David Cornwell began writing fiction (under the pen name John le Carré) while working as a British intelligence officer in Central Europe in the middle of the century. Talking to Channel 4 in later life, he said that during this espionage work he was never himself in any danger. The interviewer asked a good follow-up question: whether he had ever placed anyone else in danger. Le Carré replied, with a stony expression, that he would rather not say. The camera lingered on his face and we could read there what we read in his books: the troubled conscience of a spook.

I have surprised myself by reading an unlucky number of the novels in which this man wrestled with his conscience. That is, half of the 26 novels he published in about 60 years. Some of these I’ve read, others I’ve had read to me by the excellent Michael Jayston thanks to Borrowbox and public libraries. If those thirteen novels skew toward his best works, and I think they do, then I’m in a pretty good position to give some recommendations. Over this and the next few posts I’m going to give my short review of each one.

I’ve tagged this post ‘What are the best John le Carré books.’ But my regular readers may have noticed that I don’t go in for scoring books out of 100, or even ten or five, and I’m not keen on rating them like athletes. It would take me twenty seconds to tell you the five le Carré novels that, right this minute, I imperfectly remember liking best, according to my tastes and opinions at the time I read them, for what that’s worth. But these are all very good books. It would be more purposeful to write a little about each one and what I thought about it. At the end of each post I’ll offer some gestures toward rankings and recommendations. If you want to know which le Carré book to read, and if you’re going to take my word for it, take a few thousand words while you’re at it.

Call for the Dead (1961)

Le Carré’s first novel was a murder mystery and not really an espionage novel. But Call for the Dead introduces his most well-known character, George Smiley, a quiet and retiring senior spook (literally – like Iron Man, he retires at the end of every novel only to show up again in the next). We begin by learning that his beautiful wife has run off with a race-car driver, and by seeing his stoicism in the face of this betrayal. Smiley’s humility conceals his sharp mind and dogged will. As the novel opens, he has been running security checks on a civil servant named Fennon, only for that Fennon to turn up dead, apparently by suicide. Smiley is not fooled – Smiley alone is not fooled – and he starts unravelling a case that involves East German spies. It is a short, sharp story that’s well-paced and populated by compelling characters.

Many features that will become familiar in le Carré’s world here resolve themselves out of the mid-century murk for the first time.

Communism appears as an illiberal, violent and underhanded force. But it’s not some cosmic evil from outside space and time. Of our three characters who are (or used to be) communist, all have good motives. The civil servant Fennon took part in hunger marches with Welsh miners; his wife Elsa is a holocaust survivor who is enraged to see former Nazis creep back into power in West Germany; Frey is a dedicated anti-fascist who used to be an agent of Smiley’s during the war. Smiley doesn’t hate his adversaries. Rather, he feels a pained and partial self-recognition when they reveal themselves. Smiley sees more of himself in them than he sees in his own pompous and parochial superiors.

How is it different from later le Carré? There is no real critique of Britain’s intelligence services, no forays beyond the Iron Curtain. All in all, we are in cosier territory here.

When I read this: c 2023

Locations: London

Why read it? John le Carré’s first novel; George Smiley’s first appearance; an accomplished thriller.

Memorable moments: When Smiley arrives home to find an East German spy opening the door for him, only quick thinking and a cool head save his life.

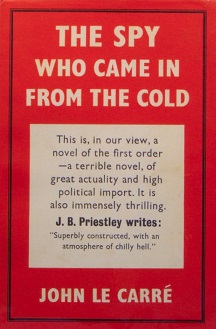

The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1963)

The Spy Who Came in from the Cold was written when the Berlin Wall had just been built, and it captured the zeitgeist powerfully, going on to wild commercial success.

Alec Leamas is a burned-out, hard-drinking spy whose agents have all been exterminated by East German intelligence. He returns to London where Control (leader of the intelligence agency known as ‘The Circus’) enlists Leamas for one last solo mission. While Call for the Dead was a traditional murder mystery, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold has a brow-furrowing plot revolving around spy agencies bluffing, double-bluffing and triple-bluffing each other. As the novel goes on it gets more claustrophobic and paranoid.

It’s not a spoiler to say that Leamas has been lied to by Control (and by Smiley, who puts in a few appearances). The villain Mundt returns from Call for the Dead, and Fiedler, a principled and well-intentioned Jewish communist working for the Stasi, channels familiar energies (perhaps an echo of Frey, though to a more tragic end here). Towards the end Control’s real agenda is revealed as devastating and ruthless. If you ever catch yourself feeling too warm and fuzzy about George Smiley, remember what he did to Alec Leamas and Liz Gold.

Gold is a young woman Alec Leamas meets when he’s busy building his legend prior to his final mission (A ‘legend’ in this context is a kind of espionage method acting – the cover story which a spy not only concocts but lives and documents in order to fool the other side.) Soon Leamas learns something surprising about his girlfriend.

She tentatively begins to explain ‘I believe in history…’ and he bursts out laughing. ‘You’re not a bloody communist, are you?’ She has no idea her boyfriend is a wounded cold warrior, so she’s a bit confused at his amusement, but she’s relieved that her political affiliation doesn’t scare him off.

That’s a good moment, with irony flying in all directions, but I think le Carré’s depiction of Liz is patronising overall, and it’s a weakness of the novel. I get that she’s supposed to be the innocent in all this, but she’s way too innocent. She actually dislikes everything about being in the Communist Party apart from the peace marches. Her party comrade is simultaneously a gay man (portrayed without sympathy), and a lech toward her. She tolerates all this and more for reasons that are not clear. A more streetwise Liz would have been just as sympathetic but more believable – someone who, like Leamas, has made ethical trade-offs to pursue what she believes is right.

