I’m folding my promised conclusion on Dr Zhivago into this broader post on history in movies, dealing with it along with Kingdom of Heaven, Platoon and A Complete Unknown.

There was a game called Commandos 2 (Pyro Studios, 2001), a stealth adventure set in the Second World War. The game’s own manual contained a long bullet-point list of its own inaccuracies, ranging from ‘the bridge on the River Kwai was made of metal, and it was never blown up’ to ‘there are no penguins at the North Pole.’ It has stuck in my mind because I’ve never seen anything like it since, not in movies or games or TV shows, though now and then the afterword of a novel will include one or two confessions. But what an excellent idea: for a text to own its inaccuracies, to be deliberate about them, to signal, “What you are about to experience is part fantasy.” It takes a lot of confidence and maturity for the authors to risk undermining their own authority like this.

I wonder why this isn’t standard practise, why no government has obliged producers of historical movies to release an ‘accuracy statement’ for me to pore over. Maybe the answer is that a lot of history is open to debate, so these statements would open a can of worms. In a recent series I asked of the 1965 epic movie Dr Zhivago, ‘is it accurate?’ I couldn’t answer that question without getting into my own opinions and understanding of the era.

It’s not as simple as asking ‘Did what happens in X movie actually happen?’ The answer is going to be ‘mostly, no.’ But here are some questions to which we can give more interesting answers: ‘What is this movie saying about history?’ ‘How well is it getting this message across?’ and ‘Is that message accurate and fair?’

Dr Zhivago

Let’s ask these questions of Dr Zhivago.

