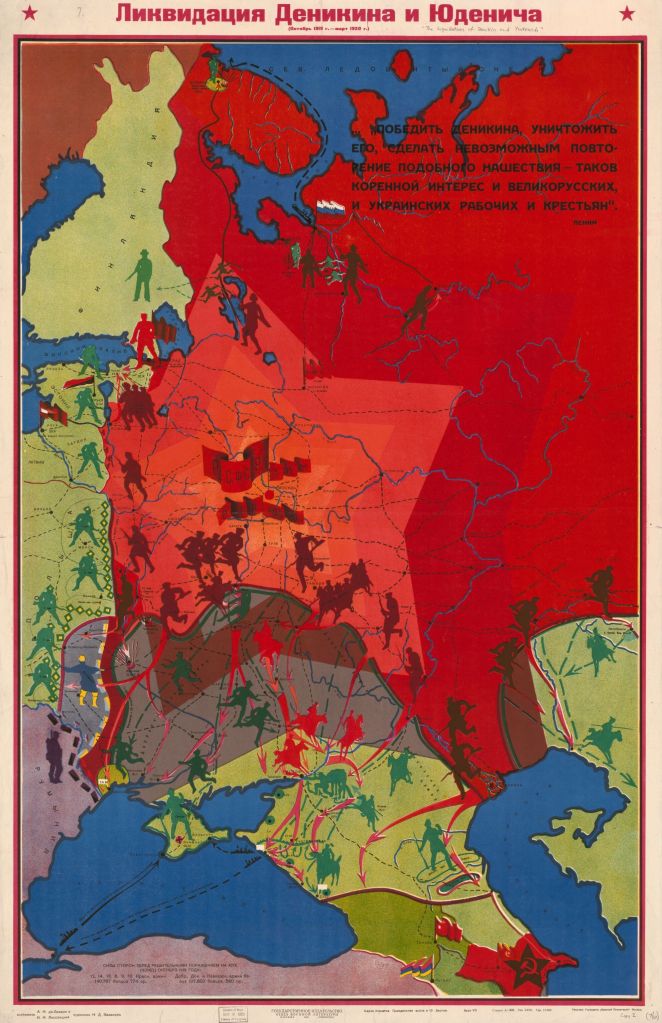

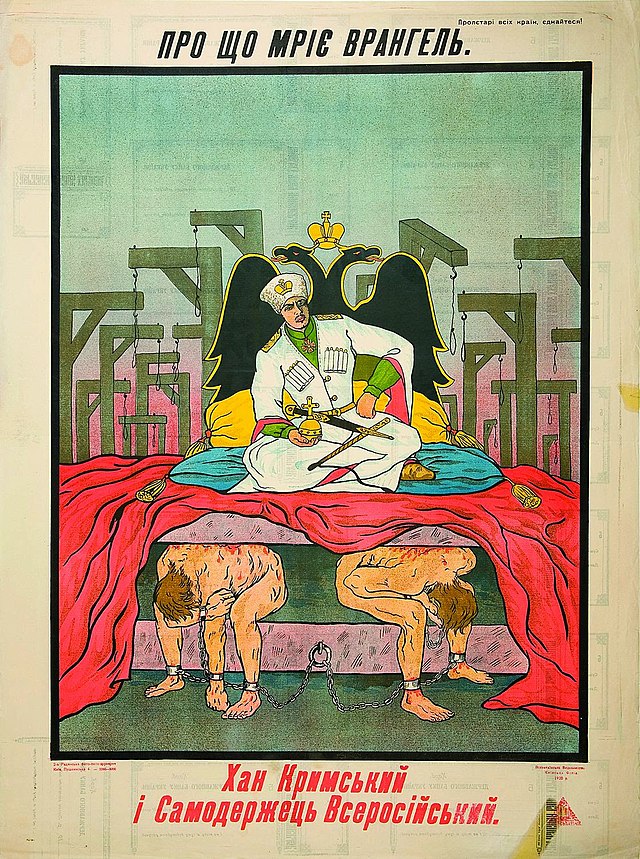

In Part 1 of this conclusion we looked at the popularity of the Reds, the anti-democratic spirit of the Whites and the terrible impact of foreign intervention. The Soviets were popular and progressive. They were attacked in a brutal civil war, and they have been lied about and misunderstood ever since.

