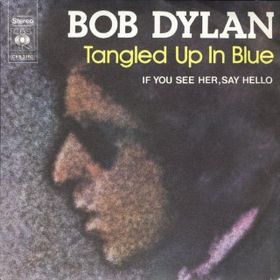

Tangled up in Blue (Bob Dylan, Blood on the Tracks, 1975)

The lyrics to this fine song get tangled up in apparent non-sequiturs, making you ask questions, making your imagination work overtime. The whole story is short on details, but we feel like the narrator has told us more than he really has. The lyrics are heavy with suggestion like branches bent under the weight of fruit. Dylan makes us work to extract the meaning, and we are grateful for it.

For example:

But he started in to dealing with slaves/ And something inside of him died/ She had to sell everything she owned and froze up inside/ And by the time the bottom fell out I became withdrawn…

What does that mean? How does one thing lead to the next? Things are skated over in vague terms, as if the narrator is wary of the legal implications, doesn’t want to open a can of worms, or just doesn’t want to think about it all.

It’s not just the usual obscurity and symbolism of Bob Dylan lyrics. It feels as if someone drunk and a little maddened by hardships, charismatic in his way, has sat down beside you on the bus and begun to tell you their history with a red-haired woman you’ve never met. Or maybe you’re overhearing one half of a stranger’s phone conversation – you missed the start, you’ll miss the end and you’re only hearing the answers, not the questions.

I read that Dylan tried, in writing this song, to dispense with any sense of time entirely. That was the first impression I got – that the timeline was all jumbled up, that there might even be multiple narrators, multiple situations connected only by theme. But by my 10th or 20th compulsive listen, it was starting to come together.

The song has a consistent thread. It tells the story of a relationship between the narrator and a woman. They get separated, but they drift back together, get separated again, but maybe they’ll be reunited… Is her nickname Blue? Does she have blue eyes? Or is it a reference to Joni Mitchell?

She was married; he ‘helped her out of a jam, I guess/ But I used a little too much force.’ The narrator probably didn’t kill the husband but he must have beat him up or something. They headed off on a journey together but ‘split up on a dark sad night, both agreeing it was best.’ The narrator is lying; he was devastated by the separation, but he doesn’t tell us that directly, or why they split up.

They meet again in Louisiana years later. She is working at a strip club and reading Italian Renaissance poetry; she lives in a basement with the narrator and another man, the one who ‘started in to dealing with slaves,’ whatever that means.

On rare moments we get detail. The ‘dark sad night’ when they split up is seared into the narrator’s memory and when he tells us about it he is not summing up and skipping over, but quoting her in real time. ‘I heard her say over my shoulder/ ‘We’ll meet again someday on the avenue.’

Then we skip ahead years and thousands of miles, until the narrator and the woman who ‘never escaped his mind’ are by chance reunited. We get verse after verse, describing the reunion almost iin real time.

He’s not an expressive or emotive guy – ‘you look like the silent type;’ ‘I muttered something underneath my breath.’ But we can tell how he’s feeling. He hints and summarises and skims over most of his life but then gets drawn into fine detail when he’s talking about her. The specifics he gives us are not the ones lawyers or cops or journalists might want to know. They are the things that matter to him.

I’ve had my ups and downs with Bob Dylan. He was as immaculately frightful as any surreal, pitiful denizen of Desolation Row when he accosted me in a pool hall impersonating Jack Kerouac and tried to sell me a Chrysler. But I’ve listened to his 2017 Nobel Prize lecture through from start to finish, multiple times. It’s a pleasure.

I think in that speech Dylan threw a sidelight on ‘Tangled up in Blue’ when he talked about Homer’s Odyssey and how he relates to it:

In a lot of ways, some of these same things have happened to you. You too have had drugs dropped into your wine. You too have shared a bed with the wrong woman. You too have been spellbound by magical voices, sweet voices with strange melodies. You too have come so far and have been so far blown back. And you’ve had close calls as well. You have angered people you should not have. And you too have rambled this country all around. And you’ve also felt that ill wind, the one that blows you no good.

The parallel lies not at all in the specifics – but in how he can find and bring out the epic and the immortal in the mundane, how he elevates his narrator to the status of a hero.