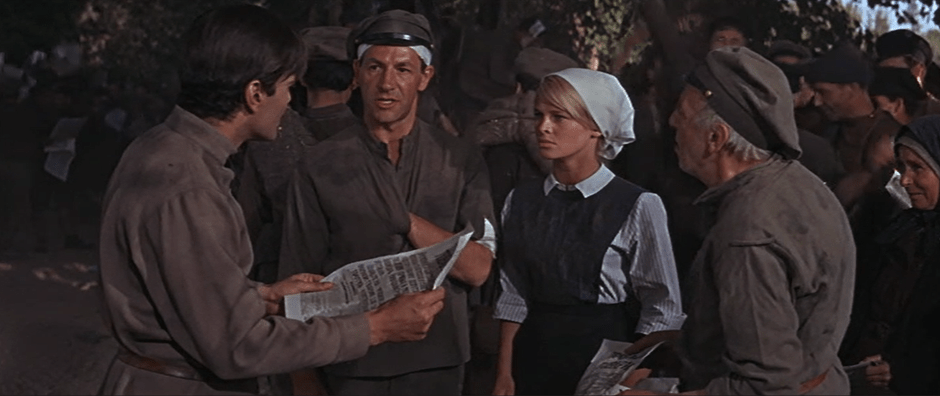

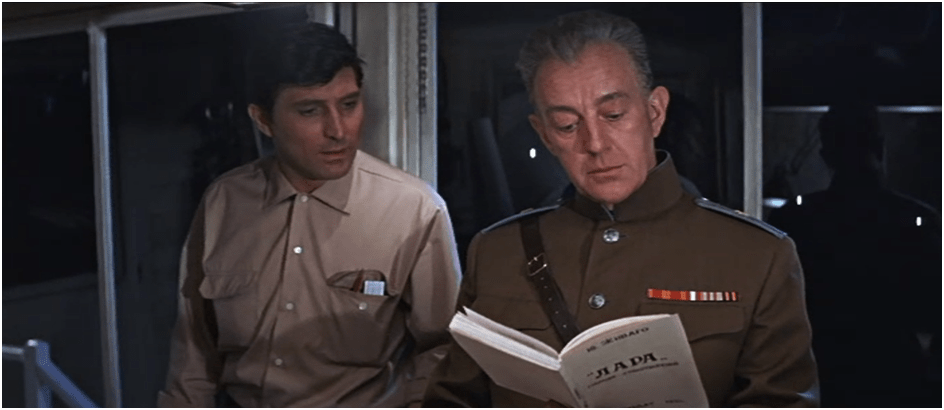

Parts of it are very good – individual monologues, scenes and images convey significant historical events in a dramatic, emotional, visual way. For example, I like how the Moscow street changes over the course of the movie. I mentioned Yevgraf’s monologue. It’s good that we have armoured trains, even though they are in the wrong place and time. This film gives us a strong sense of place, especially in the haunting train journey sequence. It is lavish in supplying the sets, crowds and explosions that give a sense of mass participation in events, of sharp conflict. Its slow pace and the care it takes to root us in its spaces are refreshing in the context of a lot of today’s cinema, with its short scenes and rapid cuts (see Oppenheimer, which I’ll mention later too).

I think that historical movies have their value even when they are inaccurate. They furnish the public with reference points (oh yeah, Roosevelt, the president from Pearl Harbor), and even when these reference points are good only as punch bags for criticism (Gladiator makes a mess of Roman-era battles, but here’s what they really looked like) they are performing some service in that at least. If scholars of history don’t criticize these movies, especially movies we like, we are missing an opportunity to teach. So even as I criticize Doctor Zhivago I cut it plenty of slack. Compared to a lot of other movies that bill themselves as historical, it’s solid enough.

The screenwriter, Robert Bolt, was a former communist who maintained links with the British communist party until 1968. I think this helps explain a lot about the movie: the way it humanises the revolutionaries, the care and feeling in the writing. Maybe this script represents Bolt, through the avatar of Yuri, getting over (or at least coming to new terms with) his love affair with October (Ten years later he wrote a two-act play about Lenin which I am curious to read).

The film appears to advance a thesis about the Russian Revolution: that while it was a natural response to Tsarist tyranny and war, it was itself tyrannical and violent – worse, that the Revolution represented the antithesis to individuality. I don’t agree with this view (you can find a lot of my own views here) but I assume you didn’t ask; the interesting question is whether the movie adds up to a good argument for this view.

The Squid Game Baby Civil War

I don’t think it does. The movie’s message impressed me more when I knew less about the real history. I’ve already noted how many times Yuri is confronted by a mean Bolshevik or Bolshevik-adjacent person who is contemptuous of his poetry. In these conversations (first with Kuril, then Yevgraf, then Antipov, Razin and finally Komarovsky) the movie’s case is stated explicitly: that Yuri himself, his private life and his creative output are not compatible with the revolution. The movie is here overplaying its hand because Yuri is actually an understated, inoffensive, decent person, not a wild man or a troublemaker. So what people say about him does not accord with what we see. The theme has to be stated so bluntly in dialogue, again and again, because we don’t see it organically.

The movie presents the Revolution and its supporters generally in a negative light. To do so it too often it relies on exaggerations or inventions, or a collapsing of the timeline that goes beyond reasonable limits. This is a common failing in historical movies: the writer (who is working to industry deadlines and specifications) puts in what they assume was there and what the producers and audience expect to be there. So within weeks of the October Revolution we see a poet exiled for ‘individualism.’ A few weeks later we have villages burned by an army which wasn’t there as a punishment for aiding another army which also wasn’t there.

As regards the Civil War, we get some striking images but little sense of the whole to which they belong. The war enters and exits the stage according to the needs of the narrative, not according to its own logic. This reminds me of something more recent: in the third season of Squid Game we have a miraculous baby who never cries or needs to be fed, or even opens its eyes; its function is to be cute and vulnerable, to add tension to the bloody contest. The Civil War as presented by Dr Zhivago is like the baby in Squid Game. The war adds tension, and we are periodically reminded that it’s there (even before it’s there) but when it isn’t immediately needed, it is docile.

The movie as a historic event

A movie is a big undertaking and, more so than a book, its production and reception constitute historical events in themselves, and you have to be clear on whether you’re talking about the movie as a movie or the movie as an event. Let’s illustrate what I mean by straying over that line in relation to Dr Zhivago. Here I’m far more critical.

