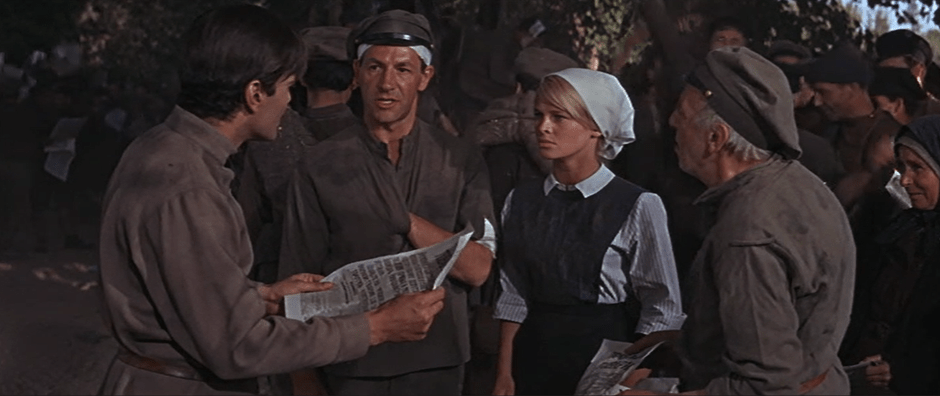

From the back of a lorry, men in red armbands throw leaflets to a cheering mob of soldiers. The unit’s doctor, Yuri Andreievich Zhivago (Omar Sharif), is handed a sheet by a bewildered illiterate elder.

‘The Tsar is in prison,’ Yuri reads aloud. ‘Lenin’s in Moscow!’ He looks up and adds, ‘Civil war has started!’

Yuri Zhivago and his unit are a little out of touch. Russia’s Tsar Nicholas II was arrested in March 1917 (Gregorian calendar), Lenin arrived in Russia in April 1917 but did not go to Moscow until early 1918, and the Russian Civil War started in May 1918. Yuri appears to be catching up on fourteen months of news. Word travelled slowly in revolutionary Russia, but not this slowly.

Most of the movie is not this bad and parts of it are pretty strong. I’m inclined to be generous to Dr Zhivago, a 1965 historical epic directed by David Lean, because the movie is generous to the viewer, serving up crowd scenes, spectacular landscapes and big, painful emotions.[i]

But this single line of dialogue is a succession of statements each of which is more jarring to my ears than the one before. It’s like someone scrolling on their phone and declaring, ‘A new coronavirus has broken out in China. American police have murdered George Floyd! Trump supporters have tried to stage an insurrection in New York!’ Note that I’ve got the city wrong and that I assume someone who’s just heard about COVID 19 somehow knows who George Floyd is.

Then again, maybe we will be watching that movie in fifty years.

The verdict of historian Jonathan Smele on Dr Zhivago is not generous: he notes that it is pretty much the only movie in English about the Russian Civil War, which is a shame because it is ‘mostly lamentable’ even though it’s ‘admirably snowy.’[ii]

Smele did not elaborate, but I’m going to,[iii] probably at length, over two or three posts.

This movie was enormously successful and popular at the time of its release. It raked in five Oscars and a ton of money. Very few English-language films have tackled the October Revolution and, aside from this and Warren Beatty’s Reds, none that I’m aware of have portrayed the Russian Civil War.[iv] So this movie, between its massive success and the lack of other films tackling the same subject matter, has had an outsized influence on how people in the English-speaking world see these events.

What follows are my notes on a re-watch of Dr Zhivago, focused on how it presents the history, sometimes comparing it to its source material (the novel of the same name by Boris Pasternak).

1: A flash-forward to… when?

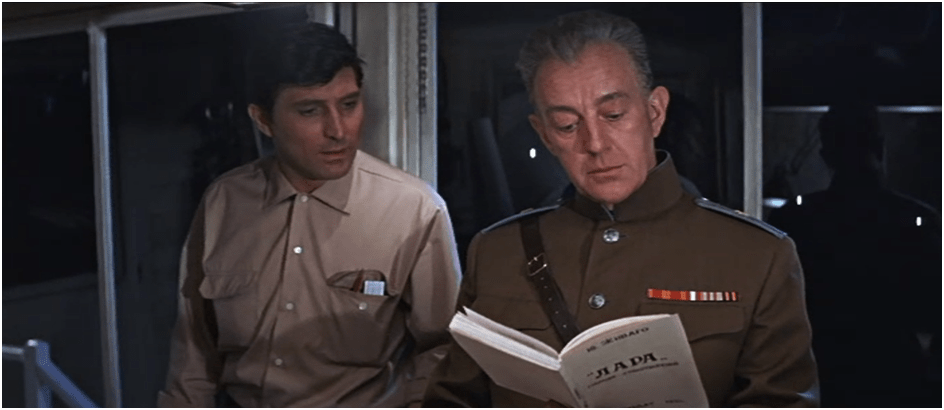

Dr Zhivago starts with Yevgraf (Alec Guinness), an apparatchik in the Soviet security forces, finding his orphaned and long-lost niece and telling her the story of her long-lost parents, Yuri Zhivago and Lara Antipova. This frames the narrative in a neat way as Yuri and Lara are the couple who are canoodling tragically on the movie’s poster.

