Warhammer 40,000 has surged in popularity in the 2020s. It has broken into the United States, and there has been a new proliferation of videogame adaptations. A couple of years ago Amazon bought the rights to make a TV show set in the grim, dark future in which this tabletop wargame is set, which has led to speculation and discussion about what such a show would look like. I decided to share my thoughts, and they ended up being a meditation on the unique appeal of this hobby and setting.

Don’t make it about the Space Marines…

We do not know if the Warhammer 40,000 TV series will actually be made. But I have a dreadful premonition that if it is made it will turn out to be mostly lads in power armour doing stilted dialogue in front of fuzzy CGI landscapes.

The Space Marines are good for miniature wargaming: chunky, iconic and with cool abilities. But I can’t imagine them making up a good cast of characters on TV. If the camera has to linger on them for longer than a few minutes they will get really boring, really fast.

By definition they are all ultra-zealous supersoldiers, and I don’t see much dramatic potential there without really stretching the bounds of the setting. I fear the screenwriters will stretch it and break it, resorting to the war movie clichés, and there will be a streetwise city Space Marine and a naive farm-boy Space Marine, a Space Marine who is a petty thief and pedlar, a fat clumsy Space Marine, a nerd Space Marine, a Space Marine who shows people a picture of his girlfriend back home, etc. There might be room, maybe, for one religious Space Marine. Stock characters are not necessarily a bad thing in general, but they won’t work as Space Marines.

The other problem with the Adeptus Astartes is that they would cost an absolute bomb to put on the screen. How are they going to lumber around on set with any comfort or dignity in all that massive armour? If it’s light enough for them to wear, the weight of it won’t sit right, won’t look good; if it’s heavy enough to look convincing the actors just won’t be able to do it. CGI will have a lot of sins to cover up, and there goes your budget.

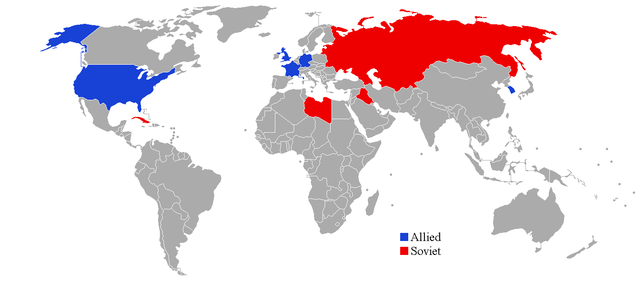

So who should the TV show be about? Easy: the Astra Militarum, aka Imperial Guard, because they are relatable and human but exist on a sliding scale of weirdness. They can be stock war movie characters, or they can be the Death Korps of Krieg, or anything in between. The writers have more freedom. Costumes and kit would be much cheaper: extras could be army reservists from whatever country they film in, maybe even, if we are really short of funds, wearing their actual uniforms, decorated of course with plenty of skulls and aquilas. They are canonically multi-racial and multi-gendered, so you could cast these characters pretty much any way.

The Tau would be another faction that could be interesting to show. Avatar shows that it can work when you base a story around blue and heavily made-up and CGI’d aliens who are still humanoid and relatively sympathetic. Some similar points apply to the Aeldari. But the Astra Militarum would be so much more straightforward.

…but have Space Marines in it

But the Adeptus Astartes are iconic. They have to be in the show, or people will feel cheated. Here’s an easy solution: include them. Have a squad or a company of them, and make them secondary characters. We see them for 5-10 minutes in each episode, and in the finale they stomp in and help turn the tide. The less we see of them, the cooler they will be. Also, if they are not the main characters, you can make them as weird and fanatical as they should be. You can also spend plenty of money to get them right, because you would make savings based on their limited screen time.

Tell a (relatively) small story

Warhammer 40,000 is a famously baroque and extravagant setting. Aside from half a dozen human factions, we have Chaos, Aeldari, Drukhari, Orks, Tau, Necrons, Tyranids and Leagues of Votann. At that, I’ve probably missed a few. Each faction has its strengths and weaknesses and its aesthetic. Then within each faction, we have numerous sub-factions (Goffs, Bad Moons, etc for the Orks; Aeldari Craftworlds, cults of Chaos). And each sub-faction has its strengths and weaknesses, aesthetic, etc too. Even after all that, there are more than enough lacunas in the lore for players to make up their own craftworld, Space Marines chapter, Astra Militarum regiment, etc. Each faction has dozens of troop and vehicle types, each with its own set of stats and rules and its own intricate resin miniature; the hobbyist glues each miniature together from parts and then paints it according to their own creative vision.

I think it’s the medium of the tabletop wargame that gives it the freedom to get so weird and wide-ranging. Novels have to be focused on character and plot, TV shows more so, movies most of all. You might see elaborate worldbuilding in, say, a very long series consisting of very long books (George RR Martin), an open-world videogame (Fallout: New Vegas) or in a sprawling comic that runs for decades (Marvel, DC). But a tabletop wargame is even more freed from the constraints of character, plot and narrative focus.

