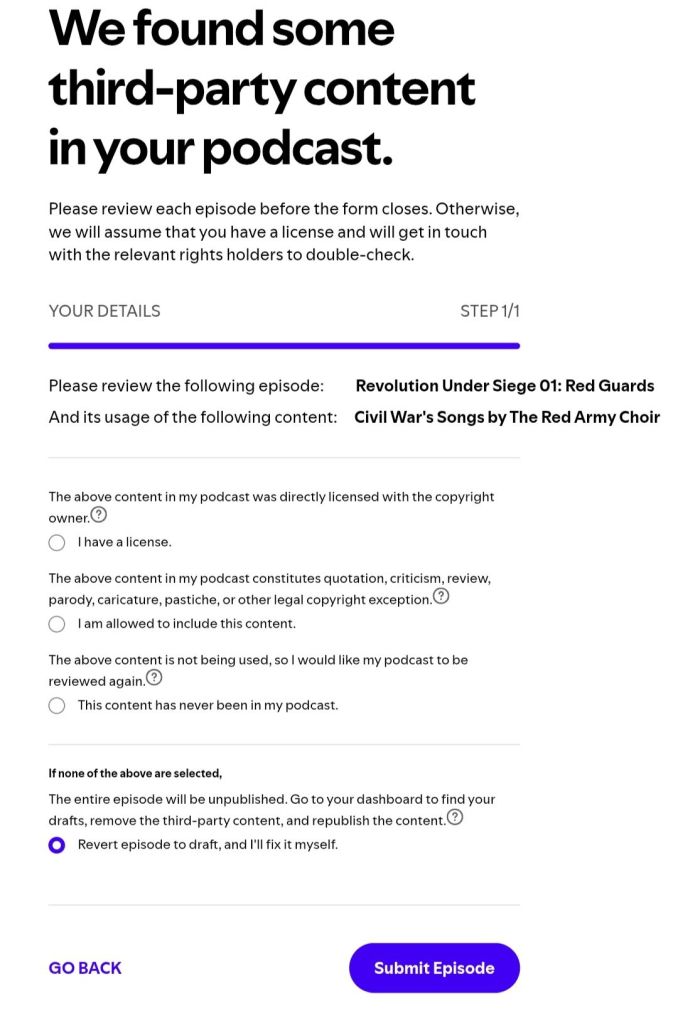

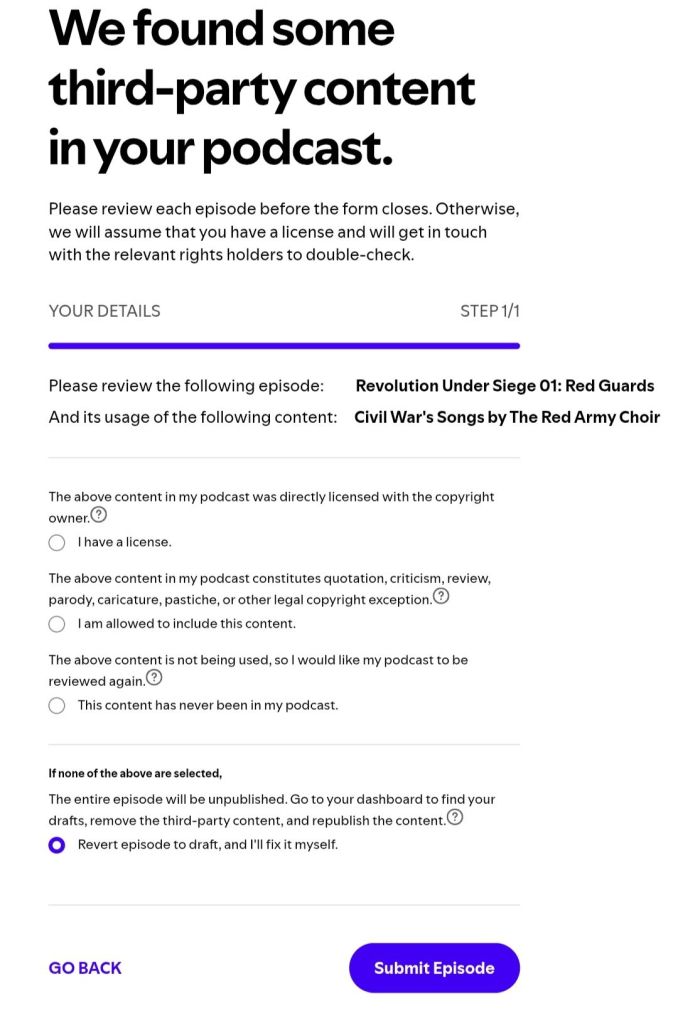

Spotify are being litigious on behalf of… [checks notes] …the Red Army Choir?!

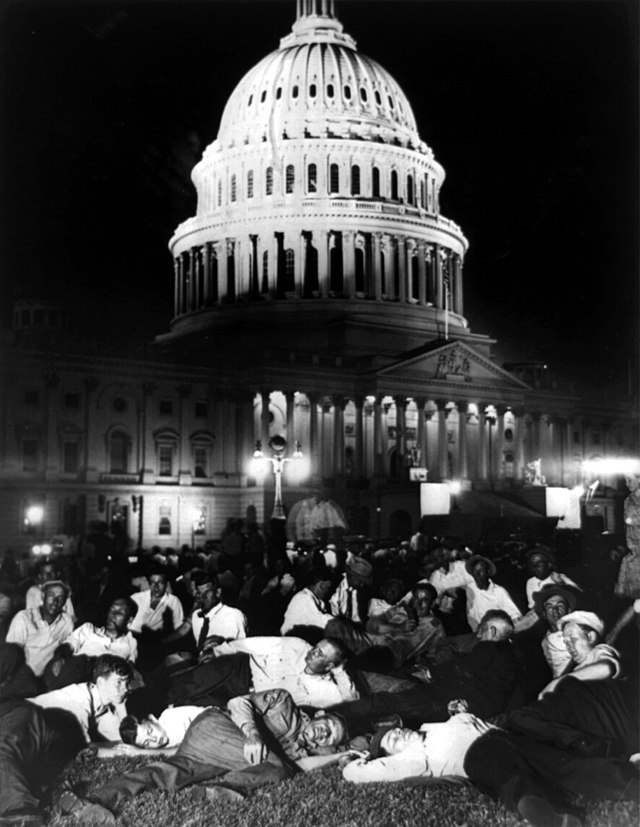

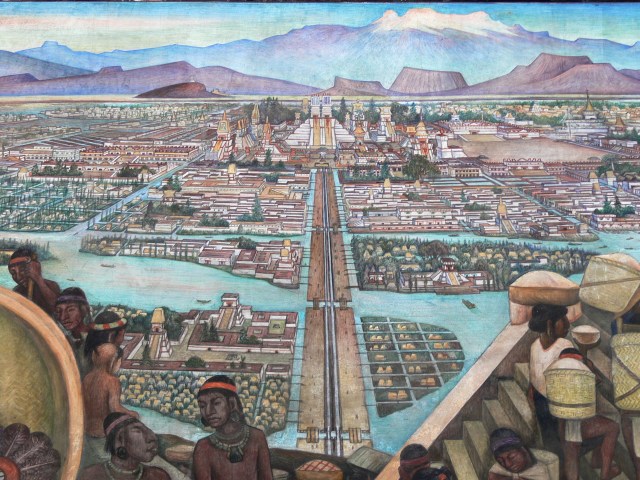

The Lacuna is a 2009 novel by Barbara Kingsolver about a young Mexican-American man, Harrison Shepherd, growing up in the early 20th Century. During his fictional life, spent back and forth between Mexico and the USA, he encounters real events and people, such as when he sees the Bonus Marchers beaten and gassed off the streets of Washington DC in 1932, makes friends with Diego Rivera and Frieda Kahlo in Mexico City, and back in the US finds himself in the firing line of the McCarthy Red Scare.