But that doesn’t mean they did nothing wrong. For the first half of this post we’re going to look at the question of terror. Finally, we’re going to ask whether the Civil War led to Stalinism.

Terror

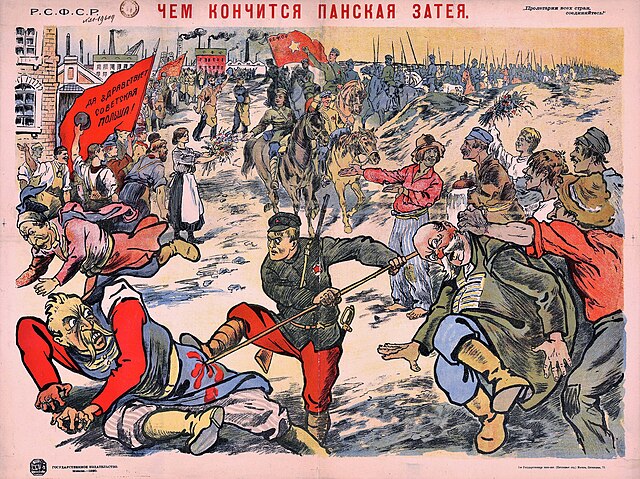

The most disturbing part of the Civil War is the use of terror by the winning side. ‘After the outbreak of Civil War,’ writes Fitzpatrick, ‘the Cheka became an organ of terror, dispensing summary justice including executions, making mass arrests, and taking hostages.’ According to Fitzpatrick, terror encompassed ‘not only summary justice but also random punishment, unrelated to specific guilt […].’ [1]

Deutscher sums up the violence in a vivid phrase: ‘terror and counter-terror inexorably grew in a vicious and ever-widening spiral.’ But he does not elaborate much beyond saying that the Reds ‘did not shrink from the shooting of hostages’. [2]

Smith writes that ‘the extent to which the new [Soviet] regime relied on violence is now much clearer than it once was’ – for example, in Deutscher’s time. But he adds that it is also better understood to what extent all sides relied on violence. [3]