A novelist has to think about how to work in some backstory or try to make the exposition more interesting. Warhammer hobbyists are happy to buy army books in which (alongside rules, tips, artwork, etc) platefuls of backstory and exposition are served up without any attempt at “working them in subtly.” It’s open-ended; it’s better if it doesn’t go anywhere. No hero is going to come along and fix this horrifying future. The point is that the setting is suitable to have a battle in.

What does all this mean for a TV show? Pitfalls. The writers will have to convey a sense of that breadth and depth while also telling a cohesive story. A lot of Black Library material is sprawling and epic in a way that would not translate to the small screen. There are over fifty books in the Horus Heresy series! So I hope they don’t try to tell *the* story of Warhammer 40k, with the Emperor and the primarchs as characters. The fall of Cadia would be another dangerous one to try. These kinds of stories would cost too much, and be too solemn and gargantuan to give new audiences a point of entry.

Think smaller. Stick to one planet, or even one city or one battlefield. ‘Thinking small’ in the context of 40k could still encompass a gigantic city with lots of ecclesiastical mega-architecture, or an arsenal-moon with a gun cannon bigger than Australia. A hive city would allow for a good mix of studio interiors and miniature or CGI exteriors.

Here are ideas of the kind I think could work:

Inquisitors investigate a Genestealer cult. A full-scale Genestealer rebellion breaks out later in the season. After the Imperium forces win in the final episode, we strike a fatalistic note with the discovery of an approaching Tyranid hive fleet, of which our Genestealer cult was just a forward outpost.

A group of civilians and assorted imperial soldiers are trapped behind enemy lines by a sudden enemy advance and fight a partisan war.

Imperium and Eldar/ Tau/ Votann forces are forced to bury the hatchet and ally against a Chaos onslaught that threatens them all. The grim, dark, fatalistic note could sound when it ends with the trial and execution of our main character on charges of working too closely with xenos.

Use what you’ve got

A simple story set in a limited location allows for the more full building of a world. In a film like Children of Men, the most important things accumulate in the background or in brief glimpses. The visual and auditory richness of that movie shows what could be possible in a 40k series.

It is already such a visually rich world. A TV show would have an absolute wealth of material to draw on. No need to reinvent the wheel in terms of costumes, decor, set design, etc. Give us half-robotic flying cherubs and guys with pipes sticking out of their faces. Give us flying buttresses and computer terminals set into ornate pulpits, and skulls everywhere.

Get it right

I talked earlier about how 40K is open-ended, that there’s no real need for narrative focus as far as the tabletop wargame is concerned. But it would be a big mistake to think this means it’s shapeless or meaningless. What 40K does have is a distinct aesthetic and tone (maximalist, gothic, totalitarian, grotesque, with a hint of satire), plus rules that are (of necessity) pedantically exact. This provides a backbone to the sprawling lore. Its not that there’s ‘no point’ to the lore or backstory or that it ‘goes nowhere.’ If I’m building an army of Chaos Marines who worship the plague god Nurgle, I’m going to assemble them so as they look diseased and paint them in sickly greens. If I have an army of Orks I know they are very poor shots with ranged weapons but strong in hand-to-hand; my tactical challenge is to get them to close in on the enemy fast. Good thing I have some Stormboyz, ie, Orks with rockets on their backs.

So the lore is not arbitrary or pointless. It gives purpose to the hobbyist and clear rules to the gamer.

A TV show would have to get such details right. There is room for great variation in the 40k Galaxy, but if we see Orks who are crap at close quarters combat, or Nurgle Marines with a general air of good health, that will be a problem.

Another pitfall would be if the story and setting are played straight. The Imperium of man is a monstrous society, combining the 17th Century wars of religion with the height of Stalinism. Please understand before you begin that a Space Marine is not a US Marine in space. He is what it would look like if Buzz Lightyear joined ISIS.

We identify with the Imperium because we see in it something of ourselves, even though that something is a savage caricature of human history’s most repressive and fanatical tendencies.

And in turn, isn’t Chaos just a caricature of the Imperium? Maybe if imperial citizens weren’t primed and traumatized their whole lives by the grotesque imperial cults, they wouldn’t find the Chaos gods so appealing. If life wasn’t so miserable in the Imperium, maybe its people wouldn’t regularly see guys who look like Mad Max villains crossed with actual maggots and say, “Where do I sign up?”

A vein of fatalistic humour should run through this grim, dark story. For tone, think along the lines of Paul Verhoeven, Mortal Engines, Judge Dredd and Fallout (well, West Coast Fallout, not East Coast Fallout, which is an instructive example of inappropriately playing it straight). It’s not Star Wars. And on the other extreme, we don’t want ten hours of 300 with boltguns.

A related idea: what if the series was a straight adaptation of an existing Black Library novel? I actually have a specific one in mind. But I’ll leave that for another post. Stay tuned. Meanwhile share your own thoughts in the comments. What faction should a TV show focus on? Is there any book you’d like to see adapted? Can you see a way small-screen Space Marines could work?