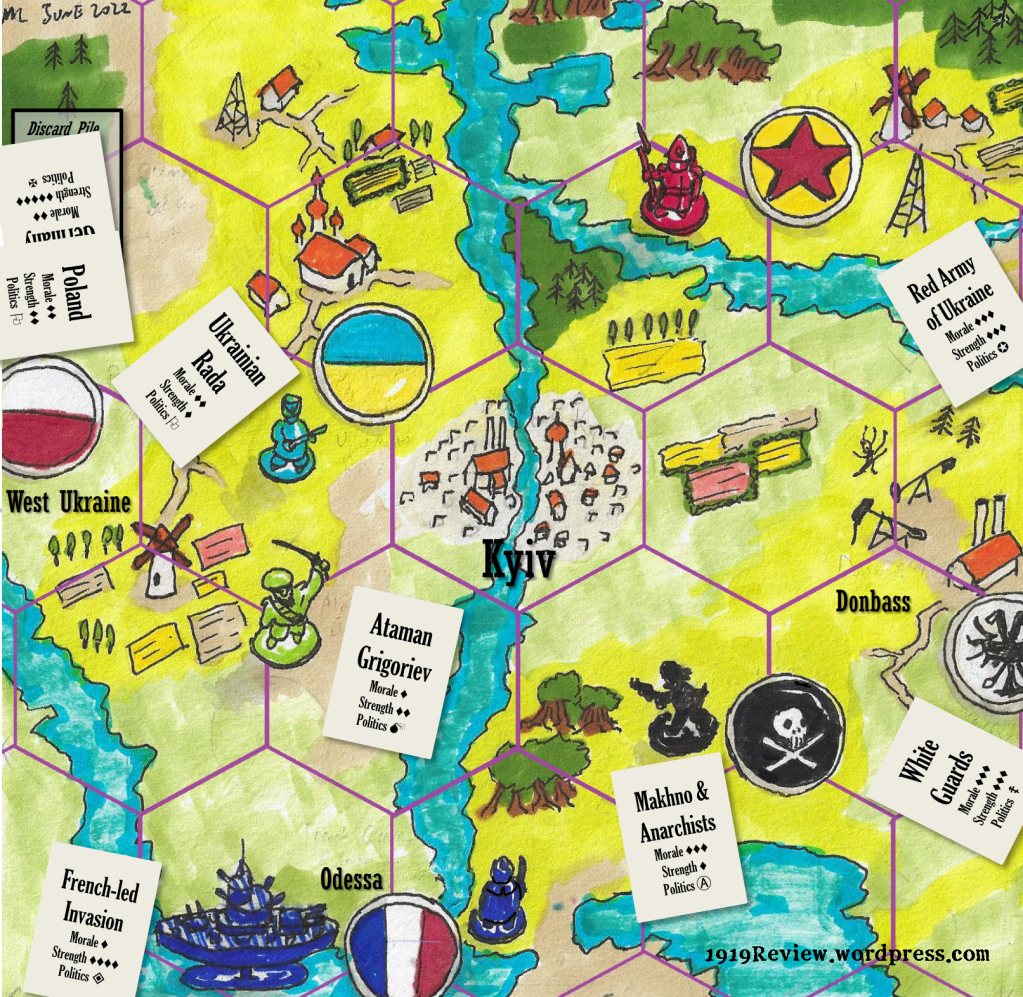

This post continues our explainer on the main factions contending for power in Ukraine in 1919. Note the factions we already looked at last week: the Ukrainian Rada and the White Guards. The German military and their puppet Hetman are already out of the game, and in the east the new Polish state is muscling in.

1. The Reds

The Reds supported self-determination for Ukraine and said so before the world many times. Their preference was for Ukrainian autonomy within a federation, and language and cultural freedoms. This was no less than what the Rada had called for in 1917: ‘Long live autonomous Ukraine in a federated Russia.’[i] The difference between Rada and Soviet was one of class.