It’s a great novel that deserves all the praise and prizes that it got. In this brief post I want to zoom in on one interesting feature: its depiction of the Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky. Trotsky, who lived in exile in Mexico city from 1937 until his murder in 1940, occupies a prominent place in the story. His depiction is something I’m going to praise but also criticize.

Kingsolver, who cut her teeth writing about miners’ strikes, treats the workers’ leader Trotsky with great sympathy. He appears to Harrison as a short, strong man with the dignified appearance of an older peasant, who is passionate about animals, nature and literature as well as politics. He employs Harrison as a secretary and, when he stumbles upon the young man moonlighting as a writer, gives him precious encouragement. An exile from Stalin’s Soviet Union, Trotsky is more melancholy than angry. Harrison is a witness to Trotsky’s murder and is haunted by the experience.

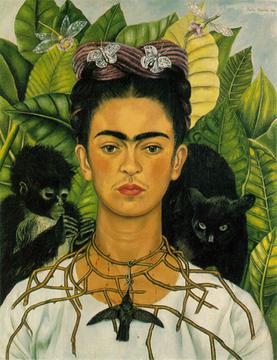

As an example of how she depicts Trotsky, in his affair with Frieda Kahlo (they did the dirt on their respective partners, Natalia Sedova and Diego Rivera), Kahlo comes out looking a lot worse than him. Harrison is Kahlo’s friend and confidante, and he judges her more harshly, probably because he knows her better; Trotsky is up on a pedestal and largely escapes judgement.

Kingsolver is interested in Trotsky but far more interested in Kahlo. We see Kahlo’s sharp edges, we are invited to judge her at times. But I guess this is because the author decided to make her a central character, to spend more time and energy on her. Trotsky gets comparatively less attention from the author, so we get a simpler picture of him. This is all fair enough. But this leads the novel into some avoidable missteps.

It’s not impossible that Trotsky would have employed Harrison as a secretary. Harrison is a veteran of the Bonus March, a supporter of ‘the dictatorship of the proletariat,’ (understood by him to mean democratic workers’ power) and a member of the leftist artsy milieu in Mexico City. Harrison is also young, and Trotsky was more politically tolerant toward younger comrades. But Harrison is, for all this, not very knowledgeable about or active in politics. I think Trotsky would have sooner entrusted such a key role to members of his own organisation, the Fourth International.

So it’s a very strange moment when Harrison asks how Stalin and not Trotsky ended up in charge of the Soviet Union. This should be something which Harrison already knows about and has developed opinions about, if he’s living and working in a trusted position in Trotsky’s household.

It’s a problematic moment in a bigger way, too. The real Trotsky wrote entire books about Stalin’s rise to power, so we know what he would have said. The explanation he gives in The Lacuna is wide of the mark. Trotsky, earnest and visibly pained by the memory, tells Harrison that he missed Lenin’s funeral because of a devious prank by Stalin. And so Stalin took centre stage at the funeral, and so, in this version of events, he became the sole possible successor to Lenin. I remember being told this by my school history teacher as an aside, as a touch of pop-history anecdote material, but I haven’t come across it anywhere since. Maybe it’s true as far as it goes, but it doesn’t answer the question.

And it’s definitely not the first answer Trotsky would give. In real life, Harrison would want to put the kettle on and pull up a comfortable chair before he asks Trotsky how Stalin ended up in power. Trotsky would not have spoken of personal intrigues; he was far more partial to grand socio-economic analysis and theoretical debates. If you open up his key book on the subject, The Revolution Betrayed, you can see this in the title of the first chapter; it’s not ‘Stalin: Devious Bastard’ but ‘The Principle Indices of Industrial Growth’.

In another strange scene, Trotsky laments the latest news from Russia: now Stalin is going after the ‘Yeoman farmers.’ But Stalin had started in on the ‘Yeoman farmers’ (kulaks) in earnest from 1929, and this conversation is happening around ten years later! In the early 1930s forced collectivisation and the ‘liquidation of the kulaks’ led to famine and terror on a huge scale. It was one of the most traumatic episodes in Soviet history and Trotsky wrote about it at the time. It wouldn’t have been news to him by the time he was in Mexico. In any case by then there were no kulaks left.

Trotsky in The Lacuna seems to regard these ‘Yeoman farmers’ as a key constituency whom nobody should mess with. This wasn’t the case. While Trotsky condemned Stalin’s onslaught on the peasantry and national minorities, he would still have used the derogatory term ‘kulaks’ rather than ‘Yeoman farmers.’ He saw the kulaks as a problem (though he advocated gradual and peaceful solutions) and earlier (in the mid-1920s) he condemned his opponents, including Stalin, for enacting policies that enriched and empowered this social layer.

In 1938 Trotsky’s son and close comrade Leon Sedov died in Paris, likely poisoned by Soviet agents during a routine surgery. In a powerful obituary, Trotsky expressed regret over his own often difficult personality:

I also displayed toward him the pedantic and exacting attitude which I had acquired in practical questions. Because of these traits, which are perhaps useful and even indispensable for work on a large scale but quite insufferable in personal relationships people closest to me often had a very hard time.

A more rounded novelistic portrayal of Trotsky would show us this ‘pedantic and exacting’ side, which was not a figment of Trotsky’s imagination – and perhaps his own occasional pang of regret over it. As his secretary, transcribing his extensive writings, Harrison would not only experience on occasion this ‘very hard time’ but would read practically every word Trotsky wrote. Someone as raw and open as Harrison would (rightly or wrongly is of no concern here) see some of Trotsky’s writings as ultra-principled or hair-splitting. This would especially be the case in the late 1930s; the extermination of all his allies and supporters back in the Soviet Union left Trotsky isolated, debating with the few survivors over questions which had no easy answers.

This depiction of Trotsky is incomparably more accurate and fair than the gothic, depraved supervillain we see in the 2017 Russian TV series. The 1972 movie The Assassination of Trotsky, starring Richard Burton in the title role, is a fair depiction and, I think, a good movie. We do see some steel in Trotsky’s character along with vulnerability. But I should mention that while I am far from its only defender, it was heavily and widely criticized as a film.

It’s believable and accurate that Harrison would encounter Trotsky and see a kind, curious, haunted man. But since he lived with him for a few years, he would see that like many great leaders and writers, Trotsky had his more negative personal traits. A more nuanced Trotsky, like the multi-faceted Kahlo we come to know in The Lacuna, would be all the more sympathetic for our having seen various sides of him.

Years ago I started but did not finish a Lee Child book, Killing Floor. The things I remembered most vividly from that book, more than a decade later, were the eggs and coffee. Why did I return, all these years later? A few reasons, but most of all because I wanted to see if the eggs and coffee still tasted the same.

