The new Dune is phenomenal. Two-plus years ago Dune: Part One got me out to the cinema for the first time since Covid and it was exhilerating. Part Two is reported to be even better. But Frank Herbert’s 1965 novel Dune has been adapted for the screen before, more than once. I have seen all these adaptations, because I have a strange fascination with Dune which is part nostalgia because I first read it aged 14, part a mature realisation that the things we enjoy don’t have to coincide with the things we believe in, and part, no doubt, reasons that could be best explained by Freud (sandworms), Marx (family retainers) and Edward Said (white saviour complex).

Enough deprecation. I also like this story because it’s exciting, intelligent and haunting. The author takes politics, economics and ecology seriously while telling a great story. How well has that translated to the screen?

This review will take a look at David Lynch’s 1984 movie, the Sci Fi Channel’s 2000 miniseries, and Denis Villeneuve’s 2021 adaptation of the first half of the novel.

Villeneuve is talking about adapting the Dune sequels. In a bit of a sequel to this post, we will look at the 2003 adaptation of Dune Messiah and Children of Dune.

Harkonnen Horror Picture Show

God created 1984’s Dune to train the faithful. For every good thing I can say about it, there’s a bad thing too, and vice versa.

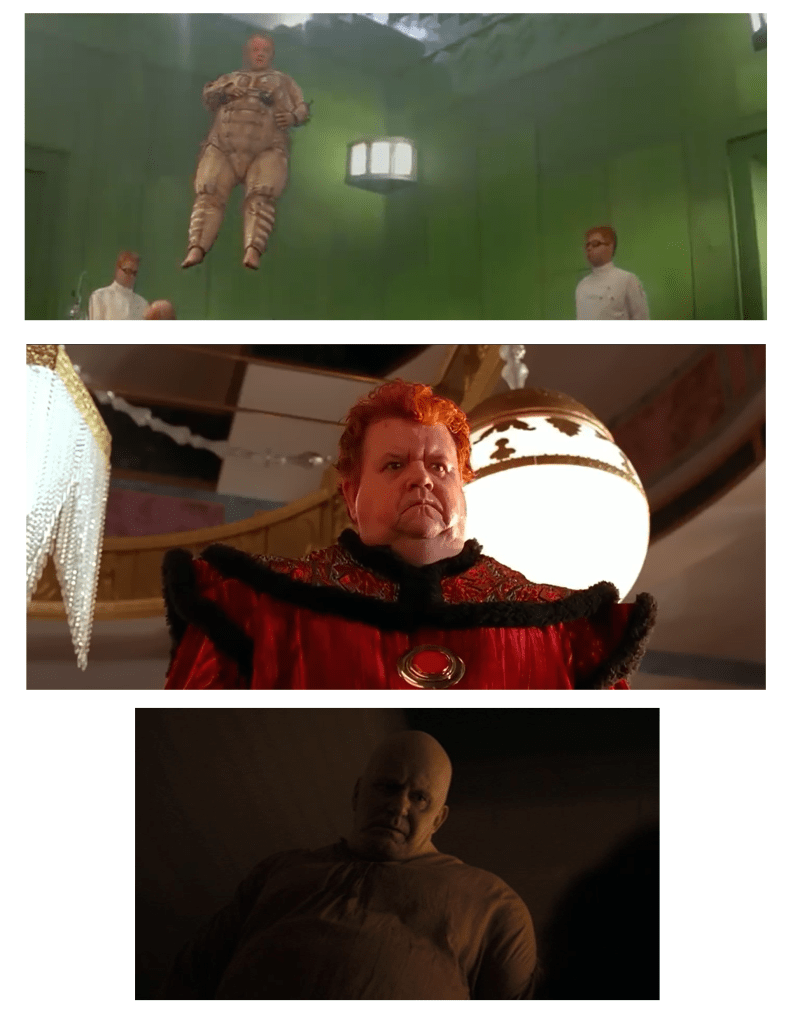

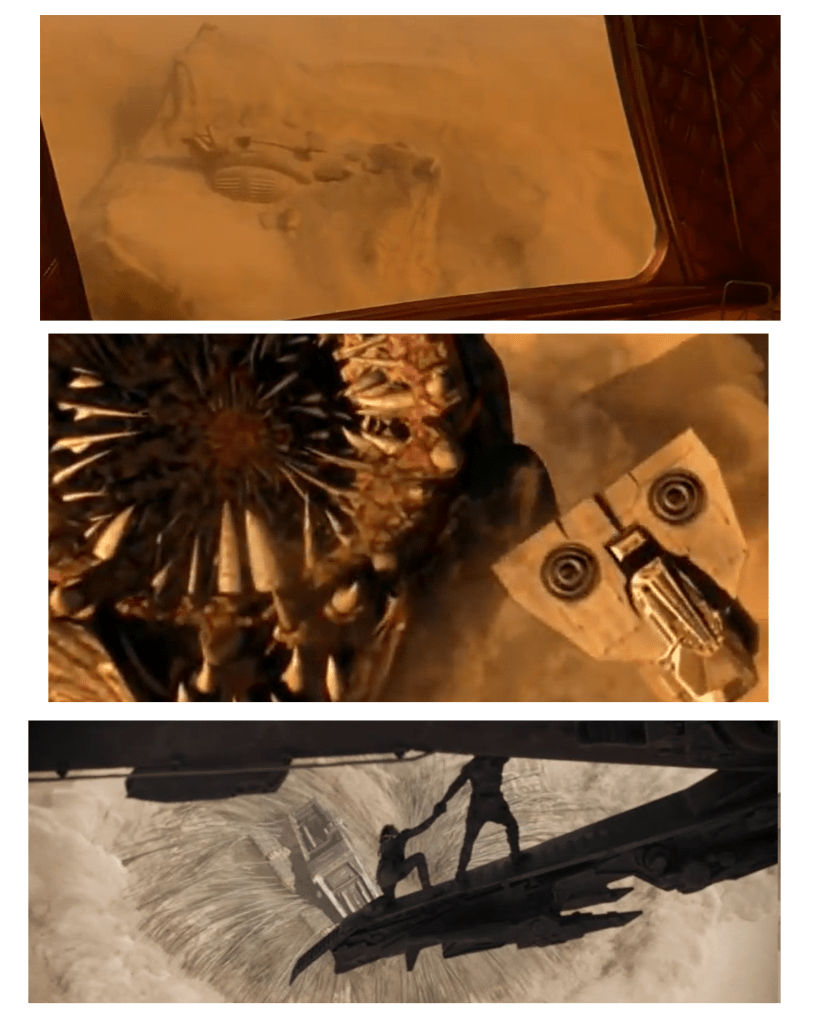

To begin with, something bothers me about the interiors. The Atreides live in surroundings of Victorian frumpiness, gaudy but flat, like the decor in Boris Johnson’s house; the Harkonnens in a green-lit space slaughterhouse. For all the implicit homophobia in the way the Baron is portrayed, something about the campiness of the whole set-up makes me think the whole evil cabal might jump out of their chairs and start singing ‘Time Warp’ at any moment. But other elements of the visual design are brilliant – the guild spice navigator and his cohorts, who prefigure the fascinating visual excess of Warhammer 40,000; the tonsured Bene Gesserit; the faceless rubber menace of the Harkonnen troops.

The spaceships look cool; but the visual sequence in which the guild navigator bends time is slow, unclear and not necessary.

