Nkrumah and the Ghana Revolution by CLR James

Motive Books, 1977 (1962)

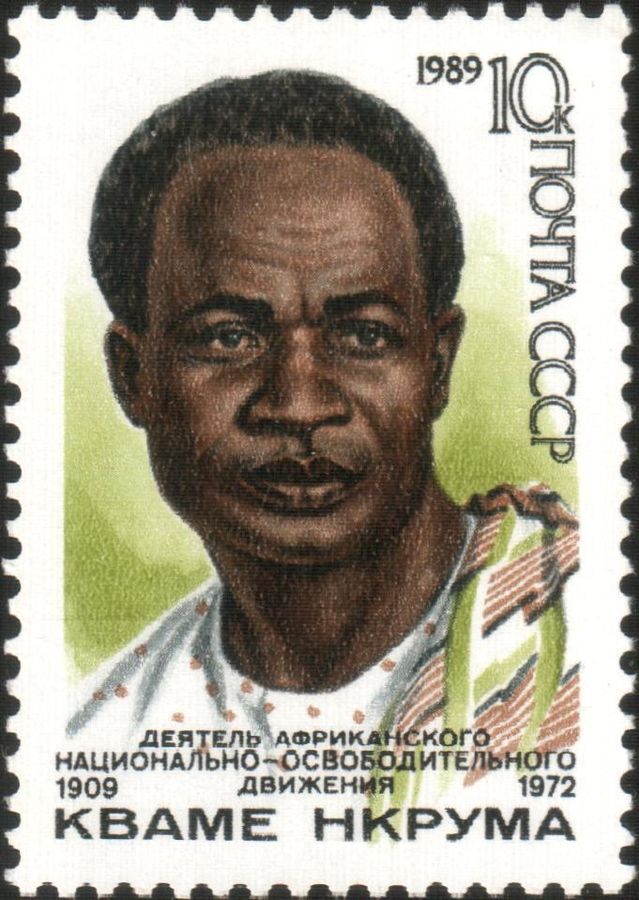

Kwame Nkrumah was the leader of the liberation movement in Ghana, formerly a British colony known as the Gold Coast. He was also its first leader as an independent state.

The book is made up of pieces: a shorter book, letters, an essay, a lecture. CLR James, a Marxist from the Caribbean who wrote The Black Jacobins in the 1930s, gives first an account of the revolution, then a hint of some of the problems encountered by the newly-independent state, and finally a developed meditation on problems of underdevelopment in former colonial nations.

The second of those three elements is the weakest. The brief parts of the book which hint at problems and criticisms of the independent Ghanaian state seem hand-wringing and uncertain.

The other two elements are strong, though all indications are that James’ politics have changed a great deal between the 1930s and the 1960s. The key criterion, class, is not absent but it is not in the first place. I know that in the 1930s James, Nkrumah, Kenyatta and George Padmore all moved in the same circles in London.

All in all, the book opened my eyes on the specifics of the Ghana Revolution, which I’d known nothing about, and on the problems of underdevelopment.

I can’t comment in detail due to my lack of knowledge, but here are a few quotes that jumped off the page at me.

On the poet Césaire:

‘Césaire’s whole emphasis is upon the fact that the African way of life is not an anachronism, a primitive survival of history, even of prehistoric ages, which needs to be nursed by unlimited quantities of aid into the means and ways of the supersonic plane, television, the Beatles and accommodation to the nuclear peril. Césaire means exactly the opposite. It is the way of life which the African has not lost which will restore to a new humanity what has been lost by modern life with ‘its rebellious joints cracking under/ the pitiless stars/ its blue steel rigidities, cutting through the/ mysteries of the flesh.’ (23)

On European commentators:

‘they see themselves always as the givers, and Africans as the takers, themselves as teachers and Africans as the taught. In the thousands of reports, articles, speeches, that I have read about events in Ghana, I have never seen a single word, the slightest hint that anything which took place there could instruct or inspire the peoples of the advanced capitalist countries in their own management of their own affairs, and this is as true of the friends of Ghana as of its enemies.’ (38)

‘The reader will not understand these events or what is taking place all over Africa today unless he makes a complete reversal of traditional conceptions as to where is law and where is lawlessness. The disciplined community obeying its own laws was the masses of the people in Accra. The mob was the heterogeneous collection of chiefs, government officials, merchants and lawyers.’ (46)

On the people of Ghana:

‘[They were] governed by a long tradition of democracy in which the chief was no more than a representative of his people who could be, and often was, ruthlessly removed if his actions did not accord with their wishes. This was the condition of some seventy-five percent of the population.’ (53)

On women in Ghana:

‘The traders for generations have been the women (Nkrumah’s mother was a petty trader)… Thus in Accra there are thousands of women in action in the market, meeting tens of thousands of their fellow citizens every day. European visitors and officials up to 1947 saw in these markets a primitive and quaint survival in the modern towns. In reality here was, ready formed, a social organisation of immense power, radiating from the centre into every corner and room of the town.’ (55)

On protestors:

‘They used the Lord’s Prayer:

O imperialism which are in Gold Coast

Disgrace is thy name…

‘The Apostles’ Creed:

I believe in the Convention People’s Party,

The opportune saviour of Ghana,

And in Kwame Nkrumah its founder and leader…

‘The Beatitudes:

Blessed are they who are imprisoned for self-government’s sake, for theirs is the freedom of this land.’ (108)

On Europeans who acknowledged Nkrumah’s power as an orator:

‘[They] added the sneering qualification “among Africans”. What mass oratory could Nkrumah practise among the Europeans? Or was he to go to China?’ (113)

Four quotes from Nkrumah himself:

- ‘We prefer self-government with danger to servitude in tranquillity.’

- ‘There come in all political struggles rare moments hard to distinguish but fatal to let slip, when even caution is dangerous. Then all must be on a hazard, and out of the simple man is ordained strength.’

- ‘We have the right to govern and even to misgovern ourselves.’ (117)

- ‘What other countries have taken three hundred years or more to achieve, a once dependent territory must try to accomplish in a generation if it is to survive. Unless it is, as it were, ‘jet-propelled’, it will lag behind and thus risk everything for which it has fought.’ ( 157)

Misc:

‘That this revolution was blood and bone of the twentieth century is shown not only by its planned character, but also by the role of the Trades Union Congress. Ten thousand workers organised in a union are ten times more effective than a hundred thousand individual citizens.’

Here is a longer quote, photographed rather than transcribed because of its length: