This post is about the anti-Semitic massacres carried out by the White Armies and the Ukrainian Rada forces during the Russian Civil War. It is the first part of the fourth series of Revolution Under Siege, my account of the Russian Civil War.

Go to Revolution Under Siege Archive

Avenger Street

The Russian Civil War sent fragments spinning in random directions, to lodge in unexpected places. Years later, a piece of shrapnel from the war hit the ground with lethal effect in Paris. On May 26th 1926 Shalom Schwartzbard, a refugee from Ukraine, approached a man on Rue Racine, drew a revolver and shot him multiple times.

‘When I saw him fall,’ said Schwartzbard later, ‘I knew that he had received five bullets. Then I emptied my revolver [into the body].’

He handed his revolver to a police officer and, in case there was any doubt, confessed on the spot: ‘I have killed a great assassin.’

More details filtered out to a shocked public. Schwartzbard had fought for the French Army in World War One. After the Russian Civil War, he had returned to his home country of Ukraine to discover that fifteen members of his immediate family had been murdered in a wave of anti-Semitic violence. The man murdered on that Paris street was Symon Petliura, the Ukrainian nationalist leader whose forces were responsible.

It is perhaps fitting that this blood was spilled on a French street. The French government was one of those which had by turns supported and spurned Petliura and his movement. France also supported other factions whose forces carried out pogroms, such as the White Armies and the Polish government.

Schwartzbard’s murder trial turned into a kind of tribunal about the pogroms of 1919. France itself was no stranger to anti-Semitism – this was only twenty years after Captain Alfred Dreyfus, an innocent Jewish officer in the French army, was branded as a spy. But such a horrific picture emerged of the 1919 pogroms that the French jury acquitted Schwartzbard in spite of his obvious guilt.

The carnage of 1919 has its echoes in the warzones of today. There is a street in Kyiv, Ukraine named after Petliura. And in Beersheba in southern Israel we can find Avenger Street, subtitled Shalom Schwartzbard Street. [i]

This chapter will attempt to trace that fragment back to its source, examining the storm of pogrom violence which raged across the former Russian Empire.

The White Pogroms

In 1919 the White armies of General Denikin marched on Moscow. Killings of Jews often followed the conquest of a town or the capture of a Red unit. This was the first time that districts where Jews lived in large numbers fell under the control of the White Armies, leading to a wave of pogroms in August and September. They ‘combined “normal” undisciplined looting with ideological anti-Semitism.’[ii]

One Red unit retreating from the Don Country fell into the hands of a partisan ‘Green’ band of Cossacks. At first the Cossacks only killed those who tried to escape, and mainly concerned themselves with robbing from or bartering with their captives. When an officer of the advancing Whites appeared, however, these ‘Greens’ joined the Whites instantly, and lined the prisoners up for inspection.

Eduard Dune remembered the massacre which followed:

Many of the Cossacks had drunk more wine than they should have, but even the [White] commandant, who was sober, took us in with a vacant, sarcastic glance. He began his tour of the ranks without a single word; he would stop silently, look us over, and move on. […]

“Yid?” he asked Aronshtam, the brother of the brigade commissar.

“I am a Jew!” he replied.

“Two steps forward. Right face-run!”

Aronshtam turned to the right, but he didn’t run. He moved forward a step and looked back. The officer wasn’t looking at him, he was going on to the next man.

The Cossacks maliciously cried, “Run, you mangy sheep!”

But he didn’t know where to run, there was a half circle of Cossacks in front of him, Cossacks with rifles pointed. He approached almost to their muzzles, and then fell backward from a shot at point-blank range.

Stunned by the image of Aronshtam’s death, I tried not to look at the next shootings of “Yids,” which included Russians as well as Jews. [iii]

The White officer wanted to single out and murder Jewish people – or sometimes merely those he suspected of being Jewish. And the Cossacks were willing participants. Why?

The officer and the Cossacks grew up in Tsarist Russia, where Jews were openly persecuted. The Tsar’s secret police wrote and published the notorious Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion, a book which purported to disclose the details of an alleged Jewish plot for world domination. Laws discriminated against them, and state-sponsored mobs from time to time waged brutal campaigns of arson, robbery, rape, assault and murder against them. These campaigns were known as pogroms. Naturally, this ethos of persecution permeated the upper classes and the army and seeped out through the whole society.

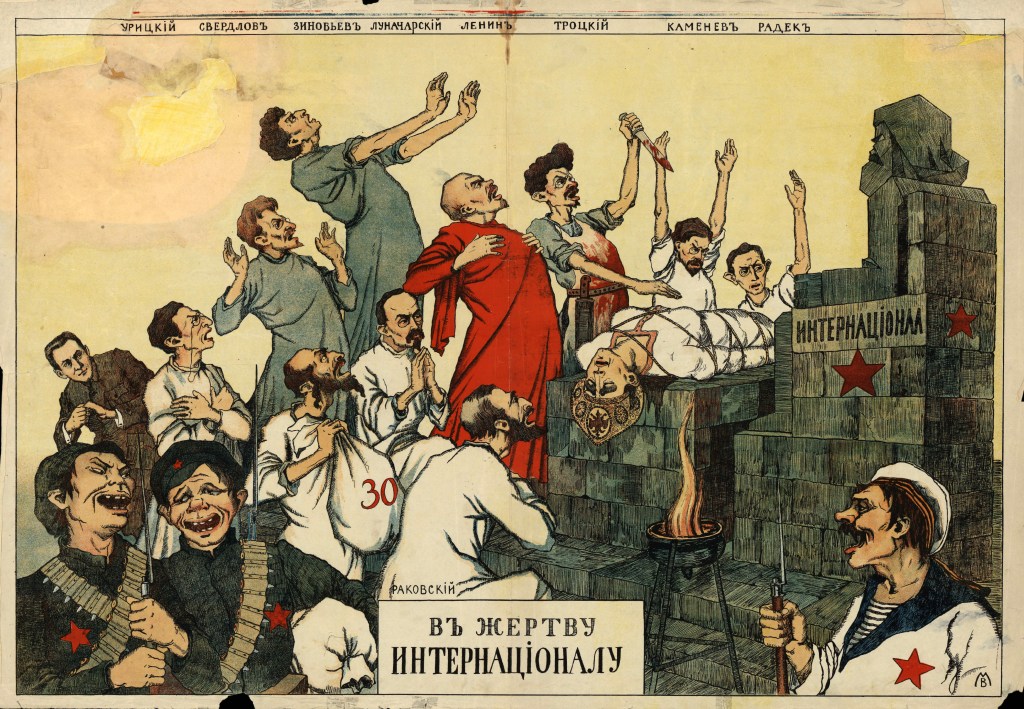

Beevor gives the impression that the Revolution, by empowering workers and poor people, thereby opened the floodgates for anti-Semitic violence. This stands reality on its head. Those who hated the Revolution shamelessly used anti-Semitism as a weapon against it. The Protocols circulated widely in the ranks of the White Armies; ‘Jew’ and ‘communist’ were practically synonyms in their propaganda; and they also published another forgery, the ‘Zunder Document,’ which was supposedly found on the body of a Red commissar – ‘evidence’ that the whole Revolution was a Jewish conspiracy.[iv] Famous White propaganda posters such as ‘Victims of the International’ and ‘Witness the Freedom in Sovdepiya’ were weighed down with anti-Semitic caricatures and tropes.

There was a spectrum of anti-Semitic delirium. On the extreme end was Baron Ungern-Sternberg, who believed he had a sixth sense which could identify Jews and who had an elaborate occult mythology to justify his desire to murder them all. On the more pragmatic end, White generals such as Budberg were not so unhinged. Still anti-Semitic assumptions were so much a part of their make-up that they took for granted the idea that ‘the Jews’ were behind the Revolution.[v]

In the early 20th Century, Jews were widely blamed for all the evils of life under capitalism and, conveniently, also for the revolutionary movements which developed in response to these evils. They were all-purpose scapegoats for modernity. For the reactionary officer who didn’t want to remove his head from the sand, it was far easier and more comforting to blame the Jews than to accept that the revolution was a mass movement with deep roots in Russian society.

