Listen to this post on Youtube or as a podcast

In Stephen King’s novel The Stand two new societies emerge in a post-apocalyptic USA, based on opposite sides of the Rocky Mountains. A democratic society takes shape in Boulder, Colorado. Meanwhile in Las Vegas power is seized by a supernatural madman who punishes drug users with crucifixion. Only one of these two regimes can survive.

That great, flawed horror epic comes to mind because this post is about two distinct White regimes which emerged on either side of the Ural Mountains in Russia in 1918, and how one consumed the other. As we saw in Part 5, the Czech Revolt led to dozens of White-Guard governments popping up. The Right Socialist Revolutionary (SR) party set up a regime called Komuch (the Committee of Members of the Constituent Assembly) based in the Volga town of Samara. They wanted a republican, democratic counter-revolution, with a mandate from the Constituent Assembly and all the ‘t’s crossed and the ‘i’s dotted. Meanwhile across the mountains a faction of officers and Cossacks set up the Provisional Siberian Government at Omsk, a military dictatorship with a thin Siberian Regionalist veneer.

The most important difference was that Samara was anti-landlord and Omsk was pro-landlord. They were at loggerheads on the land question.

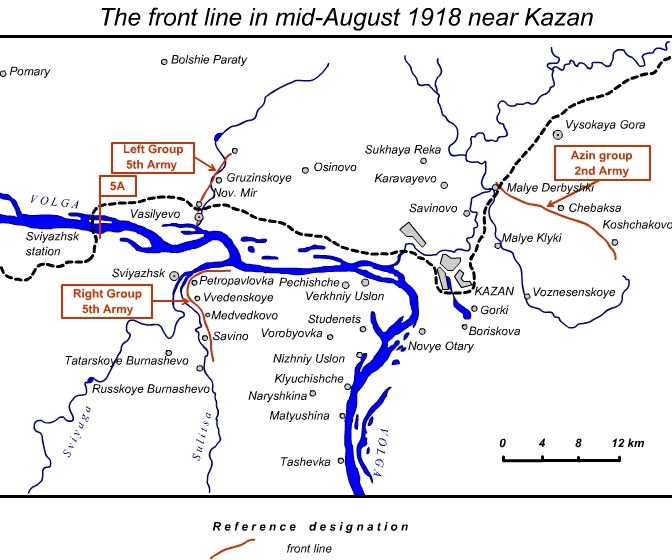

These two regimes did not use direct violence against one another – until the very end, when the outcome was no longer in any doubt. They were supposed to be on the same side against the Reds. But relations were tense; Omsk boycotted Samara’s manufactured goods, and Samara boycotted the grain of Siberia.[i] In August the Omsk regime shut down the Siberian Regional Duma – an elected body dominated by Right SRs, of which the Omsk regime itself was an ungrateful child. Komuch was never secure even within its own territory: ‘Russian officers as well as business and middle-class circles much preferred the state-conscious anti-Communism of Omsk.’[ii] And that territory was shrinking. In a strange twist of fate, the military men of Omsk resided safely a thousand miles in the rear while the Right SRs – civilian politicians – led the regime that was actually fighting the Reds on the Volga. From early September that fight was going very badly. As we saw in Part 8, Kazan and Simbirsk had fallen, and this had thrown Komuch into crisis.

