Review: Russia: Revolution and Civil War, 1917-1921 by Antony Beevor

I’m writing a series about the Russian Civil War, so I’ve read up on it. I was in a position, so, to notice the blind spots, omissions and distortions in Antony Beevor’s book Russia: Revolution and Civil War which came out last year. Soon after starting the book, I wrote a brief review of just one chapter. I thought I might leave it at that.

That was, until I Googled a few of the mainstream media reviews. Apparently it’s ‘a masterpiece,’ ‘grimly magnificent‘ and ‘a fugue in many tongues.’ Since the moment I was exposed to this gushing, I have felt an urge to point out that the emperor has no clothes. Judged as a work of popular history, Russia is deeply flawed. Judged as a work of anti-communist demonology, it’s spirited but crude. The fact that it demonises the Red side would be a selling point for some, but many have failed to notice what a clumsy demonisation it is.

So I’ll be reviewing the book in a short series of posts. This first post will deal with the things I liked about the book, and then go into some serious criticisms of its one-sidedness, its bias toward the rich, its credulity and its general sloppiness.

Positives

Fortunately, the whole book is not as bad as that one chapter I looked at before. That chapter is merely on the bad side of average. Overall, the book has some strong features which manage to shine through.

- First, it is a detailed narrative history of the Russian Civil War, a rare thing in the English language, which gives the book a certain value in itself.

- Second, Beevor had the help of researchers in Eastern Europe, so there is a wealth of new material here that I haven’t come across elsewhere.

- Third, when it is in narrative mode and not moral judgement mode, the book is well-written. For example, the section on the year 1919 is mostly good, and if I was reviewing only that one-fourth of the book I wouldn’t have much bad to say.

- Fourth: the book deals with White Terror as well as Red. I was honestly surprised because most western accounts pass over anti-communist atrocities in tactful silence. However, even in this treatment of White Terror there are big problems, which I’ll point to below. Another thing to stick a pin in and come back to later: here as elsewhere, Beevor’s own evidence makes a joke of his conclusions.

Not every element of the book is crude. The narrative is strong at times. In short, for its style it is readable, and for its content it is a useful resource. Per-Ake Westerlund has written a useful review in that spirit.

Now, on to the bad points.

What were they fighting about?

In its review the Wall Street Journal asks: ‘If the American Civil War ended slavery, and the English Civil War restrained the monarchy, what did the Russian Civil War achieve?’

If this book was the only thing you ever read about the Russian Revolution, you could be forgiven for asking such a question. The most striking feature of Russia: Revolution and Civil War is its complete inability to see anything positive in the revolution. It’s such a one-sided book, you would probably be appalled to find out there are well-read people (such as me) who regard the Revolution as a great event in world history. If you uncritically accept everything Beevor says, you could only regard me as a dangerous lunatic for holding such a belief.

I suppose it is true that the seizure of the land of the nobility by the peasants was not an enjoyable experience for the nobles. But what about the point of view of the peasants themselves? Weren’t they happy to get more land? And weren’t they a hundred times more numerous than the nobles? Beevor doesn’t even ask the question. But when the peasants began ‘to seize their landlords’ implements, mow their meadows, occupy their uncultivated land, fell their timber and help themselves to the seed-grain,’ he describes it as ‘violence’! (p 50-51)

Was there nothing inspiring in the fact that millions of poor people organized themselves and exercised power through workers’ councils? Apparently not; Beevor dismisses Soviet democracy in a few lines.

The author acknowledges how bad the Great War was, so how can there be nothing positive or even viscerally satisfying for him in the revolt of the soldiers? Was the liberation of women really such a trifling matter that it can pass without any mention at all in 500 pages? How about free healthcare? The world’s first planned economy, which provided healthcare, education and housing to 200 million people and turned a semi-feudal country into the world’s second industrial power?

Isn’t it at least interesting for a military historian that, in the Red Army, formal ranks were abolished and a regime of relative egalitarianism prevailed between commanders and soldiers? That sergeants, ensigns, steelworkers and journalists found themselves commanding divisions and armies, and won? 3/4 of the way through this post I wrote you will find a bullet-point list of similar points.

What, indeed, did the Russian Revolution achieve? Nothing at all – unless we count the achievements.