The Soviet military commissar Trotsky was himself from a Jewish background, from a farm in South-West Ukraine. He answered the question of why Jews made up a ‘fairly high’ proportion of the Red leadership, although ‘far from constituting such a big percentage of the total as is maintained in White-Guard reports, leaflets and newspapers.’ He also noted that White officers not only hated the Jews, but imagined them to have superior talents.

Anti-semitism means not only hatred of the Jews but also cowardice in relation to them. Cowardice has big eyes, and it endows its enemy with extraordinary qualities which are not at all inherent in him. The socio-legal conditions of life of the Jews are quite sufficient to account for their role in the revolutionary movement. But it has certainly not been proved, nor can it be proved, that Jews are more talented than Great Russians or Ukrainians.[vi]

Denikin apparently issued several edicts against anti-Semitism. But they were ignored, and he didn’t try to enforce them.

The British chief rabbi counted ‘no less than 150 pogroms carried out by Denikin’s army,’ and the Red Cross reported that the ‘Retirement of Soviet troops signified for the territory left behind the beginning of a period of pogroms with all their horrors.’

Winston Churchill, the foremost advocate of intervention in Britain, was under pressure from his liberal coalition partners. Lloyd George urged him: ‘I wish you would make some enquiries about this treatment of the Jews by your friends.’

So Churchill made a half-hearted attempt to get Denikin to stop his men slaughtering Jewish people; ‘the Jews were powerful in England, he declared.’ Historian Clifford Kinvig remarks: ‘not the most altruistic expression of concern, it must be said.’

But General Denikin would not oblige. In fact, he formally refused to declare Jews equal before the law.[vii]

By mid-November 1919 Denikin’s advance had reached its limit. The retreat was orderly at first. But after the fall of Kharkiv to the Reds, panic set in. Baron Wrangel launched a tirade against Denikin. Denikin responded by accusing Wrangel of plotting a coup. Wrangel was fired and packed off to Constantinople. The Whites gave up most of Ukraine without offering resistance (a key exception was Crimea, which will be very important later). In Odessa another evacuation of White sympathisers took place, this one even more chaotic than the last. ‘Ships slowly listed under the weight of people clinging to the deckrails and scrambling aboard.’ The revolts in Denikin’s rear gathered pace.[viii]

The British general Holman spent the months of retreat jumping in aeroplanes to personally fly bombing missions against the advancing Reds. It must have been dispiriting that the flights kept getting shorter. Even after retreating to Ekaterinodar, his refrain did not change: ‘let’s take an aeroplane and a tank and bomb the blighters.’

General ‘bomb the blighters’ Holman, according to another officer, ‘is obsessed by the idea of wiping out the Jews everywhere and can talk of little else.’ He even asked a military chaplain why the Anglican church ‘did not start a crusade against them.’ Another Englishman, Commander Goldsmith, is quoted as saying that ‘a Russian Jew is quite the most loathsome type of humanity.’ [ix]

When so many powerful people in the Allied camp were themselves Anti-Semitic, it’s no wonder the Allies continued to support the Whites even though they murdered Jews.

The retreat saw a terrible wave of pogroms. The White Guards would sing: ‘Black Hussars! Save our Russia, beat the Jews. For they are the commissars!’ And they were as good as their word, once again inflicting terror on the Ukrainian towns and villages.

Kolchak’s forces in Siberia did not enter Jewish-majority areas, but still made their violent prejudices known, especially during retreats. They had killed 2,200 Jewish people in a pogrom just before they pulled out of Yekaterinburg on July 15th. Dragomirov, the White general presiding in Kyiv, allowed his forces to torment the Jews of that city for six days. [x]

Pogroms in Ukraine

From February 1917 through 1918, attacks on Jews throughout the former Tsarist empire were in general sporadic and small in scale. Nor did Petliura’s forces begin the massacres when they first took over large parts of Ukraine in late 1918. It was when the Petliura forces were defeated by the Red Army at the very end of 1918 and the start of 1919 and fled westward in demoralised fragments that they began attacking Jewish communities. These attacks carried on through 1919. The horrific atrocities of Ataman Grigoriev (See Chapter 17) constituted a major escalation.