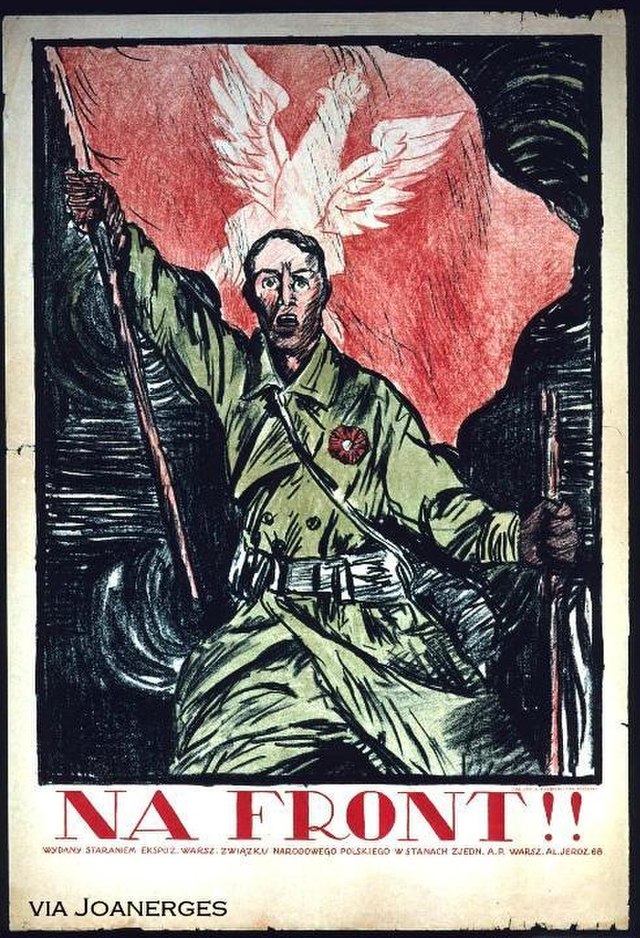

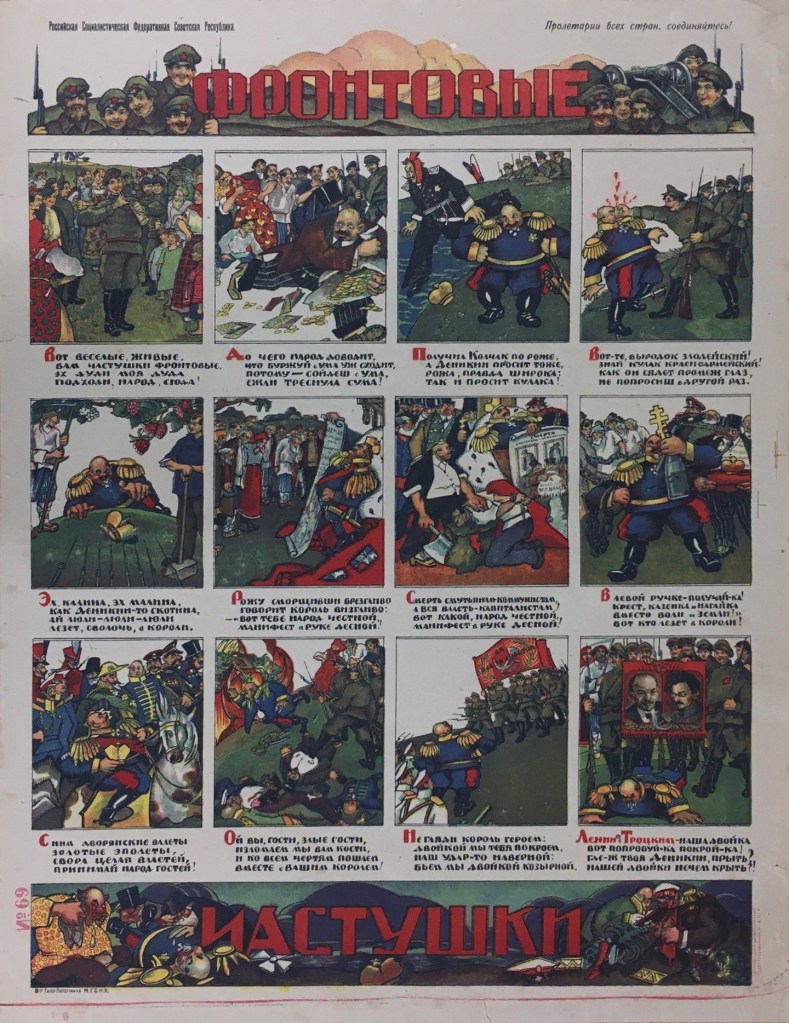

My own reading bears this out. There’s no indication that Red Terror was in any sense worse than White Terror. All sides, from Makhno to Piłsudski and from the Soviet regime to peasant insurgents, used terror as a weapon. These were the grisly rules of this war.

The question is: Who wrote the rulebook? Who were the instigators of the unconstrained use of violence?

Who instigated terror?

In 1917 itself the conduct of the Bolsheviks was markedly restrained and humane; massacres committed by enraged sailors were condemned. The early White Guards were not just spared but paroled.

Late in 1917 White Guards massacred Red Guards within the walls of the Kremlin. Even before the start of Civil War proper the two foremost leaders of the White armies, Alexeev and Kornilov, defended the practise of shooting all Red prisoners. Kornilov was public and outspoken, calling for as much terror as possible and declaring that he was ready to kill most of the population if necessary.

From May, we have the Civil War proper. Unrestrained terror against ‘Bolsheviks’ was the rule during the White risings of Spring-Summer 1918. At Omsk, according to a Right SR witness, 2,500 captive Red soldiers and workers were massacred. At the hands of Ataman Dutov, hundreds were buried alive. These are just a few examples of many to show that the Whites got a big head-start on terror. White terror was decentralized and unsystematic throughout the war, but practically every faction engaged in it.

The White head-start on terror is an obvious and clear fact to me when I look at the timeline. But none of my sources talk about it.

Repression under the Soviets

Red Terror ramped up gradually over the summer and began in earnest with an explosion of violence in September 1918. It kept raging in local peaks and troughs until the end of the war.

The Soviet regime’s violence was not premeditated. It was a response to a crisis not of its making. Most of the country’s territory had been seized – not by a popular revolt against ultra-left excesses, but by a well-armed minority and by foreign armies. The insurgents were killing Soviet-aligned soldiers and civilians by the thousand long before the Soviets responded in kind.

