This is Revolution Under Siege, a series about the Russian Civil War. In this post, we will contrast Ukraine in 1919 with 2022. Then we will begin a round-up of some of the array of factions which contended for power in Ukraine during the Civil War.

From April to November 1918 the Ukrainian revolution was left to simmer under the heavy lid of Austro-German military occupation. With the end of the Great War the German and Austrian empires collapsed. Meanwhile the end of the Turkish Empire opened up Ukraine’s Black Sea coast.

The German soldiers cleared out. From the Taman peninsula at the eastern edge of Ukraine, the Germans vanished. ‘They disappeared in the night, quietly, as if they had never been there at all.’ Likewise one morning in Odessa citizens woke to find them gone.[i] It was not so sudden elsewhere; German soldiers would stay behind for a while, would join one faction or another or just try to keep out of it.

Within a few weeks, an array of diverse factions had appeared all over the country, and for a long time no force was able to hold the capital city, Kyiv, for longer than a few months. Nobody could count on their ‘allies’ and nobody was in full control of their ‘own’ soldiers. Suffice it to say that between 1917 and 1920 Kyiv changed hands sixteen times.

Ukraine in 1919 was as crucial as a theatre of war as the Don Country or Siberia. But civil war in Ukraine was even more complex than in Russia.

So this two-part episode takes the form of an explainer. First, we will go into the main ways in which Ukraine in 1919 was different from Ukraine in 2022. Then we will give a run-down of each of the main contending factions.

The current war in Ukraine lends immediacy to this topic. Then, like now, people were dying in terrible numbers in combat; masses of unarmed people were forced to leave their homes; civilians were murdered. The same place names feature, or the same cities under new names.

But if we look at 1919 through a prism of 2022, we will miss some essential points.

- This was a civil war between Ukrainians, with direct armed intervention from a range of other countries including Poland, France, Romania and Russia (both White and Red). It was not an invasion of Ukraine by the Russian state, as we see today.

But even to speak of Russian ‘intervention’ in 1919 on a par with French intervention is not fair, as we will go into below.

2. In 1919 the war was fought primarily on socio-economic questions – workers against bosses, peasants against landlords, peasants against the varicoloured armies which lived by pillaging them. But in 2022, the national question is in first place.

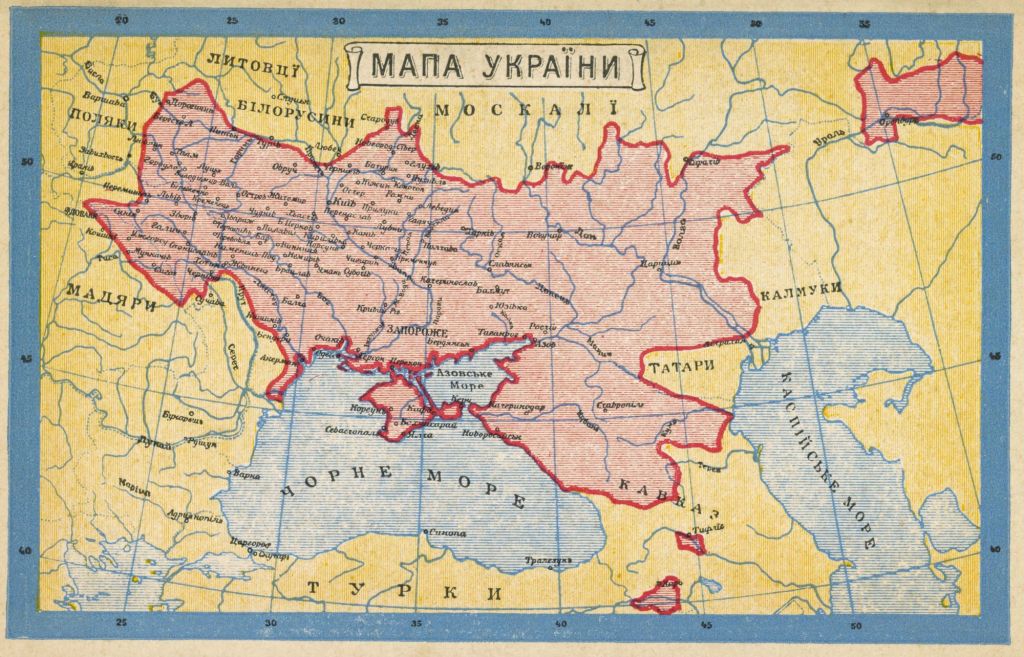

Ukraine, in 1919 as in 2022, is not a small nation. Its language, culture and people suffered vicious oppression under Tsarism. But one-fifth of the Empire’s population resided in Ukraine – 20 million people or even 32 million, depending on how you count them.[ii]

Here we come to another difference between now and then.

