Based on Macbeth: High King of Scotland 1040-57 AD by Peter Berresford Ellis, Frederick Muller Limited, 1980

Peter Berresford Ellis’ Macbeth is a short biography that debunks the version of the medieval Scottish king that we see in the famous Shakespeare play.

But Ellis defends Shakespeare himself, making it clear that the great playwright based his work on the only sources which were available to him in 17th-century London. It is mainly these sources which are to blame, not Shakespeare himself.

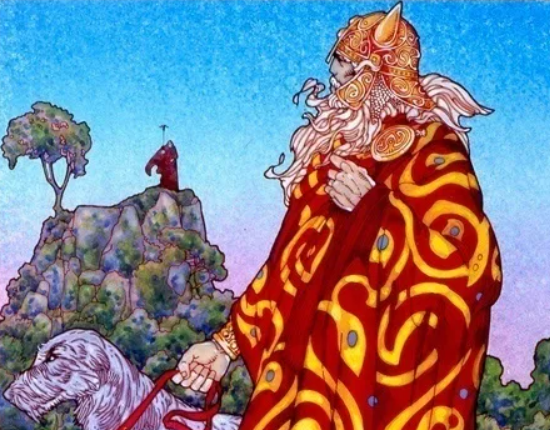

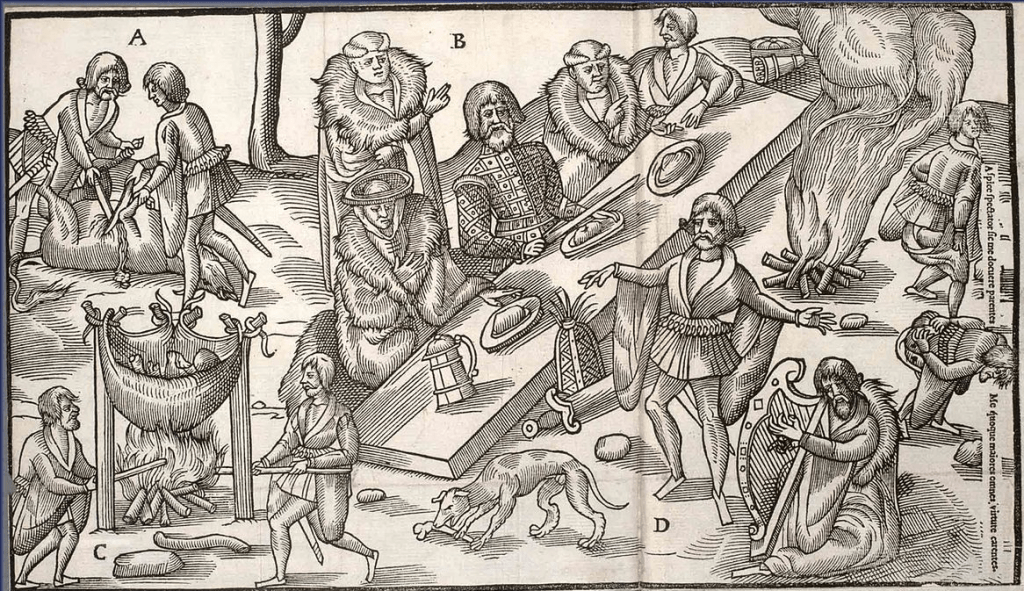

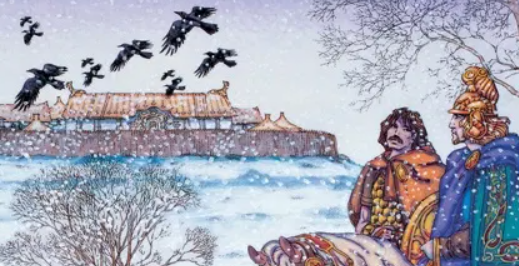

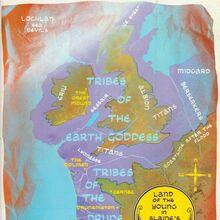

Ellis’ book goes right back to the earliest primary sources, the sagas and chronicles of the Gaels of Ireland and Scotland, of the Anglo-Saxons and Vikings. Macbeth’s age, the mid-11th Century, was a fascinating time, obscured by a scarcity of sources, and it’s worth reading this book just to get a sense of the period.

