Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs and the 1960s

[This is another essay I wrote around 2014, migrated over from my old blog…]

In 1965 Bob Dylan played a new song of his to Phil Ochs (according to different accounts, it was either “Sooner or later” or “Can you please crawl out your window”). The two were travelling in a taxi when Ochs gave his opinion of the song: “It’s OK, but it’s not going to be a hit.” Dylan told the driver to stop and said, “Get out, Ochs. You’re not a folk singer. You’re just a journalist.”[1] Relations between the two were not usually hostile, but the incident was a manifestation of inherent tensions and conflicts within the folk revival and the radical movements of the 1960s.

These two very different men, at one stage described as the King (Dylan) and President (Ochs) of the topical protest song,[2] reflected and were affected by different aspects of the culture and politics of the 1960s. With a focus on Dylan and Ochs we will firstly explore the different aspects of the folk revival of the early 1960s, in particular the conflict between image and reality. Then we will look at how Dylan, like many activists and artists in the 1960s, substituted radical form for radical content. Finally, we will describe how Ochs reacted to the political defeats of the left in the late 1960s. In this the differences and to some extent the conflicts between the different aspects of the movement that they represented were clear.

Different aspects of 1960s culture and politics were immediately audible in the early music and lyrics of the two musicians. Ochs was journalistic, satirical, overflowing with facts and information while Dylan conveyed images and feelings. Ochs reacted to the Cuban Missile Crisis with a mocking exposure of US politics:

…some Republicans was a-goin’ insane

(And they still are).

They said our plan was just too mild, Spare the rod and spoil the child,

Let’s sink Cuba into the sea,

And give ’em back democracy,

Under the water!

“Talkin’ Cuban Crisis”, I Ain’t Marching Anymore, Elektra (1964)

This was a folk song in the tradition of Guthrie’s “Talking Sailor” and “Talkin’ Dust Bowl Blues”, musically simple and lyrically conversational or journalistic. While Dylan too wrote some “Talkin’” songs, he reacted to the Cuban Missile Crisis with a song that stood in a different part of the folk tradition:

I saw a newborn baby with wild wolves all around it

I saw a highway of diamonds with nobody on it

I saw a black branch with blood that kept drippin’[…]

“A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, Columbia (1962)

This was a metaphorical prophecy, standing closer to eerie old ballads like “Nottamun Town” and shading into later 1960s psychedilia rather than to Ochs’ style of sassy, ironic, witty satire. A similar pattern is repeated with the Vietnam War. Even in later songs that were more metaphorical and image-based, Ochs remained specific and clear in his critiques:

Blow them from the forest and burn them from your sight

Tie their hands behind their back and question through the night

But when the firing squad is ready they’ll be spitting where they stand

At the white boots marching in a yellow land

“White Boots Marching in a Yellow Land”, Tape From California, A&M, (1968)

Dylan never directly referenced the Vietnam War, let alone any specific aspect of it, in his songs:

How many times must the cannon balls fly

Before they are forever banned?

“Blowin’ In the Wind”, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, Columbia (1963)

The King of the Philistines his soldiers to save

Puts jawbones on their tombstones and flatters their graves

Puts the pied pipers in prison and fattens the slaves

And sends them out to the jungle.

“Tombstone Blues”, Highway 61 Revisited, Columbia (1965)

By the time he released “Tombstone Blues”, of course, Dylan had somewhat moved away from traditional folk patterns and was more and more concerned with word-painting metaphorical landscapes as a means of satire along with increasing rock elements. However, a tendency away from the specific and towards the general was inherent in the folk revival from the start, and particularly in the tendencies represented by Bob Dylan as opposed to Phil Ochs.

