy would have dissipated. But the Bolshevik Party itself would not have existed without a working-class support base and cadre. It was a product of its class.

Were the Whites fascist?

The leading cadre of the Whites also showed courage, resourcefulness, endurance, military skill and valour. But by contrast with the Reds, the White movement was anti-democratic and unpopular. The White leaders openly despised the popular masses. Their contempt for ‘politics’ was in fact contempt for the burning demands of the people – silly political questions like land can be settled after the important business of flogging and hanging the revolutionaries.

Their harshness, fury and inclination to violence werr no surprise. They were gestated in the Tsarist military, an institution which was far harsher and more hierarchical than its peers in other European countries.

General Sakharov, a right-hand man of Kolchak, refused to serve in a particular military unit because it was associated with the ‘democratic spirit’ of the Komuch government. [4] Other White leaders challenged one another to duels or even assassinated one another over accusations of pandering to ‘the democracy.’ The White leaders never accepted the Constituent Assembly results, which they dismissed as popular madness and anarchy.

‘[They] aspired to re-establish ‘Russia One and Indivisible’, which meant suppressing ‘anarchy’ and restoring a strong state and the values of the Orthodox Church. What united them emotionally was a passionate detestation of Bolshevism, which they saw as a ‘German-Jewish’ conspiracy […] In White propaganda, the words ‘Jew’ (zhid) and ‘Communist’ were interchangeable. Naturally, they detested class conflict, and they feared and hated the revolutionary masses (that ‘wild beast’ […].’ [5]

The partner of the White officer was the Cossack. The Cossack, in contrast to the officer, was often mobilised by a popular demand for the autonomy of his particular host. Other motivating factors were a fear of the ‘aliens,’ their tenants; the desire of wealthier Cossacks to hold onto power; and the Cossack tradition of military service. The Cossacks were indispensable to the White war effort, and tens of thousands of them stuck out the Civil War to the end. But by mid-1920, Wrangel found that the Don and Kuban Cossacks did not have another rebellion in them. They too had learned certain ideas under fire.

Only episodically, and with disappointing results, did the Whites attempt to mobilize the population at large. In the words of Mawdsley, ‘their social and political programme was not one that bred spontaneous popular support.’

Many White leaders later embraced fascism. Around the time Mussolini marched on Rome, Sakharov claimed with pride that ‘the White movement was in essence the first manifestation of fascism.’ But Mawdsley scorns this claim – because ‘the Whites lacked the mobilization skills and relatively wide social base of the Italian or German radical Right’ [6].

Just to underline that point: the best argument for regarding them as not fascist is simply that they couldn’t mobilise mass support – not that they weren’t reactionary, or that they weren’t violent. To quote The Simpsons (and to paraphrase Mawdsley), they were never popular.

The Whites were a movement of the middle and upper classes which was pulled together over the course of the year 1917. Its origins lay soon after the February Revolution, when Denikin, Kornilov and their milieu reached a firm decision: in the words of Denikin’s memoirs, ‘Military power must be seized.’ The Kornilov Affair was the first attempt. After the October Revolution the same people created the White Armies, to fight the Soviet regime openly. They embarked on a civil war without popular support, in fact consciously ranging themselves against the will of the population. At first (October 1917 to April 1918) they failed miserably, though in the process they caused much destruction and suffering. Their failure (and the initial failures of Dutov, Semyonov etc) was due to the fact that massive numbers of workers and poor peasants mobilised against them whenever they raised their heads. But from Spring 1918, Allied and German help arrived in earnest, the Don Cossacks revolted, and the Civil War proper began.

Comparisons with Spain

Beevor compares the Whites to the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War because, like the Republicans, they suffered from internal divisions. [7] But to my mind the White Russians far more closely resemble the camp of Franco. Hitler and Mussolini drew popular support from the middle layers of society. Franco was called a fascist and called himself one, but unlike Hitler or Mussolini he was part of the establishment. The actual fascists (Falange and JONS) were only one component of his coalition. With their alliance of clerical, aristocratic, bourgeois and military elements, the Francoists and the White Russians were remarkably similar.

