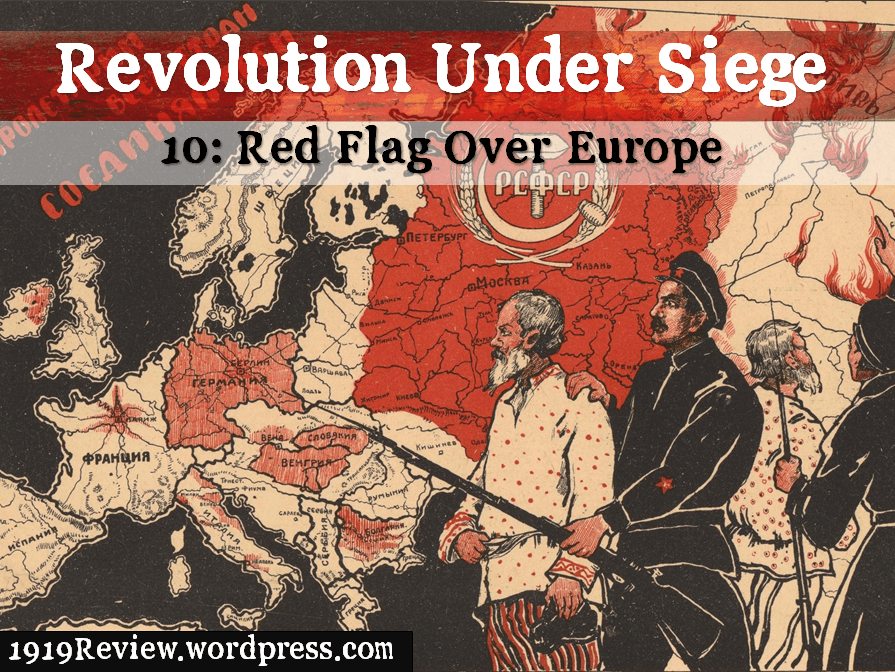

As 1919 began, the vast expanse of Siberia was occupied by an array of factions and warlords. This post introduces the reader to some of the White warlords of Siberia, and follows Admiral Kolchak’s Spring Offensive.

Revolution Under Siege is back for a second series, tracing the epic events of 1919 in the Russian Civil War.

Before the October Revolution, when Russia was still fighting in the Great War and desperate for new recruits to replace the millions dead and wounded, the Provisional Government sent two cavalry officers to the furthest eastern reaches of the empire. Their mission was to recruit a regiment of Mongols and Buriats, horse nomads of the steppe.

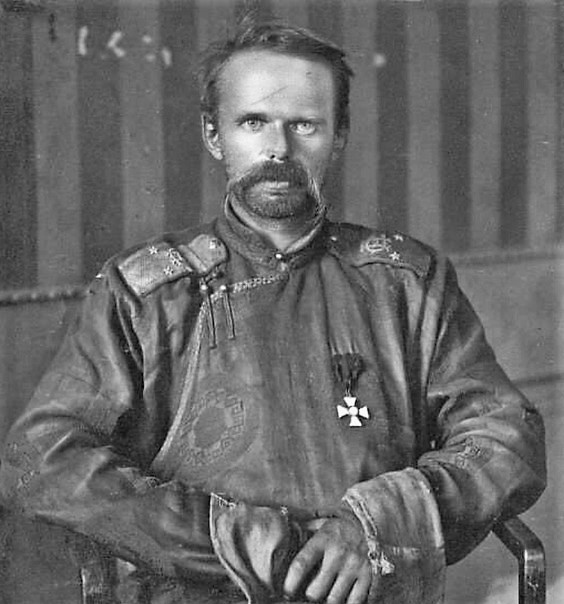

Captain Grigori Semyonov was a Cossack of Buriat origins himself. He was ‘a thick-set character with moustaches shaped like a water buffalo’s horns.’[i] Semyonov’s companion was Baron Roman von Ungern-Sternberg. He was a Baltic German aristocrat from Estonia, but he was already an old Asia hand. He had travelled in Mongolia, he idolised the warriors of the steppe, and on this journey he wore a bright red Chinese jacket and blue trousers. The young baron had the thousand-yard stare. He had served in a regiment which had suffered 200% casualties in the early part of the war. But he was happy during the war years – never happier.

At the start of 1918, the mission consisted of Semyonov, Ungern and six other guys with their horses. Meanwhile back west in the capital, the working class, organised in the soviets and led by the Bolshevik Party, had taken power. The government that had sent Semyonov east no longer existed. The war into which the Mongols and Buriats would have been thrown was, for Russia, over.

But the sabres of Semyonov and Ungern did not rest. They joined the counter-revolution and became warlords of Siberia. To them, the Provisional Government had been bad enough, but the Revolution was an atrocity. The workers and peasants must be crushed.

Their first uprising was at Verkhneudinsk, just a week or two after the storming of the Winter Palace. They were backed by Transbaikal Cossacks, but they failed, and fled to China.

On New Year’s Day 1918 they crossed back into Russia. Their force of 8 soldiers held a train and lit it up to bluff that they had bigger numbers; in this way they disarmed a Red garrison of 1500.

Meanwhile a Bolshevik sailor and commissar named Kudryashev was on his way to Vladivostok with government money. He and his companions held a New Year’s party on the moving train, and Kudryashev got so drunk he forgot to change trains. The mistake proved fatal.

They were halted near the Chinese border and Ungern led soldiers into the carriage full of celebrating Reds.

Ungern fixed his cold, piercing eyes on Kudryashev and demanded: ‘Deputy Naval Commissar, that’s you?’

