This post tells how the White Guards fled South Russia in a state of complete chaos, but survived and established a new base in Crimea. This is Series 4, part 3 of Revolution Under Siege, an account of the Russian Civil War.

A Red soldier named Eduard Dune was captured during Denikin’s advance on Moscow. Among other terrible ordeals in captivity, he succumbed to typhus. Thirst and headaches gave way to two long comas; the second time, he woke up in the war-scarred city of Tsaritsyn, far away from where he’d passed out, and was soon loaded on a train bound for Novorossiysk. There he slowly recovered in an infirmary near the Black Sea port city, and as his faculties returned, he got active in underground work.

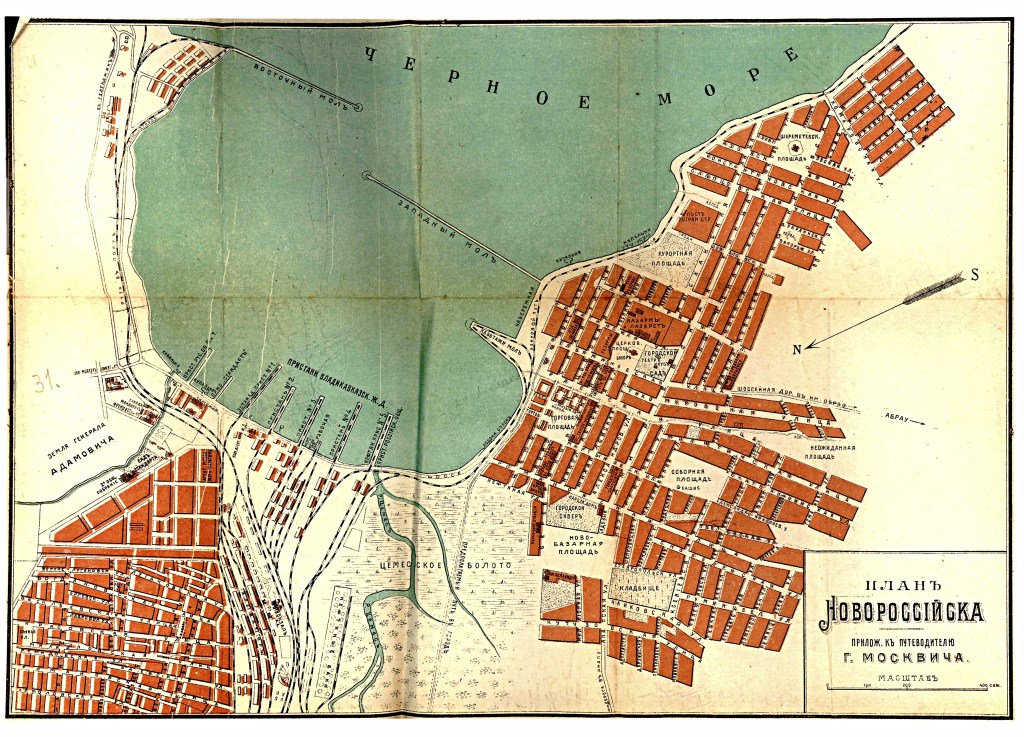

There were partisans in the hills near town, and he stole medical supplies from the infirmary and passed them to these ‘Green’ guerrillas. This close to the port of Novorossiysk, the supplies sent by the British government were piled up.

There was so much in storage that food supplies were lying under the open sky, and still the English continued to send more in ship after ship. Now that the White Army had their backs to the sea, the English had begun to supply all that had been promised when the army had stood near Moscow. The prisoners’ infirmary now enjoyed bed linens and other English hospital linen. In our storeroom lay trunks packed with English food products, including cocoa and dried vegetables. There was more than our cook could cope with.

There was a sand spit within sight of the infirmary where the Whites regularly took people for executions. The patients kept watch on this spot, collected intel and helped escapees. Dune and his fellow captive invalids stole papers from comatose typhus-inflicted Whites and supplied them to Red and Green agents in the city. They had a workshop on hospital grounds where they turned out false documents.

Novorossisyk had already been the site of things so strange and terrible they are difficult to visualise; way back in the fourth episode of this series, we followed the Bolshevik sailor Raskolnikov on his mission to scuttle the Black Sea Fleet. Very soon after that, the port fell to the Whites. Now, less than two years later, it was to witness one of the most surreal and pitiful scenes of the war.

Rostov

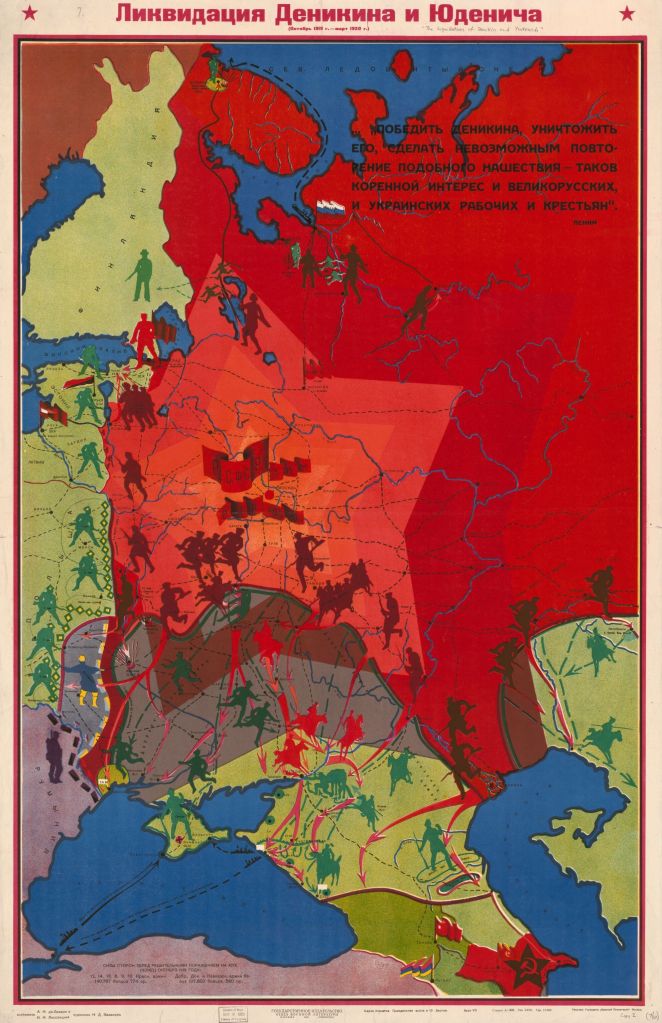

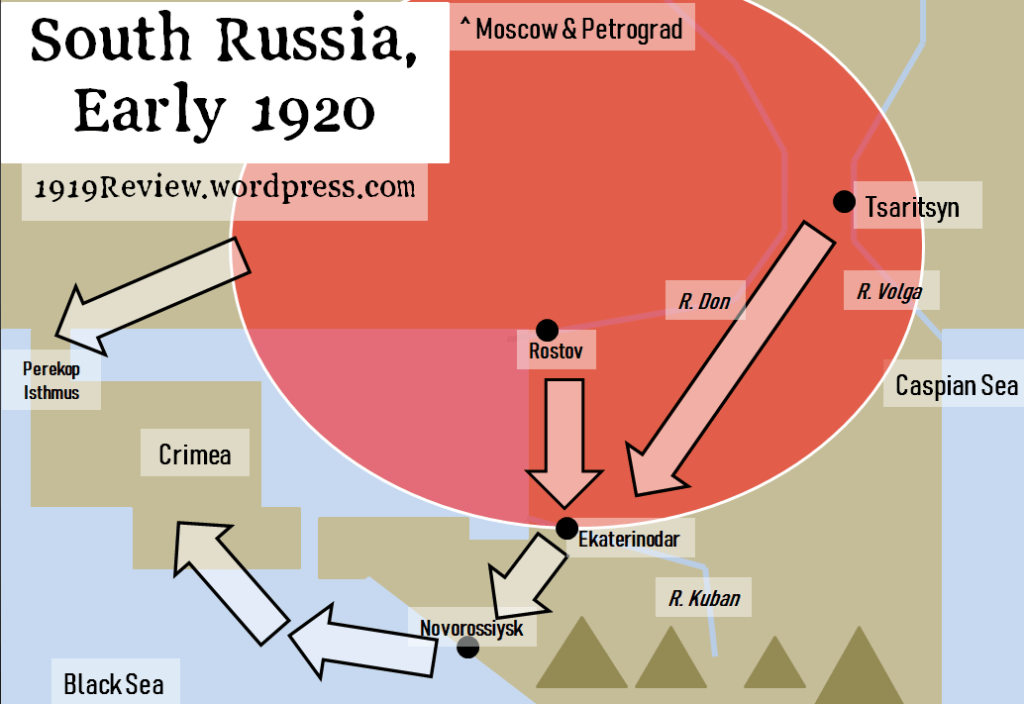

Meanwhile the war was raging on, the Whites falling back, the Reds surging southward: in January Tsaritsyn (later Stalingrad, now Volgograd) saw its last battle of the Civil War when it fell to the Reds. But when the Whites reached their old base area of the Don and Kuban Countries, they rallied. The river Don, as if it was in sympathy, froze to let the Whites retreat across it, then thawed before the Reds could. Alongside this military recovery, the White civilian government, such as it was, promised reforms and tried to juice up some popular support. The Red Army hit the moat of the Don in disarray from its long advance, overstretched and agitated with internal disputes.

The Whites recaptured Rostov-on-Don on February 20th. But the Reds were by this time over the worst of their confusion, and it was the Whites’ turn to have some internal disputes. Denikin had made concessions to the Kuban Cossacks – not enough to stop them deserting, but enough to enrage the White officers. ‘What are we?’ they demanded. ‘Cannon fodder for the defence of the hated separatists?’

The First Red Cavalry Army (which by this time boasted 16,000 riders, 238 machine-guns, nineteen artillery pieces and eight armoured trains) crossed the Don and threatened the rear of Rostov; there was nothing for it but to abandon the town and fall back to Ekaterinodar (the city outside which a shell had killed the Whites’ chief inspirer Kornilov two years earlier) and then, after a short hopeless struggle, on to Novorossiysk.[1]

One of many grim chapters in Beevor’s recent book deals with the entry of the Reds into Ekaterinodar. He describes the summary murder of men falsely identified as officers, Kalmyks being massacred for no apparent reason, and dead White Guards being mounted on a locomotive as trophies. Beevor appears to be repeating contemporary rumours which his source’s author heard second-hand, which is consistent with some of my criticisms of the book. [2] But even allowing for exaggeration and rumour-mongering, such excesses probably did form a part of the picture of the Red Army’s advance in some areas.

Novorossisk

The resumption of Red advance translated into rumours heard by Dune in the Novorossiysk infirmary: ‘The Whites had won victories with the aid of their cavalry, but ever since Trotsky had said, “Proletarians, to horse!” we too fielded a cavalry, and ours beat the Cossacks all hollow. The Red cavalry had captured all the English tanks.’

This was confirmed by what Dune could see with his own eyes; White Guard Russia was visibly shrinking and contracting around him. First, discipline grew lax, and he could get out into the city on errands. Once there he saw the streets fill up with a strange juxtaposition of affluence and squalor: cartloads of expensive household goods, and huge numbers of typhus-stricken refugees. White officers began taking entire battalions to join the Greens. Back at the infirmary, White Army supplies were stolen wholesale now instead of retail.

Moving away and up the chain of command from the humble soldier Dune, the British General Bridges was disgusted: ‘the whole affair was a degrading spectacle of unnecessary panic and disorder, and I urged the government by cable to dissociate themselves from the White Russians who had no prospects and little fight left in them.’ But Winston Churchill, Secretary of State for War and Air, overruled him. So the British remained and took responsibility for the evacuation of White officers and their wives and children. [3]

Suddenly the British project of pumping in great quantities of supplies and war materiel had to go into reverse: now the British were evacuating White officers and their families, and anyone else who could be crammed on board. At the quays, crowds pressed against the British Army cordon and the ships heaved with people. A tank drove slowly over a row of thirteen British aeroplanes, turning them to matchwood so that the Reds couldn’t use them. Then, of course, the tank itself was abandoned. Other engines of war littered the sea floor where they had been dumped. Tearful Cossacks shot their horses.

The other White naval evacuations were disasters, but Novorossiysk was the worst. [4] It was so bad, Denikin resolved to resign as soon as it was all over. The misery, destruction and desperation were extraordinary:

…the waterfront was black with people, begging to be allowed on board the ships… Conditions were appalling. The refugees were still starving and the sick and the dead lay where they had collapsed. Masses of them even tried to rush the evacuation office and British troops had to disperse them at bayonet point. Women were offering jewels, everything they possessed – even themselves – for the chance of a passage. But they hadn’t the ghost of a chance. The rule was only the White troops, their dependants and the families of men who had worked with the British were allowed on board. [5]

Above: the chaos at Novorossiysk.

