Review: Prevail by Jeff Pearce, Simon & Schuster, 2014

Prevail by Jeff Pearce is about the Italian fascist war in Ethiopia in the 1930s. Pearce deals with the 1935-6 invasion, the guerrilla struggle, the British intervention and liberation in 1941, and the global impact of the struggle.

This book is important because the Italo-Ethiopian War is often reduced to a bullet point on a list of ‘events leading up to’ the Second World War, or as an episode in the history of appeasement, with the camera focused on white diplomats tugging their collars. In this book the white diplomats get some attention, but the focus is on African protagonists and their epic struggle against conquest. No doubt there have been other good books in English about the war, but I haven’t happened across them. Neither has popular culture, with the exception of Bob Marley, brought it to the attention of the English-speaking world. Eurocentrism has cheated us of a fascinating story.

I hadn’t really read anything on this topic before, so below is a list of twenty interesting facts I learned from Prevail. I hope they give you an appetite to read further.

The Invasion

1. The Ethiopian armed forces were made up primarily of the retinues of petulant aristocrats. These guys were wedded to obsolete modes of warfare and refused to submit to any general plan. At one point the foot-soldiers, when they managed to storm some Italian position, ran all the way back to the rear just to throw trophies at the feet of their emperor – to his immense frustration! It was these organic weaknesses, as much as the shortage of modern weaponry, which made the war an unequal struggle.

2. Emperor Haile Selassie was a retiring and dignified character, to the point of being frustratingly passive at times. But in his modesty he is a foil to the strutting and ranting Mussolini, and at one point in the war he did personally mount an anti-aircraft gun and fire on Italian bombers.

3. The Italians justified their war by claiming they wanted to end slavery in Ethiopia. Humanitarian intervention, in other words. Plus ça change…

4. The fascists started the war by engineering stage-managed ‘incidents’ where they could semi-plausibly claim to have been attacked by Ethiopian troops. Japanese imperialism performed the same tricks in China at the time.

5. After starting the war, the Italian state angled for international sympathy by promoting atrocity stories. One Italian pilot was shot down and his grisly fate at the hands of enraged locals was made into headlines. Meanwhile the Ethiopians were being killed in their thousands. Plus ça change…

6. The British and French diplomats sold Ethiopia down the river. Mussolini admitted in 1938 that if the British government had closed off the Suez Canal, the invasion simply could not have gone ahead. They didn’t even have to start a war with Mussolini! Why did they sell out Ethiopia? One answer is appeasement. But in addition, they didn’t want to support an anti-imperialist struggle which might give dangerous ideas to their own imperial subjects.

Global Impact

7. The war was seen all over the world as a proxy struggle over racism and imperialism. Thousands marched against the war in Harlem, New York. There were protests in Ghana (Gold Coast), South Africa, and many other places. News from Ethiopia would trigger brawls and riots between Italian-Americans and African-Americans.

8. A year before the International Brigades were recruited to fight in Spain, thousands of Black people from the US volunteered to fight in Ethiopia. As the last independent country in Africa, Ethiopia was a potent symbol of resistance to white supremacy – even if as an absolute monarchy it was an unlikely icon for progressive forces. But very few of these volunteers ever made it there; the US government cracked down hard.

9. Two Black aviators made it from the US to Ethiopia. One was a prima donna and con artist, the other a dedicated and brave pilot who would go on to fly Haile Selassie’s personal plane throughout the 1935-6 struggle.

Occupation and Guerrilla Struggle

10. The Italian occupation in Ethiopia was incredibly racist, brutal and vindictive, even by the low standards of European imperialism in Africa. There was a massacre of one-fifth of the population of Addis Ababa when the Italian troops and their allies were given three days to loot and destroy the city. this was a reprisal after the Ethiopian resistance tried to assassinate a top Italian official.

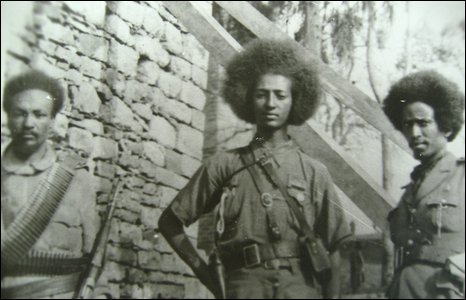

11. Guerrilla struggle continued after the defeat of the Ethiopian armed forces in 1936 right up to 1941. Groups called the Black Lions and the Patriots (Arbegnoch in Amharic) carried on a struggle from remote areas. Some key leaders were women. The young men grew massive afros.

12. Sylvia Pankhurst, who was previously well-known as a suffragette and communist, became the foremost champion of the Ethiopian cause in Britain. She printed a newspaper documenting Ethiopian resistance victories. It’s difficult not to admire her dedication to internationalism even though it seems she was uncritical of reactionary features of Ethiopian society. On her death she was given a state funeral in Ethiopia.

13. The Ethiopian war was a key moment in history for other socialist, black freedom and pan-African leaders. Pearce cites the contemporary writings and activities of CLR James, Kwame Nkrumah, Marcus Garvey, Leon Trotsky and many others.

14. Josephine Baker, an African-American singer who was one of the most famous people in the world at the time, made a vocal statement in support of Mussolini’s invasion. Pearce explores the possible reasons for this bizarre action.

15. Haile Selassie lived in exile in England from 1936 to 1941 and allegedly snubbed Marcus Garvey.

Liberation

16. World War Two changed the political landscape and made Ethiopia a soft spot for the Allies to strike blows at Italy. Britain and France, remember, controlled all the surrounding countries as imperial colonies. Even so, intervention was grudging, delayed and under-funded.

17. The British intervention was led by some glorious English eccentrics and consisted of just 2,000 guys – Sudanese, Ethiopians and British. But they brought supplies, arms and trained military specialists to the Ethiopian resistance, which transformed the situation. It was not an easy struggle, but the Italian forces were overstretched and hated by the local people. They were defeated quite rapidly.

18. After liberation, the British state set about looting everything they could get their hands on – treasure, machinery, vehicles, etc. They stripped bare an already underdeveloped country. Selassie was further enraged by Ethiopia’s treatment at the hands of the Allies. Even though they died in their thousands in the anti-fascist struggle, the Ethiopians were not recognised as a constituent part of the Allied cause.

19. Selassie gave little reward to the youth who had made up the ranks of the Patriots. Ethiopia remained a very conservative and stagnant society under his rule – though the impact of war and occupation could not have helped in its development.

20. During the war, the Italian fascists looted a huge monument called the Aksum obelisk, which stood in Rome for decades. It was only returned to Ethiopia in 2005 – a symbol of how unrepentant the powers-that-be in Italy remained for a long time after the whole brutal affair.