“Masters of War”, for instance, in Ochs’ hands might have been a thorough and witty exposure of the military-industrial complex; in Dylan’s hands it was a simple but extremely heartfelt and bitter condemnation of war profiteers – “I hope that you die” is a line that was so intense that Joan Baez, when covering the song, would not sing it.[3] But Dylan, when he sang it, seemed to mean it. While Greil Marcus sees “Masters of War” as too simplistic to do Dylan’s talents justice,[4] the song is in fact characteristic of Dylan in that it substitutes emotion and strong, simple images for argument.

By comparison, Ochs represented those who were more concerned with information and argument. Compare Guthrie’s “The biggest thing that man has ever done” with Ochs’ “I Ain’t Marching Anymore”: in both the singer takes on an immortal persona and describes a journey through history. Guthrie is the spirit of the working-man who “fought a million battles and I never lost a-one” and will now “kick [Hitler] in the panzers and put ’im on the run.”[5] Ochs is the American soldier who has fought in every American war but after every experience of cruelty, injustice and dishonesty, “I knew that I was learning/ That I ain’t marching anymore”. Each song has a wealth of historical detail backing up a clear political statement.

“I Ain’t Marching Anymore” was Ochs’ most successful song, remembered as “the anthem” of the anti-war movement. Ochs playing it in public was enough to provoke a spate of draft-card burnings.[6] Its lyrics were incorrectly reported by FBI agents. As a witness at the trial of the Chicago Eight, Ochs was forced to recite the lyrics word-for-word to the judge and jury.[7] This song was no crude attempt to transplant the spirit of the 1930s or 1940s into the 1960s; it was an extremely successful song that inspired young protestors and alarmed their opponents.

While Ochs was heavily influenced by Guthrie’s form and content, Dylan was far more interested in Guthrie’s image. After listening to Guthrie’s “Ballad of Tom Joad” repeatedly and obsessively and reading his autobiography Bound for Glory, Dylan left Minneapolis in December 1960, hitch-hiking east to find Guthrie. He dressed and spoke like Guthrie, invented various hobo back-stories for himself, and imitated Guthrie on his early album covers.[8]

The attraction of Guthrie was the attraction of folk generally for middle-class young people like Dylan and Ochs. Cantwell explores this vital aspect of the folk revival, which he sees as “a form of social theatre” in which middle-class young people idolized and imitated the proletarian, rural and demotic folk singer. Hero-worship of rebel figures like Brando and Dean earlier in life gave way to an embrace of figures like Guthrie and Leadbelly, hobo rebels who were unlearned but had bitter life experience.[9] In hair and clothes 1960s radicals sought “to break with how successful people presented themselves in ‘straight’ society”[10]. Robes and flowers came later; the folk period was characterised by second-hand clothes associated with manual labour.

Dylan’s advice in “Subterranean Homesick Blues”, “don’t follow leaders”,[11] might have been very popular but he never sang anything like “don’t follow icons.” Ochs too understood the power of the icon in the contemporary US when in 1970 he joked (or perhaps seriously suggested) that “if there’s any hope for a revolution in America, it lies in getting Elvis Presley to become Che Guevara.”[12]

Many 1960s activists believed that radical politics must be matched by radical means of representation. Students for a Democratic Society preferred “a kind of emotional and moral plain-speaking” to political theory,[13] and the folk revival which spoke lyrically in a proletarian voice and musically with great simplicity and a minimum of instruments. Though highly-educated, Yippies like Rubin and Hoffman thought they could only communicate their message through strong images and rhetoric. They revelled in state repression and police brutality, spoke in a “hip patois” punctuated with the inarticulate words “you know”, and made poetic statements such as “We demand the politics of ecstasy!” instead of concrete demands and arguments.[14] In embracing the image, therefore, Dylan was, in the context of the 1960s, making a kind of political statement, and was in tune with many political activists of the day.