3. Ukrainian nationalism in 1919 was simply not the force it is today. In February 2022 when Putin’s regime invaded Ukraine, he probably counted on splits developing within the Ukrainian government, military and society. Over the six months between then amd the time of writing the Ukrainian people have not fragmented under the onslaught, but on the contrary cohered. They got behind the Zelensky government, even though most of them didn’t trust Zelensky before the war.

In 1919 the situation was very different:

[…] enervating to Ukrainian efforts toward statehood was the very weakly developed sense of nationalism in the territories it claimed as “Ukrainian.” Despite the inculcation of Ukrainian nationalism by successive generations of intellectuals during the nineteenth century, few of the region’s numerically predominant peasant population seem yet to have absorbed the notion of a distinct Ukrainian identity by the early twentieth century.

The cities were dominated by Russians and Poles in the civil service and the professions, and by Jewish people in commerce and intellectual life. The urban population was miniscule. Ukraine was a land of farmers and Ukrainian was a language spoken in villages.

In 21st-century Ukraine, 70% of the population lived in cities, and most of those city folk speak Ukrainian. It is a nation of workers and not of peasants. It is ruled not as in the early 20th century by Polish and Russian landlords but by Ukrainian capitalist oligarchs. The classes in Ukraine, the way people live and make a living, the national consciousness, have all changed utterly.

If today Kyiv was only 18% Ukrainian, and many of those 18% spoke Russian and considered themselves Russian, then Putin’s attack on that city would have turned out very differently. But those were the numbers in 1919. In the July 1917 local elections only 12.6% of the vote in small towns went to ‘overtly Ukrainian parties,’ and the corresponding figure for larger towns was 9.5%.[iii]

Unlike today, the idea that Ukraine should be an independent state did not have the support of a critical mass of the people. Among the urban and working-class population, this idea had very little support at all.

4. In 1919 the Ukrainian nationalists did not have the support of the Allies. Today western leaders are effusive in their support for the Zelensky government, weapons have poured into the country, and blue and yellow flags are to be seen across Europe and North America. But in 1919 the Allies were suspicious of the idea of Ukraine being autonomous or independent of Russia. Remember, they hoped to see the White generals win the Civil War. These Whites spoke of Ukraine as ‘Little Russia’ and one of their key slogans was ‘Russia, one and indivisible.’ Why antagonise the White generals by ‘dismembering Russia’?

What was more, in February 1918 the Ukrainian nationalists signed a peace treaty with Germany. For this, the Allies never forgave the Ukrainian nationalists.

So there are some major differences between Ukraine a hundred years ago and now.

Below, our round-up of the various factions that contended for Ukraine in 1919 will further illustrate these points. It is divided into two parts, the second of which will follow next week.