You see, people compare Lee Child to Ian Fleming. Both phenomenally successful and violent page-turners, obviously. But the similarities run deeper. James Bond and Jack Reacher are not really about violence, or even sex. A large part of the appeal is travel, food and drink. James Bond flew to glamorous places and pickled his insides with fancy wining and dining. (I had to put down You Only Live Twice half-way through because the entire novel to that point was travelogue). Jack Reacher buses and trudges through un-glamorous places – close-to-home, bleak, dirty places – now and then dropping into a diner to order some eggs and a litre of coffee.

Now I’ve read three Jack Reacher novels in three months (that’s fast for me). Here they are, in the order that I read them:

What first piqued my interest was learning that the author is actually English. So it’s an English guy writing these familiar and jaded descriptions of the underbelly of the US heartland. That adds a layer of interest to every sentence. Why is he doing this, how is he getting away with it, and how is it so good?

Child doesn’t describe the taste or texture of the eggs or coffee in pornographic detail (It’s usually something like, “He had some eggs. They were good. The coffee was good too.”) But the food descriptions still get readers in the door. Can’t explain why, but I always feel rewarded when Reacher consumes his mundane fare.

Here follow more generalisations about Lee Child based on the three books I’ve read.

There are always cars. I’m car-blind – when an author tells me what kind of car it is (“a big coup deville” or a “large domestic model” or a “tan Buick”) it means nothing to me, and I don’t know what a given make or model is supposed to signify. But I know that James Bond cars are always that decade’s version of “fancy and expensive” while Reacher’s are more down-market. Reacher always borrows a few cars in his adventures and the reader gets to drive that particular car vicariously. The car stuff mostly goes over my head but I like how he drives across the States describing the natural and social scenery as he goes; transport is a medium through which to read the landscape. The circles described by irrigation booms are like marksmanship targets. A Georgia prison is described almost like the fortress of some evil sorcerer. In Midnight Line a truck driver briefly becomes a laconic therapist to Reacher.

Reacher always finds a way to have sex without it seeming shoehorned in. It might be central, it might be a sub-plot or it might be a coda, but it’s got to be in there. Reacher manages this while clearing a low bar that James Bond doesn’t: he’s not awful to women. He actually likes them, without a hint of contempt, and they like him.

This is good going for Reacher, when you consider that he regularly goes three or four days without changing his underpants (but we are assured that he uses “a whole bar of soap in the shower,” a defense which I find endearingly juvenile). If he carries a toothbrush, can he not carry some folded briefs and socks, maybe in his inside jacket pocket? But I guess Child is wiser not to get into all this.

I’m not a total novice to this kind of book. I’ve read Point of Impact (1993) by Stephen Hunter – the novel on which the movie Shooter is based. It’s a near-contemporary of early Lee Child and a cracking read. But the main character is an asshole. Not just to women, but also to men who talk too much (‘like a woman’).

Swagger and Reacher are both alienated from society (a character as lethal as them, while also being a boy scout, would be just unsettling). But Swagger is bitter, the distillation of a kind of post-Vietnam War resentment. Reacher starts off by telling us he’s angry that a president he didn’t vote for is cutting funding to the coast guard, an echo of his own redundancy – but he’s not bitter and he doesn’t retreat to his cabin in the mountains. He is alienated from the state and thinks the cherished myths of his society are bullshit. But he loves his country, and not in an abstract sense. He likes plenty of its people, its nature, the towns and cities and the vitality that flows on its highways. It’s a machine and he takes quiet delight in how well he understands its workings. Like what city a fugitive will be in after X number of days, what type of hotel he will stay in, and what false name he will adopt.

The stories always end with Reacher and his hastily-assembled team of allies assaulting the warehouse (or mansion or snowplough depot) where the bad guys are holed up. There will be not more than half-a-dozen action scenes before that, punctuating the story with thuds and cracks. My gruesome favourite was when he stalked five guys through a house in Killing Floor. But it has to be established that a guy is very bad before Reacher kills or maims him in a crunchy way; if the guy is only sort-of bad he only hurts him in a crunchy way.

One of the conventions of this genre relates to texture. Supposedly we are here for the murder mystery. But that’s not enough. In between the murdery and mysterious bits there are the moments where we are given access to insider information about interesting things like forgery, prescription drug abuse or guns. But even that’s not enough. In between all that, we want to follow the protagonist through a whole lot of relatable everyday life stuff like car rentals and jean sizes. The battles, puzzles and lore, in order to seem real to the reader, must be connected by a tissue made of the same stuff as our real and tangible world. The headbutts have to go crunch, and the narrator has to seem like an insider, but most importantly the eggs and coffee have to taste right.

“…throughout all the difficult days of the dissolution of Antiquity, we can trace the hard, selfish interest of a comparatively small group of families, their wealth and interest founded on land.”

-JM Wallace-Hadrill, The Barbarian West: The Early Middle Ages AD 400-1000. Harper Torchbooks, 1962

The book quoted above fell into my possession a little while ago. Knowing full-well that it was short, very broad, and decades out of date, I still read it with interest.

Men supposedly think about Rome every day. As for me, I’ve read some Robert Graves and played a lot of Total War (never as the Romans), but I’m not especially interested in togas and scutums and senators. But the stuff a little later, the great churn where the senators and castrums are turning into dukes and castles (but aren’t in any particular hurry) are more interesting to me. I like the times when years have three digits and there are a lot of things they haven’t invented yet, like chivalry, or Switzerland, or monks who had to keep it in their pants.

Today people put Rome and the Middle Ages up on a pedestal. But focus your eyes on where one is dissolving into the other, and it all looks more accidental and contingent, and you start learning things, often things you don’t know what to do with, facts you don’t know where in your brain to file.

I read indiscriminately about late antiquity and the early Middle Ages, and every so often I’m going to be posting about what I’ve learned. I might criticise what I wrote here in a future post when I read something else; or someone in the comments may have something to say. No worries. So here are some interesting things I found out from Mr Wallace-Hadrill and his book The Barbarian West.

I’ve seen the paintings. I’ve played the videogames. I grew up with a vague sense that there was a day when a horde of savages broke into Rome and burned a lot of nice buildings and murdered a lot of cultivated people, after which there was no more Western Roman Empire and Rome itself was finished as an imperial city.

Wallace-Hadrill says that the Goths took Rome in 410 CE, but did not actually sack it. They wanted food and land, and had no incentive to sack the city. It was back in Roman hands soon after. In 456 there was a serious sack of Rome – not by a nomadic horde, but by the powerful kingdom the Vandal invaders had established in North Africa. It was a sack, but it wasn’t the end of the Western Empire. That didn’t come until 476 and the overthrow of the last Western Emperor by one of his own Hunnic generals, Odoacer.

So the image of ‘barbarians’ sacking Rome doesn’t really convey how it all went down. Both Roman and invader by and large preserved Roman laws and institutions and even language – Latin itself had split into the dialects that would become French, Spanish and Italian before the fall of the Western Empire.

The later Magyar invaders, it is argued, did more damage in Western Europe than the Huns, while the twenty-year attempt by the Eastern Roman Empire to reconquer Italy brought about more destruction than the Huns, the Goths and the Lombards.