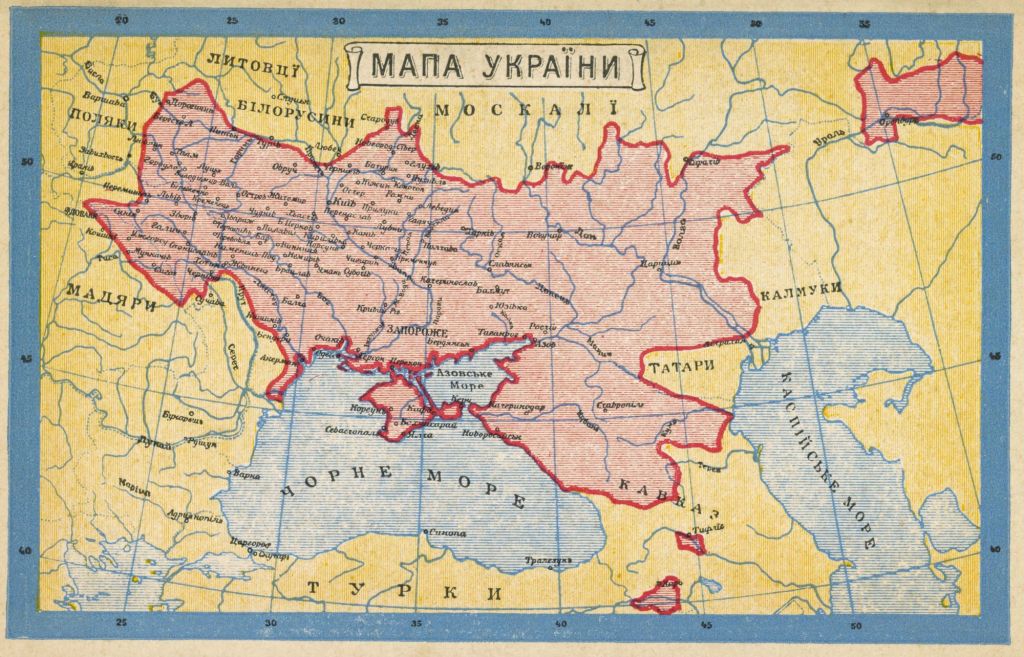

The Red Army entered German-occupied Ukraine in September 1918. After the German Revolution, intervention gathered pace. On 30 November a Ukrainian Red Army was officially founded.

In early December a 3-day general strike broke out in Kharkiv, in Eastern Ukraine, and a revolution from below installed Soviet power in the city. Note the contrast between 1919 and 2022: Kharkiv, which has a large Russian-speaking population, has held out against the Russian invasion up to the time of writing. In 1919 it went Red almost without a fight.

According to EH Carr, the fact that the Communists were unable to organise a revolution directly in Kyiv shows how little active support they had in Ukraine.[ii] But after the events in Kharkiv, the Reds took just two months to cover the distance to Kyiv. In February 5th the Ukrainian Red Army captured Kyiv from the Rada. In contrast to the bloody and destructive five-day struggle between Red Guards and Rada in February 1918, and in stark contrast to the fiasco which Putin presided over in 2022, in 1919 the Reds ‘were greeted by the population with every display of enthusiasm.’[iii]

The Ukrainian Red Army was a horde of Red Guards and partisan units, a throwback to the freewheeling revolutionary days of early 1918. As if to underline this, the Red commander was Antonov-Ovseenko and one of his main officers was Dybenko; these two men had led the October 1917 insurrection in St Petersburg.

The war in Ukraine in 1919 was a war of loose ‘detachments’ and charismatic leaders, sudden spins of the wheel of fortune, and unstable alliances. ‘Being in an early phase of revolutionary ferment,’ according to Deutscher, it was ‘congenial ground’ to the left wing of the Communist Party.[iv]

The Red Ukrainian regime made rapid gains but it was soon overstretched. It was too aggressive on the land question, and dismissive on the national question. Instead of taking the land of the nobility and sharing it out, the Reds decided to turn this land over to state farms. The Ukrainian peasants might have just about tolerated the seizing of food, but this added insult to injury. Huge numbers of peasants rose up in rebellion.