‘Baron Ungern looked through his papers, then made a cutting gesture with his hand to his companions. “As for these shits,” he added, pointing to the others from Kudryashev’s party, “whip them and throw them out.”’

Kudryashev was taken out and shot dead in the snow.[ii]

During the six months following the Revolution, Semyonov and Ungern twice rounded up sizeable forces in Manchuria – Mongols, Buriats and anti-communist refugees. They twice invaded Siberia, and were twice driven back across the border into China by the Red Guards.

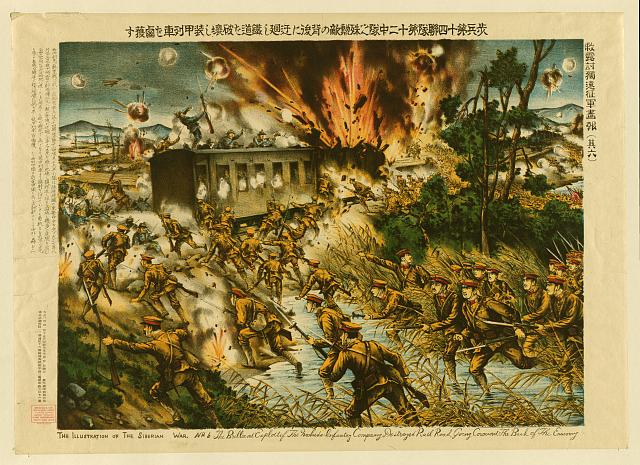

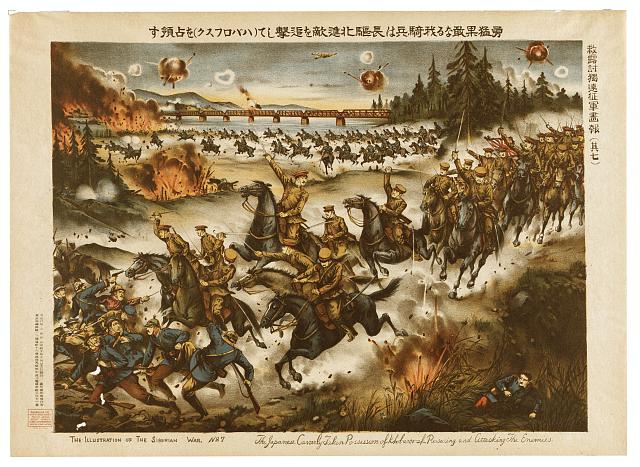

The fortunes of Semyonov changed thanks to the Allies. First, Semyonov received a load of money from Britain, France and especially Japan, allowing him to hire Chinese mercenaries and to arm and equip his volunteers. Thus he built a force he called the Special Manchurian Division. Second, Semyonov and his Division were on the brink of annihilation when they were saved by the Czechoslovak Revolt of May 1918. Last, when the Special Manchurian Division invaded Russia for the third time in July 1918 it was with massive Czech and Japanese assistance.

A few months earlier, Semyonov had been alone except for a handful of volunteers and an eccentric baron, on a mission from a government he despised. By the end of August, he was dictator of the Transbaikal.

Covering more than 600,000 square kilometres, the Transbaikal region is only a little smaller than Texas. It stretches from Irkutsk in the west, a town on the shores of the vast Lake Baikal, to the Pacific port of Vladivostok in the east.

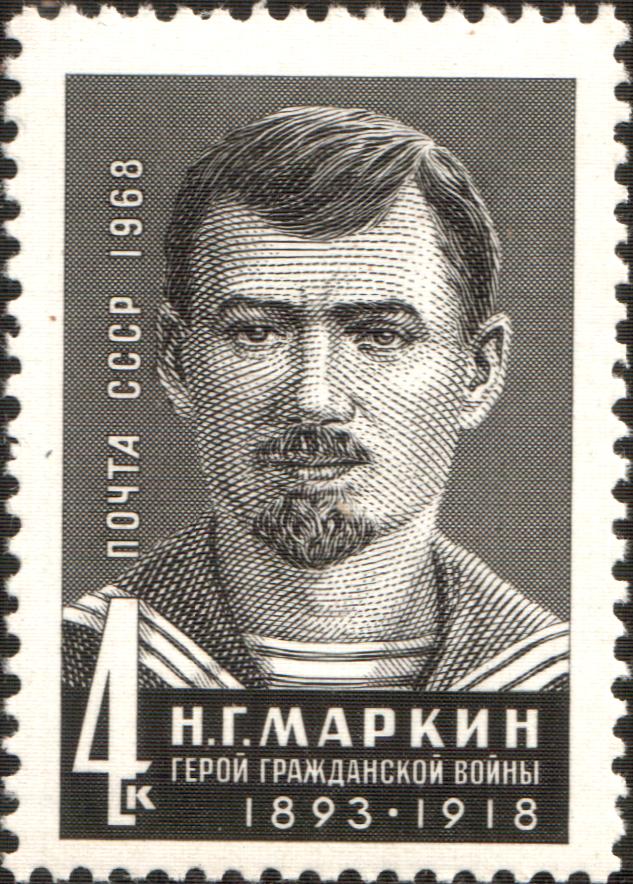

Semyonov

In late 1918 and through 1919 Semyonov ruled from the town of Chita under the slogan ‘For Law and Order!’ while his officers enjoyed cocaine and the company of sex workers. The night life of the city was made livelier by Red partisan assassins lurking in the alleyways.