Lasch believes that this emphasis on the image “imprisoned the left in a politics of theatre, of style without substance […] which it should have been the purpose of the left to unmask.” Farber argues that the Yippies’ emphasis on “facile slogans instead of careful explanation” meant that they “gave most Americans little chance to understand them.”[15] Ochs, though helping to found the Yippies, considered the idea of a “freak counterculture” to be “disastrous.” What was needed was “an organic connection to the working class.”[16] Radicalism in form and radicalism in content were two connected but at times antagonistic phenomena in the 1960s.

Even when Dylan was writing “protest” songs, their message was never clear. The line “How many roads must a man walk down/ Before you can call him a man?”[17] is a reference to the civil rights marches, but taken out of context it could just as easily be a reflection on maturity and coming of age, with metaphorical roads representing human experience. Dylan’s 1964 song “My Back Pages” seemed outright to disown many of his former beliefs, though he is characteristically unspecific here about what beliefs he is rejecting. He suggests that in even trying to define and express explicit politics “I would become my enemy/ In the instant that I preach.”[18] Dylan was not just embracing new forms of expression; he was identifying explicit and concrete means of representation and argument as inherently corrupt.

Generally over the next few years Dylan expressed politics only in terms that were general, surrealist and metaphorical. Employers “say sing while you slave and I just get bored”; Jack the Ripper “sits at the head of the chamber of commerce”. Alongside these metaphors there is a message of fatalism; Dylan says he wants to help the listener to “ease the pain/ of your useless and pointless knowledge.”[19] Joan Baez claimed that Dylan “ends up saying there is not a goddamned thing you can do about [social problems], so screw it.”[20] Dylan didn’t “need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows”; he gave the impression that he simply knew and understood the world instinctively and had no need for science or expert opinion. Meanwhile, there was nothing to do but “Look out, kid”; the best you can hope for is to “Keep a clean nose, put on some plain clothes”[21] and escape capture by the “agents”, “superhuman crew” and “insurance men” of Desolation Row.[22] Later Dylan was to encourage listeners to seek redemption in religion; before he turned to religion he pointed instead toward redemption in an image of street-wisdom, a “subterranean” lifestyle and an avoidance of futile conflict with the authorities.

Other lyrical subject matter included non-political romantic songs and evocations of a “subterranean” freak lifestyle. The most striking feature of Dylan’s mid-1960s material, however, was his increasing number of songs in the second person which were harsh, bitter personal judgements:

[…] you know as well as me

You’d rather see me paralyzed

Why don’t you just come out once

And scream it“Positively 4th Street” (1965) Single, Columbia

Now you don’t talk so loud

Now you don’t seem so proud

About having to be scrounging your next meal

“Like a Rolling Stone” (1965) Single, Columbia

Well you walk into the room

Like a camel and then you frown

You put your eyes in your pocket and your nose on the ground

There oughta be a law against you comin’ around

You should be made to wear earphones

“Ballad of a Thin Man” (1964), Highway 61 Revisited, Columbia

Practically everyone Dylan knew from 4th Street in Greenwich Village and 4th Street in Minneapolis suspected that “Positively 4th Street” might be about them.[23] They need not have worried because these songs were primarily about Dylan himself. Ochs remembers how Dylan used to engage in verbal battles on nights out: it was “very clever, witty, barbed and very stimulating, too. But you really had to be on your toes. You’d walk into a threshing machine if you were just a regular guy, naive and open, you’d be ripped to pieces.”[24] Dylan was presenting himself as a kind of witch-hunter of phonies and bourgeois intruders who were, like the Thin Man, more comfortable discussing “lepers and crooks” with “great lawyers” and “professors” than they were mixing in Dylan’s culturally non-conformist milieu.[25]

It’s worth pointing out that in singing these songs Dylan had no qualms that he might tell any “lies that life is black and white” or become his own worst enemy “in the instant” that he preaches. Dylan’s judgemental songs are performances of his own streetwise image as well as portraits of uncool features for listeners to avoid unless they too wanted to be “ripped apart” by Dylan.