Why did Rome fall in the first place? On the internet and occasionally in print, I’ve seen people blame it on too much partying, too much sex, too many feasts, orgies, etc. Too much dole. Too much immigration. ‘Weak men create bad times’ etc, etc. If the commentator even notices the gap of centuries between supposed cause (vague ‘decadence’) and effect (fall of Rome), he is not remotely embarrassed by it.

Wallace-Hadrill sums up the 4th-century crisis of the Roman Empire in a few paragraphs. In that century, land was falling out of cultivation in all provinces, a sure warning of the collapse to come. Why?

The most striking point is that the people themselves were driven to revolt by intolerable conditions. We have slave revolts and disaffected farmers turning to “mass brigandage.” Later in the 5th century we have a Roman leader, Aetius, actually allying with the Huns to crush a massive popular uprising in Gaul (Aetius at other times allied with Goths against Huns and with Huns against Goths).

Farms had fallen behind because the whole system rested on enslavement, which held back new inventions and kept agriculture primitive. So from its backward agricultural economic base, the Empire couldn’t pay for its legions or for the palaces and luxuries of its ruling class. The vast external border was too expensive to defend properly. The expense was not just in money, because war casualties and conscription drained the labour force.

All in all, we get a picture of a system that has been pushed far past the limits of its own rules. Its drive to conquer others has led to overstretch and its reliance on enslaved people has led to stagnation. It’s not that the Roman ruling class ‘abandoned their virtues’ or that ‘good times created soft men.’ The problem was that the Roman landlords stayed true to their supposed ‘virtues,’ ie, to a system built on enslavement and conquest, even when it had ceased to deliver the goods on its own terms.

At first, Christianity didn’t take off in the Western Roman Empire. The aristocrats remained pagan; it was artisans and bourgeois in cities like Milan and Carthage who turned to Christianity. In the East, it was closely associated with the Emperor and with the state. What eventually spread in the West was a version of Christianity that took shape in the Roman provinces of North Africa, a more strict interpretation that defended spiritual power against secular power, ie church from state.

Early Christianity is a bit surprising. The first monastic community at Monte Cassino in the 6th Century was disciplined, but not ascetic. They all had wives and children. Rather than a place of quiet contemplation, it was a kind of bunker in a country torn by wars and plagues. As I said, this period is interesting to me because there are little surprises that I’m not sure what to do with.

In the seventh century we have Pope Gregory the Great. This pontifex maximus was last seen in the pages of The 1919 Review cruising the slave markets and cracking feeble puns about how good-looking the enslaved people were.

Here he appears in a different light. Presiding over a period of chaos, war and plagues, Gregory brings in a system of expensive and effective poor relief. “The soil is common to all men,” declared Pope Gregory. “When we give the necessities of life to the poor, we restore to them what was already theirs – we should think of it more as an act of justice than compassion.”

Couldn’t have put it better myself. I’m nearly tempted to let him off the hook for the ‘Not Angles, but Angels’ thing.

Charlemagne unified France and you could argue he founded Germany. He was a lawmaker and a patron of arts and religion. He converted the Saxons to Christianity at the point of a sword. A formidable character. But here’s a humanising and poignant detail about him from page 109. Wallace-Hadrill quotes a chronicler named Einhard as he goes on about how great Charlemagne was, how generous he was to the priests and to the arts, the churches he built, the treasures he bestowed. Einhard also says that Charlemagne kept tablets and parchment under his pillows so that when he got a free couple of minutes “he could practise tracing his letters. But he took up writing too late and the results were not very good.” He was a king from a line of kings – but in this age, he never got an opportunity to learn to write. He wanted to – but he was too old when he finally got the chance, and he only got to practise in odd spare moments. Even his flattering chronicler Einhard, looking at the messy lines and errors in Charlemagne’s uncertain script, has to purse his lips and shake his head sadly.

To finish, I want to note that books like this don’t come out anymore. And that’s for better and for worse. For better, because the author can be a callous prick sometimes. The later Merovingians died young of illnesses, so they were, he says, ‘physical degenerates.’ Sorry, what? But also for worse. This book is pocket-sized, accessible, unpretentious, erudite, focused. No hype, no bloat. An expert is informing the scholar or the layperson, and Harper are taking in $1.25 into the bargain.

So, Notes on the Medieval World isn’t really a series, more a theme I’ll be coming back to between long gaps, whenever I happen to finish a relevant book. Most likely the next one will be Passages from Antiquity to Feudalism by Perry Anderson. Stay tuned to see what videogame screenshots I manage to shoehorn in.

That word gets thrown around a lot. But I’m not racist – I’m just concerned. Specifically, about other races.

Why did you delete my comments from your page? All I did was try to dox the admins. All I did was send eight links, in a row, about people of colour doing crimes. All I did was drop fifteen ‘up yours’ emojis. All I did was blame asylum seekers for local unsolved or fictional crimes.

Well, well. It seems your page is not so open or welcoming after all.

Why did you turn off comments on that post? I only left eight comments. I had at least thirty more in me.

I had grand plans.

You don’t understand the beauty of a comment thread. It’s like a game of chess where you get to ignore your opponent’s moves and just keep on making your own. The winner is whoever sticks it out longer. I had gamed out every gambit and counter-thrust in our bout. Now it will never happen.

Why do you fold so easy? Why won’t you play with me?

…What?!

Now you’ve really crossed a line. You shared a news article about someone on my side doing something bad. How do you sleep at night, making baseless accusations? You want to get your facts straight. The nerve. I want video evidence. I’ll see you in court.

I got blocked from that page! So unfair!

All I did was send a message saying the admins were freaks and degenerate scum.

All I did was call refugees an invasion,

say that someone should burn down their homes,

and predict that they would be hunted down and beaten.

My expressions of glee were only implicit.

Please unblock me. Let me comment on your posts. All I did was ask if the admins were Jews.

And you couldn’t even answer that simple question!

Guess I struck a nerve.

Sad!

They’re afraid of the truth. They hate free speech. They refuse to let the people have their say. The facts don’t suit their agenda.

I’d even go so far as to say that they don’t appear to want to spend

all day,

every day,

reading my words.

Freaks. Sad!

