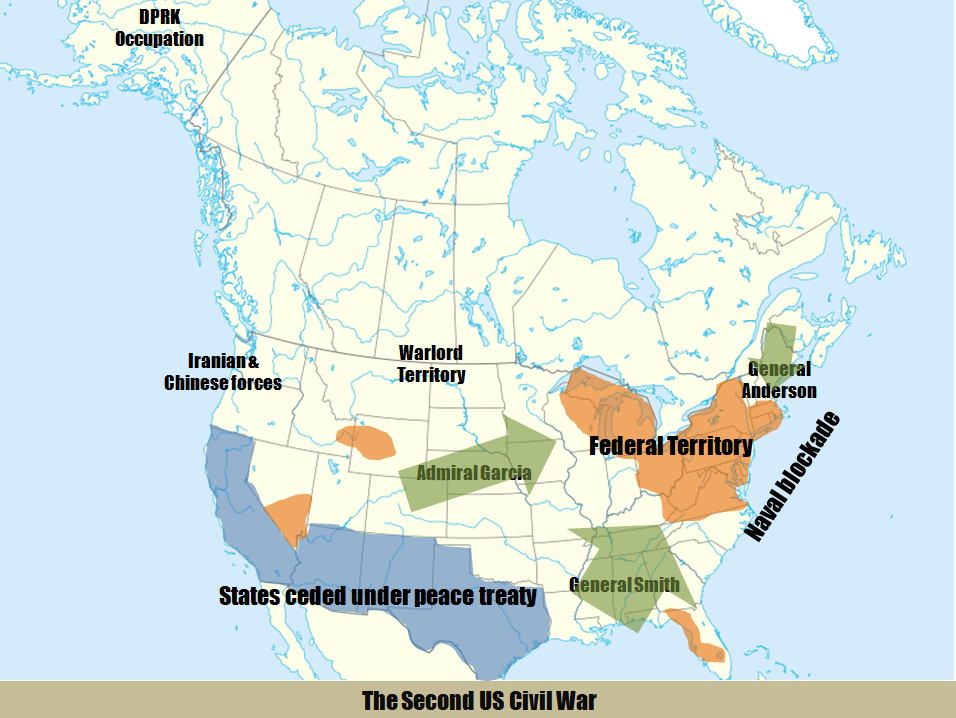

The Red Army drives back the Polish invasion. The Soviet leadership faces a choice: whether to make peace or to carry the war into Poland. This is part 26 of Revolution Under Siege, an account of the Russian Civil War.

‘We are a force in the world, and you are destined for the mortuary. I despise you and hold you in contempt.’ Piłsudski, in a fit of anger, was fantasising out loud about what he would like to say to the Soviets. This was during the months before the Polish invasion of Ukraine. ‘No, no, I have not been negotiating. I have just been telling them unpleasant facts… I have ordered them to understand that with us they ought to be humble beggars.’ [1]

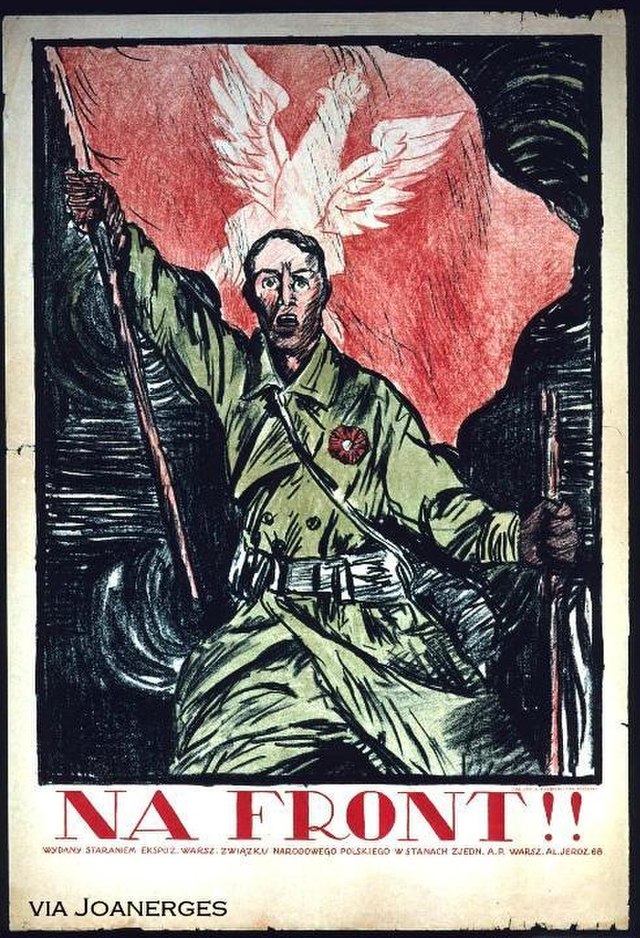

It was indeed in a beggarly and humbled condition that the Soviet Union found itself in a full-scale war with Poland a short while after this outburst. Still, somehow, the Soviets found ways to dig deeper. 280,000 communists joined the Red Army – that was 65% of the party’s membership. A measure of the chaos of the times, of the threadbare state of the new institutions, is the fact that 2.5 million people had deserted from the Red Army over the winter of 1919-1920 – to put that into perspective, the Soviets had over three times more deserters than the Poles had soldiers. But an indication that perhaps the Soviets were not bound for the mortuary after all is found in another statistic: 1 million – the number of deserters who returned voluntarily to the Red Army after the Poles invaded. [2] The war commissar Trotsky toured Ukraine speaking to crowds of deserters, urging them to re-enlist.

