“…throughout all the difficult days of the dissolution of Antiquity, we can trace the hard, selfish interest of a comparatively small group of families, their wealth and interest founded on land.”

-JM Wallace-Hadrill, The Barbarian West: The Early Middle Ages AD 400-1000. Harper Torchbooks, 1962

The book quoted above fell into my possession a little while ago. Knowing full-well that it was short, very broad, and decades out of date, I still read it with interest.

Men supposedly think about Rome every day. As for me, I’ve read some Robert Graves and played a lot of Total War (never as the Romans), but I’m not especially interested in togas and scutums and senators. But the stuff a little later, the great churn where the senators and castrums are turning into dukes and castles (but aren’t in any particular hurry) are more interesting to me. I like the times when years have three digits and there are a lot of things they haven’t invented yet, like chivalry, or Switzerland, or monks who had to keep it in their pants.

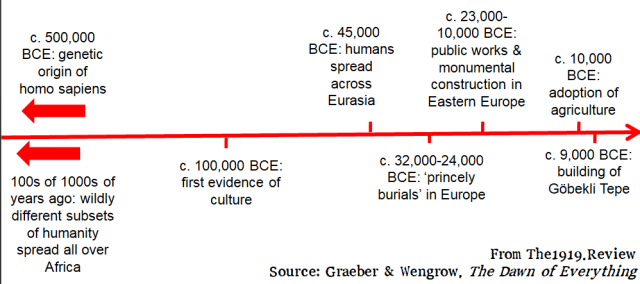

Today people put Rome and the Middle Ages up on a pedestal. But focus your eyes on where one is dissolving into the other, and it all looks more accidental and contingent, and you start learning things, often things you don’t know what to do with, facts you don’t know where in your brain to file.

I read indiscriminately about late antiquity and the early Middle Ages, and every so often I’m going to be posting about what I’ve learned. I might criticise what I wrote here in a future post when I read something else; or someone in the comments may have something to say. No worries. So here are some interesting things I found out from Mr Wallace-Hadrill and his book The Barbarian West.

Did ‘barbarians’ actually sack Rome? (p 25-27)

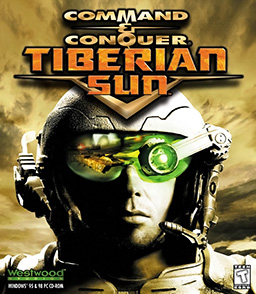

I’ve seen the paintings. I’ve played the videogames. I grew up with a vague sense that there was a day when a horde of savages broke into Rome and burned a lot of nice buildings and murdered a lot of cultivated people, after which there was no more Western Roman Empire and Rome itself was finished as an imperial city.

Wallace-Hadrill says that the Goths took Rome in 410 CE, but did not actually sack it. They wanted food and land, and had no incentive to sack the city. It was back in Roman hands soon after. In 456 there was a serious sack of Rome – not by a nomadic horde, but by the powerful kingdom the Vandal invaders had established in North Africa. It was a sack, but it wasn’t the end of the Western Empire. That didn’t come until 476 and the overthrow of the last Western Emperor by one of his own Hunnic generals, Odoacer.

So the image of ‘barbarians’ sacking Rome doesn’t really convey how it all went down. Both Roman and invader by and large preserved Roman laws and institutions and even language – Latin itself had split into the dialects that would become French, Spanish and Italian before the fall of the Western Empire.

The later Magyar invaders, it is argued, did more damage in Western Europe than the Huns, while the twenty-year attempt by the Eastern Roman Empire to reconquer Italy brought about more destruction than the Huns, the Goths and the Lombards.

The Roman Empire did not fall because of ‘decadence’ (p 10-13)

Why did Rome fall in the first place? On the internet and occasionally in print, I’ve seen people blame it on too much partying, too much sex, too many feasts, orgies, etc. Too much dole. Too much immigration. ‘Weak men create bad times’ etc, etc. If the commentator even notices the gap of centuries between supposed cause (vague ‘decadence’) and effect (fall of Rome), he is not remotely embarrassed by it.

Wallace-Hadrill sums up the 4th-century crisis of the Roman Empire in a few paragraphs. In that century, land was falling out of cultivation in all provinces, a sure warning of the collapse to come. Why?

The most striking point is that the people themselves were driven to revolt by intolerable conditions. We have slave revolts and disaffected farmers turning to “mass brigandage.” Later in the 5th century we have a Roman leader, Aetius, actually allying with the Huns to crush a massive popular uprising in Gaul (Aetius at other times allied with Goths against Huns and with Huns against Goths).

Farms had fallen behind because the whole system rested on enslavement, which held back new inventions and kept agriculture primitive. So from its backward agricultural economic base, the Empire couldn’t pay for its legions or for the palaces and luxuries of its ruling class. The vast external border was too expensive to defend properly. The expense was not just in money, because war casualties and conscription drained the labour force.

All in all, we get a picture of a system that has been pushed far past the limits of its own rules. Its drive to conquer others has led to overstretch and its reliance on enslaved people has led to stagnation. It’s not that the Roman ruling class ‘abandoned their virtues’ or that ‘good times created soft men.’ The problem was that the Roman landlords stayed true to their supposed ‘virtues,’ ie, to a system built on enslavement and conquest, even when it had ceased to deliver the goods on its own terms.

