Spoilers below.

What makes Squid Game different from Hunger Games and Battle Royale? The fight to the death in Squid Game is not just bigger and bloodier. It is voluntary. Stephen King’s Running Man also features a lethal game whose contestants are volunteers. But King’s novel, and its movie version, and Hunger Games and Battle Royale, are set in future dystopias. Squid Game is set in our world, right now.

The conditions in North Korea are so desperate that Sae-byeok risks death to escape. But when she enters the game she risks death again, this time to escape from the desperate conditions for the poor and working class in South Korea, to escape from capitalism. As someone says in Episode 2, it’s worse out there than it is in here.

The final episode of Squid Game hammers home an anti-capitalist argument that has been running through the whole story. Many have commented on this, including the writer and director Hwang Dong-hyuk. This article goes into some detail. But I want to focus on the voluntary nature of the games and how this plays into the anti-capitalist message.

In-ho’s words in the last episode make this point very clear. He says words to the effect that ‘You chose this,’ ‘You signed up for this,’ ‘Nobody forced you.’ Another villain, the psychopathic Sang-woo, insists on Gi-hun’s personal responsibility for all the killing.

Within formal logic, In-ho’s argument is unanswerable. But Gi-hun recoils against his words and against Sang-woo’s. They are wrong. Gi-hun knows it in his gut, and so do we.

It’s true that the game is voluntary. In-ho himself, undercover among the contestants, casts the deciding vote for them all to leave. But for some reason, we don’t accept their arguments.

‘You chose this,’ ‘You signed up for this,’ ‘Nobody forced you.’ That’s what we hear when we complain about our jobs, our mortgages, our car payments. We even hear a version of this in the cliché that ‘people get the government they deserve’ – ie, the people are responsible when their elected leaders betray them. In the most formal sense, it’s all true.

The game’s overseer keeps insisting on ‘equality’ as the fundamental principle of the whole operation. In theory, capitalism is fair and we’re all equal. In theory, the worker and the boss meet one another ‘in the marketplace’ (wherever that is) on a basis of complete equality. They agree to a contract which is satisfactory to both: I work for you, and you pay me. The law says these two people are completely equal. The law says this contract is voluntary.

But the reality is very different from the theory, and from what the law says. That reality is illustrated in every episode of Squid Game.

When we first see Gi-hun, we are invited to see him as a waster and a messer. Then in mid-series we hear about the auto workers’ strike Gi-hun was involved in ten years ago and about the lethal police violence. This sacking was a catastrophe from which his life has never recovered. He got into debt with failed business ventures (Isn’t that what you’re supposed to do? Isn’t that what they tell us to do? Be an entrepreneur?). His family has broken down. No wonder he’s in the situation he’s in. It could happen to you or me.

Another contestant has decades of experience as a glassmaker. We can assume he’s got a similar story to tell. And we see with our own eyes how Ali was scammed by his boss.

The final episode hammers home the point. A TV or radio playing in the background of a scene reminds us about the crisis in household debt. Early on in the series, we might think, ‘OK, these contestants are people in extreme situations – gambling addicts, refugees, gangsters.’ But the final episode insists: this situation is general.

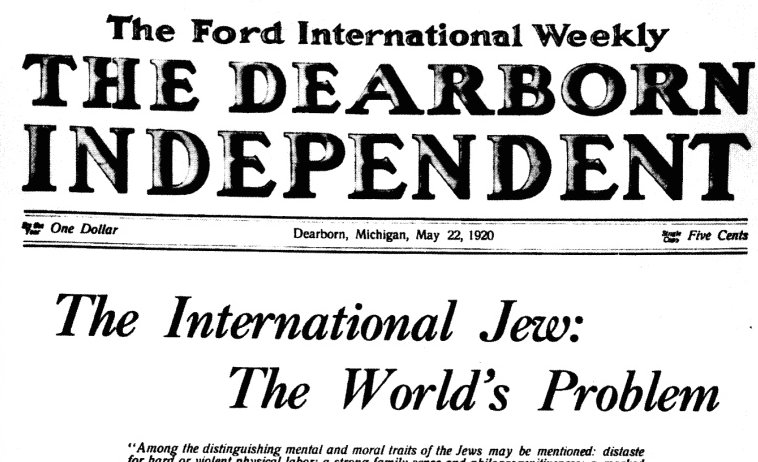

For all its brutality, Squid Game is written with compassion and humanity. These games are not a public spectacle or a reality TV show. They are secret. The public at large do not enjoy the games. They would be sickened if they knew the games were happening. The audience, lapping up other people’s suffering for entertainment, are the handful of billionaires who bankroll the whole operation – and who got rich making everyone’s lives so desperate and precarious in the first place. The indebted and desperate Gi-hun lives on a different planet from these ‘VIPs.’ To claim they are equal is a vicious lie designed to keep Gi-hun in his place – and, perhaps, to soothe the consciences of the wealthy.