1. The Hetmanate

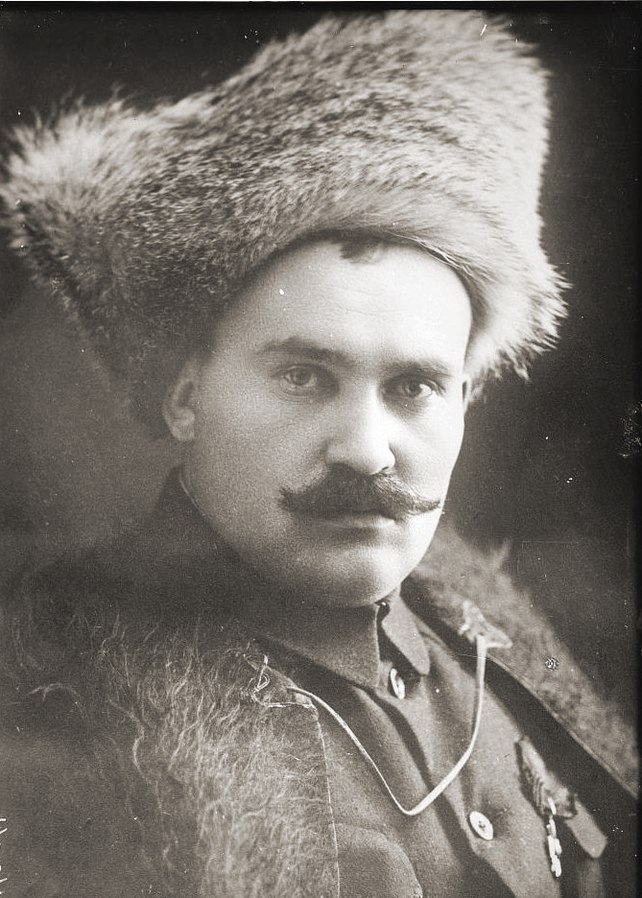

As we have seen, in February and March 1918 the Germans advanced across Ukraine from the West, driving the Red Guards before them. The Ukrainian nationalists, led by Petliura and Vynnychenko, took Kyiv as the Reds cleared out, but soon surrendered to the advancing German military. The Germans tolerated Petliura and Vynnychenko for about five minutes before ousting them in a coup and setting up a puppet government. The leader of this government was Pavlo Skoropadskyi, a Russianised Ukrainian general and a former aide-de-camp to the Tsar, no less. His title was Hetman, which is a Ukrainian term for warlord.

In superficial trappings, the government of Hetman Skoropadskii, known as the Hetmanate, protested its Ukrainian-ness as if to compensate for its subservience to Germany.

The Hetman spoke only a little Ukrainian, and his ministers were from Russian political traditions hostile to Ukrainian liberation: the Costitutional Democrats and the Octobrists. They abolished all of the reforms that had been brought in before the coup, and they banned strikes.

The Hetmanate ‘jarringly bedecked itself with the pseudo-Cossack trappings of a semi-mythologized Ukrainian national reawakening – uniforms, flags, titles and ranks not heard of since the seventeenth century (and some not even then) could be espied on the boulevards.’[iv] The rifleman of the 1st ‘Blue Coat’ Division of the Secheviye Streltsi wore a tall furry hat with a blue flamme, a long blue coat called a zhupan and baggy trousers of seventeenth-century fashion known as sharovari.[v]

But the reality of national oppression is summed up in one statistic: 51,428, the number of railway carriage-loads of grain and other goods which were, with the aid of the Hetman, stolen from the Ukrainian people and taken to Germany and Austria.[vi]

As we have seen, the German empire collapsed in revolution and surrender in November 1918. The pantomime was up, and Hetman Skoropadskii knew it. He cleared out on the next train to Berlin, dressed as a German officer. He made it to safety. Evidently this disguise was more convincing than his attempt to pass as a Ukrainian nationalist.

Most of my sources skim over the fact that there was a serious if brief war between the Hetman and the forces which replaced him, the Rada. In this war, the Allies promised to support the Hetman and even landed 5,000 British troops at Mikolayiv. But they were neutralised by the warlord Grigoriev, who we will look at next week.

2. The Rada

We already saw how in 1917 a parliament took power in Kyiv, calling itself the Rada. It was dominated by liberal and social-democratic Ukrainian nationalists.

Though at first it appeared the Rada and the Soviets might tolerate one another (even after the Rada suppressed the Kyiv Soviet) they ended up at war. The Kyiv Arsenal workers were massacred by the Rada. The Left SR Muraviev (who would later mutiny on the Volga) led a horde of Red Guards into Kyiv with much bloodshed and shellfire.

Then, as we have seen, came the Germans, who first allowed the Rada to stay in power, then had them overthrown in a coup.

The Rada forces led a 30,000-strong rebellion against the Hetman during the summer. Revolts simmered. Partisan forces organised.

After the Hetman jumped on the train to Berlin, ‘a largely peasant army swept Petrliura to power.’[vii] The Rada forces seized Kyiv. This regime was known as the Ukrainian National Republic or the Directorate – but for the sake of clarity and continuity it will be referred to here as the Rada. The leading figures were Vynnychenko and Petliura, two former members of the Social-Democratic and Labour Party. They passed laws nationalising industry and seizing the great private estates of the landlords. But the regime did not have the time or the machinery to implement these reforms, and it was in fact dominated by local military officials.[viii]

In one source we read that they nationalised industry, at least on paper. But in another we read that the Rada was a regime of the military and the bourgeois and professional classes which did nothing to win over the workers and did not espouse ‘social reform on any significant scale, thus failing to rally the peasants.’ These failures were ‘frankly and repeatedly admitted by Vinnichenko [sic]’ who also admitted that ‘So long as we fought the Russian Bolsheviks, the Muscovites, we were victorious everywhere, but as soon as we came into contact with our own Bolsheviks, we lost all our strength.’ Ukrainianisation aroused hostility. Vynnychenko also confessed that the Rada’s political appeal forced the Ukrainian people to choose between nation and class, and the Ukrainians chose class.[ix]

The Rada only remained in power a short time. Just like in 1918, the Rada barely got time to unpack its bags in Kyiv before it was chased out, this time by the Red Army. Petliura fled west to Vinnytsia, ‘where he formed a more right-wing regime purged of Social Democrats and Social Revolutionaries.’[x]

3. The Poles

Ukrainians often have cause to explain to foreigners that there are two, three or more ways of pronouncing their name, or the name of their home town. In Irish terms, it’s like the Derry/Londonderry debate, or when a Seán is pointedly addressed as John, or when a member of the Ward family signs off as Mac an Bhaird. The different versions of names are statements rooted in a history of conflict.