This framing device works… unless you’re a nerd like me, in which case it will leave you wondering when exactly this flash-forward is supposed to be happening. [v]

The niece, Tanya (Rita Tushingham), looks around twenty and we will learn she was born in 1921. Maths would suggest we’re around the years of World War Two. But clues in the scene suggest otherwise.

The overall situation (a hydroelectric dam that seems to be fully operational plus also a horde of women and girls recruited from reformatories excavating rock with their bare hands) suggests we are in the period of shock industrialisation, the Five-Year Plans. And because Tanya is definitely not fourteen or fifteen, 1937 to early 1941 is our range. Right?

Maybe not. Other cues point to the 1950s. Yuri Zhivago’s poetry is going through a period of growing popularity.

‘Everyone seems to [admire him] – now,’ says the engineer.

Yevgraf replies acidly: ‘Well, we couldn’t admire him when we weren’t allowed to read him.’

Zhivago has been posthumously rehabilitated, meaning we are in a period of relative liberalisation. Relative prosperity, too. Referring to the era of Revolution and Civil War, Yevgraf does a ghoulish version of the Four Yorkshireman routine: ‘There were children in those days who lived off human flesh. Did you know that?’

This comparison between now and the bad old days only makes sense in the era after the death of Stalin in 1953, his denunciation in 1956, and the rehabilitation of vast numbers of people victimised by the Stalinist terror.

Only… Yevgraf’s niece is not in her mid 30s. And the dam appears to be called the Stalinskaya.

Where does that leave us?

If this scene is taking place in 1936-41, then the atmosphere is off. Soviet Union had just gone through a famine and massive campaign of repression in the early 1930s, followed by a terrible slaughter and mass imprisonment campaign that peaked in 1937. The engineer should be soiling his pants at the sight of Yevgraf, not complaining about shortages of machinery (though Tanya looks terrified at first).

Why have they made the film in this way? How serious a departure from history is it? It’s not outrageous so much as odd. It’s just strange to hear Yevgraf talking about how back in his day, there was cannibalism and certain poets were censored. Not like the era of plenty and pluralism known to historians as [checks notes] THE GREAT TERROR.

2: Central Asia

We flash back to somewhere in Central Asia, some time in late Imperial Russia. In a powerful contrast to the red stars and industrial trappings of the framing device, we see vast mountains and plains. Through the eyes of a little boy, we see the Orthodox priests, black-garbed like a murder of crows, who are presiding over his mother’s funeral. It is a moving scene: a musical crescendo, leaves blown from trees in a sudden gust of wind, nails hammered into the coffin. The little boy is then adopted by a kind family from Moscow who were friends of his mother.

Russia had colonies in Central Asia, and many Russian settlers still have descendants today in countries such as Kazakhstan. So the trappings of the Orthodox Church imposed on a Central Asian scene grounds us in the old Russia of the Tsars, imperial and obscurantist.

The little boy who is burying his mother is of course Yuri Zhivago (in this sequence played by Tarek Sharif, son of Omar). In the novel Yuri’s half-brother Yevgraf was born of a woman native to Central Asia. The movie, without ever saying so out loud, performs an interesting reversal: Yevgraf is the European and Yuri the ‘Eurasian.’ I don’t think fidelity to history was the primary concern here – David Lean just wanted to cast Omar Sharif. But having a lead actor who is from outside Europe is a good move from the point of view of history. Every third or fourth character you run into in the Russian Civil War turns out to be an Armenian from Persia, or a Baltic German who is obsessed with Mongolia, or one way or another has some colourful and complex national identity.

3: Moscow in 1913

(CW: SA)

My nerd rage at the chronological vagueness of the flash-forward is assuaged in the next section of the movie. Dialogue in a later scene (‘I have seen you. Four years ago, Christmas Eve’) places the action in this part of the movie in the winter of 1913-14.

Yuri is now an adult, studying medicine, writing poetry and preparing to marry his adopted sister Tonya (Geraldine Chaplin, incidentally the daughter of Charlie Chaplin). But he keeps running into this girl Lara (Julie Christie), who we know thanks to the framing device will go on to be the mother of Yuri’s child.

Lara, a seventeen-year-old student, is groomed, seduced and raped by a businessman who has leverage over her family, a predatory and perspicacious old monster named Komorovsky (Rod Steiger).

Lara brings this section of the movie to a close by shooting the sexual predator. But Komorovsky survives. Lara and her revolutionary boyfriend Antipov (Tom Courtenay) get married and move away to a distant village.

To film this and later parts of the movie, the crew built a couple of blocks of Moscow in a field in Spain and buried it under fake snow. It was well worth the effort. It looks the part. We will see this neighbourhood, including the huge townhouse of Yuri’s adopted family, going through sweeping changes over the course of the film.

The protest

It is on the main street of this Spanish Moscow that we see a workers’ demonstration crushed by the forces of the Tsarist autocracy.