Music producer Paul Rothchild claimed that Ochs’ commitment to political causes was a cynical ploy along the same lines as this image-obsessed politics.[26] However, by all other accounts it is clear that Ochs’ commitment was genuine. He was the only musician who gave his word that he would come to the Chicago 1968 protests no matter what.[27] He would frequently turn down commercial gigs in favour of playing for free at political benefit gigs.[28] Abbie Hoffman remembers that “Phil never turned down anybody no matter what size the [political] group.”[29]

Ochs was, like the narrator of “The Biggest Thing the World had Ever Done” or “I Ain’t Marching Anymore”, a witness to more than his share of history. He was at the Newport folk festivals, the Berkeley Free Speech Movement and the first anti-war teach-in; he helped organise the Chicago ’68 protests; the “War is Over” rallies and “An Evening with Salvador Allende” were his brainchild; he visited Robert Kennedy in the White House and brought tears to his eyes singing “Crucifixion”; he was active in Mississippi when the bodies of three murdered civil rights activists were found. A great deal of Ochs’ person and career were deeply invested in the radical politics of his day.

At the Newport Folk Festival of 1966 Dylan performed songs with a backing rock band and an electric guitar, provoking outrage from many sections of the crowd.[30] During a tour of England he was called “Judas” by an audience member.[31] This was another manifestation of the inherent tensions and conflicts within radical politics and culture in the period. In the eyes of many on the folk scene, the modest, “authentic” and political folk genre was losing the prominent voice of Dylan to the corporate, egotistical, corrupted, apolitical world of rock.[32] Ochs believed that those who booed were engaging in “a most vulgar display of unthinking mob censorship. Meanwhile, life went on around them.”[33] Despite their differences in terms of content and form, Ochs in this period never abused Dylan, calling Highway 61 Revisited “the most important and revolutionary album ever made.”[34]

A large part of Ochs’ defence of Dylan must have been his own growing desire to try new musical styles. This resulted in his 1967 album Pleasures of the Harbor which was more poetic than political, incorporating orchestral arrangements rather than a simple guitar. The album received negative reviews but Ochs’ desire to find a new niche reflected changes that were taking place in the music business. Rothchild explains that though Ochs had been at home in “the pre-Beatle, pure folk era”, his producers were not convinced that he “was going to crack the pop world. He had the wrong image, the wrong voice” and his lyrics were not “relationship introspective.” The music business was no longer interested in folk, especially political folk with lyrics “of the intellect” rather than sex.[35] This shift was like a forewarning of even more significant changes afoot in politics.

Former SDS leader Tom Hayden believes that there were, speaking very generally, two main halves to the 1960s from a radical point of view. The first half was characterised by innocence and optimism, with a basic belief in the possibility of the redemption of the American dream.[36] The second “half” represented reality reasserting itself; a “clarification of where we really stood.”[37] This basic schema helps us to understand the waning of the civil rights movement and the rise of the Black Panthers; the collapse of SDS and the activity of “urban guerrillas”; overall, the change from optimism to either resignation or a more determined and dangerous form of struggle.

For Dylan the Kennedy assassination, race riots and the Vietnam War “transformed his attitude from one of wanting a moral reform and the cleansing of his society to one of despairing that this society was reformable at all” as early as 1964.[38] There was obviously no “clean break” at which the civil rights movement ended and the Black Panthers began, and Malcolm X had already raised similar ideas years before his death in 1965. Despite these ambiguities and others, we can say with confidence that the key events which contributed most to the demoralisation of activists occurred in 1968.