Semyonov wished to create an independent state called Daurskii and allegedly awarded himself the title of Grand Duke. But in the words of a Chinese newspaper he was ‘Caliph for an hour and a toy of the Japanese.’[iii] He was more or less subordinate to the Japanese state, which had 70,000 soldiers on his territory along with British, French and US detachments. All the same, he lived like a king. He had thirty mistresses who lived on what was called ‘the summer train’ along with a great store of champagne and an orchestra made up of Austrian prisoners. In June 1918 he was elected ataman (warlord) of the Transbaikal Cossacks.

Semyonov used to boast that he could not sleep easily at night unless he had killed someone that day. It was not an idle boast as his victims numbered in the thousands.[iv] By his own account, he personally supervised the torture of 6,500 people.[v] In this last detail Semyonov was not an outlier (though in other respects he certainly was). According to one foreign observer, White Guard officers ‘remarked almost daily that it was necessary for them to whip, punish, or kill someone every day in order that the people know who was protecting them from the Bolsheviks.’[vi]

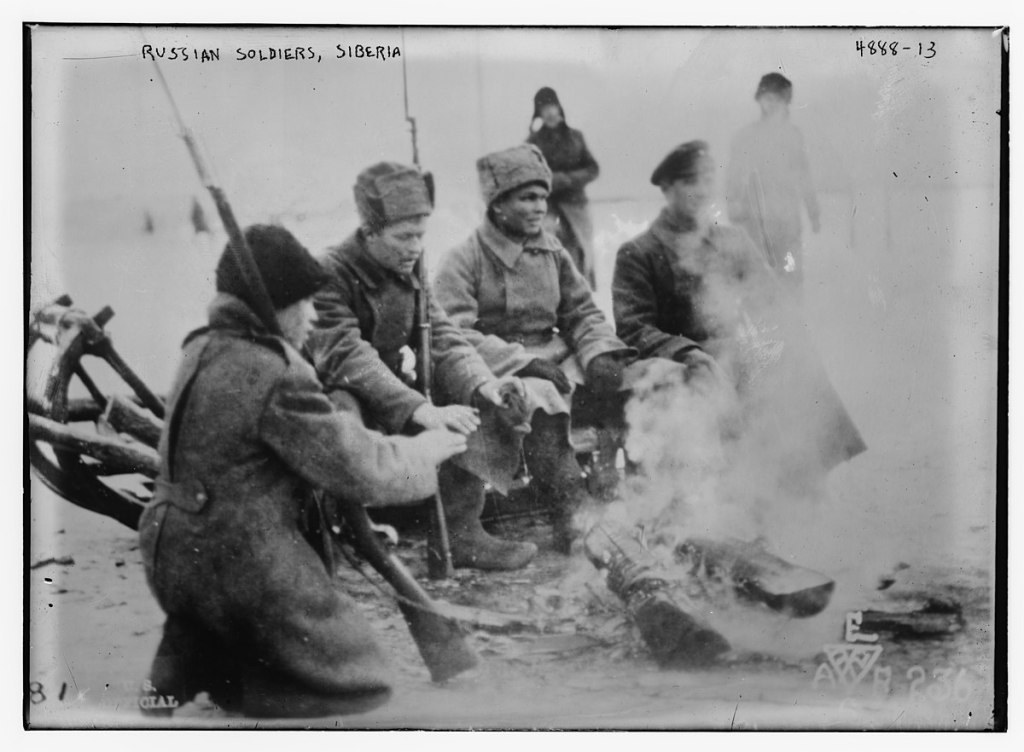

The Transbaikal was sparsely settled. Trains plied the vast empty lands between the towns and villages. Semyonov and his 14,000 men, by Spring 1919, did not generally stray far outside of Chita, where the warlord lived in a compound guarded by artillery. But armoured trains would supply Semyonov’s armies in the manner of Carribean pirates, pulling up to a station and threatening to open fire with naval guns unless food was handed over.

In Siberia, where the towns were like islands, thousands lived on the rails – Palmer says there were ‘hospital cars, headquarters, brothels, travelling theatres, dining cars appointed like opulent Moscow restaurants, libraries, motor workshops, churches, mobile electric generators, printing shops, offices and torture chambers.’ The old pre-revolutionary cadre of railway workers somehow kept everything moving. Secretly they aided the Red partisans.

Then there were the prison trains, cattle cars filled each with fifty Red prisoners of war, which would travel ‘aimlessly from station to station with neither food nor water.’ Whoever was left alive in the cars after a few weeks would be shot.[vii] For example, a train arrived near Lake Baikal on August 4th, crammed with 2,200 captives from the Red Army (taken during the Spring Offensive – see below). ‘Most of the prisoners appear to be sick with typhus, and starving. Several dead were removed from the cars. It seems that there are dead to be removed at every station.’[viii] The eyewitness quoted just now was a US soldier who was guarding the railway line which the Whites were using in this way.

The railways were the primary target of the Red partisans, though they also infiltrated mines and triggered strikes.[ix] The huge distances and deep forests provided refuge to all those who wanted to fight the Semyonov regime, and they lived in camps as big as small towns.

What was the political character of these guerrilla bands? According to Wollenberg:

Speaking generally, we find that the guerrilla movement assumed two widely contrasted aspects, represented respectively by the Ukrainian guerrillas, among whom the influence of the individualistic wealthier peasants predominated, and the Siberian guerrillas, who manifested the peasant-proletarian disciplined character of the movement. Naturally the line dividing these two opposites was by no means a territorial one; indeed, both these guerrilla manifestations often existed side by side, and were often closely woven with one another in the same band.[x]

On Ukraine, more next episode.