The 2nd Royal Scots Fusiliers acted as a rear guard, supported by a naval bombardment (one of the ships firing was the Waldeck-Rousseau, which had mutinied the year before). On March 27th the Red Army arrived, lobbing shells after the fleeing ships. By then, 34,000 had been evacuated (A disproportionate number were Volunteers, which suggests the Don Cossacks got shafted).

The Reds found on the quays an indescribable landscape of dead horses and destroyed equipment – but also heaps of intact supplies, such as one million pairs of socks. General Bridges had not been permitted to abandon the Whites, but he had left food and clothing to try to alleviate the suffering of ordinary people in war-torn South Russia. The Reds captured 22,000 White Guards in the town, and 60,000 later surrendered further down the coast at Sochi.

Other Whites fled into the Kuban steppe, where they waged a guerrilla war. As for the Green armies, at the moment of victory they suffered a split between the pro-Communist elements and the various other forces who were in the mix, and soon dissolved. [6]

London

Meanwhile in London, time of death was called on the White cause. Field Marshal Henry Wilson wrote in his diary: ‘so ends in practical disaster another of Winston’s attempts. Antwerp, Dardannelles, Denikin. His judgement is always at fault.’

Several days later he wrote: ‘cabinet at 6pm. We decided, Curzon leading, finally to tell Denikin to wind up affairs and come to terms with the Soviet government. Great joy. Winston fortunately absent.’ [7]

It was neither the first nor the last time the British had decided to withdraw from the Russian Civil War. They were sick of being on the sidelines of the bloody mess, acting as referee and sponsor, and occasionally stepping onto the pitch to play midfield, only to be frustrated again and again by the unexpected strength of the opposition and the shocking failures of their own side. In spite of all this, British intervention continued while the Whites made another throw of the dice. The fact that some tens of thousands of White Guards had escaped in one piece, plus an accident of geography and miitary fortune, gave the Whites an opportunity.

During the chaotic White retreat across Ukraine, one White officer had fought his way through Makhno’s anarchists to reach Crimea. There he held the Perekop Isthmus, the narrow strip of land connecting Crimea to the mainland. This officer, who had entered Ukraine as one of Shkuro’s notorious ‘White Wolves,’ bore the evocative name Slashchev.

Because of Slashchev’s feat the Whites held onto Crimea, an area 27,000 square kilometres in size, or one-third the size of Ireland. The Reds had no fleet on the Black Sea and the Allies had, so Crimea was a natural fortress as well as a base area of manageable size and with a population of over a million. That’s where the British fleet obligingly left those 35,000 evacuated White Guards. We have the strange picture of masses of hardened veterans disembarking at seaside resort towns.

Crimea

The first item on the agenda was leadership. At a Council of War in April, power passed from Denikin to his rival and critic, the ‘Black Baron’ Wrangel. The military chieftains objected on principle to electing Wrangel. To be clear, they did not object to Wrangel himself, only to the idea of electing a leader. So they insisted Denikin appoint him. After the galling experience of handing power to his rival, Denikin had nothing left to do but depart for Constantinople on a British destroyer, never to return. [8]