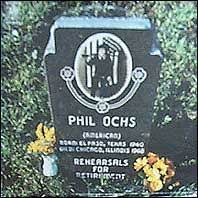

1968 in the US saw the assassination of Martin Luther King and the most widespread ghetto riots yet; the murder of Robert Kennedy; the repression of the Columbia University occupation; the Chicago Democratic National Convention protests; the strong vote for the ultra-conservative Wallace; and finally the victory of Republicans Nixon and Agnew in November.[39] Ochs was so closely integrated with the radical movements that to understand the significance of this year we need only look at the cover of his 1969 album “Rehearsals for Retirement”. It shows a gravestone which reads:

PHIL OCHS

(AMERICAN)

BORN EL PASO, TEXAS, 1940

DIED CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, 1968[40]

The album documented the changes that had taken place in that year in poetic, metaphorical terms:

I spied a fair young maiden and a flame was in her eyes

And on her face lay the steel blue skies […]

I’ll go back to the city where I can be alone

And tell my friends she lies in stone

In Lincoln Park the dark was turning

“William Butler Yeats Visits Lincoln Park and Escapes Unscathed” (1969) Rehearsals for Retirement, A&M

This expressed Ochs’ belief about Chicago that “something very extraordinary died there, which was America.”[41] Here idealized as a woman, the news Ochs brings back to Los Angeles is that illusions in a liberal, democratic USA are dead. Other songs illustrated this more violently:

And they’ll coach you in the classroom that it cannot happen here

But it has happened here […]

It’s the dawn of another age […]

We were born in a revolution and we died in a wasted war It’s gone that way before

“Another Age” (1969), Rehearsals for Retirement, A&M

Ochs expressed what this meant to him personally with the words “My life is now a death to me.”[42]

Ochs suffered from a long period of reduced output of songs and wild bouts of drinking and violent behaviour. The sudden, near-fatal attack on Ochs on a beach in Tanzania in 1973 caused his further deterioration. It is tempting to emphasize his father’s mental health problems and draw parallels with Ochs’ behaviour. However, we cannot separate Ochs’ mental health from the history and politics in which he had invested so much of himself, any more than we can separate his father’s mental health from his experiences in the Second World War.[43] The attack in Dar-Es-Salaam was simply a personal version of the kind of horrific and apparently meaningless event that had come to characterise the political world Ochs inhabited.

It is an indication of his personal deterioration that he did not learn of the September 11 1973 coup in Chile until December. Ochs had visited Chile and made friends with fellow folk singer Victor Jara, who was tortured and killed along with thousands of others after the counter-revolutionary military coup. Ochs later confessed, “When that happened I said ‘All right, that’s the end of Phil Ochs.’”[44] Despite this he set about immediately and tirelessly organising a huge benefit gig, “An Evening with Salvador Allende”, which he managed to secure Dylan’s presence at by reciting to him the late Allende’s inauguration speech in full, from memory.[45]

He swung between intense periods of political activity, self-destructive idle depression and absurd business ventures until in 1975 he began to claim that Phil Ochs had been murdered by “John Butler Train”. For an individual who had always set so much store in icons and whose ambition it was to become one, and for a representative of a genre defined as “social theatre” and a movement that had invested so heavily in icons, images and theatrics, it is significant that the nadir of Ochs’ decline was his long, violent performance as John Train. A brief recovery preceded his suicide in April 1976.

The last sixteen years of Ochs’ 36-year life could be read as a history of the rise and fall of the radical movements of the “long 1960s.” As if to dramatise the death of the movement, Ochs as “Train” was a violent, cynical, misogynistic wreck. His drunken conspiracy-theory rants were like a dark, twisted parody of Ochs’ witty on-stage patter.[46] The “Train” stood for the boxcar-riding hoboes the young activists had once idolized[47] and so Train’s character seemed to be a dramatisation also of the fact that the working class, in whose image the folk revivalists had tried to construct themselves, had by and large not been won over by the radicals of the 1960s.[48] Ochs’ deterioration and suicide were a reflection of history and politics at least as much as they were personal.