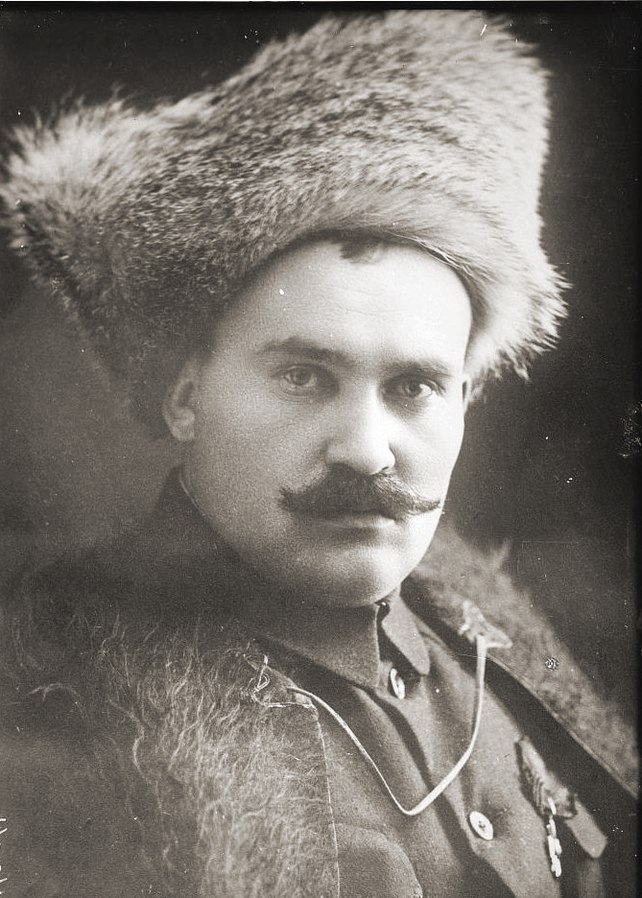

Ungern

Ungern, the baron from Estonia, was now a Major-General under Semyonov. His Asian Cavalry Division, a force which was growing in size to rival Semyonov’s, would be called upon to lash out in reprisal at the villages in the aftermath of partisan raids.

A fort of red stone dominated the border town and railway station of Dauria, and this was Ungern’s castle.[xi] The railway lines were the source of supply for his army and regime; he robbed those who passed through, especially Chinese merchants (for some reason, he hated the Chinese).[xii] The sandy hills near town were scattered with the skulls and bones of Red prisoners who were sent to Dauria, ‘the gallows of Siberia.’

Ungern ran a strange and very personal regime in Dauria. He was cruel to officers, gentle to horses, popular with soldiers. Evening prayer services were probably the most ecumenical to be found in any military base in the world: Orthodox, Lutheran, Buddhist and other holidays were officially celebrated. When typhus came to Dauria, Ungern went into the hospital and killed those infected who were unlikely to recover. He hated paperwork: when Semyonov sent an inspector, Ungern had him whipped and conscripted.

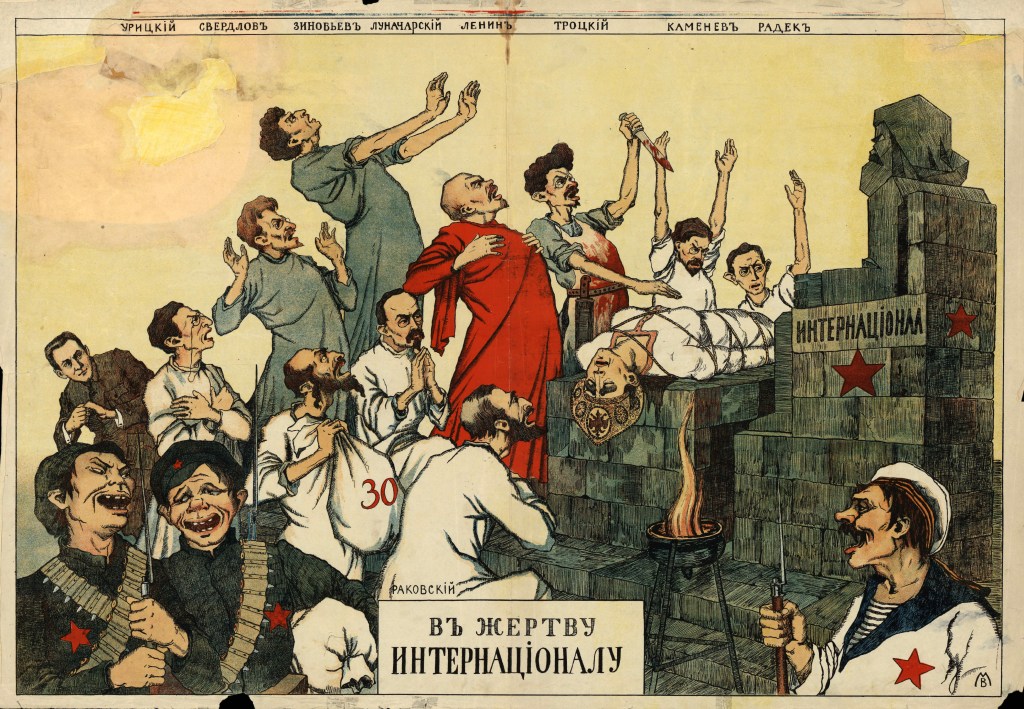

Within the confines of his own blood-drenched and occult moral code, Ungern was apparently austere and incorruptible. He was virtually the only Semyonovite who did not embezzle; on the contrary, he donated his own pay to the men. He did not believe that the Communist International had been founded only in March 1919, but in ancient times in Babylon. He read mystical signs in playing-cards; he admired Mongolians, and believed they practised magic. Semyonov was surrounded by cocaine and champagne; Ungern smoked opium so that he could have mystical visions. These visions anticipated those of Hitler; in Ungern’s words it was necessary to ‘exterminate Jews, so that neither men nor women, nor even the seed of this people remain.’[xiii]

In most respects Ungern was singular. But in his anti-Semitism he was with the mainstream of ideas in the White camp, where the Protocols of the Elders of Zion and the ‘Zunder Document’ circulated widely, where ‘Jew’ and ‘Communist’ were treated almost as synonyms.