Take one city which is today in Western Ukraine: ‘Lwów (Polish), L’vov (Russian), L’viv (Ukrainian), Lemberg (German) and Liov (Romanian) were all current during the revolutionary period.’[xi] In media reports today it is universally Lviv (no apostrophe).

Let’s go with Lviv. In 1919 it was the chief city in what the Poles called East Galicia and the Ukrainians called West Ukraine. It had been for centuries a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. This empire had all-Ukrainian units in its army. In November 1918, at the war’s end, these Ukrainian soldiers rose up in revolt. They seized Lviv and declared a West Ukrainian People’s Republic (WUPR), allied to the Rada in Kyiv.

But the Polish state newly arisen to the west had designs on the same territory. The WUPR fought a bitter and bloody war for its survival against the new Polish army. The region was stricken by famine in these years as a result of the fighting.

After the Rada was chased out of Kyiv by the Reds in February 1919, they found refuge with the WUPR. But this refuge was worn down by constant attacks from the Reds to the east and the Poles to the west.

In April, Petliura signed away West Ukraine/ East Galicia to Poland in a peace treaty. For this, the WUPR elements never forgave him, and in émigré circles after the war they denounced the Rada as ‘rude, East Ukrainian peasant cousins.’[xii]

4. The Whites

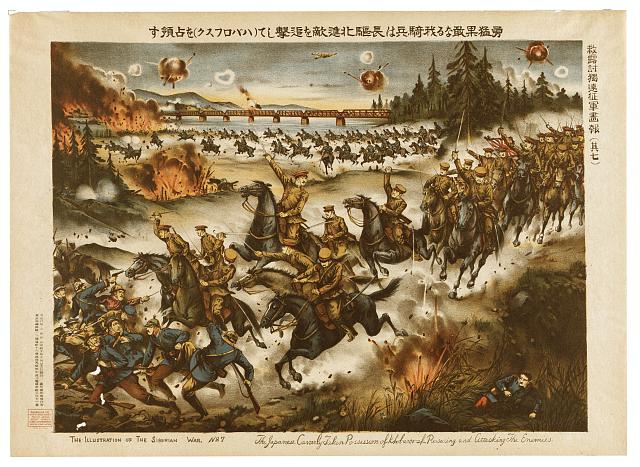

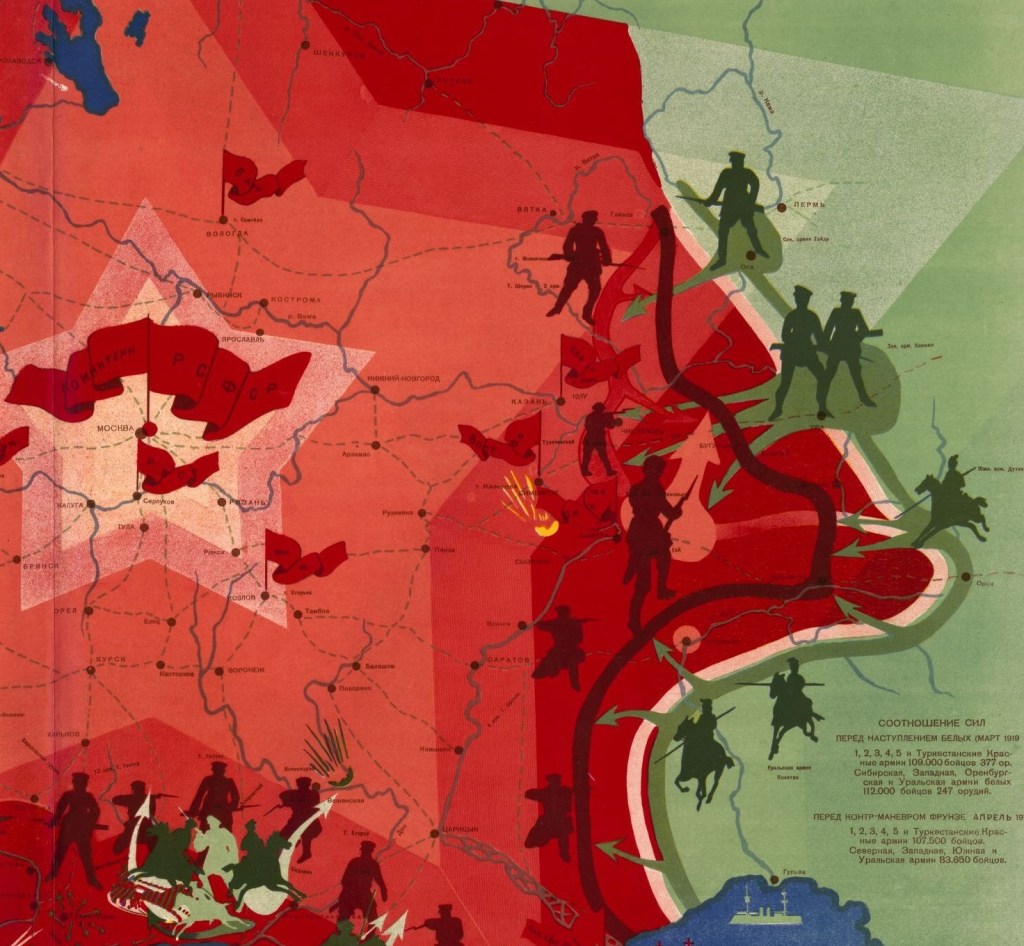

Ukraine bled seamlessly into the Southern Front of the Russian Civil War. Rostov-on-Don today is only a three-hour drive from Mariupol. The Volunteer Army was going from strength to strength in early 1919, and several thousand of these former officers and cadets occupied the Donbass region.

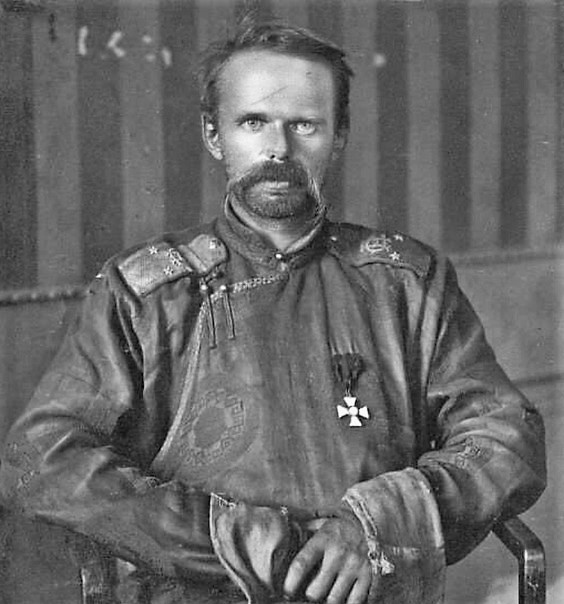