People are drawing parallels with Money Heist, another series on Netflix. Like Squid Game, it has won a colossal audience in spite of the fact that it’s not in English. This Spanish crime series is knee-deep in socialism. A miner from Asturias who calls himself ‘Moscow’ sings ‘Bella Ciao,’ talks about the 15M movement and supports his trans comrade; in a fierce battle in the ruins of the national Bank of Spain, the robbers denounce the forces of the state as fascists and draw inspiration from the Battle of Stalingrad. But what’s more important than any of these Easter eggs is what this guy said: that what makes Money Heist popular is the class rage it channels.

Money Heist and Squid Game tap into our despair and anger at the brutal and unfair system we live under. Hundreds of people being gunned down in a scene that’s part Red Light, Green Light and part Amritsar Massacre – that’s not a fantasy. That’s what it feels like to live in this society. If a story can tap into such a feeling, language is not a barrier. We live under the same system and even if we speak different languages we can relate to common problems and struggles.

We live in a time of mass protest movements against the wealthy and the state on every continent (Colombia, Sudan, Lebanon, Myanmar, and the list goes on and on). It would be strange if this mood was not reflected in some way in popular culture. But it’s a sign of the times that the entertainment industry – and maybe to an extent audiences – are not ready for a story that is simply about class struggle (with surprising exceptions like Superstore). Politics is a dirty word. It has to be smuggled in, disguised in more wholesome and palatable fare, such as a story about the origin of a mass murderer, about a bank robbery, or about a game show in which four hundred people die horrible deaths. In cynical times, the earnest and compassionate stories we secretly crave can only be packaged in the trappings of cynical and pessimistic genres.

*

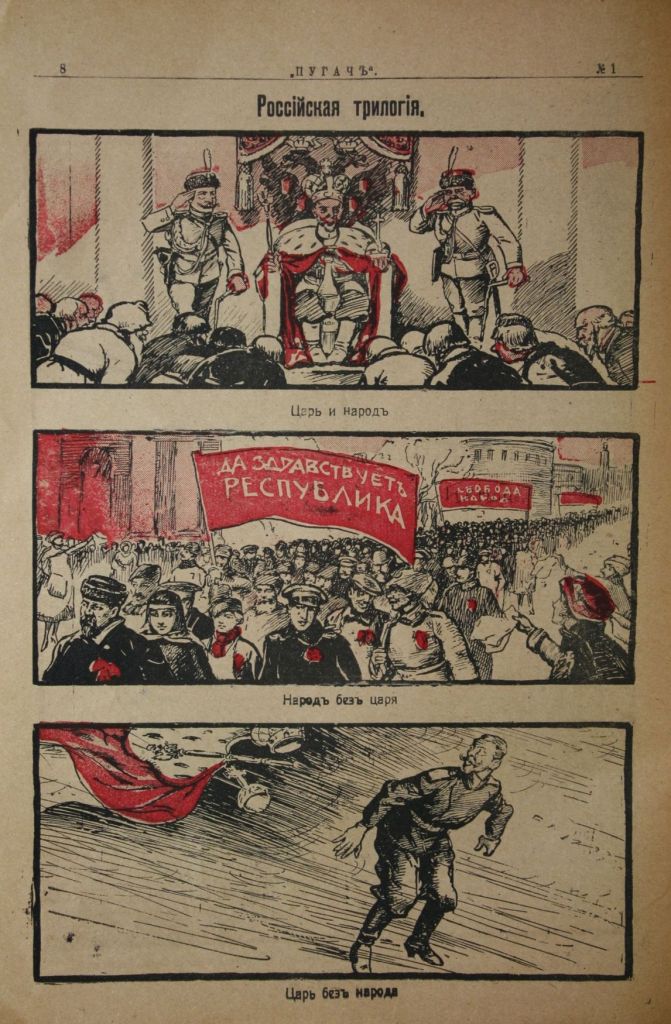

Thanks to all my readers. This week I took a break from Battle for Red October, my ongoing series about the Russian Civil War. The series resumes next week. If you like what you read here, leave your address in the box below and get an update whenever I post.