With his extreme reactionary views, the mix of weird and contradictory ideas that informed them, his violent nature, his hatred of women (apparently he is what would now be called a ‘voluntary celibate’), Ungern reminds me of one of those mass shooter from today’s United States.

Semyonov and Ungern were not the only warlords of the Far East. Ataman Kalmykov was also an important figure, subordinate to Semyonov. About Kalmykov my sources don’t tell me much except that he was a glorified bandit, and that he tortured and killed his enemies in blood-curdling ways.

The Civil War in the Transbaikal was a diverse affair. We have noted the presence of Czech, British, French and US forces, and of a full-scale Japanese invasion. Most Japanese stayed by Vladivostok; some went as far inland as Lake Baikal. On one occasion, drunk American soldiers beat up a trainload of White Russians. There was much back-and-forth over the borders with Manchuria and Mongolia. Spies reported to Japanese noblemen rather than to a centralised secret service. Alongside Russian settlers were the indigenous peoples of the area such as the Buriats, who fought on both sides. There was also the Transbaikal Cossack Host, the fourth-largest in Russia with 258,000 fighters, along with the 96,000 Amur, Iakutsk and Issuri Cossacks.[xiv]

A Japanese-sponsored conference discussed founding a pan-Mongolian state. It should be obvious that the White Russians were not keen on the idea (‘dismembering sacred Holy Russia…’). Ungern was also against the idea. He only liked Mongolians when they were romantic nomads; he did not like literate Mongolian intellectuals gathering to discuss modern concepts like nation-states.

There were tensions between Mongolian factions. The Karachen Mongols – from Inner Mongolia, today a province of China – grew angry with delays in pay. Two days of fighting raged in Dauria when 1,500 Karachen killed their Russian officers and seized an armoured train.

Kolchak

Moving westward along the Trans-Siberian railway, we leave the atamans behind and approach Kolchak. We saw last series how in November 1918 Admiral Aleksandr Kolchak cast aside the Right SRs and rose to the position of Supreme Ruler of the White cause in Western Siberia. His capital city was Omsk.

Kolchak was not the only Admiral who, in 1919, found himself ruling supreme over a landlocked territory. Miklós Horthy in Hungary found himself in the same position. Landlocked Admirals are, it appears, not just a symbol but a product of collapsing empires.

By the time of Kolchak’s coup, Semyonov had been in power for months. Semyonov felt threatened by this development and enforced a ruthless blockade over Kolchak’s territory. This was like putting his boot on the Admiral’s jugular; the Trans-Siberian Railway was the narrow blood vessel connecting Omsk to the Pacific Ocean, and to the Allies.

An eyewitness recalled Kolchak’s fury: ‘If Ataman Semenov had fallen into his hands now, the Admiral would not have hesitated to have him shot on the spot.’[xv]

After negotiations and a standoff, Semyonov not only lifted his boot but agreed to place himself under Kolchak’s leadership. Later Kolchak would formally and openly acknowledge Semyonov as the next-highest leader of the White cause in Siberia.

They were never happy allies. While Semyonov was a proud and open reactionary, Kolchak was in a position where he had to play a more delicate game. While Ungern was dragging Chinese merchants off trains and Semyonov was swigging champagne with his mistresses, Kolchak was trying to conquer Moscow. Kolchak’s officers were the kind of men who would challenge one another to duels and slap their soldiers in the face, but Kolchak himself had to present his regime as more modern and democratic in spirit. He needed Allied support, and he needed to build up a mass regular army recruited from among ordinary peasants. Everything east of Irkutsk was a bloody embarrassment and in many ways a liability to Kolchak.

But in other ways the Supreme Ruler in Omsk relied on the warlords beyond Lake Baikal. According to Palmer, it was to the realm of Ataman Semyonov that many Red prisoners-of-war were sent, never to return. Those of Kolchak’s faction believed, or at least claimed to believe, that there was a system of prison camps east of Lake Baikal, but there was no such thing. There were death trains, death barges, firing squads, sabres, even ice mallets. All this played ‘a critical, gruesome part in the White infrastructure’[xvi] though we should note that a greater number of Red prisoners were simply recruited as (very unreliable) White soldiers.

In addition, Kolchak and co had no idea how far they could push Semyonov, because they did not know how committed the Japanese were to him. So they didn’t really push him at all.

At least one author has claimed that Ungern was not representative of the White cause.[xvii] This is true enough; Ungern was really only representative of Ungern. But pointing to the prison trains and the mass graves, Palmer argues that the two depended on each other.

This contrast between what it was and what it pretended to be defined Kolchak’s regime. Its government departments were well-staffed and built on an all-Russian scale, but underneath there was very little in the way of actual services being delivered or concrete tasks being carried out. It was, to adapt a phrase, too many atamans, not enough Cossacks. Its military had a lot of top brass with impressive titles, but many were young, junior officers who had no idea how to command tens of thousands.