A Melody Maker journalist was perceptive in describing Dylan and Ochs as the King and President, respectively, of the “topical song.”[49] If Dylan was a leader his style of leadership was ceremonial and symbolic like that of a modern monarch. From the start he neglected direct, specific protest lyrics in favour of radicalism in form and image. His travelling-hobo clothing and voice conveyed a radical message in and of themselves but this soon gave way to a rock-star image as his music turned increasingly toward experimentation, and his lyrics toward personal problems, definitions of coolness and fatalistic metaphorical depictions of the world around him. He rarely advised his listeners to take any action or condemned anything specific – instead he created in himself an ultra-cool radical image and icon capable of knowing and expressing intuitively what the world was like and who was cool and who was not. Accordingly the changes of the late 1960s did not detract from him significantly since he was invested in a politically uncommitted self-image rather than in politics itself.

Monarchs generally rule for life while Presidents only enjoy a limited term. In the US they are executive and military leaders. It is a fitting image for Ochs, who in his lyrics generally made it clear and specific what he stood for and what he opposed. His commitment to active politics was enthusiastic and generous. Ochs had been at home in Hayden’s optimistic and active “half” of the 1960s. With the onset of pessimism, retreat and demoralisation, especially after 1968, he characterised himself and the movement as powerful, but out of their element: “A whale is on the beach/ It’s dying.”[50]

Ochs, in his “Train” persona, believed that Dylan “in a cowardly fashion hid behind images – after his third album”. Dylan’s albums between 1967 and 1974 were widely perceived as weak[51] and “Train” imagined accosting Dylan with the words, “Listen, asshole, I can kill you as soon as look at you. You were Shakespeare at twenty-five, and now you’re dog shit.” This cannot be sincere because Ochs, along with most critics, was hugely impressed by 1975’s Blood on the Tracks.[52] Meanwhile Ochs’ defence of Dylan after Newport 1966 suggests that this resentment was not rooted in envy of Dylan’s success or talents. It seems instead that this was another manifestation of the inherent conflicts in the culture and politics of the 1960s. Ochs’ resentment stemmed from the fact that Dylan had at an early stage abandoned the political struggle to which Ochs had sacrificed his career, his sanity and most of his adult life. Rather than seeking social change Dylan, like the hippie movement, sought personal redemption; like the folk revival, he constructed an icon; like the Yippies and SDS he preferred intuition to analysis and images to politics.

Bibliography

Books

- Boucher, David and Browning, Gary (eds), The Political Art of Bob Dylan, Imprint Academic, 2009

- Cantwell, Robert, When We Were Good: The Folk Revival, Harvard University Press 1996

- Eliot, Marc, Phil Ochs: Death of a Rebel, Omnibus, 1990 (1978)

- Farber, David, The Age of Great Dreams: America in the 1960s, Hill & Wang, 1994

- Farber, David, Chicago ’68, University of Chicago Press, 1988

- Gill, Andy, The Stories Behind the Songs, 1962-1969, Carlton Books, 2011 (1998)

- Isserman, Maurice and Kazin, Michael, America Divided: The Civil War of the 1960s, New York, Oxford University Press, 2008

- Marcus, Greil, Bob Dylan by Greil Marcus, Writings 1968-2010, Faber & Faber, 2010

Albums

Bob Dylan:

- Bob Dylan, Columbia, 1962

- The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, Columbia, 1963

- The Times They are a-Changin’, Columbia, 1964

- Another Side of Bob Dylan, Columbia, 1964

- Bringing it All Back Home, Columbia, 1965

- Highway 61 Revisited, Columbia, 1965

- Blonde on Blonde, Columbia, 1966

- John Wesley Harding, Columbia, 1967

- Nashville Skyline, Columbia, 1969

- Blood on the Tracks, Columbia, 1975

- The Basement Tapes¸ Columbia, 1975

Phil Ochs:

- All the News That’s Fit to Sing, Elektra, 1963

- I Ain’t Marching Anymore, Elektra, 1964

- Pleasures of the Harbor¸ A&M, 1967

- Tape From California, A&M, 1968

- Rehearsals for Retirement, A&M, 1969

- Greatest Hits, A&M, 1970

Film

- Bowser, Kenneth, Phil Ochs: There But For Fortune, First Run Features, PBS American Masters, 2012