Shakespeare does make an effort to populate his play with kerns and gallowglasses and other medieval Celtic trappings. But ‘cannons overcharged with double cracks’ intrude into an otherwise brilliant depiction of an early medieval battle (Act 1, Scene 2). Again and again (as we will see below) 17th-Century pathologies rear their heads.

This is one of the great things about Shakespeare. His flagrant anachronisms place his stories in, as Ellis says, a ‘never-never-world’ which makes it easy to apply them, to adapt them, to reset them in new contexts.

School textbooks today will all point out that the play is historically inaccurate. But they don’t go into much detail. Let’s go through it, act by act. By the way, this book was written over 40 years ago and I haven’t read much on Scottish history aside from this. This is all based on what I’ve read in this book and my previous readings on Celtic society. Many of the points below will tie in with Celtic Communism? a series I wrote last year.

Act 1

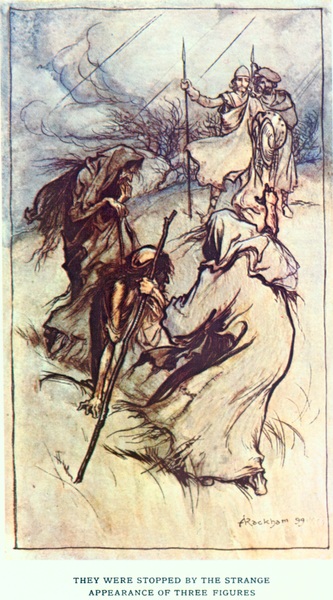

Scene 1: The play opens with three witches. They are not in the contemporary and near-contemporary sources at all. The witch-burning craze was a 16th and 17th century phenomenon. These three characters appear as nymphs or goddesses in Shakespeare’s immediate sources. But Shakespeare knew his audience (his company’s patron King James, author of a book on witches titled Demonology).

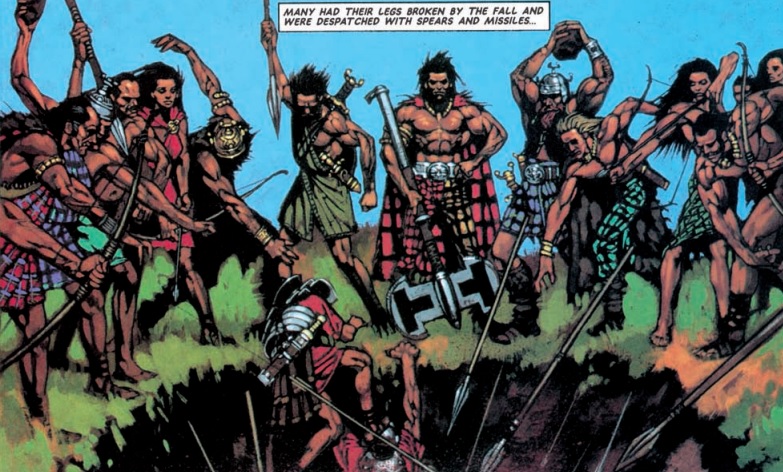

Scene 2: We get a vivid description of bloody battles. Two rebel Scots, Macdonwald of the Western Isles and the Thane of Cawdor, assisted by the Norwegians, are making war on the good king Duncan. Duncan prevails thanks to the assistance of Macbeth.

In reality, this was a war between Duncan and his cousin Thorfinn, jarl of Orkney. Duncan was defeated, and Ellis believes that Macbeth probably fought against him, and caught him and killed him in the aftermath of the battle.

Scene 3: These titles – thane of Glamis, thane of Cawdor, etc – are all wrong. Macbeth was Mormaer of Moray – which was one of the highest positions in Scotland. Banquo, meanwhile, was invented later as a mythical ancestor for the family of King James. He’s another figure who does not appear in the early sources.

The king throws around titles as rewards: Thane of Cawdor, Prince of Cumberland. In the Gaelic political system, these positions were elective. Duncan, by the way, was High King and not King.

Lady Macbeth had a name – Gruoch – and a son by her previous marriage, Lulach, whom Macbeth treated as his own heir. The evil Lady Macbeth is really Shakespeare’s own invention. So none of the evil female characters were in the original sources.