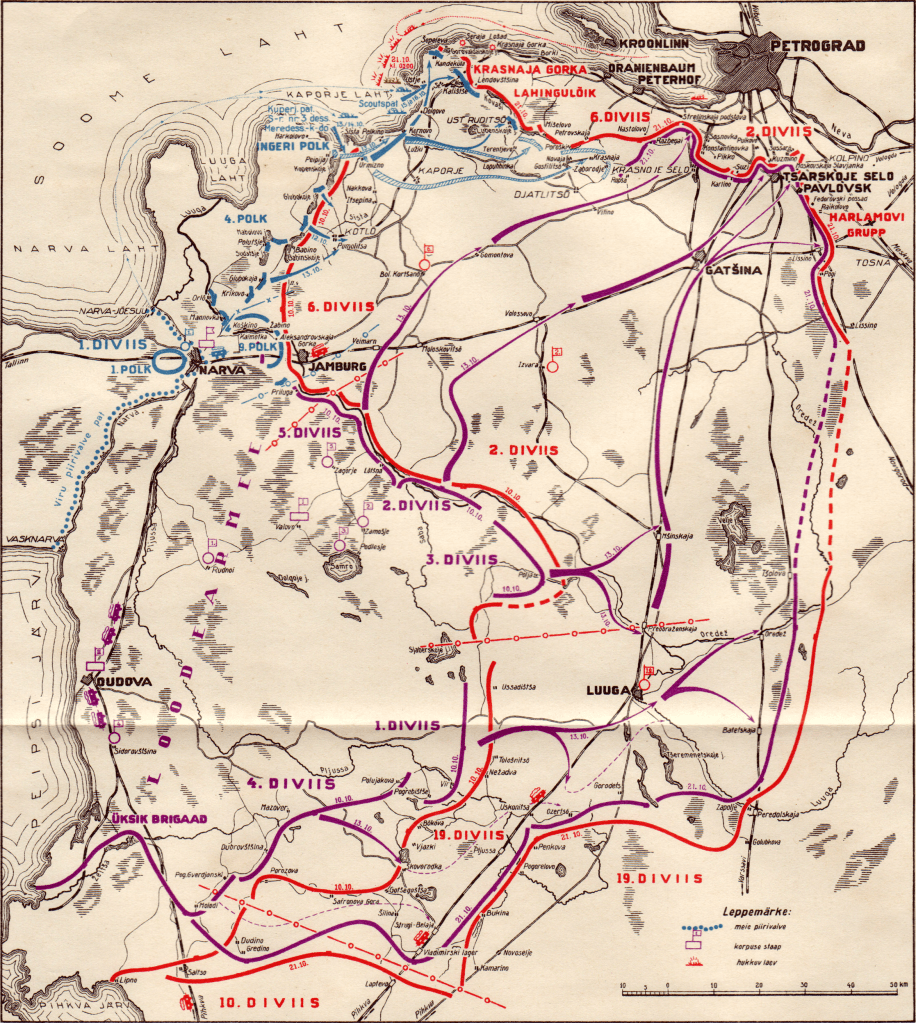

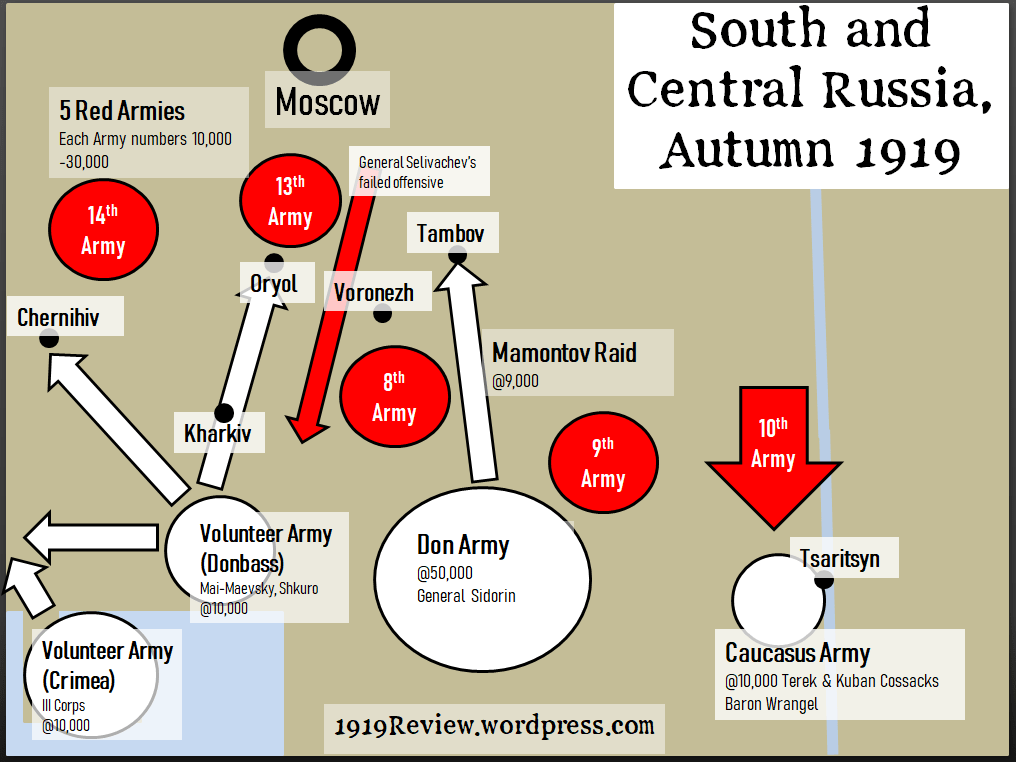

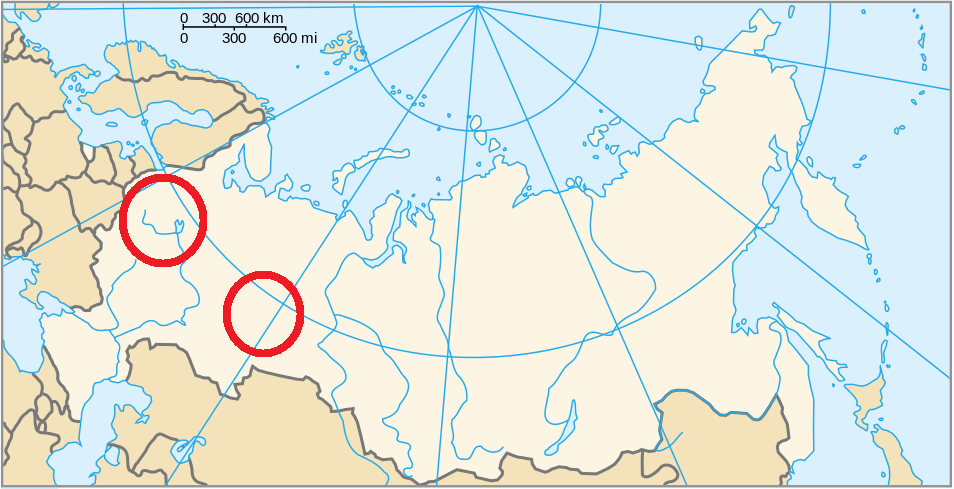

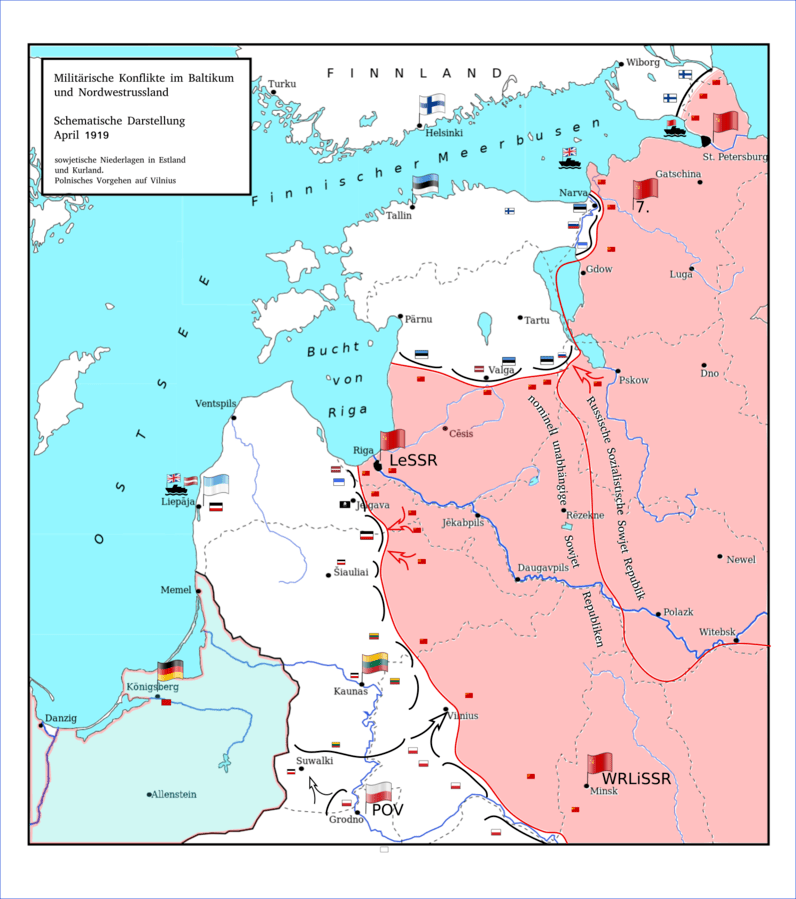

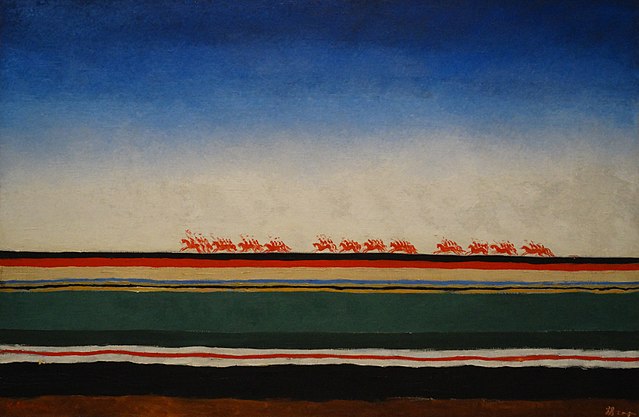

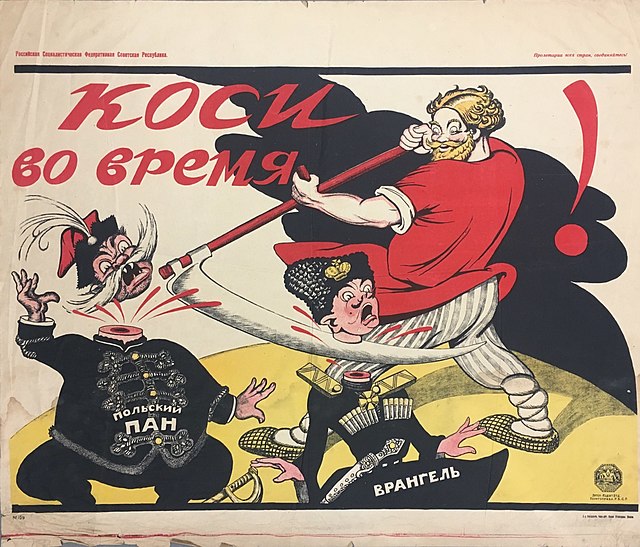

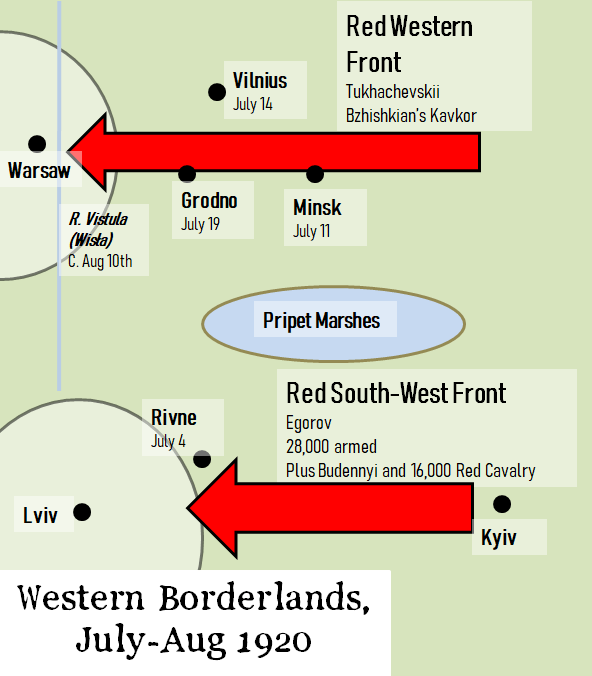

As you are probably re-enlisting as a reader of this blog after a gap of a week or two, here is a reminder that the Polish-Soviet front was divided by the Pripet Marshes into a Northern and a Southern Sector. In the Southern Sector, Budennyi and First Cavalry broke through enemy lines and the Red Army’s South-West Front forced the Polish forces to withdraw across western Ukraine.

Kaleidoscope of Chaos

In the Northern Sector, the Red Army’s Western Front went on the offensive – with disappointing initial results in late May, followed by stunning successes in June and July. Here Third Cavalry Corps, known as Kavkor, played a key role. Kavkor was commanded by a Persian-Armenian socialist named Hayk Bzhishkian.

(This name entered the mangling process of Slavicisation then Latinisation and came out the other end, somehow, as ‘Gay,’ ‘Gaia Gai’, or worst of all ‘Guy D. Guy.’ I will call him Bzhishkian. And if I alienate any readers, I hope it’s because of my long-windedness, my blatant partisanship or my preoccupation with violence, and not because I made you pronounce an Armenian name in your head.)

Kavkor and Bzhishkian advanced on the right flank of the Western Front, where they found weak spots in the overstretched trench lines of the Poles, and broke through before reinforcements could arrive.