Omsk

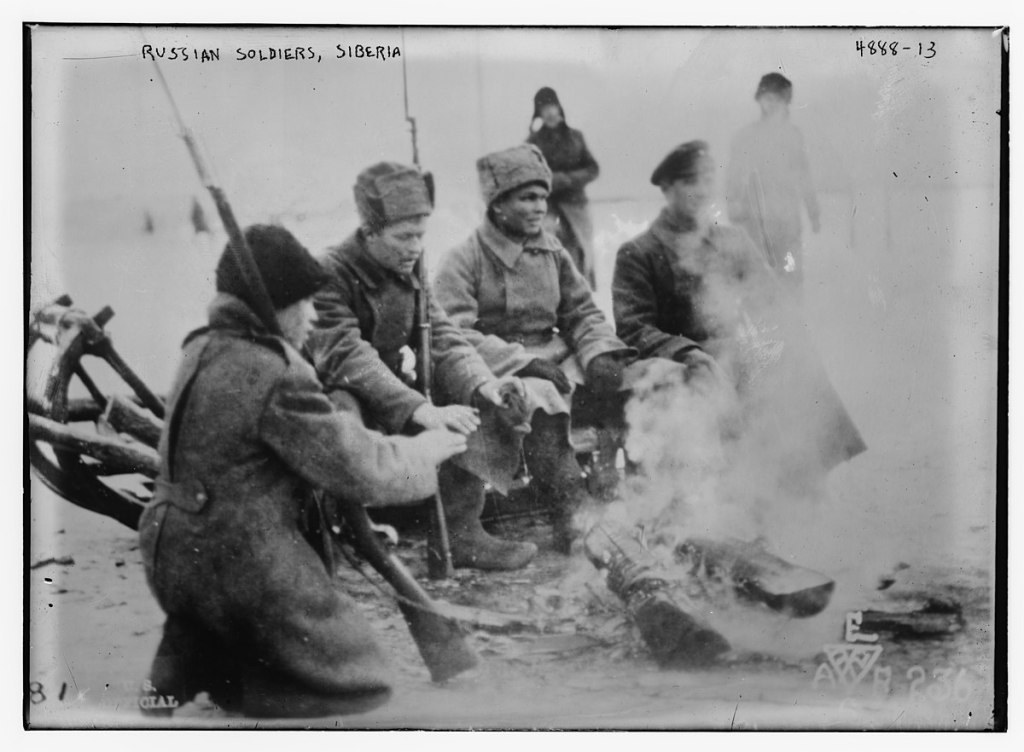

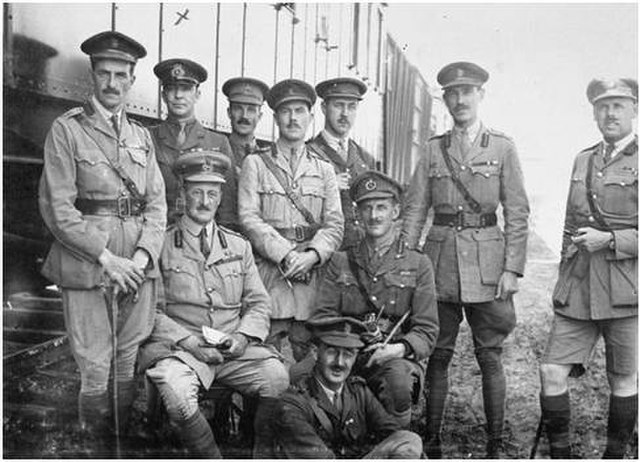

While Komuch had grown weaker, the Provisional Siberian Government had grown stronger. The Omsk government did not rest on popular support. Its political wing consisted of junior government officials, conservative refugees from central Russia and the Siberian Regionalists. Its military wing consisted of officers and Cossacks, assisted by a battalion of British soldiers from the Middlesex Regiment. This military wing had built itself up to a force of 38,000 by September, poaching officers from Komuch instead of helping them in any serious way.

The ‘Novoselov Affair’ of September 1918 manifested something that had been obvious for some time. The Siberian Regionalists wanted to increase their presence in cabinet, and a politician named Novoselov was their chosen candidate. But he was abducted by Cossacks and murdered. It was a clear signal, Smele suggests, that anyone who tried to challenge the officers and Cossacks would be found dead some fine morning by the banks of the Irtysh River.

The western Allies looked on with impatience, and demanded Komuch and Omsk get their act together and present a united front. The result was the state conference at Ufa on September 23rd 1918. Ufa is a mountain town half-way between republican Samara and military Omsk. It was as if Stephen King’s two post-apocalyptic tribes held a conference somewhere in Utah. At the Ufa (not Utah) conference a wide array of different counter-revolutionary governments came together. Intellectuals, ‘moderate socialists’ and former terrorists sat down to discuss cooperation with Black-Hundred generals, foreign agents and Cossacks.