‘In Ukraine today historians argue that Great Russian chauvinism coloured the whole of Bolshevik policy toward Ukraine in this period.’[v] Many Bolsheviks – especially, for some reason, Ukrainian Bolsheviks – were dismissive of the country’s national identity. But the general picture is of a movement with a real social base within Ukraine, in the cities especially but also among many peasants. The idea of the Reds as an imposition from outside is only tenable if we decide arbitrarily that Russian-speakers and Jews cannot be regarded as Ukrainian. The early missteps were later rectified thanks to intervention from Moscow – which goes against the impression that it was Russian imperial chauvinism. If we look back through the prism of later events, especially the famine and terror of the 1930s and the ongoing war, we will lose sight of this. Something very different was going on here.

Later in 1919 and into 1920, as noted above, the Ukrainian Reds, urged thereto by Moscow, adopted more sympathetic policies on land, food and the national question.[vi] But early 1919 was characterised by bold advances, impressive in the short term but storing up huge problems in the longer term.

The civilian administration of Red Ukraine was threadbare. The military presence was more fleshed-out, but not by much. The Dniepr River runs roughly north-south through the middle of Ukraine – from Chernobyl by the Belarus border to Kherson on the Black Sea. The commander-in-chief of the Red forces, Vacietis, wanted this to be the line at which the Red forces stopped short and dug in. But Moscow could not control Antonov-Ovseenko, and in any case Antonov-Ovseenko could not control his Red Guards and partisans. As winter turned to spring they swept on into the western half of Ukraine, carried on their own momentum.

At first the Red advance appeared to be successful. But the overreach had terrible consequences. One was that the Reds ended up dependent on deeply unreliable allies.

2. The Warlord

The civil war in Ukraine, like that in Siberia, was a war of atamans. An ataman was a charismatic warlord who raised and led an army in wild pursuit of some quixotic, obscure or horrifying programme.

How would one go about becoming an ataman? What must you have on your CV? Below is a step-by-step guide for this career path, illustrated with reference to Nikifor Grigoriev, the foremost warlord of Ukraine. Grigoriev was a military officer who, by the hour of his death, had joined or tried to join almost every single one of the contending factions mentioned here.

Step One: Have murky origins

Grigoriev ‘constantly emphasized his Ukrainian origin, called for the destruction of Russians, but at the same time for some reason had a Russian surname’[viii] – the solution to the mystery is that he replaced his real name, Servetnik, with the more Russian-sounding ‘Grigoriev.’

And here we encounter another Lviv or Derry, because it is variously spelled Hryhoriiv and Hryhor’yev.

Step Two: Join the Tsar’s army

Apart from two years of elementary education, Grigoriev’s only school was the Tsarist military. Service as a Cossack cavalryman in the Russo-Japanese war taught him to fight and to lead. After the war followed eight years as either a tax official or a cop. Then in the Great War he returned to the cavalry, and won medals for his courage and skill.

Step Three: Make a lot of friends

He is described by contemporaries as a rude, ugly, heavy-handed man who spoke through his nose. But ‘the soldiers liked him for his recklessness, eternal drunkenness and simplicity in relations with the lower ranks. He was able to convince the rank and file to go into battle, often setting a personal example.’

Step Four: Find a political cause

Grigoriev took part in the soldiers’ committees during 1917. He eventually joined with Semion Petliura and the Rada (Ukrainian Nationalists), and became a Lieutenant-Colonel in its army in 1917-1918.

Step Five: Be fickle

When the Germans booted out the Rada and brought in their puppet Skoropadskii, Grigoriev sided with the Hetman and served in his forces. He may even have participated in the coup. But after a few months he joined the Rada again in their uprising against the Hetmanate.

Step Six: Raise hundreds of fighters, then thousands

He returned to his native Kherson region and convinced 200 middle peasants to fight alongside him. They attacked the Hetman’s police in order to lure out a German punitive detachment, which they defeated. Next they ambushed an Austrian train and made off with enough rifles, machine-guns and grenades to equip a force of 1,500.

This was all in the context of a developing revolution against the Hetman, which culminated in November 1918. In December, Grigoriev led 6,000 rebels into the town of Mikolayiv, seizing it from the Allies, the Germans and the Hetman’s troops.

He threatened the Germans: ‘I’m coming at you […] I will disarm you, and our women will drive you with clubs through the whole of Ukraine to Germany itself.’