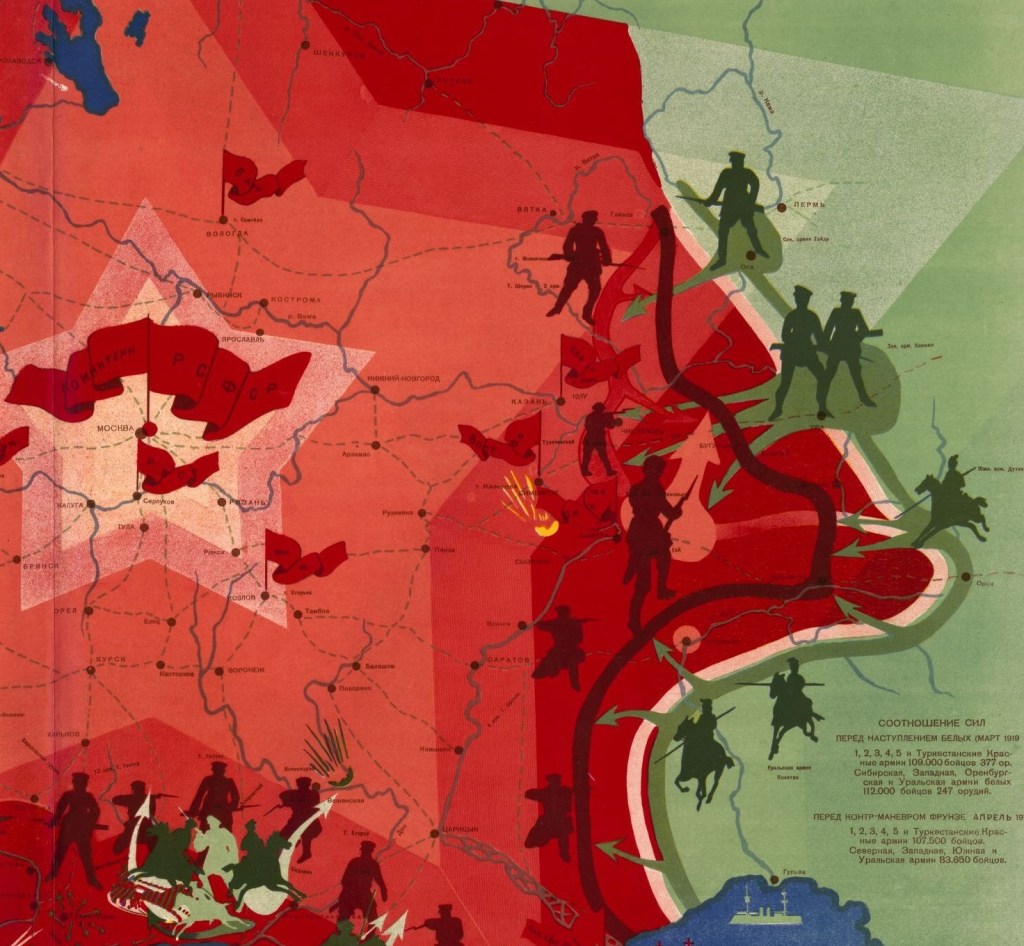

The Spring offensive

In early 1919 the forces of Admiral Kolchak had plenty of prisoners to dispose of. They went on the offensive and for months enjoyed extraordinary success.

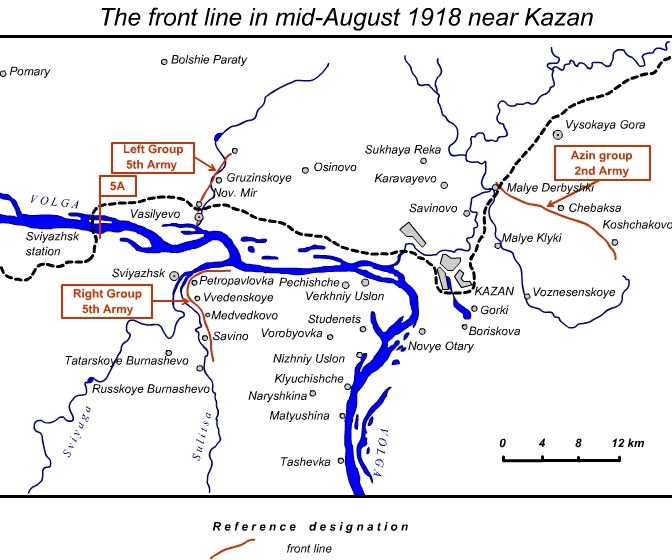

In late 1918 the Komuch regime on the Volga had collapsed under the pressure of the Red Army, the key battle taking place at Kazan. In the winter of 1918-19, Five Red Armies advanced into the Ural Mountains. In January 1919 Lenin envisaged this Eastern Army Group taking Omsk within a month. It was not to be.

Perhaps he should have taken the ‘Perm Catastrophe’ as a warning. I mistakenly wrote in a previous post that after Kolchak’s coup the Czechs played little further role in the war. But it was the Czech officer Gajda who attacked the northern extremity of the Red front at the end of 1918, seizing the town of Perm and throwing the Red Third Army back nearly 300 kilometres.[xviii] Five Red Armies – but were they proper armies in reality, or only on paper? If Gajda could devastate Third Army so easily, Kolchak had reason to believe that the whole Red war effort was ready to crumble under serious pressure.