The case for Red Terror was made openly. The Communists justified it by pointing to the crimes of their enemies, and promised it would be set aside as soon as possible:

The proletariat who strive for equality of all human beings, have no longing for dictatorship with terrorism, and do not themselves choose that tactical course. As soon as the situation permits of it they will forego it. In the process of the Socialist revolution they will always seek to discover whether this or that section of the bourgeoisie can be induced to join with them in the exercise of power, whether the circle of those possessing equal rights is not capable of extension, and they will greet the day with ringing of bells and shouts of joy in which all chains will disappear […]

Karl Radek, ‘Dictatorship and Terrorism’ Chapter 6 https://www.marxists.org/archive/radek/1920/dictterr/ch06.htm

Radek also emphasized that the curtailing of soviet democracy and the security measures in his own country were not a model for other countries to follow.

The Soviet Union needed a severe security regime in order to survive this war. The Communists in Baku, Azerbaijan stuck to peaceful methods and ended up being executed. The problem is this: what the Soviets actually did went beyond the kinds of measures covered by Trotsky’s and Radek’s arguments. We have covered some of the gruesome details before in this series.

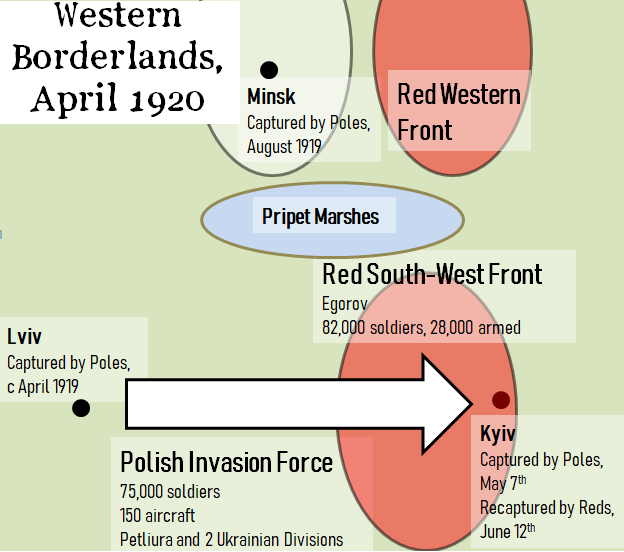

Two dreadful massacres early in 1918, at Kokand and Kyiv, were outliers: carried out by non-Bolsheviks in peripheral places far from central oversight. But it is a problem that they are neglected in any Soviet sources I’ve come across.