Western Christianity started out as African Christianity (p 14-15)

At first, Christianity didn’t take off in the Western Roman Empire. The aristocrats remained pagan; it was artisans and bourgeois in cities like Milan and Carthage who turned to Christianity. In the East, it was closely associated with the Emperor and with the state. What eventually spread in the West was a version of Christianity that took shape in the Roman provinces of North Africa, a more strict interpretation that defended spiritual power against secular power, ie church from state.

The early Catholic church is full of surprises (p 48-52)

Early Christianity is a bit surprising. The first monastic community at Monte Cassino in the 6th Century was disciplined, but not ascetic. They all had wives and children. Rather than a place of quiet contemplation, it was a kind of bunker in a country torn by wars and plagues. As I said, this period is interesting to me because there are little surprises that I’m not sure what to do with.

In the seventh century we have Pope Gregory the Great. This pontifex maximus was last seen in the pages of The 1919 Review cruising the slave markets and cracking feeble puns about how good-looking the enslaved people were.

Here he appears in a different light. Presiding over a period of chaos, war and plagues, Gregory brings in a system of expensive and effective poor relief. “The soil is common to all men,” declared Pope Gregory. “When we give the necessities of life to the poor, we restore to them what was already theirs – we should think of it more as an act of justice than compassion.”

Couldn’t have put it better myself. I’m nearly tempted to let him off the hook for the ‘Not Angles, but Angels’ thing.

Illiterate Kings

Charlemagne unified France and you could argue he founded Germany. He was a lawmaker and a patron of arts and religion. He converted the Saxons to Christianity at the point of a sword. A formidable character. But here’s a humanising and poignant detail about him from page 109. Wallace-Hadrill quotes a chronicler named Einhard as he goes on about how great Charlemagne was, how generous he was to the priests and to the arts, the churches he built, the treasures he bestowed. Einhard also says that Charlemagne kept tablets and parchment under his pillows so that when he got a free couple of minutes “he could practise tracing his letters. But he took up writing too late and the results were not very good.” He was a king from a line of kings – but in this age, he never got an opportunity to learn to write. He wanted to – but he was too old when he finally got the chance, and he only got to practise in odd spare moments. Even his flattering chronicler Einhard, looking at the messy lines and errors in Charlemagne’s uncertain script, has to purse his lips and shake his head sadly.

To finish, I want to note that books like this don’t come out anymore. And that’s for better and for worse. For better, because the author can be a callous prick sometimes. The later Merovingians died young of illnesses, so they were, he says, ‘physical degenerates.’ Sorry, what? But also for worse. This book is pocket-sized, accessible, unpretentious, erudite, focused. No hype, no bloat. An expert is informing the scholar or the layperson, and Harper are taking in $1.25 into the bargain.

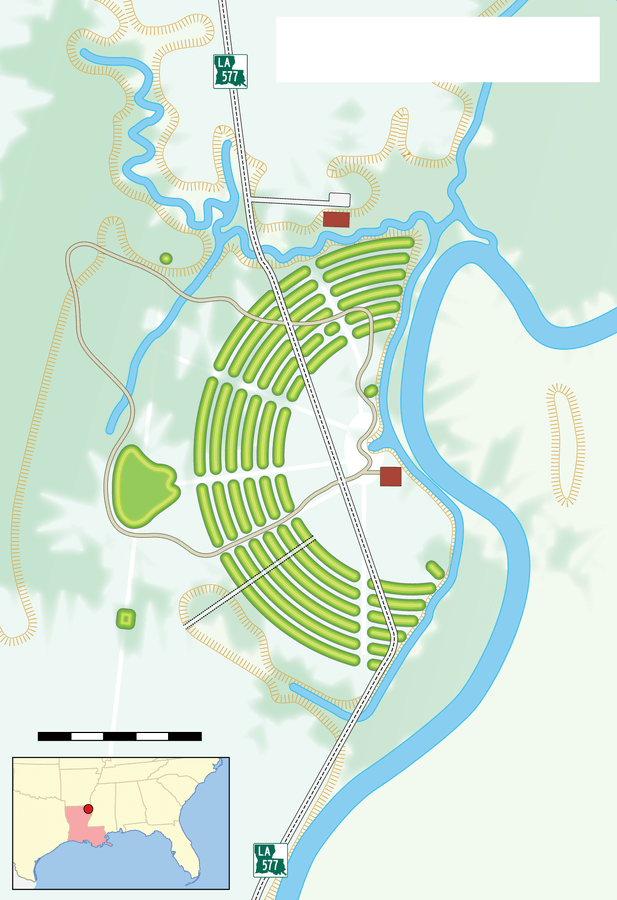

So, Notes on the Medieval World isn’t really a series, more a theme I’ll be coming back to between long gaps, whenever I happen to finish a relevant book. Most likely the next one will be Passages from Antiquity to Feudalism by Perry Anderson. Stay tuned to see what videogame screenshots I manage to shoehorn in.