Chernov

The centre of gravity within the SRs had swung from the Right to the Centre. This Centre was embodied in Viktor Chernov, the leading figure in the party, a stout man with a powerful presence who had served as Minister for Agriculture under Kerensky in 1917. During the few hours’ life span of the Constituent Assembly, the deputies had elected him president of Russia. Unlike most Right SRs, he had actually criticised the policy of coalition with the right during the year 1917, though like the others he had dragged his feet on land reform. In the view of his supporters, the October Revolution had vindicated his criticisms; in the view of the officers, he was largely responsible for ‘the weak and indecisive policy that led to the downfall of Mr Kerensky’s government.’[iii]

Now, along with others, he had arrived in Komuch territory arguing for the Right SRs to take a hard line at the Ufa conference. He was up against the resistance not only of officers and Cossacks but of many in his own party. The historian Radkey writes that many Right SRs had become ‘fervent patriots, partisans of the Entente, and devotees of the cult of the state.’ By 1917 ‘a large segment of the Populist intelligentsia had become [Constitutional Democrats] without admitting it.’[iv] We have already seen how the Left SRs split from the party in disgust at these developments. But the divisions ran deeper still. Even Chernov’s centre was divided into a right centre and a left centre. Chernov himself was prevented from going to Ufa by his own comrades, in case his presence upset the Omsk faction.

The Ufa conference opened with a religious service, then talks began. The numbers of delegates heavily favoured the left, but the various factions all had veto power, tipping the balance back to the right. On the other hand, the need to keep the Czechs happy and to impress the Allies put a certain weight on the scale for the left. Countering this in turn was the real balance of forces between Samara and Omsk, which worsened for Samara every day as the Reds advanced.

One sore point was the Constituent Assembly. The Right SRs insisted that it was the only legitimate state power in Russia, sanctioned by the elections of December 1917. Omsk refused to recognise this body, ‘elected in the days of madness and made up chiefly of the anarchist element.’[v] It appears the Omsk officers believed no election could be considered valid until half the Russian working class was dead or behind barbed wire, and until a knout-wielding Cossack could be placed next to every polling station to glower at the voters. An election held in conditions where the workers were organised and confident could not be considered legitimate in their eyes.

It could be argued that Samara won this round. The Omsk government accepted the legitimacy of the Constituent Assembly in principle. But they would not allow it to assume power until January 1919 at the earliest, and even then it must assemble a quorum of 250 elected deputies. To assemble such a quorum, in the chaos of Russia in 1918, was impossible; it had taken Chernov months to make his way to Samara. So it was a hollow victory for Komuch; the generals’ ‘recognition’ was meaningless.

The Ufa Directorate

The outcome of the conference was a merger of Samara, Omsk and other statelets into a government called the Ufa Directorate. Its programme: abolish the Soviets; return lost territories to Russia; resume the war against Germany; and set up a democratic regime.[vi] The Right SRs also changed their land policy to favour the White landlords with whom they were making a deal.[vii]

On paper, the five-member Directorate had a Socialist majority – a concession to the Czechoslovak Legion, who were increasingly war-weary and cynical of the rightward trajectory in the White camp.

But this was only on paper. Just two of the five members of the Directory were SRs, and they were the two most conservative and least authoritative SRs who could be found. The other member of the Directorate with ‘Socialist’ credentials was Tchaikovsky, who was safely in the Arctic Circle at the time, performing socialist fig-leaf duty for another White government.

The Right SR Central Committee had previously voted 6:2 in favour of Chernov’s position that the SRs should fight against ‘the left-wing Red dictatorship [and] an equally despotic Right-wing White dictatorship’ that would probably emerge. ‘In order to fulfil its historic role,’ the party ‘must emerge as a Third Force and fight a determined war for democracy on two fronts.’[viii]

But the same Central Committee flew in the face of this resolution when it voted 4:3 in favour of the Ufa agreement.

Toward the climax of The Stand, that compelling and problematic 1978 horror novel, the democrats from Boulder go to confront the dictator at Las Vegas. They are armed only with their own courage and moral rectitude, along with a mandate from a supernatural higher power.

You can read the book yourself to find out how this plan works out for them. But you only need to read on another few paragraphs to find out how the same method worked out for the SRs when they entered the Ufa Directorate.

If the comparison seems far-fetched, consider these words by the Right SR Avksentiev: ‘We must put our head in the lion’s mouth. Either it will eat us, or it will choke on us.’[ix]

Life in the lion’s mouth was not comfortable. The officers resented what little influence the Right SRs had in the Directorate . In their view, Chernov was whispering in their ears urging them to set up democratic soldiers’ committees inside the White Army. In fact Chernov was not supported by a majority on his Central Committee, let alone by Avksentiev. But he was the bogeyman conjured up by the ‘Siberians’ to add colour to the implausible assertion that the Directorate was dominated by elements who were only two steps away from Bolshevism. ‘The name ‘socialist’ was for them synonymous with ‘traitor.’’[xiii]

‘I drink to dead Samara!’