In all of Duncan’s scenes, we see him using the royal ‘we’ and being showered with all kinds of toadying and extravagant flattery. I’m sure this was how kings behaved and were treated in Shakespeare’s day. But I would guess it was not the case in Celtic Scotland.

By the way, although they were cousins, Duncan’s family and Macbeth’s were mortal enemies going back generations. Someone, probably Duncan or his allies, slaughtered Macbeth’s father when Macbeth was a child. This elaborate flattery is therefore doubly inappropriate. The relations between these men should be tense.

Duncan and Macbeth were not just individuals but representatives of rival factions, rival kingdoms even: Moray and Atholl. Or Moireabh and Fótla, Donnchadha and Mac Beathadh– as Ellis reminds us, the people of Scotland spoke Gaelic at this time and for hundreds of years after.

Act 2

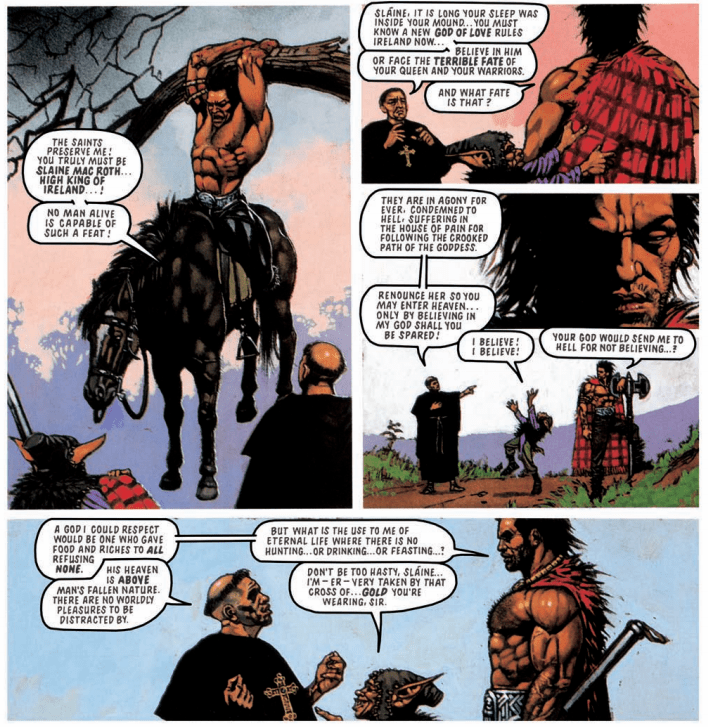

Throughout this Act, killing Duncan is treated as a sacrilege. It is ‘A breach in nature for ruin’s wasteful entrance.’ His blood is golden. His virtues will ‘cry out like angels, trumpet-tongued, against the deep damnation’ that is his murder. He is ‘the lord’s anointed temple.’

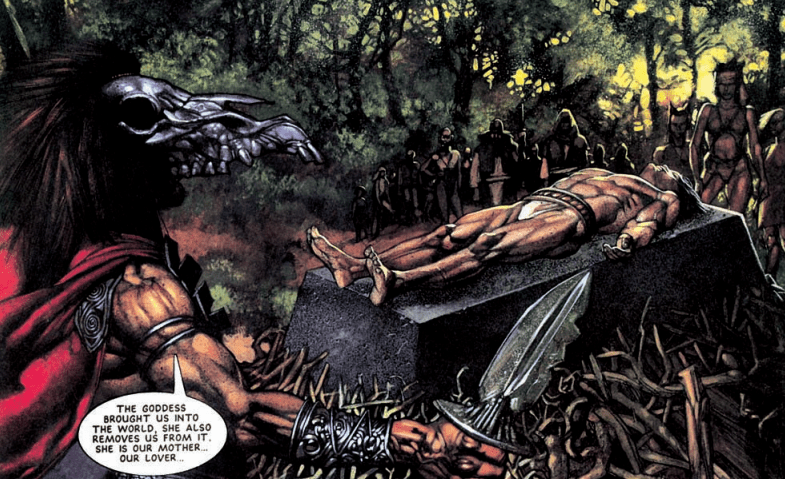

Gaelic Scotland, according to Ellis, would not have seen in that way. They had a duty to depose and kill defective kings. And the historical Duncan was an unsuccessful warmonger.