There are differemces. The Whites presented a ‘democratic’ face to preserve the Allies from embarrassment while Franco, having plentiful aid from fascist countries, had no need to hide. Another contrast is that Francoist terror was systematic, top-down and clearly aimed at extermination [8]. Maybe the Whites killed roughly as many people as Franco did (nobody knows), but in terror as in most things, they were not systematic.

In short, the Whites can be called proto-fascist, but only in the broad sense that the term ‘fascist’ would apply to Franco.

The key difference between the Spanish and the Russian civil wars lies in the position occupied by the professional middle classes (sometimes called the petty bourgeoisie or, in Russian terms, the ‘Intelligentsia’). In Spain, the workers and poor farmers generously permitted the professional middle classes to lead them (to defeat) in an alliance known as the Popular Front. In Russia, assertive workers’ representatives, in the form of the Bolsheviks, did not permit the intelligentsia to assume leadership of the Revolution. So the intelligentsia fled to the White camp where they strutted and fretted their hour upon the stage before they were overthrown by forces to their right.

If the Bolsheviks had gone into coalition with the Mensheviks and Right SRs on the terms demanded of them in coalition talks in November 1917, I think it’s likely the Russian ‘Pan-Socialist Coalition’ would have met the same fate as the Spanish Popular Front.

Intervention

The ugly things the early Soviet regime did (of which, more in Part 2) could only have happened in the context created by the military onslaught of the old ruling classes backed by the whole ‘civilised’ world. Nye Bevan, architect of Britain’s National Health Service, believed that the later development of Stalinism could be traced back in large part to the brutality inflicted on the early Soviet Union by the Allies:

I remember so well what happened when the Russian revolution occurred. I remember the miners, when they heard that the Czarist tyranny had been overthrown, rushing to meet each other in the streets with tears streaming down their cheeks, shaking hands and saying: ‘At last it has happened.’ Let us remember in 1951 that the revolution of 1917 came to the working class of Great Britain, not as social disaster, but as one of the most emancipating events in the history of mankind. Let us also remember that the Soviet revolution would not have been so distorted, would not have ended in a tyranny, would not have resulted in a dictatorship, would not now be threatening the peace of mankind, had it not been for the behaviour of Churchill, and the Tories at that time. [9]

To this day, writers in the English-speaking world write of their countries’ invasion of Soviet Russia as a silly farce. They dismiss the idea that intervention was a serious matter at all. The whole thing, we are assured, was blown out of proportion by Soviet historians.

But all I hear is, ‘Why are the Russians so angry about it? We only invaded them a little bit.’

