While working on my ongoing series Revolution Under Siege, I was happy to come across a great primary source: the 1919 diary of the White Russian General Alexei Pavlovich Budberg.[i] I found it not only informative, but compelling and even moving. It should be released as a Penguin Modern Classic, or Vintage, or Oxford, or one of those. It’s literature.

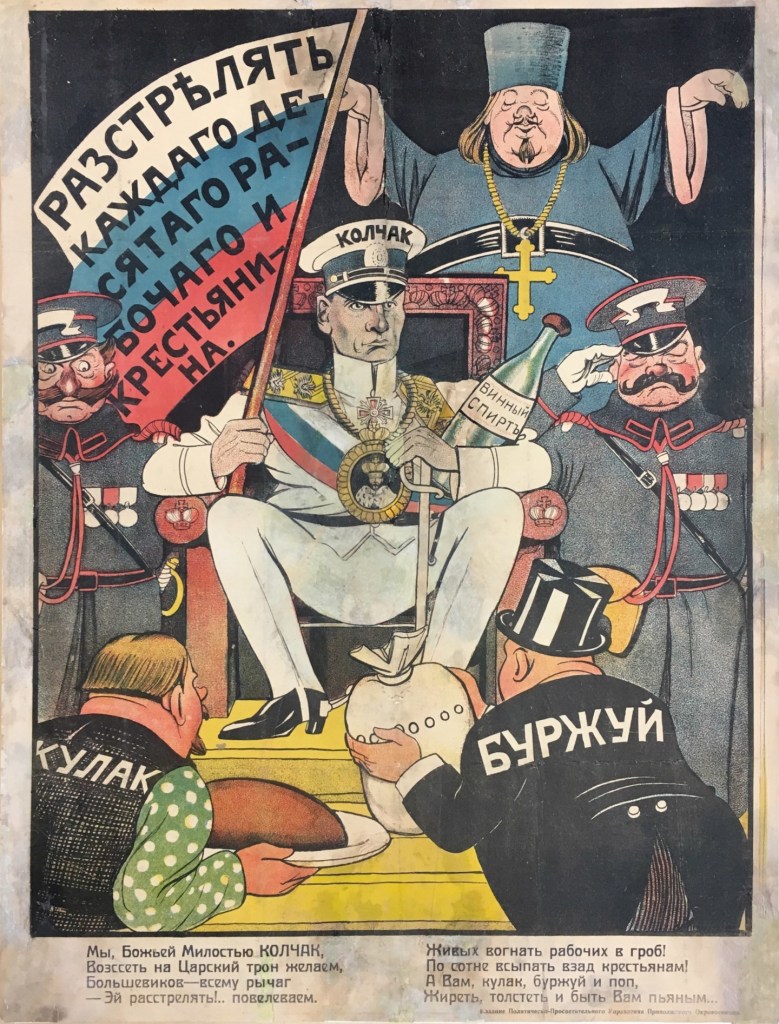

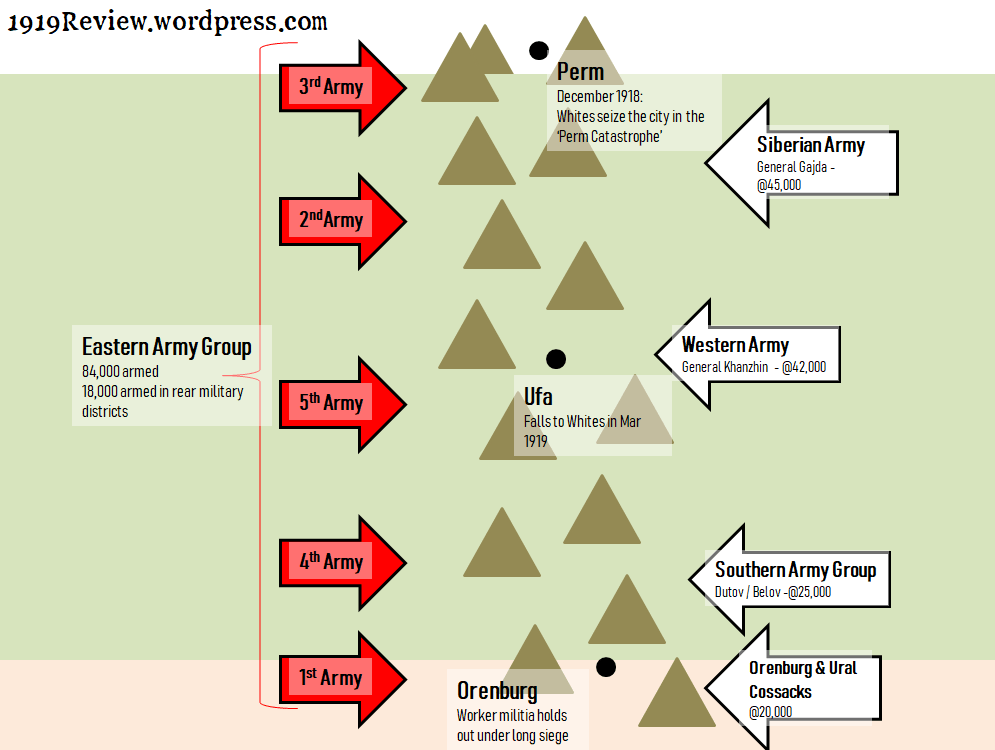

Budberg was a middle-aged officer of the old army who served the Siberian White regime of Admiral Kolchak as War Minister during 1919.

The diaries he kept during that time are full of sharp ironies and deep conflicts. Budberg is fighting for a bourgeois Russia but he loathes the bourgeoisie and thinks little of his fellow Russians. He hates the Reds viscerally, but he continually voices his grudging professional respect (‘How I envy the Reds now! No matter how vile they are, decisive people are at the head of their army’). He is annoyed at Allied demands and importunacy – but without them, he would have no rifles or boots for his men. He is in favour of a more centralised and out-and-out dictatorship – but it is clear to the reader that the White regime is organically composed of vested interests which will not tolerate such discipline, and indeed our narrator is outraged when his friend is arrested for corruption.