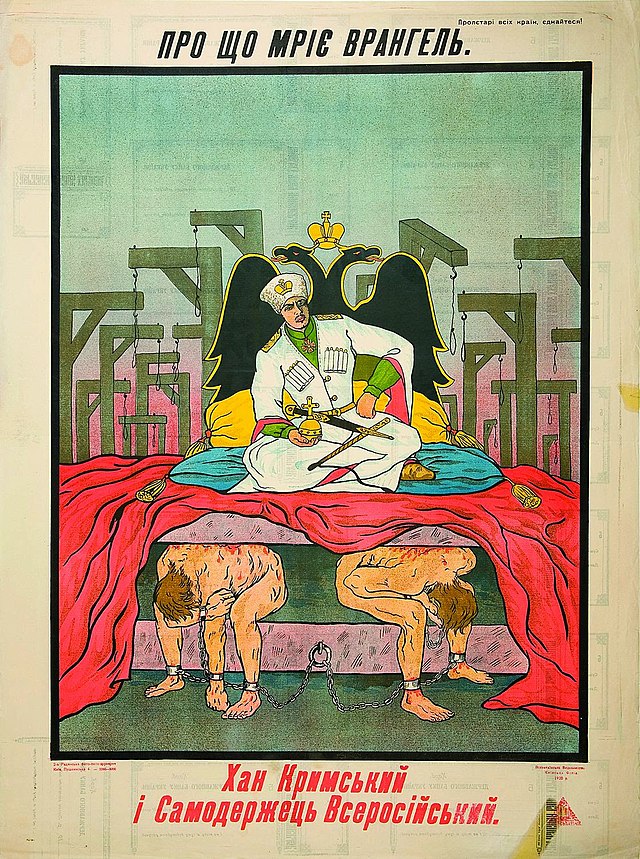

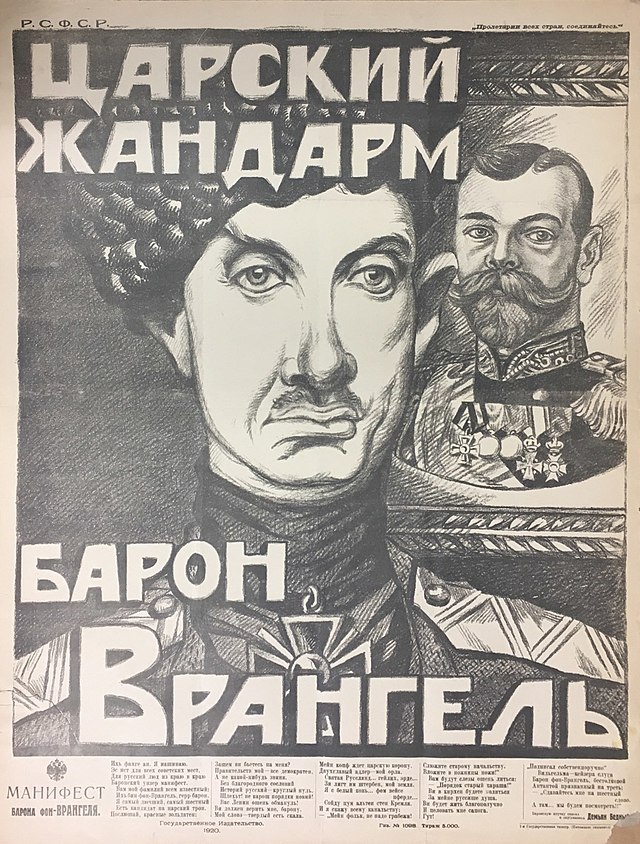

Above: photographs and a poster depicting Wrangel

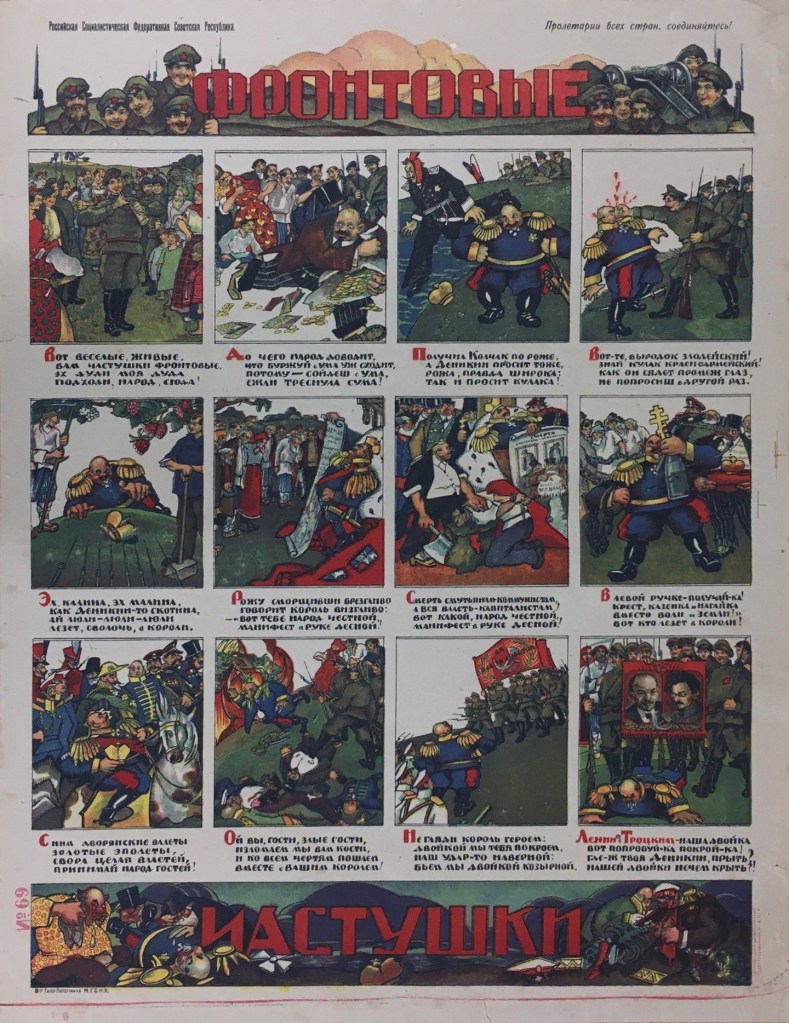

Wrangel was not a graduate of Bykhov prison-monastery or a survivor of the Kuban Ice March, not at all one of the original Kornilov club. But with his height and striking features, he looked the part more than any other major White leader; Soviet cartoons and posters got great mileage out of him.

But there was still a line of continuity going all the way back to those origins as ‘the saga of the Volunteer Army continued in the Crimea.’ The elite ‘colourful units’ that were named after Markov, Alexeev, Kornilov and the others still existed as I Corps. [9] Like his predecessors, Wrangel called himself ‘Ruler’ and his army the ‘Russian Army.’

One of the themes that keeps popping up in this series is the role of the individual in history. Wrangel is a striking case study, because under him a new and distinct White Guard regime emerged in Crimea. Whereas Denikin’s regime was overstretched, ragged and undisciplined, Wrangel’s was every bit as lean and severe as he was.

In contrast to the previous White regimes, there was a functioning government and strict discipline. Reds who deserted were given a fair hearing. Looters were shot. Wrangel’s government would even pass a law redistributing landlords’ holdings to peasants – yes, the Whites were finally ready to cut their losses on that one, and the irony is that Wrangel, unlike Denikin, was actually of the land-owning nobility. His regime also made overtures to Tatars and Ukrainians, and cooperated with the Poles.

(L) Wrangel inspecting White pilots, and (R) his functioning government

Was this all down to Wrangel’s personality?