The industrial, working-class Donbass region was not their natural habitat. Their numbers were not impressive. Their commander, General Mai-Maevsky, was a heavy drinker who looked ‘like a dissolute circus manager’ and brought with him a travelling brothel.[xiii]

Yet in the first half of 1919 they held the Donbass against three successive Red offensives. How? Professional soldiers are more mobile than militia, and steadier than partisans. They can wring the maximum out of whatever advantages they possess. In this case British aircraft scouted for the Volunteers, who made good use of the dense railway network of the Donbass. Under the leadership of Mai-Maevsky, who was courageous and brilliant in spite of first impressions, they were able to concentrate their forces at the decisive places whenever the Reds advanced.

The occupation of the Donbass, and the support of the British navy, meant the Whites were a factor in southern Ukraine.

Here we can compare 1919 and 2022. The White programme for Ukraine was broadly similar to Putin’s today: they did not want to loosen their grip on what they called ‘Little Russia.’ As for Lenin and the Bolsheviks, Putin today condemns them for their acknowledgement of Ukraine’s right to its own culture and to self-determination. For him, the prophecies of medieval saints carry more weight than the aspirations of 40 million people who want to live in peace.

Join us again next week for ‘Warlords of Ukraine, continued,’ in which we will look at three more factions: the Reds, the warlord Grigoriev and the Anarchists.

Go to Revolution Under Siege Archive

[i] Antony Beevor, Russia: Revolution and Civil War, p. 255 .

[ii] Smele, The ‘Russian’ Civil Wars, p 96 (20 million); Mawdsley, p 162 (32 million)

[iii] Smele, 98

[iv] Smele, 61

[v] Khvostov, White Armies, p 43

[vi] Smele, 62. When we factor in smuggling, the real number may be twice as high.

[vii] Smith, Russian in Revolution, 162

[viii] Smele, 62

[ix] Carr, The Bolshevik Revolution, Book One, 310

[x] Smith, 186

[xi] Smele xii

[xii] Smele, 152

[xiii] Beevor, 258