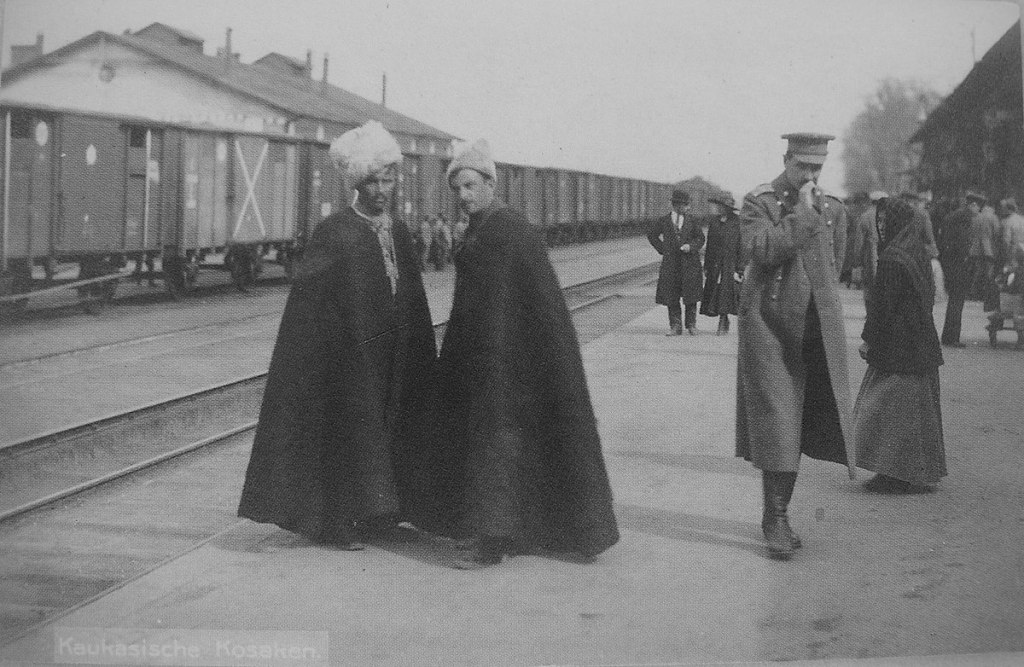

By failing to deal with these points, the book is neglecting to tell us what the Reds were fighting for, or what the Whites were fighting against. The whole thing becomes a leaden nightmare. People in funny hats are dying of typhus and hacking each other to pieces with sabers for no apparent reason.

Every writer on history makes decisions about what to include and what to leave out. Beevor left in all the bits about dismemberment and torture chambers and rats gnawing at the soft parts of people, and left out all of the above. That’s his prerogative. But isn’t it manipulative? Isn’t it morbid? If you are that reader who has never read anything else on the subject, don’t you have a right to feel cheated?

Baking the evidence

The first half of the book, especially, exhibits all the features I outlined in my previous post.

Whenever Beevor comes across a quote from a communist that can be interpreted in a negative way, he proceeds to bake it, to over-interpret it until it is twisted beyond recognition. I imagine him sitting at his keyboard and muttering ‘Gotcha,’ before he ascends to the pulpit with a scowl on his face to deliver a sermon whose theme is the wickedness of the Bolsheviks.

One example: in June 1917 a Menshevik stated that no political party in Russia was prepared to take power by itself. Lenin responded that his party was ‘ready at any moment to take over the government.’ The meaning of this statement is blindingly obvious: they were ready to form a single-party government if necessary, though still open to a coalition government. But Beevor ascends to the pulpit. Apparently it was a ‘startling revelation’ which ‘proved that Lenin cynically despised the slogan “All power to the Soviets”’ and sought ‘absolute control.’ A large part of the texture of the book consists of moments like this.

At other times he caricatures wildly, or presents his own very strange interpretations as if they were factual statements. A street protest in April 1917 is described as a ‘tentative coup’ and a ‘little insurrection’ – ‘tentative’ and ‘little’ are doing a lot of heavy lifting. Any kind of peaceful, democratic Bolshevik political activity – visiting soldiers and talking to them; winning a Soviet election – is invariably described as ‘infiltration.’

Credulity

In addition, Beevor gives credence to dodgy sources. One example: it has been generally accepted for 100 years that the October Revolution in Petrograd was almost bloodless. Or so communist propaganda would have us believe!