What would have been seen as sacrilege would be the murder of a guest. Ellis says it would have been impossible. This is because the rules around hospitality were so strong in Gaelic culture.

In Shakespeare’s text, Macbeth’s real crime is not that he killed a nice man – it’s that he killed a king. The Early Modern mind reels at the unthinkable sacrilege. Yet within a few decades of the first performance of this play, the English cut their king’s head off; I think Shakespeare protests too much, and his play manages to channel some of that cultural substance which would go on to flow powerfully into the English Revolution.

At the end, there is a little hint of elective kingship. The characters remark that ‘’tis most like the Sovereignty will fall upon Macbeth.’ But this is only the tiniest hint.

Act 3

Feudal imagery continues – barren crowns, fruitless sceptres. This imagery also suggests primogeniture, which was alien to Scotland at the time.

The play implies that a short time has passed since Macbeth was crowned. The significance of the banquet scene is that Macbeth’s authority and sanity are already starting to unravel. He has had no chance to enjoy being king.

But the historical Macbeth ruled in relative peace and stability for seventeen years. His reign was far longer than those of his immediate successor and predecessor.

The banquet scene is an absolutely brilliant moment in the play. But as we have noted, Banquo was not real.

Act 4

Macduff is another character who was probably invented hundreds of years later. As for the slaughter of his family, another invention.

Act 4 Scene 3 shows England as a wonderful utopia ruled by a saintly king, in contrast to Scotland where ‘new widows howl’ every morning.

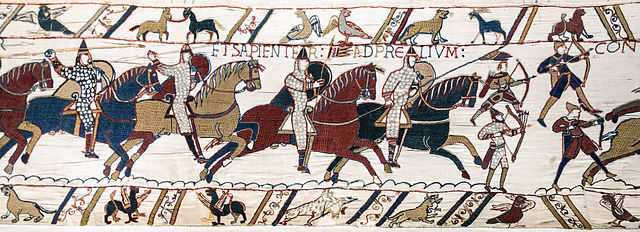

In reality England at this time was torn by upheaval and conflict between Norman, Danish and Anglo-Saxon lords. Scotland only saw one internal revolt during the long years of Macbeth’s reign, and that was isolated and put down quickly. Funny, that! I thought primogeniture was supposed to bring stability.

There is a long conversation between Malcolm and Macduff, a tedious part in what is otherwise such a well-written play, where they catalogue exhaustively all the characteristics of a good monarch. As well as being slow, this is in fact a catalogue of anachronisms.

Act 5

In the final act an English army invades Scotland, supported by a universal revolt of the Scottish people ‘both high and low.’ The people have risen against Macbeth: ‘minutely revolts upbraid his faith-breach.’ Macbeth is holed up in a fort, losing his mind, lashing out in madness or in ‘valiant fury.’ The enemy army marches on his fort disguised behind the boughs of trees. He fights to the last almost alone, his own side deserting him and refusing to strike the enemy. Then he is killed and his severed head is displayed.

How accurate is all this? Let’s start with the good (I’ll have to reach a little).

The depiction of the English-Danish Earl Siward is accurate, including the detail of him losing his son in the battle and his stoic reaction. Ellis goes further into this.

It’s also interesting that Malcolm makes his thanes into ‘earls, the first that ever Scotland in such an honour named’ and also promises to ‘reckon with your several loves and make us even with you.’ The first quote reflects how Malcolm, and more so his descendants, brought many English feudal customs to Scotland. The second quote is true in that he rewarded those who had helped him, including by giving large estates in Scotland to English invaders.

But the rest is fiction. Macbeth met Malcolm and Siward in the field (yes, probably near Birnam), and while he lost he survived, and inflicted heavy casualties. His enemies were so battered they could not follow up on their victory; Macbeth ruled for another three years! That deflates the ‘Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow’ speech, doesn’t it? Ellis reckons Malcolm annexed Cumberland and Macbeth remained High King of Scotland. Three years later, Malcolm resumed the struggle and this time killed Macbeth and took the title of High King. Macbeth was buried with the full honours due to a High King on the holy island of Iona. This distinction was denied to Malcolm when he died.

But Malcolm’s descendants went on to rule Scotland for centuries. The myth of the evil Macbeth had to be invented in order to improve the image of Malcolm, a beggar prince and a foreign-backed usurper.