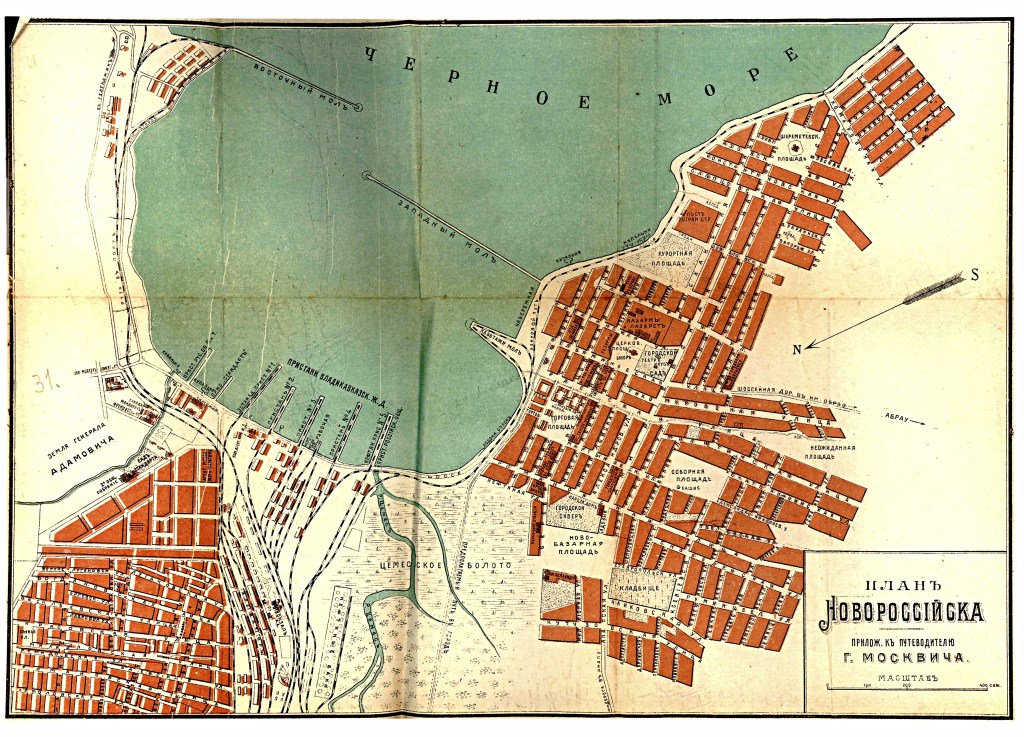

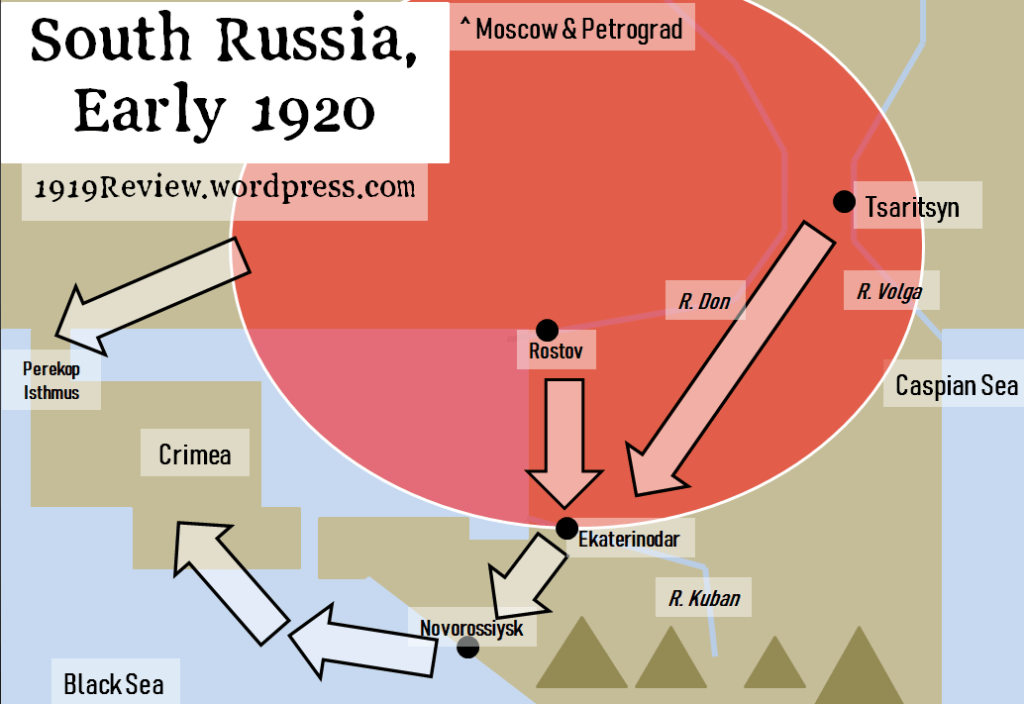

Some of the worst excesses, including the above, occurred in regions that were not predominantly Russian – such as Astrakhan and Crimea. The Bolsheviks took an inspiring stand on the question of national liberation – but the age-old racism and chauvinism of the Russian state found expression in the severity with which some of the agents of the Revolution acted when surrounded by non-Russians.

Revolutionary movements in the future must not take the same road. Terror had a brutalizing effect on the Soviet state and on its supporters. The Red side never endorsed torture – but there is evidence that it happened in some places. Can that be a surprise, when the Communist paper in Petrograd in September 1918 literally called for blood? On the pretext of deterring counter-revolutionaries, violence could be used maliciously. It was often counter-productive, triggering revolt. All this is on top of the cruelty and waste, which go without saying.

‘Ideas learned under fire’ included many negative and paranoid ideas – in other words, trauma. The idea learned from Baku or Omsk in 1918 – that one must take ruthless measures against any stirring of counter-revolution – was a very harmful idea when applied generally.

On the other hand, the English-speaking reader is never challenged, in accounts of the Russian Revolution and Civil War, to imagine how his own government might react if foreign armies and insurgents seized most of its territory. 9/11 was enough to bring out the US political establishment in open defence of torture.