Barysaw, where the Polish side had insisted talks must take place, was soon in Soviet hands – what was left of it. The Polish army reduced it to ruins with chemical and incendiary shell-fire. [3]

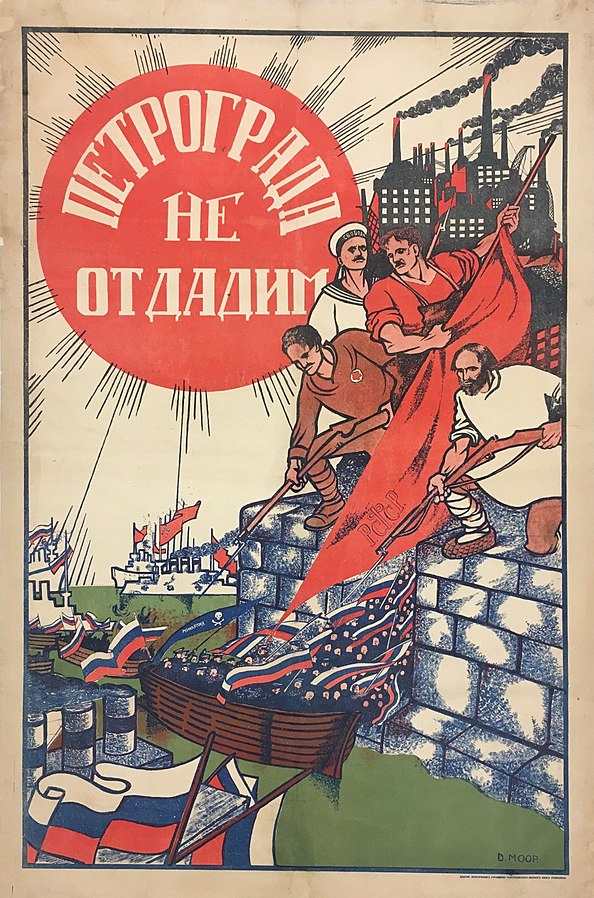

Bzhishkian’s cavalry seized Vilnius. A 14-year-old scout went ahead and reported back key information. Then Kavkor attacked, aided by local communists, and the city soon fell. The Soviets handed Vilnius over to the Lithuanian government, a magnanimous gesture that ensured the Baltic States didn’t join in on Poland’s side. And at Brest-Litovsk, local Polish communists played a key role in aiding the Red Army.

Piłsudski called the Polish retreat ‘a kaleidoscope of chaos.’ If you look at the Battle of Grodno, you can see what he meant. Here 500 Polish uhlans, an entire regiment, were swept away and drowned while trying to cross the Niemen River.

As at Petrograd and in the South, the Red Army at the Battle of Grodno had to face tanks kindly supplied by the Allies: some were mobile, some were able to fire but were stuck on their transport train.

A frightened soldier shouted to Bzhishkian: ‘Tanks, comrade corps commander! How can one sabre them when they’re made of steel?’

Another cavalryman added: ‘Bayonets are no use; in any case you can never get near them.’

But the cavalry surrounded the French Renault tanks and forced them to retreat, playing for time as the steel monsters were disabled one by one: by artillery, by collisions, by breakdowns and by lack of fuel. Only two escaped across the burning bridge over the Niemen.

‘An armoured tank is nothing to frighten a skilled cavalryman,’ wrote Bzhishkian of the experience in his 1930 memoirs. [4] He would not live to see World War Two and history’s final judgement on that question.

The Polish retreat was chaotic but, Davies points out, tenacious. The most spectacular battles were on horseback; Russian sabres were sometimes defeated by Polish lances. On one occasion a Polish cavalry division commander personally defeated and killed his Soviet counterpart during a battle which delayed the Red advance by two or three days.

Nonetheless the movement was all in one direction, and to the Polish soldier, in Piłsudski’s words, the Soviet advance was ‘like a heavy, monstrous, uncontainable cloud.’ [5]

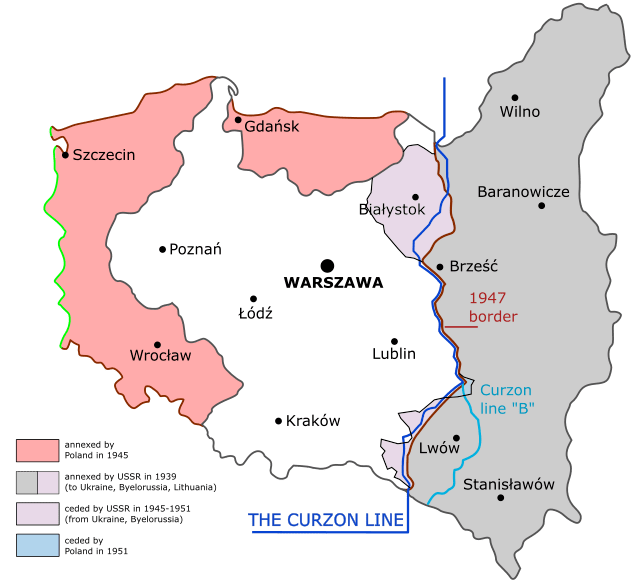

The Curzon Line

On July 11th the Allies tried to step in with a peace proposal. [6] Imagine a posh English politician gesturing at a map and saying, ‘Pans, comrades, why not draw the Soviet-Polish boundary just here.’ This here was known as the Curzon Line. It gave the Soviets a lot more territory than they had when the Poles first attacked, and also gave the Poles a lot more than what they stood to lose if Bzhishkian and Tukhachevskii kept advancing.