I like the weirding modules. These are invented out of whole cloth for the movie: in short the Atreides have a special weapon that can kill with the utterance of a sharp syllable. This idea fits pretty well in the world of Dune and helps the story along. For example, it explains what’s so special about Paul from the point of view of the Fremen: he brings a powerful new weapon to the table. But the shields, personal force-fields used by combatants in the universe of Dune, look silly.

The movie is rushed and incoherent. It might have gotten away with telling such a huge story in just over two hours, but it goes out of its way to be confusing and to trip us up on irrelevant things. It’s difficult to imagine anyone who hasn’t read the books being able to follow what’s going on. But the final half-hour strides along with a formidable momentum and plenty of cool imagery.

At the very end of the movie it suddenly rains on Arrakis – a development that makes no sense in the logic of the world, but which is absolute magic on a simple storytelling and thematic level. I can see why they couldn’t resist.

It’s a movie I could talk about, back and forth, is it good or is it bad, for a long time.

A very delicate time

The opening of 1984 Dune is problematic in ways that are thrown into sharp relief by the quality of the 2021 Dune’s opening. In 1984 Dune, we begin with Princess Irulan, a very formal narrator who stares straight into the camera and explains things, followed by a scene in the imperial throne room. In 2021 Dune we begin with Chani narrating over a striking visual sequence.

The 2021 approach is more democratic and materialist, centring the indigenous Fremen and the key resource they control rather than the galactic aristocracy. But it is also much better from a storytelling point of view: it is rooted in real and tangible things, while narrators and the high politics of throne rooms are distant and abstract. Chani is narrating but also participating in a sequence that conveys visually the importance of the spice, the oppression of the Fremen by the Harkonnen, and the transfer of power from the Harkonnens to another noble house.

The guild spice navigator in the 1984 Dune is a top-tier movie monster. In the books we don’t see him until Dune Messiah, but here he makes his grand entrance in the opening sequence. Unfortunately that is a big problem. Although he is cool, he is one of several big things that we don’t need to know about this universe right away, or at all. But the movie goes out of its way to foreground him.