What was courage on the part of Boris Pasternak – writing a novel about Russia’s revolutionary years that dissented from the enshrined narrative – is on the part of western filmmakers not courage but complacency, because they are promoting a narrative that’s not at all controversial in their own part of the world. Pasternak doesn’t need to remind his Soviet readers that the Whites were powerful and reactionary, that the Reds brought about popular reforms, or that intervention happened; Soviet readers have heard all that a hundred times before. But Dr Zhivago’s cinema audience in the west is unaware of these parts of the context. And the movie goes further: it treats the revolutionaries with far less sympathy than the novel and makes key changes, such as Yuri being exiled from Moscow and Lara being anti- instead of pro-Bolshevik.

The Russian Civil War, like Dr Zhivago, was an international affair. This film was a US-Italian co-production with an English director and writer, filmed in Spain, Finland and Canada. Why is that important? Because the United States, Italy, Britain and Canada all intervened in the Russian Civil War, all kept it going long after it should have settled down; because the White Finns committed a terrible slaughter against the Red Finns in 1918; and because Franco, a fascist dictator who killed several hundred thousand people with the explicit purpose of preventing an October Revolution in Spain, was still in power when this movie was made there. The apparent complacency of the western filmmakers is really something worse: they are throwing stones in glasshouses.

To me, this underscores the way the western powers intervened, escalated the war, armed a large cast of horrible characters, spread famine and disease, then walked away and forgot all about it. The oblivious moral comfort of it all strikes me as an injustice.

I don’t think you have to be from a group (say, the Russian people) to write about that group. But if you put yourself in this position, you do have a lot more work to do to get it right. This movie wasn’t made with such an understanding. Few movies were in 1965.

You could argue that Bolt as a former communist is in some way a member of the tribe he depicts. He has, I guess, some kind of vulnerability here. It does come across in the writing and to some degree mitigates the complacency, the obliviousness, that I’m complaining about.

Kingdom of Heaven

Scholars of history still only know about a few topics. For example, I thought Oppenheimer (2024) was very good but I wouldn’t be much help to someone who wanted to know if it was accurate.

Kingdom of Heaven (2005, dir Ridley Scott) is a good historical movie, as far as I can tell (I can’t remember what’s in the Director’s Cut and what isn’t). In the broad brush-strokes of the story it tells, it corresponds to the books I’ve read on the Crusades and some scenes follow the primary accounts very closely, such as the scene where Saladin (Ghassan Massoud) offers a refreshing drink before personally executing Reynald de Chatillon (Brendan Gleeson). Balian of Ibelin (Orlando Bloom) is changed from an older, well-established power-broker in the Crusader States to a newly-arrived and penitent young knight who has an affair with the king’s sister. This change is so obvious, and at the same time historically inessential, that there is no concealment going on there, no sense of dishonesty.

There is a good example of where it simplifies history within reasonable limits: when Saladin took Jerusalem in 1187 he enslaved that part of the population which was not ransomed in a complex process; Kingdom of Heaven does not get into the weeds but presents the essential point, that Saladin spared the population from a massacre and most of them walked away with their freedom and all with their lives.

But there are individual lines that are pretty ridiculous. David Thewlis’ character says, ‘I don’t place much stock in religion.’ Dude, you’re a Knight Hospitaller in the 12th Century. You’re half-monk, half-knight and the only reason you live in this part of the world is because the Bible happened there. All your stock is in religion. Also, he’s not a merchant so I feel ‘stock’ is an ill-fitting metaphor.

Let’s consider the theme and this movie as an event. Kingdom of Heaven, considered as a statement on the War on Terror, is interesting. Robert Fisk reported on a screening in Lebanon where the crowd performed a spontaneous standing ovation following a scene where Saladin reverently places upright a crucifix which fell over during the siege of Jerusalem. I don’t know if this Lebanese audience was mostly Muslim or mostly Christian, but either way the reception is moving.