The Allies proposed this border because they still believed the Soviet Union would collapse and be replaced by a conservative Russian Empire, and they were keen to establish relatively generous borders for their hypothetical future ally.

Whatever the motivations of the Allies, it suited the Polish government to quit before they got any further behind, and they agreed. [7]The offer was Moscow’s to take or leave – not humble beggars anymore.

The Soviet leaders entered into a debate, dynamic as was the Bolshevik tradition but short and to the point. The question at issue was whether to launch a counter-invasion of Poland or, having repulsed the Polish invasion, to make peace. Unhelpfully, the British tacked on a provision that the Soviet Union should recognise Baron Wrangel and let him hold onto Crimea, which Moscow would never do.

On either July 16th or 17th, Trotsky on behalf of the Red Army command made the case for accepting the peace proposal – though he never accepted the point about Wrangel. Rykov, Radek, Stalin and others also opposed crossing the Curzon Line. Of Radek, Lenin later said, ‘I was very angry with him, and accused him of “defeatism”.’ [8] Lenin was in favour of advancing on Warsaw, and so were most of the Polish communists resident in Russia.

The Debate

The broad arguments of the two sides – let’s call them the peace party and the war party – are laid out below in the form of a dialogue, in my words. Where I am directly quoting, I have indicated it using inverted commas.

War:

We have been subjected to a full-scale invasion. We have driven back our enemy, but if we do not pursue him to his lair and finish him off, he will strike again. Just look at what happened in South Russia – how many times did we have to fight our way across the Don and the Kuban? And now Wrangel is trying to raise the Kuban in revolt yet again. Woe to he who does not carry matters to a finish! We have every right to invade and to destroy this regime of criminal military adventurers, who have brought so much suffering and destruction on the working people of Soviet Ukraine and Soviet Belarus.

Peace:

From a military perspective, to invade Poland is insane. It is not like Denikin or Kolchak; it is not a question of fighting officers, undisciplined Cossacks and raw conscripts. We face 750,000 Polish troops. It is ‘a regular army, led by good technicians.’ Even if the Red Army takes Warsaw, its supply lines would be stretched too thin to occupy Poland for long. [9] The Soviet Union is crying out for peace. We won’t survive another winter of war. Hunger and disease will be rampant. The regime may even fall apart.

War:

We do not assess these problems purely from a military perspective. It is not a question of conventional war or occupation. The mass of the Polish people, the working class and poor peasantry, will join us in our war against the Polish landlords and bourgeoisie.

And we must also consider the perspective of world revolution. In Britain the ‘Hands off Russia!’ campaign is making headway; on 9th and 10th May, British dockers refused to load munitions onto a ship bound for White Poland. There is a developing revolutionary situation in Italy, with soviets in Turin and factory occupations; and in Germany we’ve seen the defeat of the Kapp Putsh by a workers’ general strike and even the organisation of a workers’ Red Army in the Ruhr. If we defeat Poland, we open the way to Germany, and may trigger revolutionary events there and elsewhere. Imagine if Budennyi or Bzhishkian arrived in Berlin just on time to prevent another massacre of communists like that of January 1919.

We also want peace. But this latest onslaught by the Allies shows that they are hell-bent on our destruction. We cannot hope for peace except by breaking out of our isolation.

Peace:

The Polish workers and poor peasants are unlikely to join us. By pursuing the Polish army into Poland, we will drive them into the arms of Piłsudski and his military-Bonapartist clique. It is still the honeymoon period of Polish independence. Resentment of all things Russian is still understandably strong. ‘This is the historical capital from which ‘Chief of State’ Piłsudski hopes to draw interest.’ [10]

We too see the perspective of world revolution. But if we are defeated, it will be a setback for the revolution everywhere.

War:

The key question, then, is the attitude of the Polish masses. The Polish revolution has always marched in step with the Russian; our anthem ‘Varshavianka’ refers to the Polish revolutionary tradition. In 1905 the Poles held out for longer against the Tsar than the workers of Moscow. In 1919 there were reports of Soviets in Cracow. [11] There were ‘village republics’ where the farmers took collective control of the land. On May Day this year, the demonstrations in Warsaw, Łódź and Czechostochowa were anti-war and anti-government – remarkably, a mere week after the beginning of the Polish invasion. A railway strike in Poznań, beginning the day after the invasion, turned into a week-long pitched battle between strikers and the authorities. [12]

The reports from the Belarussian Front have been most encouraging. Arrogant Polish landlords return on the coat-tails of their army and try to grab the land, and this angers the people and the rank-and-file soldiers. The Poles barely hold the frontline zone, which is traversed freely by refugees, deserters, bandits, petty traders, cocaine dealers and Polish Communist partisans. We have reports of mutinies and of harsh reprisals by Polish officers against the men – including executions. More recently, Polish soldiers returning from leave are condemning Piłsudski as the puppet of the landlords and questioning the aimlessness of the war. On July 26th an infantry unit rose from their trenches singing The Internationale and preparing to cross over to us; they were only prevented by their own side opening fire on them from behind. [13]

And we have many talented Polish communists here in Russia, who are enthusiastic to carry the revolution to their homeland; on May 3rd 90 Polish delegates met in Moscow. In Kharkov and Smolensk we have printed masses of material in the Polish language – 280,000 copies in Smolensk alone. We will guarantee the Polish worker, soldier and farmer an independent Soviet Poland. We even have a Polish brigade, 8,000-strong, on our Western Front, to form the nucleus of a Polish Red Army.