The Soviet regime was under unimaginable threats and pressures. This popular and progressive government had a right to fight for its survival. Ultimately these pressures and threats caused it to stoop to inhumane and counterproductive measures when it should have held firm to a line which might have better balanced security concerns with humanitarian principles.

Did the Civil War lead to Stalinism?

Repression dismantled

Some accounts narrate the executions in Crimea and after Kronstadt in a way that leaves the reader believing that the repressive apparatus built up during the Civil War was kept in place afterwards. In fact, the Cheka was radically cut down, most of its staff let go and its powers curtailed. The use of executions ‘diminished into insignificance.’ The system of prison camps used during the Civil War was shut down; there is no direct continuity between it and the notorious Gulag system. The Cheka, renamed OGPU, was left in charge of only a small number of prisons.

The criminal justice system in the Soviet Union in the 1920s was progressive and lenient. Exile was abolished, prison sentences cut down, crimes caused by poverty judged lightly, non-custodial sentences preferred. Prisoners were paid for work, educated, and often allowed to live outside the prison. The imprisoned population in the whole Soviet Union was under 200,000 in 1927 – likely an overcount as many sentences were shorter than a year.

In other words, repression actually was a Civil War emergency measure.

There were also around 8,500 people in harsher OGPU-run facilities. In 1929, the year Stalin’s regime began its notorious campaign of forced collectivization, 60,000 were transferred from the prisons to new OGPU unpaid labour camps. ‘[T]he network of camps grew to embrace 662,000 by the middle of 1930, and it was to grow within another couple of years to nearly two million.’ [4]

From 8,500 to two million in a few years – that’s a historic rupture.

This leads us on to the second main point of this post. The society which emerged from the war fell a long way short of, say, what Lenin envisaged in The State and Revolution. But it fell even further short of totalitarian Stalinism. The devastation of the war was only one condition, and not by itself a sufficient one, for the descent into the totalitarian nightmare.

Red Army demobilised

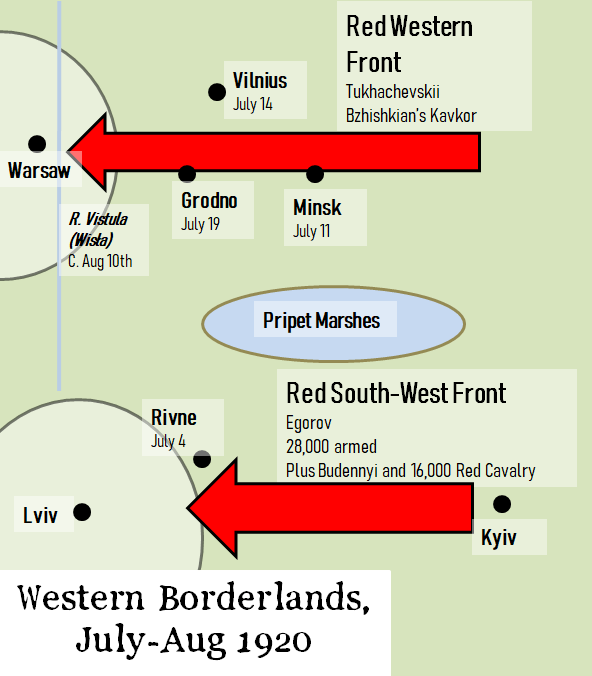

As early as the start of 1920 the Red Army started demobilizing. ‘Lenin and the majority of the party’s leadership were obsessed with the recovery of the economy,’ (not fanatical world conquest) so 90% of the Red Army was sent home. There were 5.3 million personnel in 1921 – and just 562,000 by 1924, structured as a territorial militia.

This was very much army of a new type – commanders and rank-and-file soldiers were drawn from the same social classes; their uniforms were nearly identical; ranks were abolished; revolutionary discipline forbade corporal punishment and appealed to conscience. [5]

This army was wrenched away from its egalitarian and liberatory origins – but again the rupture came in the 1930s, not in the Civil War era.

The Red Army changed radically in the Stalinist period. Ranks were reinstated. Commissars were abolished, only to return later in a more inquisitorial form. Forced collectivization stunned the rank-and-file soldiers; the Great Terror decimated and terrorized the officers. The Soviet Union entered World War Two with a severely demoralized and fundamentally changed Red Army.

