In Part One we began a critical look at James Connolly’s claim that Gaelic Irish society was basically socialist. We focused on the period from about 800 to the late 12th Century, and in particular on the question of kingship.

We have seen that Irish kings were elected from a wide pool of candidates and by a wide electorate; that they were neither sacred nor above the law, and that the people were their clients and electors, not their subjects. In short, they don’t look much like our traditional idea of kings and appear more like elected officials or public servants.

Today we’re going to look at warfare and hospitality, two very different subjects that both tell us a lot about kingship and Irish society in the early Middle Ages.

So far, so wholesome. But before we begin….

A word of warning

We are not here to romanticise Gaelic Ireland. I have little patience for ‘noble savage’ or ‘Fremen mirage’ tropes. No pre-modern society presents us with a tradition which modern people can or should attempt to copy. I’m also impatient with claims that the way X or Y people lived two hundred or even two thousand years ago was a more ‘authentic’ or ‘organic’ way of life than modernity. A lot of commentators like to put nationalities or religions (or even points of the compass like ‘The West’) in separate boxes, as if they were or factions in a videogame. For centuries every scholar pretended that there was some essential continuity between the Germans of Tacitus and modern German people.

Sometimes this kind of thing is flattering and romanticising. Other times it’s meant as an insult. Either way it’s annoying. A few years ago an Irish journalist said that the French president was only unpopular because French people have something written into their culture that makes them want to cut the heads off authority figures. Or the whole trope of saying that there’s some line of continuity from 7th century Irish monks writing their manuscripts all the way to James Joyce. I don’t like this kind of thing – broad national stereotypes projected into periods where they don’t even apply.

So let’s not come at Gaelic Ireland from that kind of angle.

In most countries, go back even three hundred years and 90%+ of the folks you’d meet would be illiterate toiling people confined to small rural communities. In their daily lives, ambitions and morality they would be very different from any modern person. If the past is another country, then the pre-industrial, pre-Enlightenment past is another planet.

Even if, somehow, there existed some utopia in amid all the scarcity and violence and narrow horizons of the pre-industrial past, we couldn’t bring it back. And if modern people could dismantle modernity and return to that past, they would find they don’t like having to make every stitch of clothing by hand, or sleeping in a dim close hall with ten other people and a few cows and dogs, able to hear every fart and snore; or toiling away at crops and livestock for your entire life, never more than a few steps away from ruin.

It’s important to start with these sobering thoughts, because last week and again this week the focus is on the more egalitarian features of Gaelic Ireland. A lot of people, me included, find this stuff appealing. But as we touched on last week, Gaelic Irish society also had features that modern eyes would find hideous – features which challenge Connolly’s assertion that this society was ‘as Socialistic as the industrial development of their time required.’ Part 3 will deal with this sinister stuff more fully, and draw some conclusions from it.

If you want to get an email update when Part 3 goes up, subscribe – drop your email into the box below.

‘Those who make war’

Warfare was generally of a low intensity in Gaelic Ireland – raids, skirmishes, cattle theft. There was no warrior class and there were no housecarles or king’s bodyguards. There was no fyrd or militia, no custom of holding land in exchange for military service and no landless professional warriors.[i] A king did not have the means to maintain armed forces at his own expense, and billeting them on his people or on allies was politically fraught; he could do it, but it was a great way to lose friends and resources.[ii]

The only armed forces he could call upon were his electors. It was the duty of all free and able members of the tuath (people, territory or petty kingdom) to carry arms, and they assembled and fought only for limited periods.[iii]

By contrast, the nobles of medieval Europe had war at the heart of their identity. Knights were a special class elevated above the others. They held their land in exchange for an oath that they would fight. When contemporary writers chose just one word to describe the nobility, bellatores was the word they used – ‘those who make war.’[iv] But the Irish flaith (nobles/officials) were not a warrior class. In fact, I’m not sure they were even a class full stop.

The Irish king had no armed force loyal to himself. His armed forces were the same people who had a duty to depose him if he should fail in his duties. Military leadership was only one criterion, and not the foremost, on which contemporary sources judged kings; it was more important that they be wise, generous, cheerful, sound judges of disputes, etc.

War… War actually does change

Like a lot of things, this changed later in the period under discussion.

The Normans arrived from 1169 or so, with their ruthless hierarchies of knights and lords and their castles and their armies of knights and archers. Then came the gallóglaigh (foreign soldiers, often anglicised as ‘gallowglasses’), heavy infantry fighters from the Isles of Scotland who came to Ireland from the 13th Century on and revolutionised warfare.