I read the film as liberal imperialist (we can all get along within the status quo), and personally I’m anti-imperialist (we can’t get along so long as the colonisers remain in charge of this land). But the film makes its case well. It presents two political tendencies within the Crusader States that really did exist. The faction around Balian had a more diplomatic and pluralist vision for the future of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, as opposed to Reynald and Guy who were aggressive and chauvinist. The parallel it suggests with the liberal and conservative wings of the pro-war coalition in the US in the 2000s is reasonable. There’s a lot of invention here, but in a medieval setting where we have scant records this is necessary. Screenwriter William Monaghan did a good job.

Now, you’d want someone like acoup.blog to tell you if the armour and tactics in Kingdom of Heaven are right. I’m mostly talking broad strokes.

Platoon

Platoon (1986) is an interesting one. I’ve read a few memoirs of US soldiers in Vietnam (If I die in a combat zone by Tim O’Brien and Chickenhawk by Robert Mason) and this movie is really true to those firsthand accounts. Director Oliver Stone was, of course, basing the story on his own experiences. It’s a highly authentic reflection of the experiences of US soldiers in the Vietnam War.

That’s the problem, too. How fair a reflection of the real history is it if we get a lot of movies from the US side and almost none showing the Vietnamese side? Millions of Vietnamese died compared to 58,000 US personnel; the Vietnamese still have landmines and the effects of Agent Orange. There’s just no comparison. The Vietnamese are not really humanised in most of these movies either.

Credit here to Oliver Stone, who gave a Vietnamese perspective in other movies he made. Further, he had a valuable story to tell in Platoon, and someone else couldn’t have told it and he couldn’t have told some other story in the same way. He does put Vietnamese people front and centre in the terrifying scene in the village, where we come within a hair’s breadth of something like the My Lai massacre.

But the issue stands. There are a lot of great movies about the Vietnam War but this is a hard limit to how great they can be as historical movies given this major problem.

A Complete Unknown

I have some thoughts on the Bob Dylan biopic A Complete Unknown (2024, dir. James Mangold) that are relevant here.

This is another topic I’ve read about, and in my judgement A Complete Unknown is a very fine example of how to condense the messiness of recorded history (or in this case biography) into a dramatic and entertaining story. Dylan (Timothé Chalamet) gets a ‘composite girlfriend,’ Sylvie (Elle Fanning), who is mostly Suze Rotolo but also not; like with Balian, the movie is changing something without trying to fool us. The theme is well-grounded in real history and it lands powerfully. Dylan, like most of his generation, entered into the struggle for a better world but ultimately walked away. Those who tried to badger him into staying there against his will come across badly, but it’s left open for the viewer to make up their own mind what they think about Dylan.

I was mildly disappointed that we didn’t get to see Phil Ochs (except indirectly, when Joan Baez sings a cover of his song ‘There but for Fortune.’) We see a lot of Pete Seeger and a good bit of Johnny Cash and a couple of glimpses of Dave Van Ronk. If you ask me, Phil Ochs has far more business being in this movie than Johnny Cash does. He would be a powerful foil to Dylan, but I suppose that function in the story is carried out more than adequately by Joan Baez and Pete Seeger.

So Phil Ochs should be there, but the movie is busy enough as it is. The movie has simplified things within reasonable margins. *Huffs* I guess.

The above points suggest a few rules for historical movies, some positive, some negative:

- If you find a good dramatic scene in the primary sources, absolutely use it (Saladin killing Reynald, Bob Dylan visiting Woody Guthrie).

- If you want to change things, be obvious about it (Orlando Bloom, Suze Rotolo).

- Simplify events within reasonable limits (Jerusalem 1187).

- Ask if the world needs to hear this story (again) or if there’s a more valuable angle you can take.

- You can tell other people’s stories, but only if you do the homework.

- You probably shouldn’t make a moral judgement on a nationality which had basically no input in the production – but if you must, then find a way to make yourself and your audience vulnerable.

- You can do parallels with today, if they actually fit and you do the work to show how they fit.

- Your movie benefits from using a historical setting, but you have to pay the overheads. For example, if you want to have knights in your movie, don’t let any of them say ‘I don’t place much stock in religion.’

- If you have to exaggerate and invent to make the theme land, you’d want to ask yourself if the theme is valid.