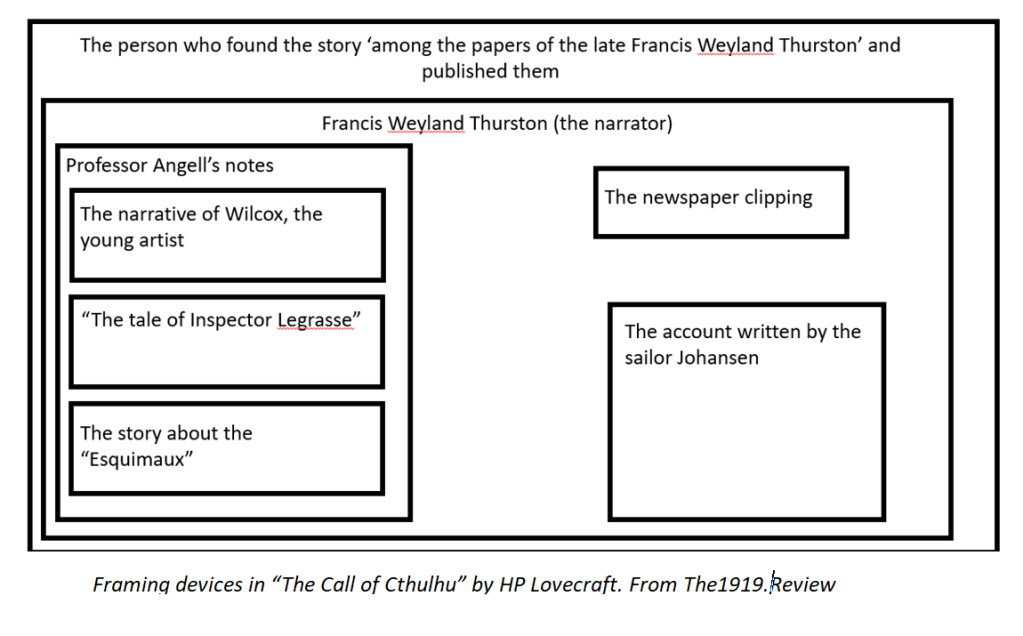

Re-reading HP Lovecaft’s work over the last year, I was struck by how he uses a complicated apparatus of nested narratives in his landmark short story “The Call of Cthulhu.”

Here they are:

This elaborate framing has several effects:

Lovecraft’s cosmic horror was rooted in North American racism but it resonates with people who don’t share these ideas because it transcends this base and reaches toward a more universal and – to me, at least – cathartic doomerism.

A thing I’ve come to realise from writing this blog is that it’s not so easy to write about things that are really good. I wrote brief things on Andor and the new Dune movies because brilliance speaks for itself and I don’t go in for gushing. It’s much easier to write about something you hate. Look how much I wrote on Antony Beevor’s Russia. It’s easier, and often it’s right and proper, but it’s negative and unhealthy.

The best thing is to talk about something of ambiguous quality. Something lots of people love, that you have big problems with, or something nobody gives a damn about but that you really like.

For example, Command & Conquer: Tiberian Sun.

In Part 1 I talked about the themes of Tiberian Sun (TS): its semi-accidental relevance in terms of ecology, and the dead-end politics of its very literal “end of history”. But on its face it is a story about a struggle between two magnetic characters, Anton Slavik (Frank Zagarino) and Michael McNeil (Michael Biehn).

Most people find that playing as the villain leaves a bad taste in the mouth. TS gets around this in clever ways. Anton Slavik is a high-ranking officer in the service of a ruthless totalitarian cult. But when we first see him, he is about to be executed as a traitor. So when we first see him, he’s a victim, he’s vulnerable, and we side with him instinctually.

Our identification with Slavik deepens as the story gets into gear. He escapes in a tense action scene, and soon we realise that his accuser, General Hassan, is the real traitor. It doesn’t matter a damn that Nod are evil; we root for real Nod over fake Nod. Our instinct for lesser evilism runs that deep. And when we see a genuine injustice being done on a complete prick, we extend the prick a partial forgiveness.

Slavik continues to command our respect, though not our affection, as his story unfolds. His overlord, the Nod prophet Kane (Joseph David Kucan), is a gloating and showboating kind of villain, video-calling his enemies just to mock them and quote Shakespeare at them before he blows things up. Slavik, by contrast, has a restrained and ultra-disciplined kind of fanaticism. He is ruthless, decisive, humourless.

His second-in-command is Oksana (Monika Schnarre). This is strictly a story for adolescents, and any intimate relationship between the two remains implicit. Oksana herself is a true believer, but allows her personal prejudice against “shiners” (mutants, AKA The Forgotten) to get her worked up. She serves as a foil to Slavik: in her light we can see more clearly that he does what Kane commands but without special rancour. This is not from lack of enthusiasm, but because such loss of control would be unbecoming. He only betrays emotion when we see in his eyes, to quote Liam O’Flaherty, “the cold gleam of the fanatic.”

Slavik’s GDI counterpart McNeil is more of a standard game character. He’s cocky but easy to like in spite of this. He has enough humility that later he learns a grudging respect for the mutants. An embrace is as far as him and the mutant commando Umagon get with each other on screen. Umagon and co even get McNeil to entertain doubts about his superior officer General Solomon (the late and celebrated James Earl Jones), who also harbours prejudices against ‘shiners.’

Why am I going on about Slavik and McNeil? Because TS is different from every other C&C game in this respect: it actually has protagonists.

How every other C&C title works is, in between each mission, some great actor like Michael Ironside or Grace Park turns to the camera and explains the plot with a straight face. Like: “Well done, commander. Roderick Spode and his Blackshorts are on the run. But we’ve just received some troubling news. The Anarcho-Aztecs have launched a full-scale invasion of Andorra. Thankfully, we have a new prototype anti-gravity device that should prove useful. Come on through to the lab, commander. Allow me to introduce you to Sir Isaac Newton…”

(Incidentally, my phone autocorrected Michael Biehn’s surname to ‘Biden.’ Jesus wept. Imagine him giving you a C&C mission briefing: “Let me tell you something, Mack… You did a good job with the uh, the Presinald Trunt, on the little battle fella…”)

Out of all of C&C, only in TS is “the commander” of each faction given a name and a face. Now that’s a risky choice because in trying to make a movie rather than a set of briefings, TS’s developers risk being ‘cringe.’ It is visibly low-budget and Bowfinger-esque in places, but all in all it turns out much better. The player is a third-person observer of a drama. There are human stakes to the missions. TS doesn’t have an Oscar-winning screenplay by any means (I think it accidentally stole the line ‘Get me McNeil’ from a parody movie featured in The Simpsons) but it engaged me in the story far better than any other game in the series. That is because the expensive professional actors were talking to each other, not to me. Sparks fly when Kane and Jones’ General Solomon confront one another on video calls.

No other C&C title, before or since, did this. So once again, TS stands out. Before I actually replayed it, I had the vague impression that TS was guilty of ‘taking itself too seriously.’ Not a bit of it.

The story is told through three media:

These three levels tie in together really well. The 2d isometric world, we understand, is only a representation of the real world. We’re at one remove. The action and dialogue clips supply a taste of what it ‘really’ all looks like, how it feels to be in this world, and our imagination does the rest.

Tiberium Wars and Kane’s Wrath have better graphics. They look great. But they lose this power of suggestion, the way these three levels of storytelling stimulate the imagination in TS. We don’t just play on the screen. We play in our imaginations, in the gap between the game’s now-primitive graphics and what this world would really look like.

We haven’t talked about the experience of actually playing TS. Well, if you’ve played one C&C title you have a pretty good idea what all the others are like. But here as elsewhere this game just feels subtly different.

Tiberium Wars and Red Alert 3 are fast-paced games. Each map feels like an arena, even the bigger ones. Turtling is usually punished; momentum and initiative are key. If you spend five minutes exploring, if you take an eye off your production queues, then before you know it some tank is going to be smashing in the garage door of your con yard.

Fast-paced is what they were going for, and it’s well-executed. But TS has something else, which I like better. It has empty space.

It has deserted plains and desolate canyons that lead nowhere. It has space, free uncertain space that might or might not have enemies in, and you won’t know until you send in a couple of buggies. There are no bright objective markers on the map; you’d better just figure out where those enemy SAM sites are the old-fashioned way, by sending out some guys who might get killed. This land was, emphatically, not made for you and me, which underlines the theme of the environment being indifferent to humanity. It makes the factions and the war they are fighting seem small in the grand scheme of things. This is in harmony with the game’s general vibe of being less gung-ho and more reflective than the average run of C&C.

