Last month OpenAI boss Sam Altman announced that his company had created an AI tool that could write a short story. You know the most depressing thing about this news? Sam Altman did not wake up one morning and, just on a whim, ask his software to write a story. His company worked really hard to get it to write a short story. No doubt some tech worker missed a kid’s birthday, maybe even birth, in order to work long hours on it. They plagiarized and polluted for it. Getting an AI that could write a short story was something they had to pursue.

Here’s the thing: even if it was easy and cheap and green, why would anyone want a machine that can write a short story? Is there a shortage of people who can write stories? Is writing stories a chore, like washing clothes or cutting grass? Are people crying out for relief from the burden of being creative?

I made it clear enough last week that I think this Gen AI thing does have limited uses (“a moderate productivity booster in certain situations”, as my commenter, The Director from MilitaryRealism.blog summed it up). I’m not qualified in any very technical fields like engineering, logistics or programming, but I’ll add that I can see potential uses that could be important.

Writing is more my area; I have an English degree and I’ve worked in teaching and libraries. So I don’t hesitate to say that short fiction is a glaring example of something that’s not a useful application of Gen AI by any measure.

Full disclosure, I haven’t read the AI-written short story. I read a lot, but I don’t happen to have a Gen-AI-short-story-shaped gap in my reading.

It’s not inevitable

The Guardian got some writers to react to the short story written by the machine. Most of the reactions ranged between ‘Wow, this is actually pretty good’ and ‘I fear for my livelihood.’ Kamila Shamsie pointed out that GenAI will reproduce and reinforce all the biases, all the racism and sexism etc, in its ‘training materials.’ For Nick Harkaway, the story is an ‘elegant emptiness’ and being moved by it is like a bird falling in love with its reflection in a window. He emphasises that ‘none of this will just happen. These are policy choices, and the end result will be the result of a conscious decision.’

That’s what the hype-mongers want us to forget, isn’t it?

The future promised by Gen AI is one where nobody is paid to do anything creative or educational; instead, computer programmes owned and controlled by a few billionaires create flat, uncanny versions of what humans used to create. For some reason we are all supposed to be excited about this. But whether you feel excitement or dread, either way you are making the mistake of treating the whole thing as inevitable and natural.

Actually, there are humans making decisions and investments at every link in the chain here. And some, like CD Projekt Red, are making decisions unfavourable to the spread of AI in creative industries.

I don’t think AI is going to put writers out of a job. The vast majority of us are already out of a job. Tech bros claiming to have made a programme that can do what we do, and expecting us to be pleased about it, is just the latest in a long line of insults, and far from the worst.

I say ‘far from the worst’ because I don’t think these AI tools are about to revolutionise the publishing industry, any more than they have revolutionised any of the other things they were supposed to revolutionise. It will mess with a lot of people’s livelihoods and it will muddy things up for a while. But it will not be a game-changer. The wave may leave behind puddles but it will recede. So I don’t believe the tech bros’ dystopia will happen.

GenAI will probably carve out and retain certain niches, for better or for worse, in the publishing industry. But a machine can’t actually write a story. There’s a few basic category errors at work here.

Why can’t a machine write a story?

First, the ‘AI’ that exists today is not some sentient machine-mind (‘alternative intelligence,’ in the disappointing words of Jeanette Winterson). Maybe some day we will have that, and our android cousins will write their cyber-Iliads, which will be very cool. I’ll be the first in line. But that’s a whole different thing. I saw someone in a comment section gushing that ‘we have taught sand to dream.’ But what we have now is just glorified predictive text. Whether in written or visual or musical form, it just shows you the lowest common denominator of what’s already out there in the culture.

Second, writing is about expressing your feelings and communicating your thoughts and experiences. A computer doesn’t have these things. It can imitate the way humans express them, provided a bunch of rich people decide to devote stupendous sums of wealth to making it do so. But again it’s not the same thing.

What if the computer’s imitation gets so good we can’t tell the difference? And aren’t some human writers also basically hacks, unoriginal, etc?

First, every writer does not have to be Arundhati Roy for the point to stand that a computer can’t be Arundhati Roy. Stories are rooted in material reality and our experiences of it. No training materials or prompts can produce something like The God of Small Things, which is viscerally a story of its time and place.