When I read this: c 2011

Locations: East Germany, London

Why read it? The novel that made John Le Carré’s name and launched his career; his first spy novel proper, introducing his dark and morally dubious portrayal of the world of espionage

Memorable moments: The story begins and ends with desperate people making a break for it at the Berlin Wall – whose construction was recent news at the time this book was published

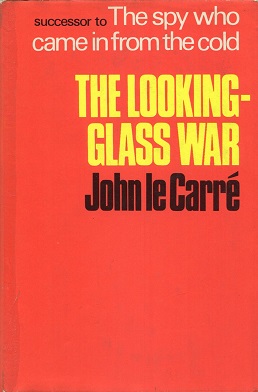

The Looking Glass War (1965)

The Looking Glass War is a brutally unglamorous story. It revolves around The Department, a distinct intelligence organisation overshadowed by George Smiley’s ‘Circus.’ The Department has been reduced to a small staff without much funding, with its Director Leclerc wallowing in a perverse nostalgia for the days of World War Two, when he used to regularly send young men to their deaths. When an East German defector brings hints of a missile build-up, Leclerc embarks on an escalating series of risky operations to verify the data. Our main characters fear an imminent re-run of the Cuban Missile Crisis, but beneath their fear they really want to believe it’s true. Because, what a coup for The Department! They feel they deserve this. For most of the book we don’t know if we’re in the midst of a cock-up or a conspiracy.

At the climax, we follow an agent on a quixotic mission beyond the Iron Curtain. But mostly the conflict is office politics, the cause is nostalgia and bureaucratic prestige, and the subterfuge is inter-agency rather than international. For example, the Department has to borrow radios from the Circus, without letting them know anything about the intel they have or the operation they are planning. If the Circus get wind of it, they will take over. Le Carré is good at making office politics compelling, at describing one self-important bureaucrat witheringly through the eyes of another equally self-important bureaucrat. He appears to loathe the upper tiers of British society, but he speaks effortlessly in their voice.

The most memorable character besides Lelclerc does not fit into the familiar British-officer-class mould at all. This is Fred Leiser, a Polish immigrant who played a heroic role behind enemy lines for The Department during World War Two. Leiser has no stake in the intelligence world anymore; he has settled into civilian life. But the Department convince him to come back and risk his life on a mission into East Germany. I was pretty horrified at how this poor guy is groomed and flattered and tricked. At the same time Leiser is a strong-willed, rather arrogant character who actively chooses to do this, and for all the wrong reasons. Le Carré had evidently learned how to portray a guileless innocent.

And if we’re going to talk about themes that will be big later making their first appearance here, consider The Department as a metaphor for post-imperial Britain. In later novels we see The Circus itself in the same position as The Department, with the CIA as the bigger counterpart from whom it is trying to secure resources, but also to keep its petty secrets and barren intrigues.

When I read this: c 2023

Locations: Finland, West Germany, East Germany, London

Why read it? A more tragicomic take on the dark underworld of intelligence; all the troubling morality of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold but with murkier stakes.

Memorable moments: We are subjected to a scene of haunting dismalness when Avery visits the flat of his colleague who has died mysteriously while on a mission; later, we have the humorous tension between Fred Leiser and the sergeant who is training him.

Honourable mention here for A Small Town in Germany (1968), which I tackled in 2011 or so but didn’t get far into. It concerns a fictional and (then) near-future student movement in Germany which espouses an inchoate mishmash of left and right politics. I think I was put off by the author’s dismissal of the student radicals. I remain curious and might tackle it again.

Summing up… (and my favourite of these three novels)

The basic pitch of early le Carré was that he was selling a more unvarnished truth about intelligence – Forget James Bond, he seemed to say, this is the real deal; none of that moral complacency, none of those innocent assumptions about right and wrong. In its place the vision offered by early le Carré is that the West is benevolent and the East is malevolent, but that in the struggle the West has regrettably lost sight of its principles, and in terms of methods the two sides are equally devious and cruel.

Except not really, because in le Carré novels we see the Stalinists doing much worse things than we see the imperialists doing. Even leaving that aside, though, isn’t that vision complacent in its own way? The idea of Britain and the United States as basically benevolent and good forces in the world, in contrast to the wicked Soviets, is not really compatible with my own understanding of the broader history. I know what the Soviets did in Hungary. But men of Leamas, Smiley and Guillam’s vintage ran gulag archipelagos in Malaysia and Kenya. The Soviets imposed dictatorships in Eastern Europe, and the capitalist countries imposed their own on their side of the Iron Curtain, for example in Greece. The Stalinist states were certainly cruder in their repressive methods than, say, the British state when operating on British soil upon white British subjects. But the Soviet bloc was basically conservative and defensive, not expansionist or aggressive. So the reality is murkier still than we see in early le Carré.

The paranoid multi-layered duel of deception in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold is very powerful. But of these three novels, I most admire The Looking Glass War. Its tragicomedy and its basic theme of utter delusion ring truer to me given the above points.

Le Carré’s novels of the 1960s were tight and focused. They were thrillers in cheap covers that I imagine you could carry in your jacket and read on the London Underground. In the 1970s, which I’ll look at next week, Smiley’s chilly and foggy world expands to an epic scale. These early novels have plenty of tension, humanity and power, but they are apprentice pieces by comparison with what is to come.

One thought on “Dubious Crusades: John le Carré in the 1960s”