(Going back to the cutscenes for a moment, the Nod ones start with a horribly realistic-looking shot of a dead Nod soldier, his helmet and the face under it both smashed. See what I mean? Less gung-ho, more reflective.)

And what is more, it slows the game right down. Other C&C games have an element of frenzied button-mashing and horrible meat-grinder combat where you produce wave after wave and send them out to be slaughtered. In TS, defence systems are solid and turtling is as good a strategy as any. While you hold the line, you explore, probe, experiment with different unit types, advance through trial and error, and by degrees refine your strategy, which may be very different from someone else’s. The final Nod mission, which involves setting up three massive missile launchers in enemy territory, is a fine example. There are several approaches to the main enemy base. I went in a roundabout way, battering through with rocket motorbikes, flattening a quarter of the base and bypassing the rest. I could have done it in a range of other ways, but I felt proud of the plan which I figured out and executed. Another good example would be the GDI mission where the enemy is launching poison gas missiles at you every five minutes. You have to choose wisely where to set up your base – it has to be somewhere you can spread it out, or each missile strike will be devastating. The challenge is usually not to fight a meat-grinder war of attrition, but to crack some seemingly impregnable fortress. What develops is an engrossing game of twelve-dimensional rock, paper, scissors as you figure out just the right moment and location to send in your armour, your air force, your artillery, your infantry.

There are other neat little things. If you fight in woodland, the trees catch fire and the fire spreads and hurts nearby units. The Nod artillery makes craters that are actually depressions in the landscape, not just cosmetic scars. Careful where you put your flame tanks; they will incinerate your own guys if they are standing in the wrong place. These neat little things were abandoned in subsequent C&C titles.

It is annoying, of course, to be limited to a production queue of just five units. Until it isn’t. You get used to it, and you realize that it has freed you up to really think about what you’re building. Armies stick to a manageable size and you have an incentive to preserve them. The five-units thing is a limitation which in effect frees you up.

What I like best is writing about something that you both love and hate – or that you simply feel others have overpraised or over-criticised. It’s satisfying to identify where the good and bad sides of a thing fit together like yin and yang, when the great and the gammy mutually constitute each other, when you couldn’t have the one without the other. It’s equally satisfying to talk about excesses and excrescences, unforced errors and unexpected flashes of brilliance. Best of all when the thing you’re talking about is not ‘high culture’ by any definition, but a vulgar-arsed text that was consumed by tens of millions of people even as it went completely unnoticed in newspapers and academia.

Such a text is Tiberian Sun. I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that it was experienced by more people in its day than many earnestly and widely reviewed Oscar-nominated movies of the same era. The kids playing it then, aged in or around thirteen, are in their thirties and forties now, voting and operating forklifts, approving loans and being approved for loans, or not, and having kids and colonoscopies. Grown-up stuff, far away from the visceroids and Tiberium fields. These posts on Tiberian Sun are for those people, and I hope it has given them the satisfaction of excavating long-neglected recesses of their own minds.

We’ve got a guest post for you today, a review of Netflix’s Gundam: Requiem for Vengeance by freelance writer Charlie Jean McKeown.

Stories and machines are ultimately driven by people, yet Gundam: Requiem for Vengeance lacks the personality needed for the gritty mecha war drama it tries to be. Since its 40th anniversary, the Gundam franchise has been boasting ambitious projects like SEED Freedom (2024) in theatres, Witch from Mercury (2023) on TV, and in gaming Gundam Evolution (2022). (i )

This new Netflix series follows Zeon soldiers- the usual antagonists- in the closing months of the ‘One Year War.’ It’s an attempted love letter for Gundam fans, with a touching homage to the original 1979 show in its opening titles and what must have been a laborious effort to give the classic mecha designs such glorious detail. However, Requiem has little identity of its own; it has little to offer old fans and nothing accessible for new ones. More disappointingly, it does open up genuinely interesting themes which could have given the show some life if they were navigated by decent characters.

Requiem actually inverts some of Gundam’s most central themes; empathy becomes vengeance, and our protagonist is an enlisted mother rather than the usual child soldier. ‘Time’ is not a new theme for the franchise but had never received the same attention it enjoys here albeit with some overly-obvious motifs. The survival element of other Gundam series is heightened in Requiem too, as we watch the losing side struggle against a war-winning weapon. These themes, though, are only minimally engaged with. While one could blame this on the many action scenes, Gundam has always used battles to deepen its narratives rather than merely embellish them. Furthermore, Requiem still has plenty of peaceful moments in its three-hour runtime. The fault is really found in the show’s repetitive exposition soaking up what should be time spent on challenging characters so that they may develop and investigate these concepts.

All of this culminates into the most disturbingly mishandled theme of Requiem: nationalism. Mirroring the Cold War narrative of Nazi Germany (ii), Zeon had always been presented as an evil fascist regime with ordinary soldiers fighting for their homes. Interestingly, the One Year War – the definitive conflict of the franchise – is renamed here as ‘the Revolutionary War.’ Is this how the fascist Principality of Zeon sees itself? Do they view the One Year War the way Confederates saw the American Civil War? It’s a fascinating angle to investigate. However, it feels like Requiem takes up a ‘both sides matter,’ approach, with no real discussion of Zeon’s war crimes (wiping out half the Earth’s population, for instance). Instead, our apolitical protagonist is “just following orders.” While her final monologue is clearly intended to convey a lesson she learnt, it gives us a rather warped justification for continuing to fight under a swastika-esque banner.

While the writing is poor, Requiem’s establishing shots want you to know money and effort went into making them. Requiem is Gundam’s first CG animated production since MS IGLOO (2004), and the improvement in quality is staggering. By tightening their dimensions, the old mecha designs remain credible in today’s science fiction scene while the body language of these giants conveys a surprising degree of emotion. The facial animations are unfortunately less expressive, and to come across they often rely on the wonderful new soundtrack provided by award-winning composer, Wilbert Roget II. Netflix’s first Gundam production does look lovely as a whole, but its writing encourages little confidence in the live action film they announced in 2018. I doubt Requiem will see a second season, which is a terrible shame given its potential; if the writers could make some course-corrections in a new season and rummage through those ideas they raised, then Gundam: Requiem for Vengeance could be forgiven for these first six dismal episodes and actualise its own distinct identity.

(i) While Evolution was closed down in a year, it gave Overwatch 2 a little competition in the hero-shooter market

before collapsing under its embarrassing micro-transactions.

(ii) A narrative, it should be noted, now being revised by historians who are acknowledging the Wehrmacht’s

complicity in war crimes.

When I was 11 or 12 – or maybe it was some older and more embarrassing age – there was a field near my house that me and my friend called the Tiberium Field. You had to dash across it in twenty seconds flat, otherwise Tiberium poisoning would kill you and turn your body into a visceroid, an aggressive and indestructible blob of human tissues. In our heads, we were in Command and Conquer: Tiberian Sun.

So far, so nostalgic. This is a post where I talk about a 1999 strategy game, maybe to recapture the remembered leisure and innocence of the childhood that surrounded it.