The reader respects Budberg, because he is so frequently correct in his dire predictions. At one stage Budberg hears his colleagues boast of how they rejected Finnish offers of an alliance against the Reds. They are proud that they refused to consider any territorial concessions, even in exchange for an alliance which might well deliver St Petersburg into White hands. Budberg says loudly: ‘What horror and what idiocy,’ which occasions looks of astonishment from those around him. But history has vindicated what he said.

At the same time I found him far from sympathetic. His contempt for Russians comes across in an anecdote he relates:

all the efforts of the railway militiamen to remove from the rails the crowd of peasants and passengers sitting on them were unsuccessful; but when three Czechs appeared and, shouting “let’s go,” began to beat the Russian citizens with butts, the platform and the rails were empty, and the “masters of the Russian land” decorously lined up behind the line assigned to them by the Czechs.

He comments that ‘the Russian crowd needs a stick… of foreign origin.’ This comes from ‘the habit of being under a Tatar[…] a German, and more recently a Jew.’

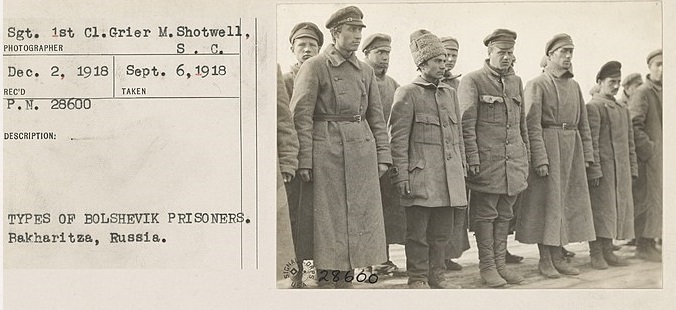

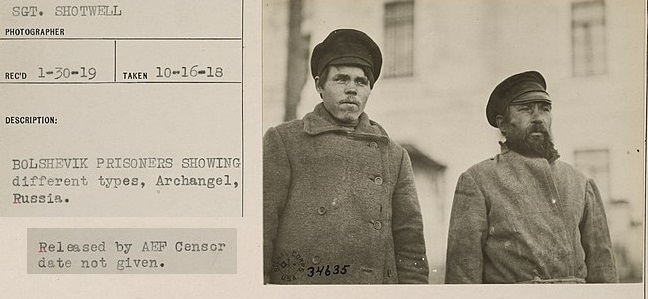

Like most Whites, Budberg believes that the Revolution and Bolshevism are part of a Jewish conspiracy. This belief resulted in the deaths of thousands of Jewish people during the civil war.

His only problem with the coup d’etat by which Kolchak came to power in November 1918 was that it promoted some unqualified people. He has no regrets about suppressing the SRs.

Prophet of Doom

Meanwhile his diary provides valuable evidence as to the weaknesses and crimes of White Siberia. This is all the more impressive because he is not writing in hindsight but in real time.

