How was life in the Stone Age? Was it all people shooting arrows at one another and falling into glaciers, or was it one big hippy commune? In this chapter Graeber and Wengrow leave behind the Enlightenment and start a chronological study of the earliest human societies, focusing on society in the Upper Paleolithic period. That’s the final part of the early Stone Age.

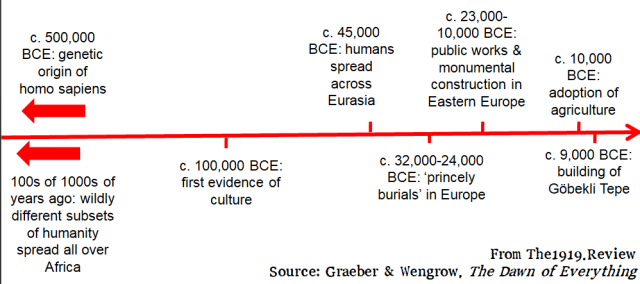

The first thing I learned here was pretty surprising: that humans lived spread out all over Africa for hundreds of thousands of years, with strong regional variations that meant they would have resembled giants, elves or hobbits to one another.

Then homo sapiens formed from a composite of all these very different sub-species, moved north into Eurasia, met the Denisovans and Neanderthals, and in time absorbed them.

The authors then perform the by-now familiar shuffle: thesis, antithesis, forget-about-either-thesis. Hobbes was wrong, Rousseau was wrong, here’s a better explanation.

Princely Burials

What about the Upper Paleolithic ‘princely burials’ in Europe? Are these richly-endowed graves (countless person-hours of labour would have gone into them) not evidence of a rigid social hierarchy like what Hobbes said?

Reading about ‘princely burials’ myself in other contexts, I’ve always been annoyed at the assumption that they necessarily indicate social hierarchy, aristocracy, etc. An individual might be honored in death for all kinds of reasons – for heroism in battle or skill in crafts, for being an inventor, for saving lives, for poetry, for metallurgy, for mystical visions. They might be honored for being great leaders, but this doesn’t mean they were aristocratic ones.

Graeber and Wengrow make an argument along similar lines to my guesses – that these were eccentric and visionary outsiders-turned-leaders, who were buried in riches (at a time when no-one was buried in death, with or without riches) as much to contain their potentially dangerous magic as to honour them. They construct a whole argument which takes in anthropology and archaeology, and which I found convincing.

So far they are at least living up to one promise: their version of history is interesting and rich. Our heads are full of capitalist and feudal assumptions, so we have to remember that just as objects which travel a long distance do not always indicate mere ‘trade’, elaborate burials do not always indicate ‘ruling class.’ The past is so much broader than the scopes of capitalism and feudalism through which we view it.

Monuments

We see the same pattern with the other type of artefact from the Stone Age which, like ‘princely burials’, are often taken up as proof of hierarchies and kings: grand, monumental buildings.

I’ve come across the fantasies of Graham Hancock and Ancient Apocalypse, in which Göbekli Tepe is evidence not just of kings but of an entire ancient empire which was more advanced than us and which left cryptic celestial warnings, and which colonized the world ‘teaching’ people how to do agriculture and masonry. A lot of the narrative hinges on the idea that Stone Age hunter-gatherers could not have built great stone monuments.

Even though they are so florid and fantastical, such arguments have always struck me as paradoxically boring. There is a more-than-open attitude to the possibility of Atlantis, aliens and giants, but dull pedantry when it comes to ancient societies. In unimaginably long stretches of time, tens of millennia, Graham Hancock cannot see any possibility that hunter-gatherers could have established a society which was, even temporarily, capable of building something like Göbekli Tepe.

Like with the burials, here Graeber and Wengrow give us a bit of archaeology (Stonehenge, Göbekli Tepe, Russian mammoth houses) and a bit of anthropology (such as the Inuits, the Nambikwara in Brazil and the Plains Indians in the United States) and paint a picture that is colourful and informative. I mean colourful not like atlanteans came along one day to teach us about seeds and the principle of the lever, but more like nomads and hunter-gatherers vary their social systems from season to season, sometimes gathering for great coordinated collective labour, sometimes dispersing to hunt and gather.

It’s satisfying to get a clearer idea of how these monuments were built. But the best part is the idea that these societies changed their whole social system regularly to meet their needs. In one part of the year, the modern Nambikwara roamed in small bands, all these bands being under the strict control of one chief. For the other part, they gathered in hilltop villages, became democratic and communist, and had chiefs who functioned more like a social welfare department than a monarchy. But across all the other examples, no single pattern prevails: among one people, there is a settled season of strict hierarchy and a roaming season of relative informality. Among another, police functions are strictly seasonal and rotate between clans on an annual basis.