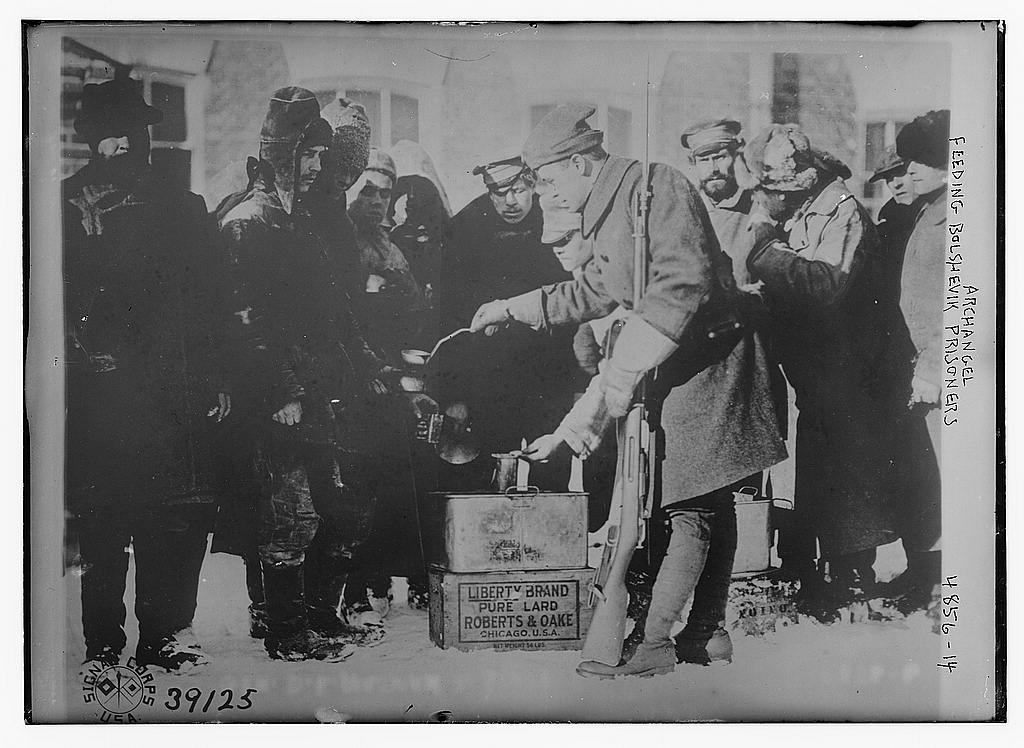

Allied intervention was desperately sought and deeply appreciated by the Whites. When a White leader recieved the blessing of world empires and regional powers, it was a great boost to his prestige. But that was only a part of the package. It also included supplies – food, bedding, clothes, fuel – and vast quantities of weapons, enough to arm and equip every White soldier several times over (see the graphic below). The White leader had stable, well-trained Allied forces garrisoning his rear and guarding his railways. He had advisers at his side. He had financial credits. He had, at his back, the most powerful navies in the world waiting to evacuate him, his soldiers and their wives and children, just in case he still somehow managed to lose. The Whites had all that and the Reds had none of it.

The interventionists also outright invaded. The Japanese government had 70,000 troops in Siberia at one point, engaged in full-scale war with Soviet partisans. Germany occupied a vast territory with a vast army in 1918. The French and Greeks sent in a force of 65,000 in 1919. The Czechoslovak Legion numbered around 50,000. All that is to say nothing of Poland in 1920. Other interventionists sent in troops by the thousand and not by multiple tens of thousands. However, the prospect of a full-scale Allied invasion no doubt helped encourage many young lads to enlist in the Whites who might otherwise have stayed home. The French invasion of Ukraine in 1919 was inhibited not by the qualms of the French government but by the mutiny of the French soldiers and sailors.

In North Russia, the interventionists had around 15,000 soldiers by summer 1918 – British, US, French, Italian, Serbs, Czechs and Poles. The local Whites could only muster 5 infantry companies, one cavalry squadron and one battery. [10] On this front it was not a question of intervention in war – the Allies were the war. Here more than elsewhere they fought directly with Soviet forces.

More galling still is the accusation that the Soviet regime was responsible for all deaths by famine and disease in these terrible years. [11] The country was hungry for years before the Revolution, ever since the economic demands of the First World War upset the delicate food supply system. The Tsarist army engaged in forced requisitioning. The German government looted Ukraine of foodstuffs. The Allies blockaded Russia, a repeat of a policy of artificial famine that was employed against the German people in the First World War. All the interventionists knew that in supporting the Whites they were disrupting exchange and production in an already half-starving country. When famine struck in 1921-2, no foreign government contributed to famine relief. The non-government American Relief Administration saved countless lives before future president Hoover withdrew it for political reasons. [12]

Trudell writes that ‘Foreign intervention also played a devastating role in the containment of the Revolution within Russia’s borders.’ Quoting Chamberlin, she adds that if Allied aid had ceased in November 1918, ‘the Russian civil war would almost certainly have ended much more quickly in a decisive victory of the Soviets. There a triumphant revolutionary Russia would have faced a Europe that was fairly quivering with social unrest and upheaval.’