Living conditions

In 1921, after fighting on several fronts throughout the Civil War, Eduard Dune returned to the factory where he had been working when he first became a Bolshevik in 1917. The place was silent and shuttered. A handful of the old workers were minding the place, living off potatoes they grew on the grounds. But on the inside, the factory was perfectly preserved in the hope of economic recovery. [6] This is an image of promised renewal and reconstruction.

The promise was fulfilled. Contrary to the clichéd fatalistic aphorisms about how socialism only ‘shares out misery more equally,’ ‘runs out of other people’s money’, etc, in the 1920s working-class people saw huge benefits. City dwellers could now avail of free healthcare and far cheaper housing. Workers had a generous social insurance scheme. The countryside was far less penetrated by new social services, but appreciated the absence of landlords. A generation of worker and peasant youth benefited from much wider access to education. Smith (Russia in Revolution, p 320 and following) emphasizes the achievements in healthcare, in spite of scarce resources.

It is significant that, as soon as the Civil War was over, economic recovery began. This backs up the idea that war conditions, not Bolshevik policies, caused economic crisis.

Soviet democracy

The regime in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War was far more pluralist than one might expect in a country utterly devastated by war. It was a rich period culturally – Soviet youth experimented with free love; nudists jumped onto trams in Moscow; Esperanto speakers organized themselves; Soviet artists were at the cutting edge globally.

Contrary to another cliché, the Communists never actually abolished workers’ control in the factories. What emerged by the end of the Civil War was a compromise (there’s that word again). Some factories were run by elected committees, others by a centrally-appointed manager (a communist, a former manager, a chief engineer, or even in some cases the former owner), others still by a worker or group of workers from the plant appointed to run it. The latter was ‘often the most successful’ arrangement. [7] In other words, where workers’ control functioned well, it was kept. Where it turned out badly (and there are many reasons it might, in a context of economic collapse and war), the state stepped in and either modified it or ended it.

In practically every ‘democratic’ country at the time, poor people, minorities and women were excluded from voting. By contrast, the Soviets were elected by all men and women over 18. Those deemed to be exploiting others were denied the vote; this amounted to a tiny percentage of people.

The Soviet regime is sometimes accused of lacking ‘checks and balances’ necessary to prevent tyranny. In 1917-18 it was nothing but checks and balances. However, it’s true that the state which emerged from the Civil War was authoritarian and dysfunctional.

The Mensheviks had by this stage positioned themselves as a loyal opposition. Lenin and his old comrade, the Menshevik leader Martov (according to Tariq Ali in The Dilemmas of Lenin) were warmly reconciled before their deaths. Nonetheless the Soviet state subjected the Mensheviks to a severe crackdown in 1921, with thousands of them arrested. There was a parallel crackdown against oppositionists inside the Communist Party – Shlyapnikov and Kollontai were not arrested, but their faction was shut down. These measures were supposed to be temporary, to be reviewed after the Soviet Union had put a few years of urgent reconstruction behind it. But as the 1920s went on the Left Opposition, which included many of the most prominent Old Bolsheviks, found itself having to campaign for a restoration of democracy, amid increasing crackdowns from the party apparatus.

Though Lenin supported the crackdown on Mensheviks and the ban on internal party factions, he sounded the alarm early about the Soviet state and, in his final writings, took a democratic turn – for example on Georgia and on cooperatives. In 1920 he cautioned: ‘ours is a workers’ state with bureaucratic distortions.’ ‘Later,’ writes Faulkner, ‘alarmed at the influence of former Tsarist officials and newly appointed careerists in the government apparatus, he posed the question: ‘This mass of bureaucrats – who is leading whom?’ [8]

The bureaucrats included the former Mensheviks Beria and Vyshinskii. Beria would later serve as the notorious head of Stalin’s secret police. Vyshinskii, as prosecutor in the Moscow show trials later in life, would call for the ‘mad dogs’ (the defendants) to be shot.

Be conscious of how much heavy lifting is being done by this word ‘later.’ Here as with other topics, the decisive break came not in the Civil War but after 1928.

We have to note, however, that with the political regime, the curve is less dramatic, the rupture less obvious. Terrible damage was done in the Civil War, and the cost of economic recovery in the 1920s was a growth of bureaucracy and ‘NEPmen’, develoments which helped Stalin’s rise to power. Faulkner writes: ‘The revolution had been hollowed out. And, in one of history’s most bitter twists, another species of counter-revolution […] was growing, a malignant embryo, inside the revolutionary regime itself.’