Budberg is frustrated with critics and talkers – for example, the ladies who draw his attention to problems in the hospitals, but will not volunteer as nurses, or even donate linen. Some concerned citizens demand that schools be built for the children. Budberg puts them on the spot by guaranteeing them money, transport and all the materials they need. But no work is done. His comment is scathing: ‘They are intellectuals, and teachers, and democrats, and accusers, and intercessors, but they are not so stupid as to try to build those buildings that will deprive them of continuing to do nothing.’

Something as simple as providing care to the wounded is hampered by corruption and profiteering and bureaucratic haughtiness. Wounded soldiers arriving late were left all night without blankets, because certain underlings did not want to disturb the sleep of the person responsible for issuing said blankets.

The entry of the Siberian Cossacks into the war is greeted with enthusiasm by all and sundry in Omsk, with Budberg appearing to be the sole exception. Sure enough, he is soon proved right: the Cossacks empty the state warehouses, issue five uniforms to each man; the atamans deliver funds and loot to the villages that voted for them; and when the time comes to fight they are brave but undisciplined. Their attack fails. All they have achieved is to drag the Whites into yet another failed and costly offensive.

A lot of the texture of daily life in White Siberia seems to have revolved around disputes over trains. Usually these were disputes between groups of different nationalities. A whole catalogue of such could be gleaned from Budberg’s bitter writings, but the Czechs are the ones he resents the most. This is another bitter irony, as he is forced into an attitude of grudging respect for the Czech commander Gajda who levels valid criticisms at Kolchak.

There are constant ambitious reforms and overhauls of systems – which will be familiar to workers today in the corporate world or in government departments. The result is a landfill of broken systems, with the real problem never addressed: the lack of qualified people.

He identifies the Reds with senseless and brutal violence. However he is well aware of White Terror and provides insights into its nature: punitive detachments are sent out without training or resources, and quickly resort to indiscriminate violence. Here as in government departments, the key problem in his eyes is lack of qualified people. Everywhere, he comes to realise, military warlords have become used to operating with impunity, and this has gone too far to be contained. These ‘hyenas’ cannot now be tamed. Warlordism, he predicts, ‘will probably eat us, but it itself must perish among the stench it produces.’

Budberg hates General Ivanov-Rinov, who is in his eyes not a military specialist but a mere ‘police bloodhound.’ He relates that Ivanov-Rinov’s wish-list includes kill quotas and the power to shoot all deserters and speculators. We wonder at what point Budberg will realise that the Whites are guilty of everything he accuses the Reds of.

Too far gone

All in all, it is a vivid portrait of a wretched government, of a train-wreck happening in slow motion from the point of view of one qualified to foresee the disaster but powerless to stop it. What he can’t see is that the reforms which he sees as necessary would tear the White movement apart. Challenging speculators, scammers and corrupt people is urgently ‘necessary’ – but he can’t see that the radical measures necessary to fight corruption would send shockwaves through the businesspeople and bureaucrats of Omsk. He is outraged by the warlordism and banditry he sees on his own side – but any real measures to tackle this would alienate necessary allies and even the rank-and-file.

He is more far-seeing than those around him, in a technical sense. He knows not only that a disaster is coming, but how and why it will unfold. We admire him as a protagonist because he knows his stuff and proactively identifies problems and tries his best to solve them. Most of those around him, meanwhile, seem complacent and cynical. In particular those around him greet each new offensive with enthusiasm. He sees that a defensive strategy would be far more effective, and in each case the specifics of his critique are proved right.

But is he really more far-seeing than those around him? The others, whose apparent complacency and amateurism enrage him so much, perhaps see further than him in a political and moral sense. They know their regime is riddled with rot, so badly riddled that it cannot be purged without destroying the whole organism. A defensive strategy makes more sense militarily. But what is there to defend? You are merely buying time for the rot to do its work. It’s too far gone already.

Their panacea: to take Moscow. If they can pull off this goal, they will have problems and resources on a different order of magnitude entirely, and the infantile disorders of the early Siberian days will be a thing of the past. All this explains why those around Budberg are on the one hand so cynical and selfish and on the other hand so eager to get excited about apparent miracles.

I think these considerations go a long way toward explaining the strange character of Admiral Kolchak. As I see it, he was just holding the line, waiting for a miracle: the collapse of the Reds; the victory of Denikin; a greater commitment from the Allies. Without such a miracle, victory for White Siberia was not possible, even if Budberg got his way.

Partisans, Frogs and Switchmen

In passing, Budberg tells extraordinary stories, like the tale of a Red partisan group which posed as a White detachment and endeavoured to capture Omsk. Their plan was rumbled by White counter-intelligence but before the Reds could be arrested off their trains, they took off into the wilderness with all the weaponry that had been issued to them. They formed a partisan force threateningly close to Omsk.