The British leaders knew that the Soviet regime was popular and were well aware of the bigotry and corruption of the White forces. According to a July 1919 British government memo, ‘No terrorism, not even long suffering acquiescence, but something approaching enthusiasm’ could explain how the Soviet regime had held onto power. ‘We must admit then that the present Russian government is accepted by the bulk of the Russian people.’ [13] But the British government did not cease supporting the Whites until almost a year later.

Readers may find the vacillations of the Allies confusing. The explanation is this: there was a logic to supporting the Whites even if their defeat was certain; the war would weaken and contain the Soviet Union. In order to contain revolution, the Allied leaders prolonged this war by at least two years, condemning countless innocent people to death by starvation and epidemics.

‘We workers blamed our hunger on the counterrevolution, not on our regime,’ wrote Eduard Dune. [14] They were right.

My impression of the role of the interventionists is very far from the picture of well-intentioned bumbling that is often presented to us. I’m reminded of the words F Scott Fitzgerald would write a few years later in The Great Gatsby about a bourgeois couple in the United States: ‘They were careless people […] —they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made….’

Ironies

The vast numbers of poor and working-class people who supported the Soviet regime were denounced at the time as ignorant, savage, criminal and even animal. The people who were responsible for the First World War called them violent and irrational. But these supposed ‘illiterates’ were fighting for progressive and modern causes: against domination by kings, priests and landlords, against racism and empire, for women’s liberation, for workers’ rights, for the extension of democracy into the workplace. They legalised abortion and same-sex relationships many decades ahead of other countries.

Another irony: they entered upon this struggle with the perspective that they only had to hold out until other revolutions in more developed countries would come to their aid. But as things turned out, they had to fight not only their own ruling class, but the whole world. The early years of the new regime were spent in battle: fighting to stave off the bloody fate that had met the Paris Commune and the Finnish Soviet; fighting against hunger and disease; ultimately fighting, due to these great pressures, against the threat of social collapse and political and moral degeneration.

Soviet victory in the Civil War was remarkable. ‘It was amazing, given the massive forces – both internal, and those of Allied intervention ranged against them – that the Soviets managed to ride out such compressed storms of horror and emerge victorious.’ [15]

The regime that emerged, limping and traumatized, from the horror of the war fell far short of what the masses had set out to fight for in 1917. But this, at least, was neither ironic nor remarkable. The Soviet leaders had predicted that far worse would come to pass if the revolution did not spread westward. It was also the entirely predictable result of the devastation caused by the war. Speak with caution about the results of this ‘socialist experiment’ – the lab was set on fire by arsonists.

Next week we will look further into these issues. Stay tuned for Part Two of this conclusion.

Revolution Under Siege Archive

[1] Jackson, At War With the Bolsheviks, p 235

[2] See the introduction to Engelstein, Russia in Flames

[3] Trudell, Megan, The Russian Civil War: A Marxist Analysis

[4] Smele 117

[5] Smith, S. A.. Russia in Revolution, p. 171

[6] Mawdsley, 389

[7] Beevor, Russia, ‘Conclusion: The Devil’s Apprentice’

[8] See Paul Preston, The Spanish Holocaust

[9] Quoted in Nye Davies, ‘At Last it has happened’: Bevan the Russian Revolution and the Soviet Union.’ Published on 31 Oct 2017 by Cardiff University: https://blogs.cardiff.ac.uk/thinking-wales

[10] Khvostov, White Armies, p 8

[11] Again, see Beevor, Russia, ‘Conclusion: The Devil’s Apprentice’ – but really this accusation, implicit and explicit, is everywhere.

[12] Trudell

[13] Ibid

[14] Dune, p 123

[15] Bainton, Roy. A brief history of 917, Russia’s year of Revolution. Robinson 2005, p 206

2 thoughts on “Revolution Under Siege: Conclusion (Part 1 of 2)”