But I never got past a few missions of Tiberian Sun, never owned my own copy, and I like it a lot more now than I did back then. If we’re talking nostalgia, I was always more of a Red Alert guy (who could have guessed?). At the time I thought Tiberian Sun was, in comparison to Red Alert 2, drab and self-serious, with a clumsy interface and confusing missions. Earlier this year when I bought the whole Command and Conquer back catalogue for a tenner, I didn’t expect that this would be the game I spent the most time on, the one where I actually finished both campaigns, the one that would haunt my imagination.

So this is not all nostalgia. Something else is going on here, and I’m going to try and find out what. And even within the nostaglia, there’s the question of how this game worked its way into my imagination in such a way as to turn the grass of that neighbourhood field into an expanse of deadly and valuable green crystals.

So how did this game warp my young (and not-so-young) mind?

The first point in favour of Tiberian Sun (henceforth TS) is its setting. The world of the original Command and Conquer was sort of improvised. The developers said, let’s have something like the spice from Dune 2 – it works so well as a resource-gathering feature – but transplanted to another setting. The result is Tiberium, a strange green crystal native to some alien world which has begun to spread over Earth’s surface. There are two factions: the Global Defence Initiative (GDI), a one-world military defending the status quo, and the Brotherhood of Nod, which is part-Tesla, part-ISIS, part Comintern, and obsessed with using the Tiberium for obscure ends. My impression, having played only a little of the original C&C, is that whatever worldbuilding there is starts to peter out around there. The setting is just an excuse to have a war game on the Dune 2 formula. (I’ve talked about the Red Alert spin-off elsewhere.)

Tiberian Sun takes the worldbuilding more seriously. A couple of decades after the first game, the Tiberium infestation has advanced, and Planet Earth is now terminally sick. GDI and Nod are still fighting over ruined cities and land choked with alien crystals and alien weeds, skies torn by ion storms, poisoned air, mutated genetics. For more on the setting and its applicability as a prophecy for our times, I recommend this article from Eurogamer by Robert Whitaker.

Tiberian Sun captured that late-1990s sense of some vague impending doom. But in 2024 it offers a strange kind of relief. You can retreat into the barren comfort of a world that is already destroyed, where there is little to save. There are unexpected inheritances from Dune: like in Herbert’s book, the ground beneath your feet is more than a setting, it’s an actor with powers of life and death over the fragile humans and machines crawling on its surface.

The applicability to climate change and global warming (which we all absolutely knew about in the 1990s even though those in power did nothing) are obvious. It’s a metaphor for our times in another way too. GDI are coded as “good” but we never see them actually doing, or even promising, anything good. They never help anybody or change anything, until the Forgotten twist their arms. We side with GDI only because Nod are obviously and extravagantly worse. Yes, GDI is Harris and Nod is Trump. Neither side offers a way out of war and ecological destruction. But Nod at least offers its supporters the shallow pantomime of its rituals and chanting and bloody spectacles.

The setting itself tells a story: when we move our little men across the map, we see ruined high-rise buildings, contrasted with space-age-looking new settlements with solar panels and bunkers and greenhouses: the civilian world has retrenched into smaller and more resilient communities. Meanwhile war has advanced as a science. It’s all laser guns and visored helmets, giant walking battle mechs, cyborgs, explosive throwing discs, orbiting battle stations. Humanity is spending and innovating to fight more effectively, even as we have less and less to fight for. While the Red Alert setting just pits an evil faction against a good faction, Tiberian Sun (TS) takes place in a world that is messier and more ambiguous. In Red Alert, we don’t know why the Soviets are attacking the status quo. In TS, we don’t know why GDI are defending it.

Videogames then were violent, militaristic, imperialist – not in a the conscious and blatant way that Call of Duty is now, but as it were by default, by reflex. C&C is no exception. The GDI versus Nod struggle is at base the same old Imperialism versus Third World struggle, with the legitimate struggles of the global majority (“disenfranchised nations” seduced by Nod) packaged as evil fanaticism. In TS it is less explicit, filtered through layers of deniability in the worldbuilding, but we get signals, such as that the villains in Tiberian Sun have names that are Arabic, Latin and Slavic (he’s literally called ‘Slavik’). The Latino baddie is a drug smuggler who menaces the southwestern United States, playing into racist tropes. We see one South Asian guy in the ‘Global’ Defence Initiative, but the rest of the goodies are Americans.

The music is not as conspicuously brilliant as that of Red Alert 2 but it has a greater range. There are moments of foreboding (‘Valves’) and loss (‘Approach’). If Red Alert 2 is a violent cartoon, Tib is a 1980s-90s action sci-fi movie – the vibe, to me, is sort of like Terminator 2, Aliens and Paul Verhoeven.

The melancholy themes probably belong to the third faction in Tib – unplayable and lightly sketched, but essential to the story (I suppose if GDI is Harris and Nod is Trump, they are Jill Stein or Cornel West). This is a loose confederation of clans who call themselves The Forgotten. They are people mutated by Tiberium exposure – insulted and belittled as ‘shiners’ by GDI and Nod alike, distrustful of GDI due to past atrocities, persecuted and imprisoned by Nod. They are few but they are pretty lethal in a fight.

The Forgotten are the conscience of this story. In the GDI campaign, it is only by overcoming prejudices and working with the mutants that GDI can defeat Nod. In the Nod campaign, you prevent any possibility of an alliance between GDI and mutants through a nasty trick. There’s more going on here than is usually the case in this series.

In Part Two of this review I’m going to be looking at two other strengths of Tiberian Sun – the cutscenes (you heard me) and the gameplay. But before I move on I want to comment on the 2007 sequel, Tiberium Wars and its expansion Kane’s Wrath (I haven’t played Tiberium Twilight). What I have to say about Tiberium Wars (TW) underlines what I’ve just said about TS.

I’ve played a lot of TW and enjoyed it, but it doesn’t have the same grip on me as its 1999 predecessor. And I don’t think it’s just nostalgia.

The graphics and the smoother interface are a huge upgrade on TS, marking a rapid development in just 8 years. The story is solid, far less silly, and it’s all in all a lot of fun to play. But the setting doesn’t feel as real to me, and I think I know why.

Tiberium Wars leans with dispiriting heaviness into a ‘Global War on Terror’ framing. Magazine ads for the game talked about fighting terrorism. Technologically, GDI has been downgraded – no more stomping robots. This is explained in-game as being due to budget cutbacks, but the effect of it (and probably the intention) is to make everything look a few-score degrees more like Iraq or Afghanistan, or some near-future 9/11. The expansion Kane’s Wrath thankfully leans back the other way, and was clearly crafted by people who loved TS.

TW’s setting is retconned so that the Tiberium-infested world is divided up into uninhabitable Red Zones, Yellow Zones which are in a state of social collapse, and Blue Zones which are stable and prosperous. This is a marked contrast to Tiberian Sun, in which everywhere – Egypt, the USA, Norway, Germany, Britain, Mexico – was one of two things: a Yellow Zone or a snowy Yellow Zone. In TW, the Blue Zones we see are all either in the USA or in Germany. We always see them menaced and under assault. The first few missions are a bizarrely close remake of Red Alert 2, with the baddies invading hallowed American landmarks like the White House and the Pentagon (No! Please don’t destroy the White House or the Pentagon! Anything but them!). The Imperialism vs Third World framing is much more obvious and open. It’s no accident that the Forgotten are left out of the story of TW – they appear only as an Easter egg and they talk like super mutants from Fallout.