Beevor quotes the memoirs of one Boyarchikov, describing a clash at the telephone exchange during the fateful first night of the Revolution. There is a fierce gun battle in which loads of people are killed. After the fight, the pro-Soviet Latvian Riflemen pick up all the dead and the wounded, the enemy’s and their own, and throw them out of an upper-storey window! Next they throw the dead and dying into the river, presumably to hide the evidence (Page 99-100).

This account is obviously absurd. A slaughter such as the one described would have had many, perhaps hundreds, of participants and witnesses, and the press would not have been shy about spreading the news. Why would the Latvians throw their own comrades out of a window and then into a river? For that matter, why would they even do that to the enemy?

You might wonder why someone would make up such a Ralph Wiggum-like story. The answer is that the October events in Saint Petersburg triggered a veritable fever dream of fabricated atrocity stories. The detail about the bodies being dumped in the river was probably invented to explain the lack of corroborating evidence, ie, a massive pile of dead bodies, or a politicised mass funeral.

Beevor repeats some of the discredited rumours from the time: that the Women’s Battalion were ill-treated, and that the Bolshevik Party was funded by ‘German gold.’ In both cases he admits that there’s no evidence, but this doesn’t stop him from bringing it up in the first place, or from writing words to the effect of shrugging his shoulders and saying ‘I guess we’ll never know.’ It’s the old ‘shouted claim, mumbled retraction’ trick.

Only trust the affluent

In addition, he describes too much of the story from the point of view of officials who were trying to suppress the revolution, or members of the intelligentsia and bourgeois who were observing it with detachment at best, or horror at worst. Rarely does he condescend to show what a worker, peasant or rank-and-file soldier experienced or thought. As individuals, working class people enter the narrative only as sadistic persecutors. As a mass, they enter the narrative only as a ‘blindly’ destructive force which ‘the Bolsheviks’ exploit for their own ends.

This is because Beevor only trusts bourgeois and middle-class testimony. Second-hand rumours recorded in officers’ letters or bourgeois diaries are gospel. Later in the book he remarks, surprised, that the Red Army was magnanimous and fair after its conquest of Omsk. He accepts this about Omsk only because he has a first-hand account from a solid bourgeois citizen confirming that it was the case. Instances where the Reds were magnanimous to poor people are not relevant.

When Beevor spent a few pages writing about a failed attempt to get Tsar Nicholas’ brother to assume the throne, I left the following note in my ebook (Here it is with the original typos, because they’re funny):

jesus christ, this is a historian in the 21st century, obsessing about dynastic minutiae while ignlring the sociology and street politics where historyis really beimg decided [sic]

This book must be confusing for the casual reader. How did the Bolsheviks take power? Did they convince everyone to support them with a flashy German-funded ‘press empire’ (Page 76) or was it by prevailing upon a bunch of simpletons to ‘repeat slogans’ until they were blue in the face? (Page 93) In theory both could be true, I suppose, but it doesn’t really explain why a tiny party grew so rapidly to the point where it was able to lead the Soviet in a popular insurrection.

Eyewitness accounts of the February Revolution which described soldiers firing machine-guns at demonstrators were ‘repeated constantly’, he says, but it is ‘impossible to tell’ if these accounts are true, even though he admits that there were machine-guns trained on them and that rifles were fired at them (Page 34). What contempt for the working-class authors of these eyewitness accounts.

His default ‘point of view’ in the narrative is that of the affluent person ruined by the Revolution, or even just inconvenienced. For example he bemoans the lack of ‘privacy’ for wealthy people who had to share their large homes with multiple poor families. Not a word about the lack of privacy suffered for decades by working-class people who lived in slums (often three to a room, often sharing beds) or in company barracks. He laments the fact that formerly wealthy families had to sell their goods in the streets. No hint of sympathy for the vast majority of families, who never got to own such goods at all until after the revolution.

‘Revolution could also reveal that the downtrodden harboured some terrifying prejudices,’ he says, and then tells us an anecdote about a stall holder who made an anti-Semitic comment. Of course, the not-so-downtrodden (Tsar Nicholas, and all those generals and ministers who Beevor loves to quote, and the entire Orthodox Church, and the entire White movement) held the exact same prejudices, but in their case it is apparently not terrifying.