[1] Andy Gill, The Stories Behind the Songs 1962-1969, Carlton Books (1998, 2011), 128

[2] Marc Eliot, Phil Ochs: Death of a Rebel (1978), Omnibus (1990), 109

[3] Greil Marcus, Bob Dylan by Greil Marcus: Writings 1968-1010, Faber & Faber (2010), 410-12

[4] Marcus, 412

[5] Woody Guthrie, “The Biggest Thing That Man Has Ever Done”, The Columbia River Collection Smithsonian Folkways, (1941, 1988); Phil Ochs, “I Ain’t Marching Anymore”, I Ain’t Marching Anymore, Elektra (1965)

[6] Kenneth Bowser (writer and director), Phil Ochs: There But For Fortune, First Run Features (2012); 00:20:18, 00:46:30

[7] Eliot, 181

[8] Gill, 17-18, 32

[9] Robert Cantwell, When We Were Good: The Folk Revival, Harvard University Press (1996), 2, 17, 347

[10] Isserman and Kazin, America Divided: The Civil War of the 1960s, Oxford University Press (2008), 155

[11] Bob Dylan, “Subterranean Homesick Blues”, in Bringing it All Back Home, Columbia, (1965)

[12] Eliot, 97

[13] Isserman & Kazin, 180

[14] David Farber, Chicago ’68, University of Chicago Press (1988), 7, 20-23

[15] Christopher Lasch, The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations, Abacus (1979), 81-82; Farber, Chicago, 225, 244-5

[16] Eliot, 163-4

[17] “Blowing in the Wind”

[18] Bob Dylan, “My Back Pages”, Another Side of Bob Dylan, Columbia (1964)

[19] Bob Dylan, “Maggie’s Farm”, Bringing it All Back Home, Columbia (1965); “Tombstone Blues”, Highway 61 Revisited, (1965)

[20] Gill, 94

[21] “Subterranean Homesick Blues”

[22] Bob Dylan, “Desolation Row”, Highway 61 Revisited, Columbia (1965)

[23] Gill, 126-7

[24] Gill, 127

[25] “Ballad of a Thin Man”

[26] Eliot, 76

[27] Farber, Chicago ‘68, 26

[28] Bowser, 00:09:04

[29] Bowser, 00.09:10

[30] Gill, 111

[31] Michael Jones, in The Political Art of Bob Dylan, ed. Boucher & Browning, Imprint Academic (2009), 75-80

[32] Jones, 82

[33] Eliot, 96

[34] Gill, 113

[35] Eliot, 119

[36] Bowser, 00:17:37

[37] Bowser, 00:38:05

[38] The Political Art of Bob Dylan, 38

[39] Isserman & Kazin, 319

[40] Phil Ochs, Rehearsals for Retirement, A&M (1969)

[41] “William Butler Yeats Visits Lincoln Park and Escapes Unscathed”, live performance in Vancouver, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VWEBlZ7C_lE&playnext=1&list=PLD33BBF4B10862910&feature=results_video, accessed 3/3/2013, 17:14

[42] Phil Ochs, “My Life”, Rehearsals for Retirement, A&M (1969)

[43] Eliot, 12

[44] Eliot, 256

[45] Bowser, 00:58:30 – 01:06:00

[46] Eliot, x-xv

[47] Eliot, 262. The following comes from the liner notes of a planned album written in 1975: “John stands for Kennedy, Butler stands for Yeats, Train stands for hobos at the missed silver gates.”

[48] Isserman & Kazin, 280

[49] Eliot, 109

[50] Phil Ochs, “No More Songs”, Greatest Hits, A&M, 1970

[51] Marcus, 7-27

[52] Eliot, 243, 255