In the Name of the Working Class is an account of the Hungarian Revolution by a leading participant. The author Sándor Kopácsi was the police chief of Budapest in 1956 during the workers’ and students’ revolution. In what must have been a first for world history, Kopácsi, a high-ranking cop, came over to the side of the insurrection.

The early chapters describe Kopácsi’s own experiences as a worker and socialist fighting the Arrow Cross fascists in the 1930s and the Nazi military in the 1940s.

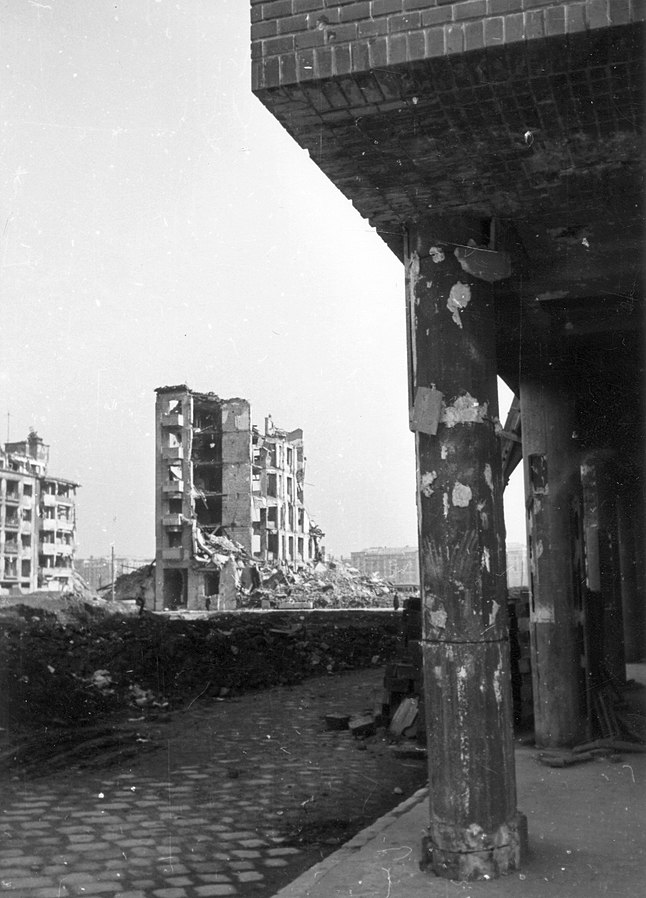

Next the book gives a vivid account of terror and mismanagement under Rakosi. The middle chapters describe the 1956 revolution, brutally cut short by the Russian invasion. The final chapters of the book are appalling. The revolution crushed under the treads of Soviet tanks, what follows is a story of imprisonment, executions and farcical trials. The reader knows that the author will survive. But for many other revolutionaries the end was a shooting in a prison yard, the sound of gunshots and screams suffocated by the roar of idling truck engines.

Portrayal of Revolution

The book contains vivid portraits of key Soviet and Hungarian figures and first-hand accounts of revolutionary events. Kopácsi witnessed the moment when crowds shoved handwritten notes through the loopholes of tanks, winning over the Russian crews inside who mutinied and joined the revolution.

It is an invaluable portrait of a revolution. He describes the government headquarters in Budapest at the height of the events. It

resembled Smolny Palace in Petrogad, the Bolsheviks’ centre in 1917, more than it did the Houses of Parliament in London… In Nagy’s anteroom, I met an old Hungarian Communist who had been one of Lenin’s personal guards soon after the Bolshevik Revolution. He said to me: ‘Kopácsi, I’ve read ten different histories of the party, each one as packed with lies as the last, and this is the first time I’ve experienced the true atmosphere of the ‘ten days that shook the world.’

-Sándor Kopácsi

I haven’t read much about the events of 1956, but the inescapable impression I got from schools and the media was that this was a liberal, pro-capitalist and nationalist uprising. That impression is thoroughly refuted by In the Name of the Working Class. This event has been misrepresented, first by the Stalinists, who said the whole thing was a fascist coup, second by the conservatives and liberals of the west.