The corresponding scene in the novel takes place during the 1905 Revolution. Viewers might assume wrongly that this is the infamous Bloody Sunday, or even that this scene represents the entire 1905 Revolution – watching this at age 15 or 16 I vaguely thought it was, but now I know that this massacre would not even qualify as a Bloody Wednesday on the scale of Tsarist Russia.

But the movie is not making a historical misstep here at all. Showing an event like this in 1913 makes sense. Several hundred strikers were massacred at the Lena goldfields in 1912, and in response there was a wave of strikes that only ended with the outbreak of the First World War. This would have involved protests and repression like we see here. The demonstrators perform the ‘Varshavianka’ and the ‘Internationale,’ both period-accurate. At the end of their demonstration, they march back the way they came, presumably sticking together until they reach the safety of a working-class district. But I’m not sure of the tactical rationale behind the dragoons attacking and dispersing them on their way back. I’d assume they would prefer to block the march from entering the affluent district.

It’s worth noting that we don’t see the inside of a factory, a railway yard or a slum. The focus is on how the demonstration turns Yuri’s head, sweeps him up in its romance, and how the state repression appals him. The focus throughout the movie is on how Yuri, who is part of a well-off family, reacts to the twists and turns of the revolution.

The Bolsheviks

On several occasions characters talk about the Bolsheviks. Antipov denies being a Bolshevik, but doesn’t tell us what party he’s in. ‘The Bolsheviks don’t like me and I don’t like them. They don’t know right from wrong.’

They are mentioned almost as if they were the only revolutionary party in the running. Komorovsky says to Yuri: ‘Oh, I disagree with Bolshevism. … But I can still admire Bolsheviks as men. Shall I tell you why? […] They may win.’

Before 1912, few knew who the Bolsheviks were. They were one faction of one leftist party (the Russian Social-Democratic and Labour Party). In 1912-14 the Bolsheviks grew rapidly. Antipov disliking them is a plausible glimpse of the leftist in-fighting and debates that went on. (The fact that he carries a pistol on a demonstration suggests he is a Socialist Revolutionary, a party with a terrorist legacy. I doubt he’s a Menshevik.)

Komarovsky’s remarks are not so plausible. The Bolsheviks weren’t a household name. Komorovsky would not have anticipated their victory and if he even knew who they were he wouldn’t expect Yuri to.

I can see why they name-dropped the Bolsheviks here in spite of the above points. The screenplay is introducing little things that are going to be big later. It’s not terrible – but it is wrong.

Tsarism

‘It’s the system, Lara,’ Antipov declares at one point, apropos of nothing. ‘People will be different after the revolution.’ The audience knows instantly that Antipov’s naivety will be cruelly exposed. But to me that’s a bit crude, a bit of a straw man.

All the same, we do get a glimpse of the system. This section paints an ugly picture of late Imperial Russia. A predatory, cynical capitalist, brutal state repression, even an orthodox priest dispensing free doses of sexual hypocrisy to Lara when she goes to the church for guidance.

But we do not see the squalid living conditions of the peasants or, bar the scene where Antipov is dropping leaflets outside a factory, the working or home lives of the urban proletariat. People show a remarkable ability to write many thousands of words and make many hours of cinema about revolutions without ever mentioning little things like the land question. You know, the number one factor motivating almost every modern revolution including this one.

Until next time…

I remember seeing this movie as a teenager and being swept along by it and I can really understand how, four decades earlier, millions were really enchanted by it in cinemas. All the more reason to interrogate how it presents the history. I’m approaching it now with a more analytical eye but I still appreciate and enjoy a lot of what I see here. So far, it’s not a bad job by the standards of a historical epic set in a country that few of the cast or crew would have ever set foot in.

But as I’ve made clear, there’s a bit of ‘The Tsar has been arrested! Lenin is in Moscow!’ to come. And the further we get, the more it goes off the rails.

In the next post we’ll look at how Dr Zhivago treats the First World War and the revolutions of 1917. For good and for bad, there’s a lot to talk about.

Revolution Under Siege archive

[i] ‘Lenin’s in Moscow’ can be shorthand for ‘Lenin has arrived in the capital city! No, not Moscow, the other capital, the one that doesn’t feature in this movie. Yes, St Petersburg.’ And ‘Civil war has started!’ is just Zhivago’s on-the-spot reaction. Some people in early 1917 characterised events the same way. But all that is a stretch. The average viewer will take it at face value.

[ii] Smele, Jonathan. The ‘Russian’ Civil Wars

[iii] What are my credentials for tackling this, and why does it interest me? Over the last few years I’ve written a lot about the Russian Civil War, and you can find the full book-length project here:

Revolution Under Siege

[iv] Soviet and Russian cinema is a different story. 1934’s Chapaev spawned a whole sub-genre of Civil War movies. I should mention the HBO TV movie Stalin (1992, dir Ivan Passer) which is overambitious and rushed but which does include a handful of fairly well-written scenes dealing with the Civil War.

[v] In the novel, this framing narrative takes place on the Eastern Front of World War Two. Yuri and Lara’s daughter is a boisterous young woman serving on the frontlines.