Meanwhile the Reds were advancing across Komuch’s territory.

The 6,000 workers of Ivashchenko near Samara rose up against the Whites. But this rising was premature; Komuch still had enough strength to put down the rising, killing 1,500.[x] The officers of the People’s Army went from village to village conscripting the peasants. They used the old tried-and-tested Tsarist recruitment methods: public floggings and violent reprisals for deserters and their families.

But they were not so bold in early October, when the Red Armies closed in on Samara. The White volunteers were too few to defend the town. The Czechs retired without a fight. The peasant conscripts deserted to the Reds. The Cossack Dutov withheld any aid. Nobody would defend Samara, but it gets worse; no-one could be found to organise its evacuation. It was a rout, everyone for himself (Chernov included) crowding onto trains to get away.

An SR leader named Volsky was reportedly found drunk and despairing, smashing glasses and ranting: ‘I drink to dead Samara! Can’t you smell the corpse?’

Czech officers taunted Constituent Assembly deputies: ‘Where’s your Army?’ ‘Government? You the government?’

As Samara fell to the Reds, Komuch lashed out at its Red prisoners, killing 306 of them.

In spite of its name the Ufa Directorate spent most of its existence governing from railway cars, and officially moved to Omsk in early October. The Novoselov Affair had demonstrated that no civilian politician should push their luck in Omsk, where drunken officers still sang ‘God Save the Tsar.’ The Council of Ministers which served under the Directory was dominated by people more associated with Omsk than Samara. In that city the SR politicians felt the same sense of insecurity and isolation that they had felt in Petrograd in 1917, and in the words of Serge, ‘The very same illusions fortify their spirits. The vocation of parliamentary martyr rises in their breasts.’[xi] Think of Avksentiev with his head in the lion’s mouth. I don’t know what they were thinking; that if they did everything by the book, hosts of constitutional angels would come to their aid… Or that they would get their reward in parliamentary heaven.

Why all the hostility between Samara and Omsk? One way of looking at it is that the generals were too stubborn to recognise that the Right SRs could be a useful political fig-leaf for their cause. They could have kept many Right SR leaders on side by making a few superficial concessions. Their association with the Right SRs was used at the time and is still used today to claim democratic credentials they did nothing to deserve. But the other way of looking at it is that the generals were sophisticated enough to realise that the Right SRs were of little use even as fig-leaves. The Right SRs had only a very narrow base in 1918; their most reliable supporters were the Czechoslovak Legion. Their electoral mandate, such a powerful instrument in constitutional politics, might have been expected to translate into something impressive in the language of civil war. But it simply did not translate.

The Bolsheviks were wise not to recognise the authority of the Constituent Assembly – because practically no-one else did.

Two devastating scenes remained to be played out in the tragedy of the Right SRs. Their protagonist was Admiral Alexander Kolchak.

The Council of the Supreme Ruler

Alexander Kolchak arrived in Omsk in mid-October and was given the Ministry of War and the Marine.

Kolchak was a naval officer from a well-off military family. He explored the Arctic Circle in 1903, travelling by dog-sleigh and spending 42 nights on the open sea. After the disaster of the Russo-Japanese war he approached the Duma (the rigged Tsarist parliament) with plans for naval reform. During World War One he served as an admiral first on the Baltic and then on the Black Sea. During the Revolution, he defied a sailors’ committee by throwing his sword into the sea and declaring the men unworthy of him. ‘Many organisations and newspapers with a nationalist tendency spoke of him as a future dictator.’[xiv]

He spent a long time abroad on various wartime plans and projects with the US and other Allies which came to nought. He became an agent of the British state, and was called by London ‘the best Russian for our purposes in the Far East.’[xv] He returned to Russia with the Japanese invasion forces and tried to organise armed detachments in Manchuria and the Far East. Thence he came to Omsk.

A conspiracy coalesced around him, with or just-about-possibly without his knowledge. According to one of his comrades, he ‘had no part in the plot, but was in favour of a military dictatorship.’[xvi]

He had just returned from a tour of the front when it all kicked off. On the night of November 17th, a Cossack detachment arrested many Right SRs, including the two members of the Directorate. The Council of Ministers assumed power. There was a battalion of the British Middlesex Regiment stationed in Omsk at the time, and their leader General Knox knew about the coup before the event and did nothing because he hated the Directorate and was a ‘great champion’ of Kolchak.[xvii] The Omsk garrison commander was on board too. It was a clean sweep.