Peace:

Taken as a whole, the indications are not nearly so favourable. The Polish Socialist Party received only 9% of the vote in January 1919. The Polish Communist Workers’ Party is illegal and has very little support in Poland.The Cracow Soviet was put down. The ‘village republics’ were suppressed with draconian severity. The Piłsudski government is Bonapartist in character; it does not simply represent the landlords or the bourgeoisie, but tries to play a balancing act. It has embarked on land reform of its own accord, which saps the agitational strength of our land programme. The Polish landlords who are trying to claw back parts of Belarus and Ukraine are supported by the Polish officers, but opposed by government agencies [14].

The Polish soldier on the Belarussian Front is demoralised, it is true. But the Polish soldier defending the approaches to Warsaw may prove to be a more formidable opponent.

To invade would not hasten revolution – it would delay it. We cannot tolerate Wrangel in Crimea for a moment longer than is necessary – on that we agree. Let us then focus as much of our strength as possible on Wrangel. But let’s talk to the Allies, and agree on the Curzon Line as our border with Poland.

The Advance to Warsaw

Intra-Bolshevik debates were often conflicts between audacity and caution. Today audacity won out. All agreed that the Soviet Union could not build socialism in isolation from the rest of the world. The key strategic imperative was to break out. Up to this point it was assumed this would happen through an indigenous revolution in another country, but this war represented another kind of opportunity. The war party won the vote, and the Red Army was ordered to sweep on into Poland.