At base the reasons I don’t like it as much are political; I think it’s a shitty way to portray the majority of the human race, as if they have nothing better to be doing than besieging and menacing whatever dull place you live. But you don’t have to agree with that to see that these are two very different types of story and setting. Tiberium Wars is the same old C&C story about protecting the status quo. Tiberian Sun has more depth and ambition.

To receive an email when Part 2 of this article goes live, type in your email below:

A Demon in my View (1976), The Face of Trespass (1974), Dark Corners (2015)

My first knowledge of Ruth Rendell was probably of seeing her name on library paperbacks around the house when I was a kid. I didn’t read her stuff until many years later after reading some glowing endorsements of her by authors I like. The only title of Rendell’s available that day on my library audiobook app was one called A Demon in My View. So I went ahead and downloaded it. That was back in March; by August I had read three out of her many dozens of novels published across nearly fifty years. I’ll give a run-down of each of the three, in the order in which I read them.

I should add that I listened to these novels as audiobooks, performed by Julian Glover (A Demon in my View) and Rick Jerrom (The Face of Trespass and Dark Corners), who both do a great job.

By the way, the reviews below contain some spoilers.

I was hooked on this story, right from the fucked-up start to the ironic and satisfying finish. A Demon in My View is about a man who once terrorised his fictional London suburb as a serial killer, but who has settled into a safer middle age by getting his kicks repeatedly ‘murdering’ a mannequin who lives in the neglected cellar of his shared, rented house.

The killer is a despicable sadist but Rendell manages to get us into his head, convinces us to feel an iota of sympathy for the wretch. He was raised by an aunt who judged him because he was born outside wedlock. There is something pitiable in his uptight, timid, neurotic narrative voice. But this timidity is the flip side of his murderous compulsions; he has a drive to feel power over others by causing fear and pain. The most horrifying example is the flashback scene involving the baby, which nobody who reads this book will ever forget until the day they die.

The whole story revolves around the tension between his hidden world and the intrusive realities of a shared housing arrangement. What we’ve got here is a story that’s fundamentally about housing, a theme that is important in all three books of Rendell’s that I have read.

The story is firmly rooted in its time and place, not in a way that dates it but in a way that enriches it. A new flatmate moves in; he has a very similar name to the secret serial killer, which provides all kinds of opportunities for confusion and subterfuge. In the 1970s, when this story is set, the post was crucial to people’s social lives and communications, and the only phone in a shared house word likewise be a shared one. The new arrival is really our main narrator and protagonist, but the long agony and final comeuppance he inflicts on our serial killer is unintentional and indirect.

Here is a writer, I thought, who can keep me in suspense, craft a believable social and cultural world, invest me in the practical limitations of comms in the 1970s, and horrify me with a rounded portrait of a human monster.

The Face of Trespass is about a young writer living semi-feral in his friend’s cottage on the wooded margin of London while his girlfriend, a married woman, tries to convince him to murder someone. The story is bookended by a brilliant introduction and conclusion which involve a completely different cast of characters but which provide a resolution to the story. The day is not saved, but at least we get a significant consolation at the very end and from an unexpected source.

Murder is of course not relatable. But Rendell surrounds it, links it intimately, with things that are closer to our everyday lives. There’s lust, greed, envy. Again, housing. Scarcity of funds. An elderly mother living in another country and slowly dying; linked to this, a stepfather with emotional baggage and a language barrier. Aunts and old school friends. Pets. Obligations.

Apart from the aforementioned bookends, we stay in the point of view of the main character, the struggling young writer. Everyone reading The Face of Trespass will be able to see clear as day how our main character is being set up. I found this a little frustrating; we hate protagonists who are fools, who walk blithely into trouble. But in the end all was forgiven. Rendell’s playing a deeper game. The girlfriend is out to set him up – that’s obvious. What’s not so obvious (though all the clues are there) is (spoiler alert) how he will get out of it in the end.

Even more so than in A Demon in my View, seventies comms are central to the novel; much of it revolves around people waiting by phones.

One surprising highlight of this novel is the stepfather. I don’t know if I would pick up a book based on some blurb about a stepfather-stepson relationship. But the murder/mystery/thriller genre here serves as a vehicle for an amusing and, in the end, quietly moving sub-plot.

Dark Corners was Rendell’s last novel, written decades after the other two above. It is still very good and gripping, but rougher around the edges.

At one point in the novel the main character, again a writer, laments that the characters in his work-in-progress all speak like they come from the middle of the century. This must be Rendell’s little dig at herself; the characters speak and often act like they just walked out of the much more affordable London of A Demon in my View. Modern things like the internet are mentioned a lot, but usually bracketed with some comment like, ‘Johnny supposed that this was the way things were these days’ – as opposed to thirty years ago, before Johnny was born.

Like The Face of Trespass, pets and vets come into it. But it’s housing that’s at the heart of the novel, in ways that highlight how the issue has changed radically since the 1970s. The landlord in A Demon in my View is a rather greasy and selfish character; the landlord here is a struggling writer renting out the upstairs of his late Dad’s house so that he can work full-time on his novel. But his tenant proves to be far more trouble than he’s worth. He refuses to pay the rent and refuses to move out.

Meanwhile a rudderless young woman finds her rich friend dead, and proceeds to occupy her apartment and wear her clothes. But impersonating a rich person, like taking in a tenant, proves to be more trouble than it’s worth. In this case, that’s putting it mildly: she is brutally abducted and held for ransom.

These two characters are a few degrees of separation from one another and only meet toward the end, in a very fateful encounter.

Again, the literal setting is London – and there’s a powerful sense of place – but on a deeper level the setting is the human mind struggling with fear and longing. Rendell’s home turf is psychology. As in A Demon in My View, we see the murderer from the inside out, and he is wretched and pitiful. Unfortunately, like The Face of Trespass but more so, we have a struggling writer who spends a chunk of the novel just frustrating us with his passivity and short-sightedness.

There is a third, and subordinate, storyline about a retired man who rides buses for fun (Yes, a third storyline. All three of these books are very slight, but it’s amazing how much is crammed into Dark Corners). This storyline is fun, but its culmination is the retiree very suddenly foiling a terrorist bomb plot. Rendell has this humane side that allows her to write stories where a modest older man becomes a hero thanks to his eccentric hobby, and that is satisfying. The problem is that the bombing has nothing to do with anything else in the novel, and has no impact on subsequent events.

This is one of many strange improbabilities and coincidences that, to my mind, constitute gaps in the fabric of the novel. It’s all the more obvious when compared to how tight-knit the other two books are. It appears the novel is kind of about coincidences – stories criss-crossing in a Pulp Fiction kind of a way. Coincidence played a role in the others, but to a lesser degree, and with more subtlety, and to better effect.

Dark Corners is readable and satisfying, but rough and flawed. In addition to its other virtues, it is rough and flawed in interesting ways.

First and foremost, these were gripping thrillers that passed the time for me while I did chores or drove. But the contrasts between the younger writer and the older, between the younger London and the older, added a great deal to the experience for me.