The Czechs were appalled; but the French and the British dissuaded them from taking any action, the French verbally and the British by physically defending the conspirators. So the coup was bloodless. A new power took over, calling itself the Council of the Supreme Ruler.

The ministers offered the vacant position of Supreme Ruler to Kolchak. He accepted the position, it appears, with a heavy heart, refusing it on the first offer.

Apologists for the coup preferred not to use the word. It was simply ‘the change;’ one regime ‘gave place’ to another; ‘the directorate ceased to function, and its place was taken by Admiral Kolchak and his ministry,’ who ‘[took] the authority… into their own hands.’ It had been necessary, because the Right SRs had prepared the ground for the Bolsheviks in October 1917, and ‘The same fate now threatened the Directorate.’[xviii]

The Komuch deputies were holding a congress in the mountain town of Yekaterinburg when news arrived of the coup – news, soon followed by armed bands of Siberian Whites who surrounded the venue and arrested them all. The Czechoslovak general Gajda saved them from being murdered by taking them into his custody. There was one last attempt to raise the banner of Komuch with yet another congress, this time in Ufa on December 2nd. It was shut down by Kolchak’s men.

Alone and on the run, Chernov decided to propose a deal to the Reds. They would have the support of the Right SRs if they would only recognise the Constituent Assembly. Still he clung to it. And why wouldn’t he? With it, he was president of Russia. Without it, he was an isolated politician alone on the run.

The Right SRs were legalised – not due to Chernov’s efforts, and needless to say the Constituent Assembly was not recognised. Chernov went to Moscow where he lived in hiding for a year or so before leaving Russia forever.

Back in Siberia, meanwhile, the Regionalist tradition was openly discarded in favour of old-fashioned Russian chauvinism.[xix]

The lion had closed its jaws and, without choking, swallowed the head of the Right SRs. Chernov blamed his own party: ‘our comrades were among those who helped Kolchak’s dictatorship to happen. They pulled down the bulwark of democracy with their own hands.’[xx]

Kolchak had emerged as one of the two paramount leaders of the White cause. In Spring 1919 the Allies would recognise him as superior to Denikin. He was ‘Supreme Ruler’ and not ‘dictator,’ says Smele, ‘so as to maintain the decorum of the civic spirit.’

The note Kolchak struck in his first major address to the Russian people should be familiar to anyone acquainted with Denikin and his ‘I am not a politician, just a simple soldier’ routine:

I am not about to take the road of reaction or of disastrous party politics, but my chief aim will be the creation of a fighting army, victory over the Bolsheviki, and the establishment of justice and order so that the nation may without interference choose for itself the form of government that it desires.[xxi]

The Stand

Joshua Rossett, an aid official from the United States, gives an insight into the perspective on Kolchak held by many in the Pacific port of Vladivostok. He paints a picture of the intelligentsia, workers, peasants and well-meaning Americans all working hard to deal with humanitarian problems, united under the zemstvo, or local government. Then comes the shock of the Omsk coup. He describes Omsk, and the Ufa Directorate which preceded it, as a coup by food hoarders.

At the last local elections in Vladivostok, 35,000 votes were cast. A commissar came down from Omsk and began striking names off the voter rolls, eventually leaving only 4,000 – whom Rossett says were monarchists and speculators.

Rossett had a more visceral shock when local authorities asked a Russian cavalry officer to provide escort for 600 prisoners – men, women and children, mostly Red, some criminals. They were infected with typhus and had to be moved into quarantine. The officer at first refused, then then ‘with genuine enthusiasm’ offered to kill them all.

Very soon there was resistance to the new regime – not from civic-minded people angry at Kolchak’s disregard for the Constituent Assembly, or from appalled American aid workers, but from peasants. They deserted from the White army, refused to supply food, resisted the return of old landlords and old Tsarist officials. The hand of the Supreme Ruler came down heavy on them with hundreds of townships bombarded or burned and peasants ‘shot in dozens.’[xxii] The Red workers had long since fled from White rule in their home towns and set up guerrilla armies in the endless forests of Siberia. Now they were joined by masses of peasants.