Step Seven: Insist on your own independence

Soon, virtual dictator of a large swathe of southern Ukraine, Grigoriev began to turn against Kyiv, insisting on his own independence but also demanding to be made minister for war. He began to flirt with the left even while saying that ‘Communists must be slaughtered’ and threatening to attack striking workers. He joined the Borotbisti, the Left SRs of Ukraine, who were in alliance with the Communists.

Then the French military landed at the Black Sea ports of Ukraine. Petliura was hoping for aid from the French, so he forbade Grigoriev from attacking them. Angered by this, the warlord changed sides once again. He went over to the Reds.

This is not the last we’ll be hearing of ataman Grigoriev.

3. The Black Army

The village of Huliaipole lies in south-east Ukraine, some way inland from Mariupol. There, in 1907, a local school teacher named Nestor Makhno led a peasant protest movement. Makhno was an anarchist-communist. He may have absorbed from his upbringing the Cossack tradition of fierce independence and self-government. The Bolsheviks looked to the working class, but Makhno looked to the peasants.

In 1907 he was arrested and exiled. But in the days of the Revolution he surfaced again. Ten years after his failed rising in Huliaipole, he was elected leader of its soviet.

Summer of 1918 found him in Moscow. He had friendly interviews there with Communist leaders such as Lenin and Sverdlov. But Makhno believed that all state authority was oppressive and counter-revolutionary. He was unimpressed by the anarchist groups which operated freely on Soviet territory.

He returned to Huliaipole in autumn 1918, leaving behind the ‘paper revolution’ of the urban anarchists in favour of rifles and guerrilla attacks. He organised a partisan band, displaying exceptional ability in battles with the forces of the German puppet Skoropadsky.

Then the German empire crumbled and Ukraine became a political vacuum overnight. He organised his partisan band into a stateless peasant commune centred around Huliaipole and defended by a force numbering in the thousands, the Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine.

The Anarchists travelled on horses and carts, loaded down with all kinds of weapons: ‘curved swords, naval cutlasses, silver handled daggers, revolvers, rifles and cartridge pouches made of oilskin. Enormous black and red ribbons flew from every kind of hat and sheepskin cap.’[ix]

The Whites were among the first to confront the Black Army. Mai-Maevsky warned his troops about Makhno: ‘I don’t doubt your ability, but it is not likely that you will manage to catch him. I am following his operations closely and I wouldn’t mind having such an experienced troop leader on my side.’[x] Makhno’s mode of warfare was mobile. For example, as early as November 1918 his troops captured Ekaterinoslav (today Dnipro) simply by boarding a train in disguise, pulling up to the main station, then drawing their weapons and charging out. But they abandoned the town just three days later and returned to guerrilla struggle.

In early 1919 Makhno’s ‘Black Army’ joined the Red voluntarily. One Red Army division was co-led by Dubenko, Grigoriev and Makhno.

Conclusion

We leave it there in early 1919. The Reds are in control of a vast area but stretched thin, and things are about to go sour for them. Soon Ataman Grigoriev will change sides once again. In future posts in this series we will also look more closely at the Anarchists and the Ukrainian nationalists. Future posts will also explore what happened when the French military blundered into this mess with an invasion of Ukraine’s Black Sea coast. And keep an eye on those White Guards in the Donbass.

Go to Revolution Under Siege Archive

[i] Smith, 128

[ii] Carr, 306

[iii] Again, Carr, 306

[iv] Deutscher, The Prophet Armed, 360

[v] Smith, 186

[vi] Smele, 102. Smith, p 186: ‘Thanks to Lenin’s intervention in December 1919, Russian chauvinists had been removed from the leadership of the Ukrainian party, and the absorbtion of the Borot’bisty, a left-wing splinter from the Ukrainian SRs, finally gave the party cadres who could speak Ukrainian and had some understanding of the needs of the peasants.’

[vii] Deutscher, 364

[viii] Most of my information on Grigoriev comes from this very informative essay: http://militera.lib.ru/bio/savchenko/04.html/index.html

[ix] Beevor, 261

[x] Beevor, 260