From this point on Gaelic Irish kings tended to become more like lords and less like elected chiefs. As Simms writes in From Kings to Warlords: ‘A leader whose military strength was based on a professional army rather than on a hosting of his own free subjects had little need to consult the wishes of those subjects, except the half-dozen or so chief vassals who, like himself, controlled hired troops.’ Elections became a formality.[v]

This is why I chose the late 12th Century as a cut-off point. From here on Ireland is a country under conquest. Those natives who do not bend the knee adapt to the presence of the conquerors.

But even before the Normans and gallóglaigh, things were changing. My intuitive guess would be that the gallóglaigh came as a response to changes in Ireland; suddenly there was a market for mercenaries in Ireland. Why? Because from around 1000, beginning with Brian Boru, provincial kings arrogated more power from the rí tuaithe to themselves. As we noted last week, they fielded greater armies for longer periods, built fleets and fortresses, and placed heavier burdens on the people to pay for it all. They enjoyed the revenues of Scandinavian ports like Dublin and Limerick (which means they made a mint on the slave trade – of which, more next week). They billeted troops on their ‘allies,’ who no longer dared to resist or to complain. From around this time, people tended to start calling the rí tuath (petty king) a taoiseach (chief), reflecting a loss of status and sovereignty.

The social order in Ireland was changing even before the conquest. The kings and flaiths were developing into an unaccountable ruling class with a monopoly on violence. But they were still a long way off. These changes had not yet added up to a total transformation.

Hospitality

O’Sullivan’s Hospitality in Medieval Ireland is a fascinating read. All pre-modern societies placed an emphasis on hospitality but Gaelic Ireland went further. Every ‘free law-abiding Irishman’ was entitled to entertainment and a night’s lodging.[vi] Everyone above the rank of ócaire (a humble farmer) was obliged to host. ‘Expulsion’ or ‘Refusal’ of a guest was a civil crime. To provide uncomfortable lodgings or bad food left the host open to the dreaded satire of the poets. Generosity was a solemn precondition for kingship: ‘the Old Irish gnomic text Tecosca Cormac maintains that the most shameful thing a king could do was give a banquet without brewing beer.’[vii]

I believe this custom was an extension of the king’s obligation to redistribute wealth. Each farmer or artisan having their own specialisation and limited means of exchange, the role of the king or flaith, the reason such official positions existed, was to receive and redistribute the various products.[viii]

Receiving and redistributing could take many forms, including tributes, gifts and the king’s many obligations to his tuath: maintenance of roads, bridges, ferries, common mills and common fishing-nets; and the cumal senorba, the portion of the common property that was set aside for the elderly, the disabled and the sick.

One of the key signs that kings and chiefs were getting more arrogant later in this period, and more decisively after the Norman conquest, is that their demands in terms of billeting and the annual ‘coshering circuit’ grew heavy – less of the redistribution, more of the extraction. These demands were necessary to keep up the kind of relentless military campaigns, year after year, that the 11th and 12th century provincial kings engaged in.

Hospitality was a natural extension of a king’s obligations. A satire on an inhospitable king was not simply a condemnation of his personal stinginess. It was a political attack; the king in question had neglected his duties as surely as if he had fled from battle or allowed a bridge to fall into disrepair.

Brett Devereux’s blog explains the role of nobles or ‘big men’ in agrarian societies the world over and how they helped to redistribute the surplus (although on terms that benefited themselves more than anyone else). So this is by no means confined to Ireland. But my argument is that the Irish king did a hell of a lot more of the redistributing and a lot less of the fighting compared to nobles in England and further afield. Redistribution was so central to the role of Irish kings that flaithiúl, ‘lordly,’ remains the modern Irish word for ‘generous’ – which is a long way from bellatores.

Gods without notions

To round off this week’s post, let’s look at two Irish legends that were popular around this period and that shed some more light on the question of hospitality. Of course, these are fictional stories told in a culture that took delight in the most extravagant exaggeration. But these are the stories that the people (or more cynically, the powerful patrons of culture) wanted to hear. They tell us a lot about people’s expectations and values.