To be or not to be

We can’t hope to understand the Soviet Union without understanding that it was engulfed in its formative years by a cataclysm not of its making. This, alongside the country’s underdevelopment and isolation, created the authoritarian and bureaucratic tendencies, personified in Stalin, which would later seize power. So if people want to know where the Soviet Union’s siege mentality came from, they should probably read up on the siege.

We can’t hope to understand how the Soviet Union survived this cataclysm without appreciating that the October Revolution was genuinely popular.

It might be objected that if the Red soldiers could have seen the future, the cynicism and brutality of Stalinism, they would have lost the will to fight.

Maybe, maybe not. People at the time did consider the possibility of something like Stalinism; they had historical precedents in Cromwell and Bonaparte. In Victor Serge’s novel Conquered City, written in the 1930s but set during the Russian Civil War, two characters discuss the possibility that the Revolution might one day be hijacked by a dictator.

‘It wouldn’t be worth it, no…’ says Kirk. ‘It would be better, for the Revolution, to perish and leave a clear memory.’

Osipov responds: ‘No, no no, no! Get rid of those ideas, comrade. They’ve been beaten into us with billy clubs, I mean with defeats. No beautiful suicides, above all!’ [9]

I reckon western opinion of the Russian Revolution would be kinder if the revolutionaries had had the decency and good sense to be defeated and to die horrible deaths. The memory of the Soviet regime would be ‘clear.’ What’s not clear is what great service would be rendered to humanity by another epic of popular revolt and cruel defeat – another Paris Commune, Finnish Soviet, Spanish Republic, Indonesia 1965-66, or Chile 1973.

Osipov’s phrase ‘No beautiful suicides!’ brings to my mind the speech in Shakespeare’s Hamlet – ‘to be or not to be…’ In Malcolm X’s reading, the Danish prince was deciding, in that speech, whether to suffer in silence or to risk death and damnation by resistance. [10] The Russian Revolution was a moment of liberation and creativity when humble working people exercised real power. They were brave to take arms against a sea of troubles, to defend their new socialist republic by every means consistent with that end.

The Revolution lit a beacon of liberation and creativity. Revolution Under Siege set out to trace what happened to this flame. It is not surprising that the Revolution fell short of its promise. What is surprising is that even after the years of hunger, typhus, shellfire and blood, there survived still a spark emitting the light of social justice and the warmth of human solidarity.

Osipov, in the trenches before Petrograd in 1919, continues his debate with Kirk:

‘We’re here to stay, by God! to hold on, to work, to organise […] To live, that’s what the flesh-and-blood working class wants, that great collection of hungry people behind us whom we seem to be leading but who in reality are pushing us forward. Whenever there is a choice – give up or continue – they continue. Let’s continue, let’s get into the habit of living.’

References

[1] Fitzpatrick, 77-78

[2] Deutscher, Stalin, 192

[3] Smith, 383

[4] Solomon, Peter H. ‘Soviet Penal Policy, 1917-1934: A Reinterpretation.’ Slavic Review, Vol 39, No 2. Jul 1980. P 199, 202, 210.

On the Cheka being cut down, see Smith, Russia in Revolution, p 296: ‘At the end of 1921 there were 90,000 employees on the official payroll of the Cheka, but by end of 1923 only 32,152 worked in OGPU. In the same period the number of those working clandestinely for the political police fell from 60,000 to 12,900, and by late 1923 the total number in the internal troops, border guards, and escort troops had fallen from 117,000 to 78,400.’A

A note on the structure of the post-war Red Army:

In 1921 Trotsky argued for the replacement of the standing army by a territorial militia – a more traditional socialist position which had been favoured until the military emergencies of 1918. What emerged was a compromise: a small Red Army backed up by a large territorial militia. In 1934, at the height of this hybrid system, 74% of personnel were in the territorial militia. Men were drafted to serve for five years, during which time they would be soldiers for a few days a month, or a month or two in the summer. After their five years, they would be subject to recall in wartime.

[5] Reese, 40, 53-55

[6] Dune, 86-87

[7] Fitzpatrick p 80

[8] Faulkner, p 236

[9] Serge, Conquered City, p 141

[10] Malcolm X on Hamlet: https://www.openculture.com/2009/08/malcolm_x_at_oxford_1964.html