Perhaps not so much. Actually, the Baron had been a champion of the conservatives within the White movement against the more ‘liberal’ Denikin. Wrangel spoke of the need ‘to make leftist policies with rightist hands’ and pronounced a policy of ‘With the Devil, but for Russia and against the Bolsheviks.’ [10] Every living White Guard, one assumes, had learned extremely harsh lessons in 1919. Popular opinion and practical common sense would have favoured this new approach.

Above, images of Wrangel from the Soviet point of view. ‘Three grenadiers’ labelled Iudenich, Denikin and Wrangel; Wrangel as Khan of the Crimea; and ‘The Tsarist gendarme, Baron Wrangel’

What made this approach possible was the fact that an overwhelming mass of White Guards were now concentrated in a stable, small, self-contained base area. Just as one example of how Crimea insulated the Whites from the chaos that had messed things up before, the Cossacks could no longer do the old loot-and-desert routine. They didn’t have horses anymore, let alone horses that could swim across the Black Sea. The character of the new regime had more to do with the new base than with any other factor. But it is one of those interesting moments when so many things, right down to the physical appearance of the leader, produce the same impression: this was a White army, but leaner and smarter, confronting Moscow with a new type of challenge.

Revolution Under Siege Archive

References

[1] Mawdsley, pp 302-309. Special thanks are due to Mawdsley, on whose book I relied heavily for this post. Dune, 180-198

[2] Beevor, pp 431-2

[3] Kinvig, p 311

[4] Smele,p 140

[5] Kinvig, p 309

[6] Smele, p 140. Dune, p 211. On the Greens, see the notes from Diane Koenker and SE Smith in Dune’s memoirs, p 187

[7] Kinvig, p 312

[8] Mawdsley, p 309

[9] Mawdsley, p 364

[10] Ibid, p 363

The new texture behind the ‘Revolution Under Siege’ text is from the Wikimedia Commons image ‘Rust and dirt’ by Roger McLassus. Not that anyone is eagle-eyed enough to notice, but it is important to credit people