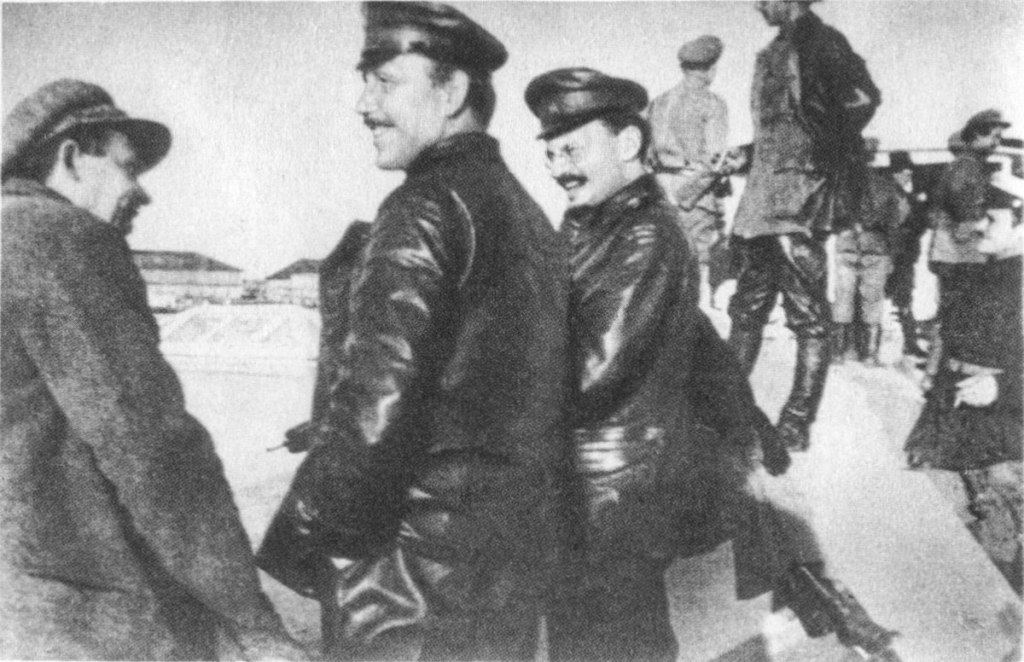

The Admiral was a sincere and devoted leader who made a point of visiting the frontlines and dispensing gifts to the soldiers. He had that ‘lean and hungry look’ that Shakespeare noticed in certain political figures: ‘he thinks too much… such men as he be never at heart’s ease.’ He was tormented by the dilemmas and pressures of the situation, shouting at his ministers, throwing things around his office, gouging at his desk with a knife. Punishing the furniture was easier than tackling festering problems such as the ‘warlordism’ of Semyonov.

He needed soldiers. Here in Siberia the land question was less pressing, so the peasants were not as hostile to the Whites as elsewhere. But the trained veterans of World War One who had returned to civilian life in Siberia were of no use to him; the war had made them cynical, and in the trenches they had been ‘infected’ with Bolshevik propaganda. From Kolchak’s point of view they were rotten. It was necessary to conscript tens of thousands of younger men, too young to have fought in the ‘German War’ or mutinied during the Revolution. But it would take time to train them up.

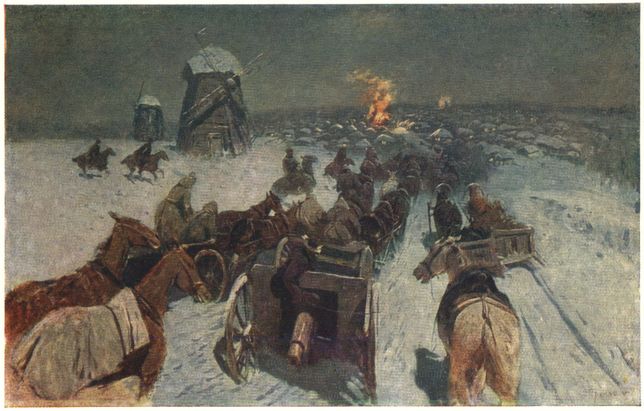

Kolchak did not have time. At the start of 1919 it looked like the Allies were ready to sign a peace treaty with the Soviets. To get support and aid, Kolchak needed to show that he stood a chance of crushing the Revolution once and for all. So he needed to launch an offensive, and he needed to do so in the narrow window between bleakest winter and the rasputitsa, the season when every gully would be a roaring torrent and every artillery piece would be axle-deep in mud.

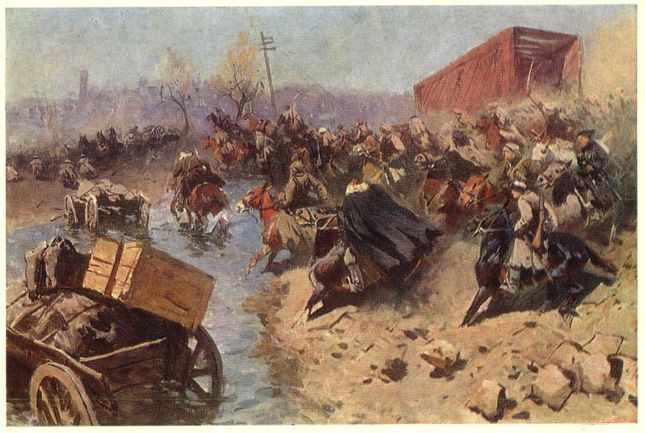

The White forces exploited this narrow window of time with brilliance. On March 4th they advanced through the frozen Ural passes on skis and sledges. On the middle part of their front the Whites set their sights on Ufa. They faced not some rabble of Red Guards, but the Fifth Red Army, tempered at the Battle of Kazan. Nonetheless by March 14th Ufa was in White hands.