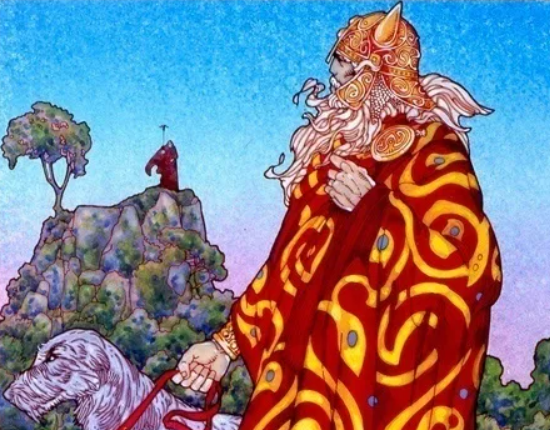

Dagda was a god; people sometimes say that he was the Irish equivalent of Zeus or Odin but I don’t buy that (for reasons I’ll touch on below).

Cridenbel, ‘an idle blind man,’ used to ask for part of Dagda’s food every day:

‘For the sake of your good name let the three best bits of your share be given to me.’

It would have been dishonourable for Dagda to refuse, so every day he parted with most of his dinner. At this time Dagda was working at digging ditches and building raths (fortified households) so he had quite an appetite. Deprived of one-third of his food every day, he began to starve. But there was no way out of this sticky situation; it was better to starve than to refuse a request. At last Dagda’s son Angus Óg came up with a clever plan. Dagda put three pieces of gold on his plate and, when Cridenbel asked for the ‘three best bits’ of the meal, Dagda gave him the pieces of gold to eat. ‘And no sooner had Cridenbel swallowed down the gold than he died.’[ix]

Another story, related in O’Sullivan’s book, told of a kind one-eyed king who would never refuse anyone anything. A poet who was his guest decided to test his kindness. He asked the king to give him his eye for a gift. The king had no choice but to hand it over, leaving the poet with three eyes and himself with a total of none.

These stories reflect social mores. In them, hospitality is an obligation, not a gift. It is less dishonourable for Dagda to murder Cridenbel (!) than to refuse any request he might make.

In a call-back to points in Part 1 about how Irish kings could be deposed, note that the incident with Cridenbel and Dagda occurs in a context of austerity, brought about by the stinginess of King Bres. Though Bres is not without merit as a king (he is easy on the eyes), his lack of generosity is not long tolerated; the people overthrow him and drive him out of Ireland.

(While we’re at it, let’s take a slightly closer look at Dagda. In other stories we see him unable to restrain his appetites: eating and drinking until he vomits and passes out; going on an important mission only to be seduced by two different women; falling on his bare arse and staggering about with his ‘enormous penis’ trailing on the ground.[x] He’s more of a pintsman than a patriarch of Olympus. Irish kings were less exalted than kings elsewhere, and the same goes for Irish gods.)

Until next time…

Again, so far so wholesome, apart from the blinding, murder and binge drinking. When we look at the period between 800 and 1200, there’s actually a lot of evidence for the claim that an Irish king was something like a public servant.

However, we have only established that the king was a public servant in relation to the free heads of household – presumably men – of the tuath. What about women? What about the unfree, the slaves? Next week’s post will address these questions, adding plenty of darker shades to our picture of Gaelic society.

[i] Hayes-McCoy, GA. Irish Battles: A Military History of Ireland, Gill & Macmillan 1969 (1980), p 48

[ii] O’Sullivan, Catherine Marie. Hospitality in Medieval Ireland 900-1500, Four Courts Press, 2004, p 50-51

[iii] Jaski, Bart. Early Irish Kingship and Succession, Four Courts Press, 2000. p 99

[iv] Bishop Adalbero of Laon famously summed up the nobility, clergy and peasants as bellatores, oratores et laboratores -those who fight, those who pray and those who work. ‘Adelbero Ascelin’ in World Heritage Encyclopedia, Project Gutenberg, http://self.gutenberg.org/articles/Adalbero_Ascelin, accessed 17 May 2021

[v] Simms, Katharine, From Kings to Warlords, The Boydell Press, 1987 (2000), pp 19-20

[vi] O’Sullivan, p 31

[vii] O’Sullivan, 32, 87

[viii] Woolf sums this up as ‘the practise of redistributive chieftaincy that characterised the Irish political system.’ Woolf, Alex. ‘The Scandinavian Intervention’ in Smyth, Brendan (ed), The Cambridge History of Ireland, Cambridge University Press, 2018, p. 117.

[ix] Gregory, Augusta. Gods and Fighting Men, Colin Smythe Limited, 1904 (1970), 32-33

[x] The detail about Dagda’s member comes from The Silver Arm (Butler Sims (1981, 1983) written and illustrated by Jim Fitzpatrick, Ed. Pat Vincent. P 65. I don’t recall coming across that particular detail in Gregory’s book.