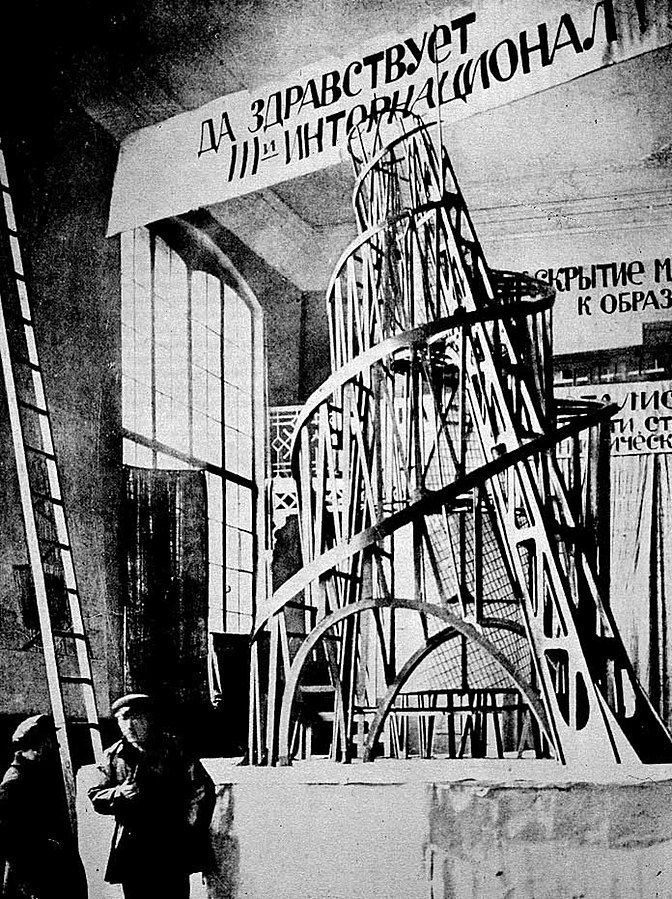

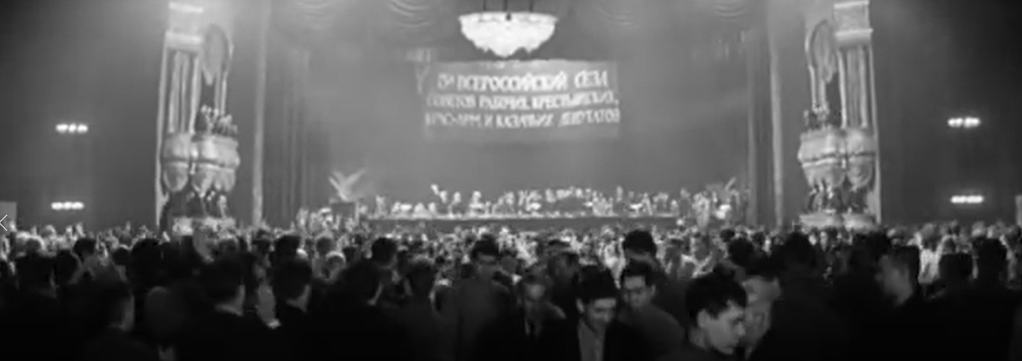

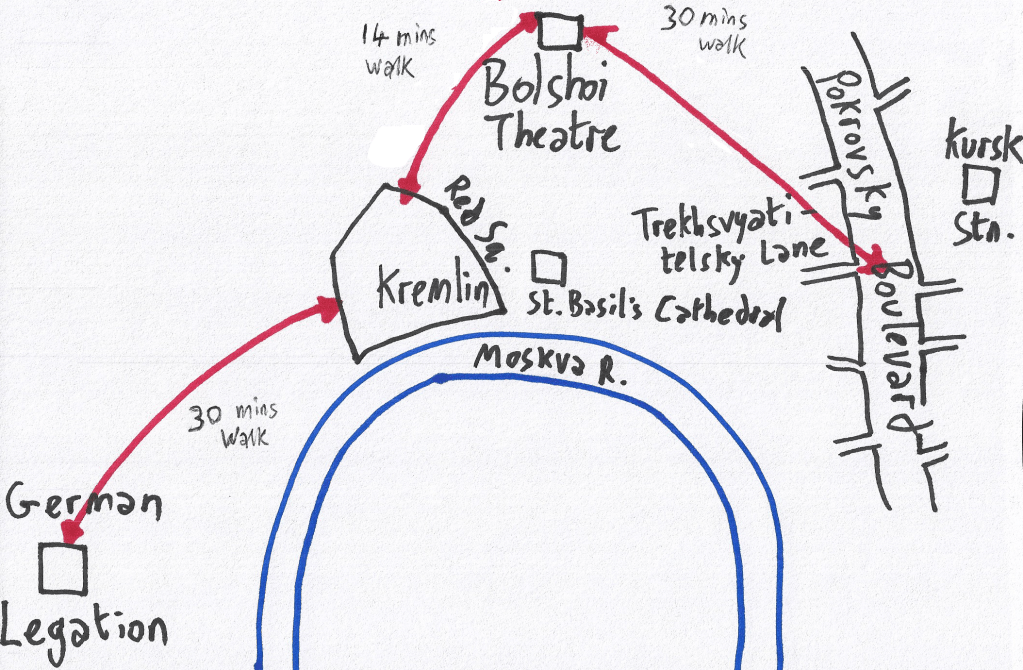

From July 19th to August 7th the Communist International held its Second Congress, a bigger and more impressive affair than the First Congress back in March 1919. Among the 220 delegates was Alfred Rosmer who has given us an often-quoted description of a large map of Eastern Europe that was on display outside Lenin’s office. Visitors watched as little flags were moved across it to mark the positions of the armies; in July, all the red flags were moving west. ‘The advance of the Red Army was stunning; it was developing at a pace which nonplussed professional soldiers ,as only anarmy born of revolutionary enthusiasm is able to do.’ Tukhachevksii’s Western Front took Minsk on July 11th, Vilnius on July 14th, Grodno on July 19th, crossed the Bug River on August 1st and by August 10th was closing in on Warsaw. [15] Some of Hyak Bzhishkian’s Kavkor had in fact run on ahead, west of Warsaw.

In the Southern Sector, the Red Army captured Rivne and Kamianets-Podilsky on July 4th. Budonnyi is reported to have said that if he had as many riders as the old Tsarist army – that is, 300,000 – ‘I would plough up the whole of Poland, and we would be clattering through the squares of Paris before the summer is out.’ For better or for worse, he had only 16,000, which along with the Red Army’s South-Western Front, aimed to capture the city of Lviv.

What struck Rosmer in a conversation with Lenin, however, was how the Soviet leader was just as interested in what he had to say about developments in the French Socialist Party as he was in Poland. For Lenin, then and always, it was all one struggle. [16]

In August 1920, the crux of that struggle lay not in the Ruhr Valley or the factories of Turin but on the Vistula River. The humble beggars had come to Piłsudski’s doorstep.

References

- [1]Davies, p 74

- [2] Davies, 142

- [3] Trotsky, How the Revolution Armed, Volume 3,‘Postal Telegram No 1886-B’

- [4] Davies, p 148

- [5] Davies, p 148

- [6] Smele, 156

- [7] Mawdsley, 349

- [8] Zetkin, Clara. Reminiscences of Lenin, January 1924. International Publishers, 1934. ‘The Polish War.’ https://www.marxists.org/archive/zetkin/1924/reminiscences-of-lenin.htm#h04

- [9] Numbers from Smele, 165; ‘good technicians,’ Mawdsley, 255

- [10] Trotsky, How the Revolution Armed, Volume 3,‘The war with Poland – reportMay 5th’

- [11] Read, 111

- [12] Davies, 113

- [13] Davies, 78-91, 151

- [14] Davies, 82-3

- [15] Smele, p 156

- [16] Rosmer, Alfred. Lenin’s Moscow, 1953, Bookmarks, 1971. P 52-53. Budennyi quote from Davies, 120