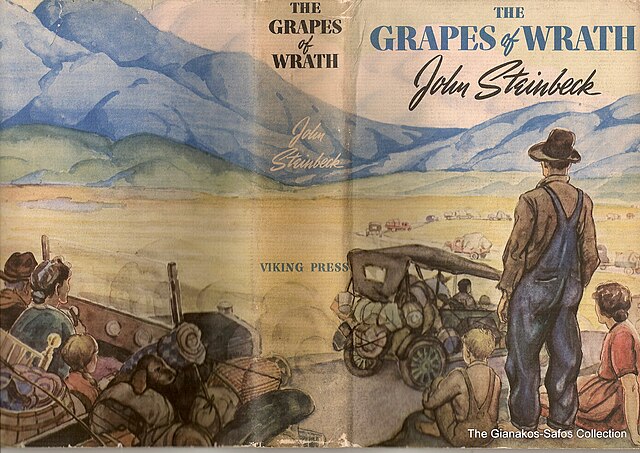

Or imagine if The Grapes of Wrath had been written using pre-existing ‘training materials.’ It would have portrayed the Dust Bowl refugees as incendiary vagrant criminals and the cops as brave defenders of civilisation.

Even if the imitation seems to be perfect and seamless, the above points will tell. Stories are not pure exercises in form. They are about things. The most important ones are about things nobody has written about before. Even science fiction and fantasy stories are about themes and feelings that really exist.

AI in Gaming

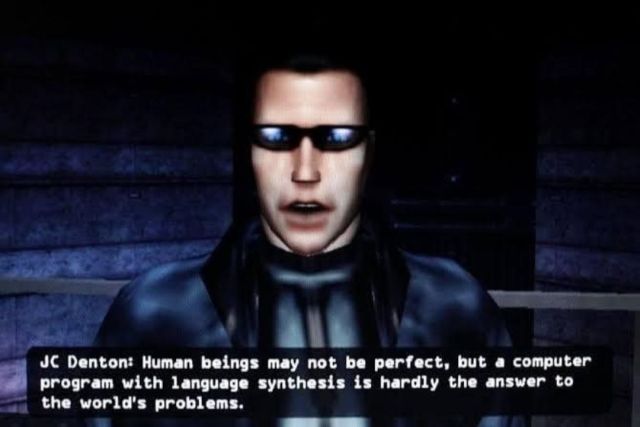

I first became familiar with the phrase ‘Artificial Intelligence’ in relation to games. AI is what tells the mercenaries in Far Cry to search the jungle for you systematically when you hide. It’s what tells the hostile army in a Total War game to oppose your cavalry with spears. AI is what’s breaking down when your little villager takes a shortcut past ten enemy catapults, or when a Nazi stands out in the middle of a Norman field waiting for you to shoot him.

You’d think GenAI would have massive applications in gaming. But so far it’s been a real damp squib in that sector.

Recently PCGamer reported on a wild example. Basically, Microsoft made a demo based on a game called Quake 2 using Gen AI. The project used three megawatts of energy – the output of tens of thousands of solar panels. All that, for what? An incoherent, uncanny experience that looked vaguely like Quake 2 and that gave players motion sickness. For context, Quake 2 (that is, a version of Quake 2 that is the full game and that actually works and doesn’t make you nauseous) was made over 25 years ago by a team of just 13 people.

Something to think about: if they had managed to remake a part of the game exactly as it was with AI, that would have been hailed as a triumph. But… Then we’d just have a game level that already exists.

How do I explain this for people unfamiliar with games?

Imagine if I rewrote one chapter of Killing Floor by Lee Child, and presented it here on The 1919 Review expecting your adulation. But in my rewrite, the names of the characters change every other paragraph, and the font somehow gives the reader a headache. I rewrote it by listing every time a particular word is used then arranging the words according to arcane predictive rules. And, somehow, it took the entire output of a nuclear plant just to power the special laptop I used to do this.

That’s the essence of the Quake 2 situation, as best I can explain it using books as a comparison, but to be fair (and as I’ve made clear above), GenAI has actually produced more polished results when it’s confined to text.

In both cases the same questions arise: what is the purpose of this? How can the results (good or bad or just trifling) possibly justify the expense and the effort and the pollution? Why are we all expected to indulge Big Tech even when the project into which they are pouring so much wealth is largely unnecessary where it is not actually harmful?

GenAI is in many ways like crypto: the tech bros have invented a new toy and they demand that everyone takes their toy seriously. They demand that we sacrifice the future of the planet in order to sustain their toy. This toy is at the heart of an investor frenzy. They promise that when their toy has taken over the world, it will right all the wrongs it has done along the way (crypto, we were told, will actually save energy by putting all the banks out of business, thus reducing their emissions to zero; in the same way, we are told that AI will actually come up with clever ways to save energy.)

In other ways GenAI is not like crypto. It actually has utility, even if you agree with me that this utility cannot on balance be justified. It can be a lot of fun. It can make it easier to write emails. Its potential in technical fields is an open question.

But it has no utility in writing stories or developing videogames. It’s actually difficult to wrap your head around how stupidly wasteful and contrived such projects are. Even if that wasn’t the case, and even if the results were decent, it’s not worth one single artist losing their livelihood.