Images and turns of phrase which may well be commonplace in Russian strike my mind as powerful and fresh. For some reason, frogs are a recurring image. ‘The Omsk frogs continue to croak,’ he notes, and elsewhere he denounces the Semyonov regime as ‘the Chita swamp and its absurd frogs.’ The Omsk government departments, local in reality but with all the pomp of old Tsarist state organs, are ‘frogs swollen into an All-Russian Ox.’

(Update: a reader has helpfully pointed out that this is a reference to a classical fable – https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Frog_and_the_Ox)

China Miéville in his book October speculates on a strange phrase which occurs in the sources: leftist workers being denounced as ‘switchmen.’ He makes a good case for investing this with significance. The phrase occurs here, in the entry for July 30th. I can’t make out what it means in context but perhaps others can figure it out.

White and Red

It’s interesting to compare Budberg’s diary with Trotsky’s military writings. They faced the same problems: commanders sending in inflated reports, turning skirmishes and panics into great victories or crushing defeats, or soldiers carting along their entire households in long wagon-trains that straggle behind the army. They engaged in the same conflicts with their own respective colleagues: professionalism against guerilla-ism, military science against romantic notions glorifying the offensive.

But Budberg and Trotsky were at odds over the question of whether commanders should go into battle personally. For Budberg, it was stupid demagogy. For Trotsky, it could be necessary in order for the commander to earn his authority.

Capitalist White territory faces the same social and economic problems as Communist Red territory. There is a lack of machinery, of trained professionals and of capital for investment. This leads to bureaucracy, waste and a scarcity of consumer goods (mitigated by the flow of material from the Allies). We are taught in school that these were features of communism, ie, that they somehow resulted from too much sharing. In reality, they are problems of underdevelopment which we see in all countries of whatever social system which find themselves in that historical cul-de-sac.

In other senses White Siberia is distinctly feudal-capitalist. While the quality of the Red forces is pretty uniform (generally mediocre-to-poor), there is a sharp hierarchy of quality between White units. The best are excellent while the worst are of little use, or simply useless, or worse than useless.

The fundamental weakness of the White side is diagnosed:

The filling of the ranks with an unusable mobilization element [ie with conscripts] proved fatal: the heroic remnants of [politically-motivated White Guards] dissolved in the stream of skins.

The phrasing is obscure due to language barrier and the limits of Google Translate, but the meaning is clear: it is impossible for the Whites to build a mass army without fatally diluting their best units. In the Red armies, small numbers of communists proved to be like leavening in the bread, causing the whole mass to rise. But in the White armies, the small politically-motivated element was drowned in a sea of indifference and hostility. This is because the Reds pursued better methods, but more fundamentally because the Reds had a programme that appealed to the masses.

Too clever by half

Another key weakness is explained: that the top brass of the White Army are incompetent whiz-kids, all hype and no substance, who pursue ‘too-clever-by-half’ plans and throw lives and units away. They owe their prominence to the role they played in the semi-guerrilla struggle of summer 1918; they can lead small groups, but have no idea how to assess the fighting strength of this or that unit.

Budberg writes: ‘Siberia fielded not a few thousand young and old knights of duty, pure enthusiasts who raised the sword of the struggle for their homeland.’

But there were no leaders, men of experience and talent, to use these mighty forces; thousands of these fighters are already sleeping in the Siberian land, and all their efforts, their heroic deeds have been brought to naught […]

I envy these fallen ones […]; I ache with my soul for the survivors, for they have had a share of seeing all this and drinking to the bottom of the last bitter cup, not a personal cup, but a Russian cup of grief, shame and death.

The cup of grief overflows

That quote also provides an example of Budberg’s often-excessive prose. Those ellipses in square brackets stand in for text as long again as what is there! He is inclined not only to overwrite, but to repeat the same lamentation again and again at wide intervals, each time with more passion, like a theme in some classical piece. I can see some readers getting annoyed by this. I found it crossed the line into black humour: he keeps lamenting the problems in ever-keener tones of anguish, and things keep finding ways to get worse.

If some publisher decides to put this out in English, they may wish to cut out a few thousand words. Another consideration: I approached this with prior knowledge of the topic, so I was able to follow it easily; to reach a wider audience this source would need to go out armed with a good introduction and copious footnotes.

Go to Revolution Under Siege Archive

[i] I admit, without embarrassment, that I read this text through Google Translate. This programme has come on in leaps and bounds, and I was very impressed with the quality of the translation.