The anthropological stuff gives an insight into how Stone Age peoples might have lived: gathering after a great hunt with a superabundance of food and other goods, feasting, processing materials, building great structures, then dispersing again when the seasons turn.

What’s the upshot of all this?

Prehistoric society was not a realm of innocence or animal instinct – our ancestors were politically sophisticated.

Prehistoric society was not all one thing. A grading of one political system alongside each economic mode (for example, claiming that hunter-gatherers live in ‘bands’, horticulturalists under ‘chiefdoms’) is too pedantic even as a general guideline.

And here I kind of get the ‘plague on both your houses’ approach to Rousseau and Hobbes, because it’s ultimately from Rousseau that we get the idea that people pre-state and pre-class were simple and innocent.

However, this wouldn’t have been my understanding, and I’m broadly in the Rousseau ideological legacy. So they’re only throwing out bathwater here. Fine by me.

They haven’t succeeded in turning me off the idea of an economic basis corresponding to a political regime. Hunter-gatherers never seem to get around to parliamentary democracy, fascism, Stalinism, the Paris Commune or the Petrograd Soviet – not because they were/are too innocent to think of them, but because these systems do not correspond to their needs or means. The above are political systems proper to our age. There is a wide range of them, and which one you end up with depends on the last analysis on the outcome of a political struggle. But a certain type of economy, one where things like factories and railways are central, is a necessary prerequisite.

Though it seems political systems are more broad and fluid the further back you go. Even what we file under ‘feudalism’ is by definition immensely varied and full of local peculiarities. And when I looked at Gaelic Ireland, I realised that under its legal constitution many different de facto regimes could exist, depending on hard factors like population and resources and soft factors like politics and culture.

But even that phrase ‘the further back you go’ is weighted with an assumption, isn’t it? An assumption about progress, development, advance. That economies actually do develop through stages, and do not slip backwards as easily as political systems do; it’s never actually happened that a country has been ‘bombed back to the Stone Age.’ I admit thermonuclear weapons do raise the possibility.

I guess Graeber and Wengrow wouldn’t agree, but it is possible to speak of progress and development and economic stages without being racist or reductive.

Our industrialized world has global warming, endemic and stark inequality, addiction, shanty towns, systematic cruelty to migrants, homelessness for the sole purpose of enriching landlords, debt bondage as a precondition for housing, widespread precarity,long hours and low pay, universal exploitation, and hysterical bigotry against anyone who’s different. It also has vaccines, washing machines, incubators, clean running water, and a super-abundant supply of manufactured goods. I think that second collection of things are more than mere creature comforts or mod cons – yes, even the manufactured goods that clutter my house and ‘do not spark joy’ – and what’s more I don’t see that they are predicated on the first set of things, the bad things, or dependent on them in any way.

The Marxist criterion at work here, as I’ve mentioned before, is the productivity of labour. In relation to that, we can speak of our society as being advanced or developed in relation to a society that lacks these things.

But the bad things listed above, and their absence in prehistoric societies, are a reminder that our society is still at an absolutely pitiful and contemptible level of development. The idle person who thinks it’s OK for him to be thousands of times wealthier than a nurse or cleaner, just because a piece of paper says that he owns this or that, is a victim of the greatest superstition that has ever held sway over the human mind. The 16th-century German had more reason when he bought indulgences off Johann Tetzel, and the Aztec priest had more practical common sense when he ripped the hearts out of war-captives to keep the sun in the sky.

The most valuable insight from this chapter – and it is a refutation of Rousseau whatever way you slice it – is that hierarchy is not a necessary overhead of (a) social complexity or (b) large population or (c) collective projects or (d) coordination over long distances. Sure, hierarchy is one way to do it, and indeed one way that it appears to have been done even in some pre-class societies. But this chapter tells a story of political sophistication and huge monuments, apparently without hereditary rulers or coercion.

I grew up with Gary Larson images of people living in caves and even coexisting with dinosaurs (Yabba dabba doo!). But even as a more well-read adult I still would have thought that before agriculture, people lived in small roaming groups of a few dozen people. This chapter has challenged this idea, but in a way that is actually very encouraging. These pre-agriculture, pre-state, pre-class societies could be large, complex and at least seasonally settled. Probably they had a wide variety of social structures, including hierarchies and castes, but these were not the rule.

One thought on “Before the Fall (3): Notes on The Dawn of Everything”