Emma Donoghue’s The Pull of the Stars begins like a movie sequence full of long tracking shots, following a nurse on her commute through the dark of early-morning Dublin streets in the autumn of 1918.

There are masked men spraying the gutters with disinfectant, children assembling at the train station for evacuation to the country, fear on the tram at every cough and spit: this is the height of the ‘Spanish Influenza’ pandemic.

After what she calls ‘the grippe,’ the next item in order of relevance to our narrator, Nurse Julia, is the ongoing First World War. It’s in its last few weeks, but she does not dare to hope that rumours of mutinies and moves toward peace are true. The war is as inescapable as the pandemic in the way it shows up in a wealth of details in this everyday experience.

The struggle for independence is a distant third, or perhaps it’s even further down the list of priorities for Julia. She passes the burnt-out ruins of O’Connell Street which still haven’t been rebuilt after the 1916 Easter Rising, which she dismisses in her mind as an act of crazy violence by a handful of extremists (Later she says to a rebel supporter, with icy understatement, ‘I got some experience with gunshot wounds during that week.’)

More relevant than the national question is the patriarchal influence of the Catholic Church: it is considered unseemly for Julia to cycle to the church-run hospital where she works.

It could be argued that the author is laying it on thick with the sheer amount of historically relevant things jostling for attention in every paragraph of Julia’s commute. But it’s authentic: these were extraordinary times and history was not something you could escape, least of all in the routine of everyday life. Reconstructing this extraordinary and forgotten moment is an important feat.

Later we will learn that Julia has never heard of Thomas Ashe, the Irish Republican who died on hunger strike in 1917. We never see her reading a newspaper, so it’s believable that the whole thing would have escaped her attention. And it’s not just plausible, it’s kind of refreshing. There was other stuff going on.

Getting caught up in the work

When Julia arrives at her hospital she and the reader get caught up in her work. Before you know it, you’re a third of the way through the book and you care deeply about the current condition of each of her patients. She’s looking after maternity patients who also have the virus; she has to keep these women and their babies alive. It’s one thing after another. We are swept up in the technical (and gruesome) details of the craft and the personalities which populate the cramped room.

When a volunteer arrived to help Julia, I was so invested in the work that I felt a rush of crazy gratitude toward this fictional character.

This character is Bridie Sweeney, and we will learn a lot about her over the next three days. And when we know Bridie’s story, we will question whether it’s enough for Julia simply to save the lives of these women and their infants. Many of them are destined for the orphanages, laundries, mother and baby homes andindustrial schools, a vast half-hidden Gulag which Bridie refers to as ‘The Pipe.’ Meanwhile infants in Dublin have a worse chance of surviving than soldiers in the battles of the ongoing war.

Changing attitude to the rebels

There is the gradual intrusion of Dr Kathleen Lynn, a real-life character. She is at first a troubling rumour – the hospital is scraping the bottom of the barrel and hiring a terrorist! – then a reassuring, compassionate and professional presence in the makeshift maternity/fever ward. We can see Julia, not consciously but no less obviously, changing in her attitude toward Lynn and the other ‘terrorists’ who led the 1916 Rising. People are dying every day anyway, argues Lynn – not from gunshot wounds, but from poverty and squalor caused by capitalism.

Lynn is perhaps a too-perfect character, who always has a clever and compassionate answer to every challenge. But it’s not like she’s Pearse or Connolly; she’s an underrated figure and long overdue a tribute in fiction.

A Covid novel

Like Oisín Fagan’s Nobber, The Pull of the Stars is a book about a past pandemic which was written just before Covid. The writer was not thinking of lockdowns, masks, jabs and Zoom calls. But the mind of the reader is dominated by comparisons.

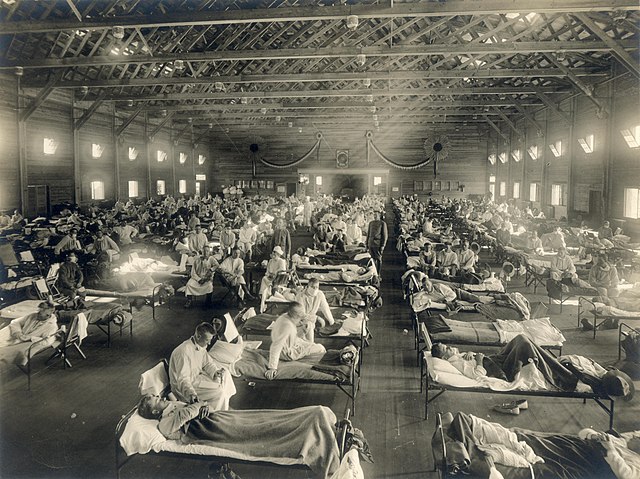

What we see in the book is a lot worse than what Irish people have gone through in recent years, for the simple reason that in 1918-1919 there were apparently no half-way serious public health measures. There was no vaccine. Bad and all as our health service is today, there was no health system worthy of the name in 1918.

The attitude of the state is conveyed in poster slogans. One says: ‘Would they be dead if they’d stayed in bed?’ As Julia notes, it’s much more difficult for working-class people to stay in bed for days. Another says that ‘THE GENERAL WEAKENING OF NERVE-POWER KNOWN AS WAR-WEARINESS HAS OPENED THE DOOR TO CONTAGION. DEFEATISTS ARE THE ALLIES OF DISEASE.’

But there was always a strong element of that in public health messaging during Covid as well – scolding people instead of helping them, demanding sacrifices instead of providing basic supports. The hospital in The Pull of the Stars– overcrowded, understaffed; every nook and cranny turned into a ward, the canteen banished to the basement – will be drearily familiar to many who worked during Covid.

Midwifery

Earlier I said the opening was cinematic, but later on The Pull of the Stars reminds us what movies can’t do but novels can. It is unflinching in its treatment of the details of nursing and midwifery – there is no misguided delicacy, in other words. You won’t see this in Call the Midwife or Emma Willis: Delivering Babies. TV won’t show this stuff, and actually it couldn’t even if it tried.

I don’t know enough about the history of obstetrics to say how accurate it all is, but nothing rang false to me.

Changes

Equally convincing is the way Julia changes. The extreme circumstances, along with a whirlwind experience of love and loss, move her deeply. Lynn’s socialist politics appear to have a catalysing effect. At the end of the novel Julia makes a radical decision which puts her on a collision course with the nuns.

The real reckoning in the novel is not with the pandemic. The ‘Spanish’ Flu merely shines a revealing light on empire, patriarchy, capitalism and the church. Above all else, it’s the horrors of ‘The Pipe’ that bring about change in Julia’s character. I’d bet that the Tuam Babies scandal was closer to the mind of the writer than the Bird Flu or SARS.

There is some implausibility in the ending. But Donoghue has succeeded in convincing us that this was a historical moment rich in implausibility. This is a rich and strange and terrible time when people might do extraordinary things. The choice Julia makes is moreover justified on a thematic and story level – a miracle that is ‘earned’ by tragic losses earlier.

This is a short novel and, I found, a gripping one. I’m interested in this period in history so I drank in all the detail. More importantly, Donoghue’s narrative of a midwife caring for a handful of pregnant invalids is somehow more exciting than any epic action scene I’ve read lately.