The young conscripts were still back at Omsk being trained up. This offensive was made by Kolchak’s Siberian Army of officers and Volunteers, bolstered by the incorporated remains of the Komuch People’s Army. So this was a victory of modest numbers against greater numbers.

By the end of April Kolchak’s army had taken a territory the size of Britain, populated by 5 million people. In May, a White officer stood on a height in the re-conquered city of Ufa and looked west over the Belaia river.

Beyond the Belaia spread to the horizon the limitless plain, the rich fruitful steppe: the lilac haze in the far distance enticed and excited – there were the home places so close to us, there was the goal, the Volga. And only the wall of the internatsional, which had impudently invaded our motherland, divided us from all that was closest and dearest.[xix]

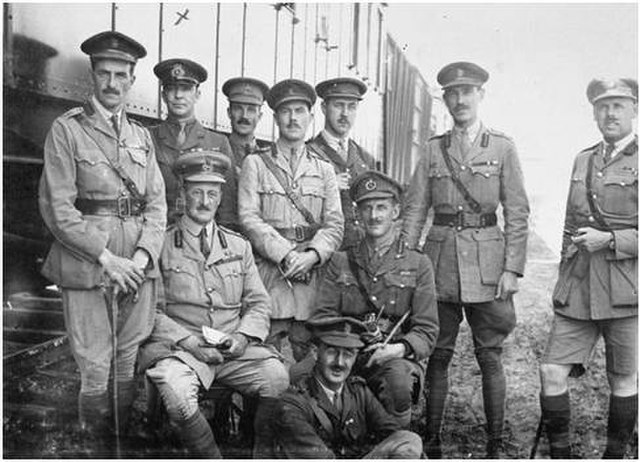

There is a profound irony in the White Guard complaining about the internatsional. At that moment, behind his back to the east the railway was held by a counter-revolutionary international: Japan, the Czechs, the US, Britain, France. Allied battalions garrisoned key Siberian cities for Kolchak. The British at Omsk were training up some of the conscripts. If the White officer carried a rifle as he looked westward from Ufa, the bullets in that rifle were of British manufacture; General Knox at Omsk, Kolchak’s best friend among the Allies, claimed that every round fired by the Siberian Whites since December 1918 had been made in Britain, delivered by British ships at Vladivostok, and transported into the interior by British troops.

The flow of supplies had increased. The Spring Offensive had succeeded in terms of land conquered and as a signal to the Allies. Now the peace proposals were a thing of the past, and the Allies had committed themselves with renewed energy to the task of strangling the Russian Revolution. Between October 1918 and October 1919, 79 ships arrived at Vladivostok carrying 97,000 tons of military supplies. This meant around 1.27 million rifles, 9631 machine-guns and 622 artillery pieces.[xx] That is to say nothing of rolling stock, uniforms, greatcoats, boots, etc. Even though a portion of this must have been absorbed by looting and black-marketeering as it passed through the hands of Semyonov, these were vast supplies for a White Army numbering only around 100,000.

But next to what the Whites hoped for and the Reds feared, the role of the Allies fell short. When the Soviet war commissar Trotsky heard of Winston Churchill boasting about the ‘crusade of fourteen nations’ against Bolshevism, he responded with mockery. The Whites, he pointed out, had been hoping for something more like fourteen Allied divisions.

But let us not lose sight of the fact that Allied aid to Kolchak was ‘roughly comparable to total Soviet production in 1919.’[xxi]

Semyonov was a pirate king of the railways; Ungern hated the modern world; Kolchak and his officers denounced the international. But none of the warlords of Siberia would have made it very far without the Allies.

Regardless, the Whites had struck a heavy blow on the Eastern Front. The Ural Mountains had been re-conquered for counter-revolution, and the Allies were staking a million rifles on the victory of Admiral Kolchak. By this time, as we will see in the next few posts, the threats to the Soviet Republic on other fronts had multiplied and grown.

***

Go to Revolution Under Siege Archive

[i] Beevor, Antony. Russia: Revolution and Civil War 1917-1921 (p. 111). Orion. Kindle Edition. I made harsh criticisms of this book. But as you can see, I have found a lot of useful material in it.

[ii] Beevor, p. 112

[iii] Beevor, 296

[iv] Smele, The ‘Russian’ Civil Wars, 269 n65, 348 n13

[v] Smith, Russia in Revolution, p 200

[vi] Palmer, The Bloody White Baron,92

[vii] Palmer, p 104-106

[viii] Beevor, p. 331

[ix] Beevor, p 295

[x] Wollenberg, The Red Army, https://www.marxists.org/history/ussr/government/red-army/1937/wollenberg-red-army/ch02.htm

[xi] Dauria is also another name for the Transbaikal region

[xii][xii][xii] In spite of his hatred of Chinese and women, Ungern during this period spent 7 months in China and married the daughter of a Chinese general. Palmer guesses that this was a political marriage setup by Semyonov. Palmer, p 111

[xiii] Palmer, 93

[xiv] Mawdsley, The Russian Civil War, p 200-201

[xv] Beevor, p. 250

[xvi] Palmer, 113

[xvii] Rayfield, in Stalin’s Hangmen

[xviii] Mawdsley, 183

[xix] Mawdsley, p 202

[xx] These numbers are tallied from information provided by Mawdsley, p 198

[xxi] Mawdsley, 198