Comedians of Dune

The Harkonnen scenes in the 1984 Dune leave me with a vague impression of grotesque-looking people bellowing and jabbering monstrous things at one another, punctuated with maniacal cackling. The 2021 Dune is a bit humourless by comparison. There is an early moment in which Paul and Duncan Idaho share a chuckle. But that is an oasis in a desert of dourness.

There is, to be fair, one other joke in the movie:

‘Smile, Gurney,’ says Duke Leto.

Scowling, Gurney replies: ‘I am smiling.’

Someone has decided to make Gurney ‘the grumpy one.’ It’s a good joke, delivered well by the actors. Is the movie taking a dig at its own serious tone? Or is it opening itself up to the retort: ‘Which grumpy one?’

Still, the 2021 Dune is better in almost every way. The storytelling and worldbuilding are far more skilful, conscious, economical; the screenwriters treat words as the Fremen treat water. The visuals play with light and shade, convey weight, grit, thirst, scale. It does not lack that essential quality: weirdness, accident, quirkiness (Who thought of giving the Atreides bagpipes? Give them a medal) but it doesn’t allow that element, either, to get in the way of the story.

In any adaptation, fidelity to the original is not crucial for me. Things have to change in the move from one medium to another. A change for the better, or a change necessary for the medium, justifies itself. But for what it’s worth, the 2021 Dune is much more faithful to the original. Both other adaptations resort to arming their extras with projectile firearms. But in the book and the 2021 version, shields have rendered firearms obsolete, and combat is primarily a hand-to-hand affair.

Budgets of Dune

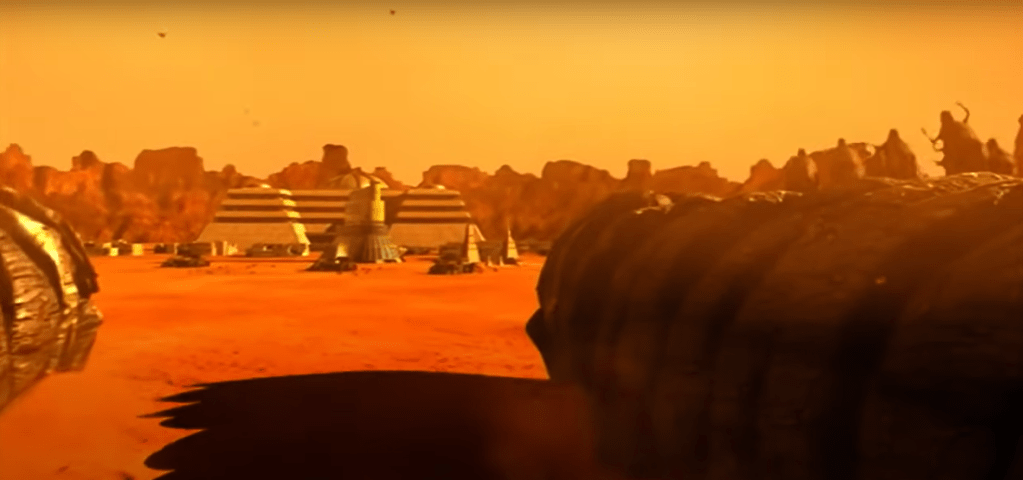

An even smaller point against the 2021 Dune is its portrayal of the city of Arrakeen. In a movie that cost $165 million to make, this key location appears to be nothing more than a scale model, entirely devoid of human life. The 2000 TV adaptation, working with a budget of $20 million, manages to convey a lively and bustling place. (In case you’re wondering, the 1984 Dune cost about $40 million.)

Now we come to the most obscure adaptation, Frank Herbert’s Dune, a three-part miniseries for the Sci Fi Channel written and directed by John Harrison.

(It was one of three very fine miniseries released by the Sci Fi Channel around that time, along with Steven Spielberg’s UFO epic Taken and Battlestar Galactica. The latter ended up running to the proverbial six seasons. It was an underappreciated moment in the history of ‘prestige TV’.)