The guerrillas composed songs about the untouched forest that sheltered them: ‘Sombre taiga, danger-ridden, Massed, impenetrable trees! Yet we rebels, safely hidden in thy glades, found rest and ease.’[xxiii]

Soon resistance flared up right at the heart of Kolchak’s power. The last scene in the tragedy of Komuch was the December revolt in Omsk. Communists based in the city led a workers’ uprising against the Supreme Ruler. It was crushed, and in response Kolchak lashed out indiscriminately to his left. Serge says that 900 were killed in the repression. Many of the remaining Right SRs and Mensheviks, who had taken no part in the uprising, were included in the massacre. Mawdsley writes: ‘Prominent SRs, including several Constituent Assembly delegates, were summarily executed.’ Of those who were lucky enough to get away, many went over to the Reds. The less lucky survivors sat huddled in cold dungeons, shoulder-to-shoulder with the Communists as 1918, the year of Komuch, withered and died.

Consolidation

The Russian Civil War is so chaotic and confused that when, from time to time, a pattern emerges in the whirlwind of events, we should pause and examine it. In the White camp over the course of 1918 we can trace the following pattern:

- Step 1: Foreign Intervention

- On the river Don in May 1918, the Germans intervened.

- On the river Volga in May 1918, the Czechs intervened.

- Step 2: Local revolt with a ‘democratic’ flavour

- Aided by the Germans, the Don Cossacks rose up against the Reds and established a state.

- Aided by the Czechs, the Right SRs rose up against the Reds and established a state.

- Step 3: In the shelter of the revolt, reactionary forces coalesce

- Behind the shelter provided by the Germans and the Don Cossack state, there arose a military dictatorship of officers and Kuban Cossacks.

- Behind the shelter provided by the Czechs and the Right SR state, there arose a military dictatorship of officers and Siberian Cossacks.

- Step 4: Tensions between democratic and reactionary wings

- Nonetheless the Don Cossacks were on unfriendly terms with the Volunteer Army, and the Right SRs were on unfriendly terms with the Omsk regime.

- Step 5: Reactionary wing defeats democratic wing

- The Don Cossacks spent their strength at Tsaritsyn, then their remains (as we will see in future posts) were cannibalised by the Volunteer Army.

- The Right SRs spent their strength at Kazan, then their remains (as we have just seen) were cannibalised by the Omsk regime.

The parallels should be noted well because in them we can see the complex mess of factions tending to resolve itself into united and powerful White armies. Cossack autonomy, Siberian regionalism and Democratic Counter-Revolution – transitional forms, gateway drugs – fall by the wayside and everywhere the White cause takes the form of a far-right military dictatorship.

[i] Mawdsley, Evan. The Russian Civil War, p 145

[ii] Pereira, NGO. ‘The Idea of Siberian Regionalism in late Imperial and Revolutionary Russia.’ Russian History, vol. 20, no. 1/4, Brill, 1993, pp. 163–78, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24657293.

[iii] Bechhofer, CE. ‘What happened in Omsk? Admiral Kolchak’s Credentials.’ Current History, Vol 10, no. 3, pt 1, June 1919, 484-485. Accessed on Jstor.org https://www.jstor.org/stable/45324453?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

[iv] Pereira

[v] I copied and pasted this quote word-for-word from a reliable source – but I can’t remember which one! When I find it again (probably as I comb through my notes in search of something completely different six months from now), I will post a proper citation here.

[vi] Serge, Victor. Year One of the Russian Revolution, p 346

[vii] Smith, SA. Russia in Revolution, p 169

[viii] Trapeznik, Alexander. The Revolutionary Career of Viktor Mikhailovich Chernov (1873-1952). Masters’ thesis, University of Tasmania, 1988, p 283

[ix] Smele, Jonathan. The ‘Russian’ Civil Wars, p 74

[x] Serge, Year One 344

[xi] Serge, Year One, p 377

[xii] Mawdsley, 153

[xiii] M. I. Smirnov. “Admiral Kolchak.” The Slavonic and East European Review, vol. 11, no. 32, Modern Humanities Research Association, 1933, pp. 373–87, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4202781.

[xiv] Smirnov

[xv] Smele, 291

[xvi] Smirnov

[xvii] Smith, p 170

[xviii] Bechhofer

[xix] Pereira

[xx] Trapeznik, p 285

[xxi] Bechhofer

[xxii] Serge, Year One, p 378

[xxiii] Wollenberg, The Red Army, Ch 2 https://www.marxists.org/history/ussr/government/red-army/1937/wollenberg-red-army/ch02.htm