The first large-scale pogroms were carried out by retreating Ukrainian Rada soldiers on December 31st 1918. The Proskurov Pogrom of February 1919 provides a vivid example of what a pogrom looked like. Rada forces under Ivan Samosenko entered the town of Proskurov (now Khmelnytskyi) and, under the slogan ‘Kill the Jews, and Save the Ukraine’, murdered 1,500 Jewish men, women and children in three or four hours, using sabres and bayonets. The pogrom was supposedly a reprisal for a failed Soviet uprising in the town.

Another hard-hit area was Chernobyl, where gangs under a warlord named Struck raided towns and boarded steam ships on the river Dnipro in order to carry out murders.

In the Brusilov/ Khodorkov area in mid-June 1919, 13-year-old Jack Adelman was woken in the middle of the night by gunfire. People he refers to as ‘bandits’ had seized the town.

My mother, sister and I quickly dressed and ran. My grandparents refused to leave. We joined hundreds of other Jews who quickly left town and walked or ran into the countryside. It soon got light and we saw several armed men on horseback come closer and closer. When they reached us, they ordered us back and lined us up near a sugar factory on the outskirts of the town. They separated the men from the women and children. I was thirteen years old, but very small and was left with the women and children. The men were driven back into town and locked up in a synagogue. This and adjacent buildings were set on fire. The men perished in the fire. One person survived. He was thirteen years old, but tall for his age. I never found out how he managed to survive.

The whole town burned down. Many people were killed, and more were wounded. One aunt of mine was badly wounded and died a few days later. Two of her daughters were wounded by swords but survived. I saw a teacher of mine sitting in the ditch off the road. I realized he was shot and killed while trying to hide in that ditch. I never really learned how many people died in this pogrom.

Around noon the bandits left after the entire town was destroyed. We headed toward the nearest railroad station, about twenty miles from our town. We finally came to Kiev a day or two later and there learned that my aunt was dead.

The dates suggest that the bandits were part of the Grigoriev revolt.

Adelman and his family experienced extreme poverty in Kyiv and then fled via Poland to the United States, where he would write the above account in a senior citizens’ writing group in the 1980s. He was one of millions turned into refugees by the violence.

‘The Ukraine Terror and the Jewish Peril,’ a contemporary pamphlet, contains numerous other graphic and disturbing accounts. Often the ordeal was drawn out over several days and involved a steady one-sided escalation – from robbery, the levying of collective ‘contributions,’ public humiliation and sexual assault to massacre. The survivors might again be extorted for ‘contributions.’[xi]

Pogroms were able to happen because the pogromists had the monopoly or near-monopoly on armed force. The pogromists had all the rifles, grenades, bayonets and sabres, and the victims were a helpless captive population.

Why Ukraine?

Jews made up 9% of Ukraine’s population. Because of historic persecution, they were concentrated in the cities and many were merchants and professionals. The natural antagonism between the farmer and the merchant was supplemented by national tensions and religious bigotry. Where the White officer assumed that Jews were traitors to Russia, Ukrainian nationalists tended to see them as agents of Russian imperialism. The Jews were general purpose, one-size-fits-all scapegoats.

Carr writes: ‘According to a Jewish writer, a member of the Rada called anti-Semitism at this time [1918] “our principal trump.”’ This suggests that at least some Ukrainian Nationalist leaders were happy to make political capital by fuelling anti-Jewish hatred.

Some historians defend Petliura today. His regime made some ‘efforts towards combating anti-Semitism within its lands’ and it is argued that he was ‘not culpable for events that were beyond the control of a weak and besieged government in a chaotic land.’ This is not a bad argument, but it must be extended to nearly all factions in the conflict. [xii]

A 2013 article from the Times of Israel follows a descendant of Shalom Schwartzbard who is not sure who to believe – her relatives for whom Petliura was a villain or modern Ukrainian scholars who are trying to rehabilitate him.