Early on, he briefly acknowledges how squalid and difficult life was for 90% of people under the old regime. But he does so in a way that’s not meant to evoke sympathy or understanding; it’s just more icky details to make the book even more ‘grimly magnificent.’ The effect is to humiliate and dehumanise the poor. And he goes on to humiliate and dehumanise them with a sweeping, derogatory remark here and a prejudiced quote there in every other chapter. Usually through the safe remove of quotation marks, but with insistent repetition, Beevor describes workers, peasants and Russian people generally with phrases like ‘Asiatic savagery,’ ‘children run wild,’ ‘ignorant,’ ‘blind,’ ‘dark mass,’ ‘grey mass,’ ‘anarchic Russia.’

But as we noted, when Lenin calls rich people parasites, Beevor charges him with incitement to genocide!

Stalinism

One reviewer writes that Beevor ‘comments occasionally on the ways events foreshadow (‘give a foretaste,’ he calls it) of horrors to come.’

(As an aside, imagine being so impressed by the phrase ‘Give a foretaste’ that you would note it in your gushing review. Has she never read a book before?)

Russia: Revolution and Civil War actually makes no mention of Stalinism, of the later development of a bureaucratic tyranny that was responsible for such crimes as the Great Terror of 1936-39, the catastrophe of forced collectivisation and the mass deportation of minorities. This is probably because the book is too busy alternating between narrative and moralising to bother with analysis, but it is actually refreshing. Beevor does, however, set things up so that his star-struck reviewers can easily kick the ball into the net: they repeat in chorus, like the sheep from Animal Farm, that this book proves Lenin was just as evil as Stalin.

The reviewers don’t show any understanding that the violence and suffering of the Civil War was completely different in scale, in context and in character from the atrocities of Stalinism. Nor do they appear to suspect that anyone apart from the Bolsheviks might have been responsible for the Civil War and for the violence and suffering that ensued. More on that in future posts.

Sloppiness

Russia: Revolution and Civil War is often sloppy. Beevor repeats several times that Lenin was cowardly, but provides only one example (he went into hiding when the government wanted to arrest him, which seems pretty reasonable). Then he goes on to provide several examples of the Bolshevik leader being personally brave. Each time he remarks on it as a strange exception! Similarly, he says that Lenin is intolerant, but goes on to note one ‘exception’ after another. He doesn’t modify his characterizations, just lets them stand even when they’re full of holes.

Lenin is a key character in the first half of the book, but disappears in the second half – which suggests the heretical idea that maybe he didn’t have complete totalitarian control over events. The atamans of Siberia are introduced – then never followed up on. The narrative ends with Kronstadt, as if the author simply got tired; but at this point the Whites were still in Vladivostok. The introduction and conclusion are insubstantial, especially in comparison to the leaden weight of the book. They are like the wings of a fly growing out of the flanks of an elephant.

Another confusing point: Beevor notes in passing, half-way through the book, that Lenin was good friends with the writer Maxim Gorky. Up to this point Beevor has frequently quoted Gorky, always cherry-picking his most extreme criticisms of the Bolsheviks, never giving a more balanced impression of Gorky’s politics. The reader will wonder how Gorky could possibly stand to be in the same room as Lenin, and how for his part the ‘intolerant’ Lenin could be friends with Gorky. If reality corresponded to Beevor’s unbalanced account of the Revolution, then Gorky would have lasted about six weeks before being shot by the Cheka. As opposed to having a park in Moscow named after him!

As I noted before, much is made of the Cheka in December 1917 – all twenty of them. The development of this institution is not described in the rest of the book either; the Cheka just enters stage left and immediately starts slaughtering people. More on that next week.

In the chapter I reviewed before, Beevor was simply too strident and excitable to give an inch on anything. In the examples above he’s more conscientious, mentioning facts that are inconvenient to the case he’s making. But in failing to reconcile his characterizations with the evidence, he is making a bit of a mess that will leave readers scratching their heads.

And there I will leave you, perhaps scratching your own head; if you read the book and thought Beevor was courageously bearing moral witness to some hitherto-undiscovered chapter of history unsurpassed in horror and squalor, I hope I’ve given you something to think about.

Please subscribe and keep an eye out for Part 2 of this review.