I was somewhat aware that there was an untold story of workers’ revolution here. I read this book to look for confirmation or denial. The book confirmed it, and then turned the dial a few more notches. I found much more evidence of a working-class, democratic socialist revolution than I had expected to find.

Tragic Indecision

One major part of the story that I had never appreciated before was the indecision and resignation of Nagy and his government, including Kopácsi. It comes across powerfully in this account. During the insurrection, the cops fought the insurgents for some time before finally joining them, and Nagy did not agree to “lead” the revolution until the last minute. The revolution was really led by the workers of the heavy industries, by workers’ councils and militias. A sincere and genuine section of the ruling stratum – the likes of Nagy and Kopácsi – came over to the revolution after it was an accomplished fact.

They were sincere socialists and critics of Stalinism, brave and humanitarian individuals. But they never proved capable of anticipating or preparing for events. Theywere not as defiant or audacious as the masses or as the situation demanded. This is apparent on some level throughout Kopácsi’s memoir, but it becomes very clear in the chapters that describe the Russian invasion.

Khrushchev sends in the tanks

The USSR arranged a meeting with Hungarian delegates, ostensibly to discuss formalities associated with the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Hungary – such matters as ‘whether the departing troops should be presented with bouquets by schoolchildren’! While dragging out these petty talks, the USSR launched a full-scale invasion. Hours passed. Tanks entered Budapest and started flattening city blocks with shells. Still the talks wore on! Finally the hapless delegates were, at a certain point in the proceedings, simply arrested.

The leaders of the revolution were not idiots. On that evening, Sándor Kopácsi was fully aware of what was happening soon after the fake talks began:

’Sándor, there are troop movements. Everywhere. And these reports aren’t just coming from our observation posts, they’re from individuals, from hundreds of phone calls coming from every part of the country. Here’s a map of the invasion, drawn up from the reports.’

He spread out a map of Hungary, with multicoloured arrows, on my desk. From the reports, we knew that ten divisions were on the move in key areas of the country. At least five armoured columns were converging on Budapest…

’Has the old man [Nagy] seen the map of the invasion?’

’He has it.’

-Sándor Kopácsi

They were not idiots. But they lacked will. Nagy continued to insist on the negotiations, though it was obvious, even to him, that they were a ploy. Faced with this life-or-death crisis, key figures in the armed forces were simply advised to go to sleep for a few hours.

In a dramatic and tense section of the book, Kopácsi describes the invaders closing in. He also portrays (and defends) his own government’s failure to react. Resistance would have been futile, he tells us; he has never admired Masada. But regardless, fierce fighting raged in Budapest for days. The armed workers and youth held out heroically against the tanks. The police chief went to the government HQ, where an enormous phalanx of Hungarian tanks awaited the approaching Soviet forces. But there was to be no battle: Kopácsi convinced the tank crews to lay down their arms and surrender without a fight.

Kopácsi, in my view, fails to justify this fatalistic and irresolute attitude. When we look at how fierce the fighting was in the end, and we tally up the missed opportunities, the toll of lost initiative, the military assets surrendered without a fight, we get the impression that a far more organised and resolute defence of Budapest could have been mounted and could have been successful. The Soviet Union was powerful, but not omnipotent. They had to take into account the willingness of their own soldiers and population to fight, and the global context of the Cold War. Every day and every hour counted. I have not read widely on the subject. But based on the information in this book, it seems to me that a few more days’ stiff resistance might have forced the Stalinists to back off and come to terms.

After this disaster, there followed for Kopácsi years in prison, listening to the gunshots outside the walls as his comrades were mowed down. It was worse than any Masada. His desire to avoid needless bloodshed is sympathetic on a human level (though it was a disaster politically, historically), and he did not know that such a massacre would follow surrender.

The title of this memoir is entirely sincere. Kopácsi wrote it as a refugee in Canada, still a true believer in socialism. It is absolutely compelling, and for the experiences and lessons recorded in it, worth its weight in gold.