“Petliura was not anti-Jewish — but as a leader, he was responsible,” said [Anatoly] Podolsky, [Director of the Ukrainian Institute for Holocaust Studies] who cited recent research into a pogrom in Proskurov in February 1919 in which 1,500 Jews were killed. One of Petliura’s military chiefs was the pogrom’s leader; Petliura ordered him executed, Podolsky said. [xiii]

Israel and Ukraine today are members of the same broad US-led coalition. Attempts to reappraise the history and rehabilitate Petliura align with modern political agendas. But they obviously clash with other modern political agendas, namely the United States’ arming of Israel. We can resolve this clash by pointing out that, whatever they may say today, very few politicians in Western Europe or North America in 1919 cared about either Ukrainians or Jews.

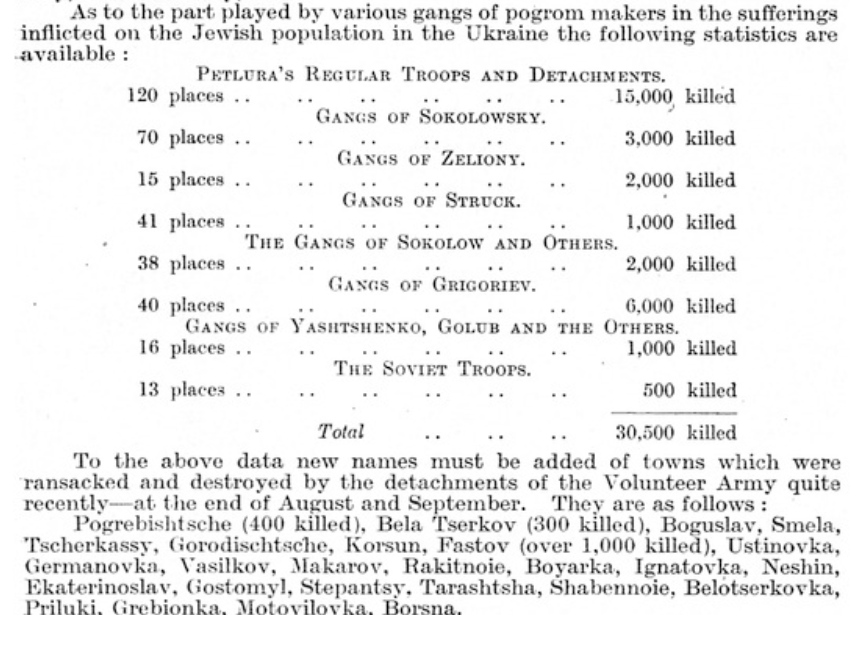

There is more ambiguity about the role of the Ukrainian anarchist Nestor Makhno. There are claims that he engaged in pogroms, though Makhno himself made a strong rebuttal.[xiv] Polish forces also carried out pogroms and, during the 1920 war with the Soviet Union, interned Jews en masse and discharged them from the army. There were also instances of Red units carrying out pogroms, especially in 1920 with Budennyi’s Red Cavalry in Poland but also earlier: in the pamphlet ‘The Ukraine Terror,’ we learn of bloody incidents in Rossava, February 11th to 15th 1919, and a couple of months later in Vasilkov. This was in a context where Red forces were newly mobilising in Ukraine and were still plagued by ‘partisanism’ and indiscipline.

The difference is that the Black and Red armies both ruthlessly punished those of their own soldiers who carried out pogroms, and this resulted in a much lower incidence. White officers responsible for pogroms were almost never punished.

Who were the worst offenders when it came to pogroms, the Ukrainain Rada or the White Armies?

