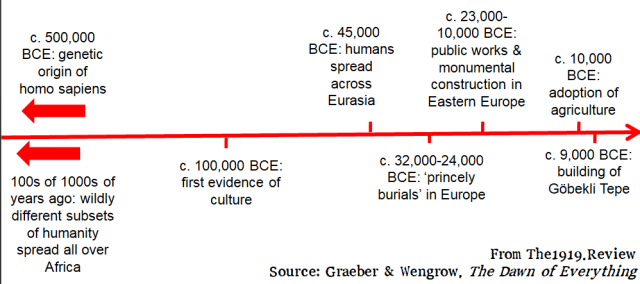

Hi folks, this post represents me putting a rough-and-ready finish on a job I left half-done a while back. You’re reading a long-delayed conclusion to my series Before the Fall: Notes on The Dawn of Everything. I have now finally finished Graeber & Wengrow’s fascinating book and can offer my thoughts on the back half of it.

I had far fewer problems with the book as a whole than I had with the first few chapters. Experts who have criticised this book have generally thrown in a few nice comments as well, and it’s easy to see why. The Dawn of Everything, as the name suggests, is sweeping. I feel a wide range of people will find things in it that they really like even if they can identify places where they think the evidence is thin or where the reasoning invites a ‘well… not necessarily.’

It’s often argued that inequality and power structures are necessary in any sufficiently large population; once you go past a few hundred people, the argument goes, you need governments, ruling classes and bureaucracies. Graeber & Wengrow disagree, and this is the strongest point in the back half of the book. It’s demonstrated most clearly in their survey of early cities around the world (such as Teotihuacán and Mohenjo-Daro) that had egalitarian features. Outside cities, it’s also obvious in the clan structures of indigenous North America, imagined communities as big as a city that linked disparate strangers across vast distances.

I agree with the authors on this point around scale and have for a long time, and it was satisfying to read their arguments and examples. I can exercise power through my membership in unions, campaign groups, political parties, and through my vote. The late David Graeber would scoff at how limited these powers are, but the point is that these are powers I exercise precisely as part of a large collective, not as an individual or in a small group (and better versions of my union and my democracy can be pointed to or imagined). People can be powerless in a small, intimate group – an abusive family, a house share under a controlling landlord, or a tyrannical workplace – and powerful in larger collectives of the kind I just mentioned. In fact larger workplaces tend to have more power than smaller ones. It’s a bit like blaming environmental devastation on ‘too many people’ – what really decides the question is how the people are organised, not how many there are.

Another idea that comes under fire is what I call tech-tree thinking. This assumption is there in the architecture of videogames but a lot of writers also assume that societies ‘develop’ or ‘achieve’ certain upgrades like agriculture or democracy, which provide a buff to their stats, while some other societies ‘fail’ to do so. Humans dabbled in agriculture without committing to a full-on farming life for many thousands of years. Some took on farming then gave it up when it didn’t work out for them. Some never bothered with it. And we find examples of democratic institutions throughout the archaeological, anthropological and historical record. These are not thresholds that peoples pass through or fail to pass through. They are things we can choose to do or not to do.

Here’s a point that never would have occurred to me, but that I found compelling: Graeber & Wengrow see (at least some) early cities as cradles of democracy, and trace the origin of aristocracy to the ‘heroic societies’ of nomadic pastoralists. In the picture they paint, democracies are developing in cities, aristocracies in the hills nearby. They trade with each other, but develop in mutual opposition. Later the aristocratic nomads conquer the cities, but for long periods after that royal power is circumscribed by powerful urban councils.

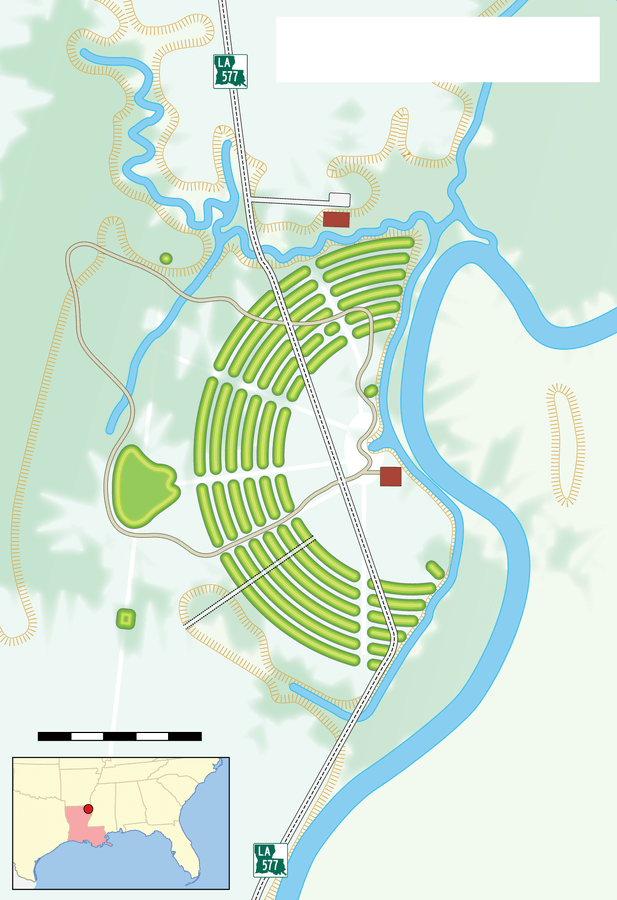

The most interesting story unfortunately also struck me as the most tenuous in terms of evidence. The authors paint a picture of a powerful kingdom developing along the Ohio river in North America, imposing the will of its rulers through mass bloodshed; of this society collapsing as the population migrated to freer places; of a cultural memory of this experiment in hierarchy and empire digging itself deep into the traditions and instincts of the North American Indians, even vast distances away; of this memory informing the development of an anti-authoritarian political tradition. It’s a great story because it shows indigenous political institutions as something other than ancient traditions; they were informed by a particular experience in the not-too-distant past. It’s compelling and could well be true, but the evidence related here doesn’t prove it. It’s an example of how your mileage may vary with some of the material in this book. Speaking of material, they sometimes advance explanations for things that I can only see as second- or third-order explanations. We hear that large scale adoption of certain crops depended on that particular crop arbitrarily being used for (that most convenient of phrases) ritual purposes.

I still see a lot of value in categorising different societies using the rubric of production, in seeing economics as something that sets broad but hard limits on what can happen in politics and culture. While I don’t think the authors share these ideas, they didn’t go out of their way to attack them either, though I expected them to. The promised ‘plague on both your houses’ did not descend; Hobbes came out a lot worse than Rousseau.

I’ve had this book for at least three years, I shit you not. I wanted to read it very carefully and take loads of notes, so what I was doing with my little series here, 14 or 15 months ago (Jesus Christ), was reading, note-taking and writing a blog post on each chapter. This project, modest as it was, ground to a halt after just five chapters out of twelve, and so did my reading of The Dawn of Everything. My interest in the book had somehow become an obstacle to my actually getting it read. I made zero progress for a long time, then bit the bullet, bought the audiobook, and got the rest all listened to in a couple of weeks. No note-taking and no twelve-part blog series, just this capstone on the job I left unfinished.