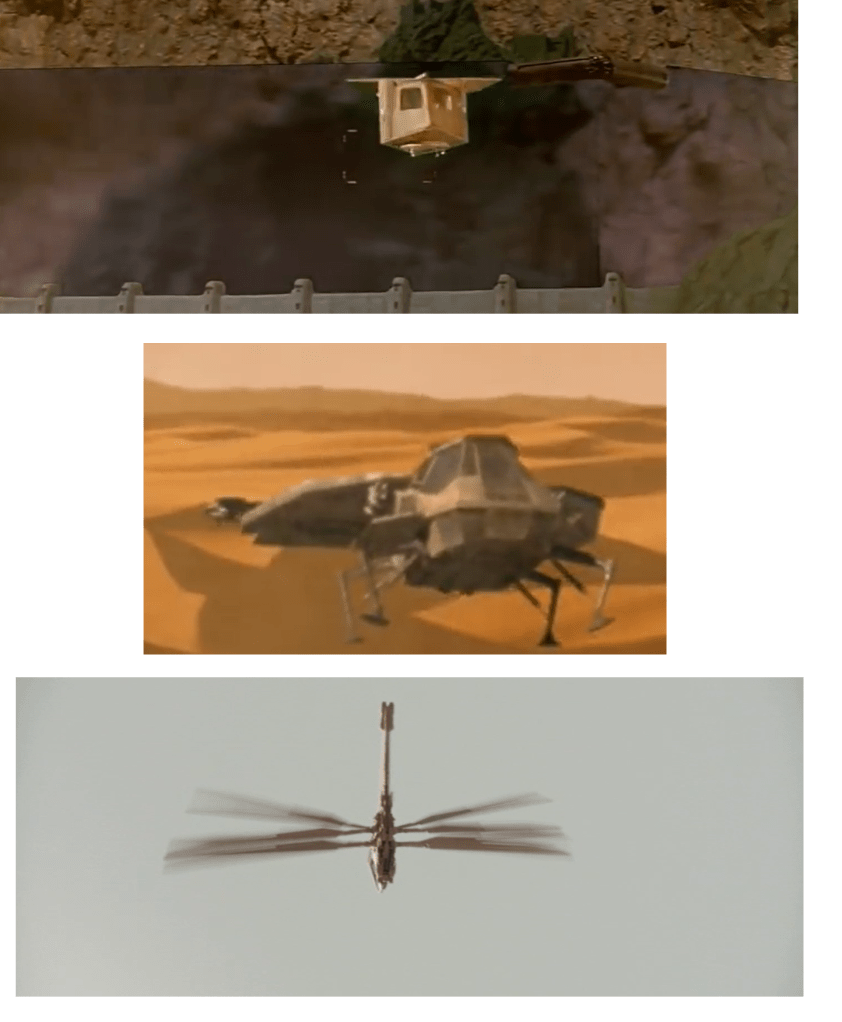

I’ll level with you up front: Frank Herbert’s Dune is not visually spectacular – the CGI is dated and some of the costumes look tacky.

But the actors are impressive. It is long not because it is bloated, but because it has made a conscious decision to tell the story more fully and faithfully, without unseemly haste. Everything about this adaptation is confident and assured, as if having a smaller budget gave it much more freedom.

And about that CGI: on a technical level, it would not pass muster today. (Though nostalgia or irony might induce people to deliberately copy this style in the future – stranger things have happened). The images are well-composed and are shot and edited in such a way that, interspersed with live-action footage, they tell a compelling and comprehensible story. A lot of today’s filmmakers could learn a lot from how the CGI is used here, how John Harrison does so much with relatively little. The result is that a CGI-heavy action scene, such as when the spice factory is eaten by a worm, is a genuinely tense experience.

In a fantastic scene, the ‘Beast Rabban’ gets a personal comeuppance he never gets in the novel when he is killed by a mob in the streets of Arrakeen. I guess budget dictates that some additional scenes must happen in this set, to justify the expense of building it; but budgetary needs can coincide with storytelling needs. It is satisfying to see this showdown happen in this familiar place. In the novel, by contrast, we are told in the most perfunctory Shakespearian way that ‘Rabban, too, is dead’ – offscreen somewhere.

I don’t want to over-praise something that, after all, will have dated poorly, especially measured against the new big-budget spectacle. But here’s one last piece of praise: Frank Herbert’s Dune is the only adaptation to leave in the crucial banquet scene (into which it inserts the Princess Irulan and a bodyguard of Sardaukar. It’s important later that we know who these people are, so it makes sense to feature them here).

It was shot in Czechia, and you can decide for yourself whether that (a) results in lamentable whitewashing of the Middle Eastern elements or (b) to your great relief, distances the adaptation from the wild orientalism of the novel.

Recommendations of Dune

If you want a spectacular modern science fiction epic, well-conceived and well-executed, with current stars and big budget, you should watch the Denis Villeneuve Dune.

If, like me, you are really into Dune and also interested in the process of storytelling and adaptation, these versions are all deeply intriguing.

If, like me, you are interested in things that are good but also kind of bad, you should watch David Lynch’s Dune. The highs and lows are equally bold and striking.

If you liked the 2021 Dune and want to know more, but aren’t much of a reader or can’t get into the books, the 2000 miniseries is a good place to go to delve deeper into the story. It would be a good option for someone who prefers the pacing and serial form of TV shows. It also has the great advantage that it has a direct sequel to introduce you to the later books in the series.

Next week I’ll talk about that sequel: the novels Dune Messiah and Children of Dune, along with the TV miniseries Frank Herbert’s Children of Dune (2003). Stay tuned for that if you want to hear about how a low-budget TV adaptation can be better than the source material. Until then, enjoy Dune: Part Two.