Kinvig says it was Denikin and the Whites (p 232): ‘many, no doubt, [were killed] by partisan forces and bandit groups, but the majority, it seems, by Denikin’s armies’); Smele says it was probably Petliura and the Rada. ‘Most of these pogroms – and certainly the most brutal and extensive – occurred during the rule in those regions of the Directory of the UNR [the Rada] in 1918-19.’ (p 161)

Most pogroms were carried out by soldiers – soldiers who had received their training in the openly anti-Semitic institution that was the army of the Tsar. 15 million men passed through this army during World War One, and went on to fight for all sides in the Civil War. So whether it manifested in the White or in the Ukrainian Rada armies, or even amid the Reds or Anarchists, hatred of Jews was a legacy of Tsarist Russia. That said, the Red Army suppressed that legacy while the White Armies basked in it.

Conclusion

There were 1,500 pogroms in 1,300 localities across Ukraine and Galicia in 1918-1919. In all, somewhere between 50,000 and 200,000 lost their lives with another 200,000 ‘casualties and mutilations’ and millions forced into exile. Thousands were sexually assaulted and that some who served ‘in the local Soviets were even boiled alive (‘communist soup’).’ [xv]

If we compare these pogroms with the Holocaust twenty years later, we see some disturbing parallels. The two atrocities happened in the same regions and were visited on the same communities. There is a certain overlap between the White Guard, Baltic German and nationalist movements in Eastern Europe in 1918-19 and the Nazis and collaborators in the same region in World War Two. The White movement functioned as a greenhouse in which anti-Semitic ideas flourished which would later be employed by the Nazis.

On the other hand, the Holocaust killed millions whereas the victims in 1919 numbered in the low hundreds of thousands. The Holocaust was carried out not by locals (notwithstanding the participation of some) but by an occupying imperial power, Nazi Germany. Finally, the genocide of 1919 was carried out with primitive methods (often, literally, with fire and the sword) while the genocide of the 1940s was carried out with a developed industrial apparatus of death factories.

The pogroms of 1919 were certainly the worst massacre of Jews in modern times excluding the Holocaust, and they had both immediate and long-lasting impacts. The historian Budnitskii, quoted in Smele’s book (162), writes that ‘The experience of Civil War showed the majority of the Jewish population of the country that it could only feel secure under Soviet power,’ and in the 1920s Soviet Jews showed a very accelerated rate of assimilation. On the other side, the pogroms rebounded upon their perpetrators, causing moral rot and civil chaos within the White camp and hastening its defeat.

Go to Revolution Under Siege Archive

References

[i] Smele, p 163-4

[ii] Mawdsley, p 290

[iii] Dune, Eduard. Notes of a Red Guard, University of Illinois Press,1993. Eds Koenker, Diane and Smith, S.A. pp 163-164

[iv] Beevor, p 37. Palmer, James, The Bloody White Baron, Faber & Faber, 2009, p 97

[v] The Diary of General Budberg, entry for July 4th 1919. Accessed at militera.lib.ru

[vi] ‘The Red Army as seen by a White Guard’ in LD Trotsky, How the Revolution Armed, Volume 2: 1919. https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1919/military/ch20.htm

[vii] Kinvig, p 232

[viii] Smele, 136, Kinvig, 310

[ix] Kinvig, 307, 310, 232

[x] Beevor, p 391-2

[xi] ‘The Ukraine Terror and the Jewish Peril’, published in London, 1921 by the Federation of Ukrainian Jews. https://ufdc.ufl.edu/AA00007151/00001/images/0

‘Memories of a Ukrainian Pogrom’ by Jack Adelman, https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/memories-of-a-ukrainian-pogrom

[xii] Smele, 160-64; Carr, EH. The Bolshevik Revolution Volume 1, 1950, Pelican, 1969, p 306

[xiii] ‘Did Shalom Schwatsbard avenge the pogroms or kill the wrong man?’ Hillel Kuttler, timesofisrael.com, 19 Jan 2013. https://www.timesofisrael.com/did-shalom-schwartzbard-avenge-the-pogroms-or-kill-the-wrong-man/

[xiv] ‘The Makhnovschina and anti-Semitism,’ Nestor Makhno, 1927. https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/makhno-nestor/works/1927/11/anti-semitism.htm

[xv] Smith, SA, Russia in Revolution, p 188