It is May 1920, and the Bolshevik sailor Raskolnikov is on the deck of the destroyer Karl Liebkencht, watching as 1,500 Red sailors land on the coast of Iran. Black plumes of shellfire erupt on the shore as the guns of the Red fleet bombard the British Empire’s elite Ghurka soldiers.

It is 1921, and the ‘mad Baron’ Ungern-Sternberg, having seized Mongolia’s capital and received the blessing of its priest-king, is setting out for war against the Soviet regime.

It is 1922, and the last White Guard regime still clings to power in Vladivostok in the Far East. General Horvath has given up all pretenses and pretensions at democracy, and rules over an openly monarchist regime, backed by the Japanese military.

It is 1923, and the last White Army, now abandoned by the Japanese, still clings to existence in remote and barely-habitable reaches of the Pacific coast.

It is 1926, and the Red Army is once again fighting the Basmachi in Central Asia.

The conclusions of the Russian Civil War were even messier and more manifold than its beginnings. As with the question of when it started, it’s helpful to think of two civil wars – a broad period of violence in the Tsarist Empire and its successor states lasting from 1916 to 1926 or from 1917 to 1923, and a narrow and more defined struggle between the Red Army and the White movement initiated by Generals Kornilov and Alexeev.

Revolution Under Siege never set out to be a comprehensive history of the ‘broad’ Russian Civil War, but I’m glad I paused the main story to write four or five posts about Central Asia and the Basmachi. This was a way of paying indirect homage to all the theatres of war which my main narrative has been obliged to neglect, such as North Russia, the partisan war in Siberia, the Caucasus and the Baltic States. To this we must now add the Russian Far East and Mongolia, which were very significant after 1920.

Rather than write another three or four seasons of Revolution Under Siege dealing with a period when the Revolution was, in fact, no longer under siege, I’m going to sum up as much of it as I can in one post. These are all things I’d write whole episodes about, if I had infinite time and if the scope of this project were just a few degrees wider.

North Russia

In the Arctic Circle Red forces battled with British and American troops directly from 1918 through to 1920. This was a small and slow war fought in extremely harsh conditions. Each side proved capable of landing heavy blows on the other, but by 1920 the Reds had the upper hand on the frozen battlefields and the tide of political opinion in the Allied nations was turning decisively against the Russian adventure. The Allies pulled out at last, and the Reds retook Murmansk and Archangel’sk in early 1920.

Siberia & the Far East

The Reds led an uprising in Vladivostok in January 1920 – a time when the ground was splitting under the feet of Kolchak’s regime. But this uprising was put down by the Cossacks of Semyonov, assisted by the Japanese military. Its leaders, including the noble-born Bolshevik Sergey Lazo, disappeared to an unknown fate.

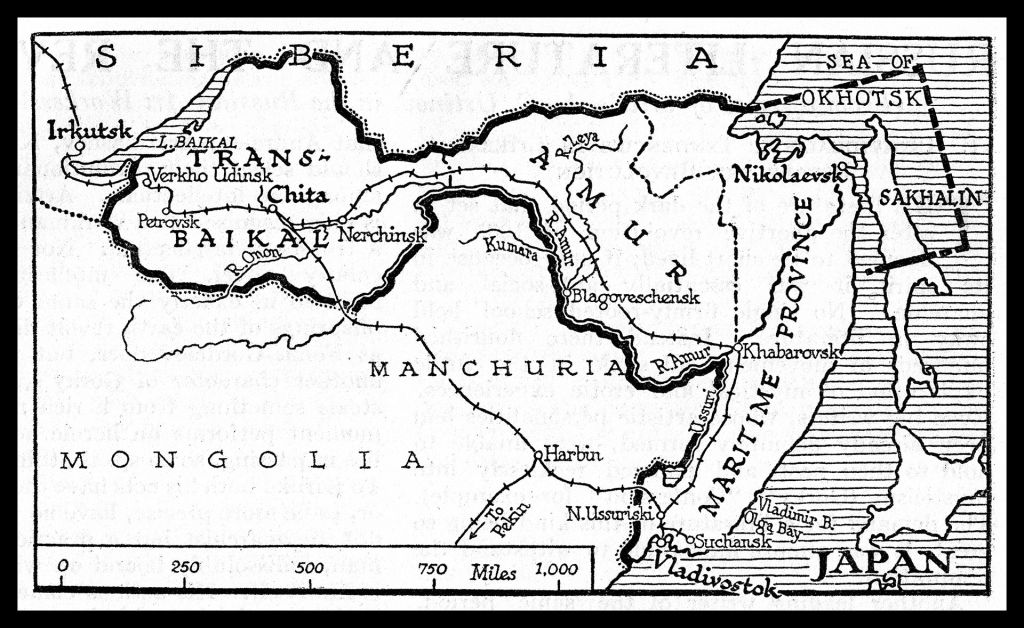

A few months later the Reds took Irkutsk and set up the Far Eastern Republic in coalition with Mensheviks and SRs. The Far Eastern Republic had its own Red Army and its own emblem. For the next few years it made slow and steady advances against Semyonov’s Trans-Baikal fiefdom and finally, after the Japanese withdrawal, took Vladivostok from General Horvath in 1922. The last major city in the hands of the Whites was now in Red hands.

Mongolia

The Russian Civil War spilled over organically into Mongolia: White Russians fled there, some to settle peacefully, others to raid over the border.

When Baron Ungern moved his forces from the Trans-Baikal into Mongolia, terror seized the Chinese forces occupying the country. According to the White soldier Dmitri Alioshin, the Chinese set about slaughtering every White Russian they could find. The White Russians, who despised the Chinese with intense racism, responded in kind. The White Russians were mostly skeptical of the unhinged Baron and would have avoided him in the normal course of events, but they were driven into his arms by the actions of the Chinese military.

Ungern and his forces endured the steppe winter of 1920-21, and in February they marched on the Mongolian capital city (known variously as Urga, Ikh Khuree, Ulan Baatar). They seized it from superior numbers of Chinese soldiers and began several days of intense slaughter and looting.

Meanwhile the Reds had made an alliance with Sukhbaatar and Chaibalsan, two more left-wing Mongolian leaders who opposed Ungern. A joint Soviet and Red Mongolian army crossed the border. Ungern hastened to meet it. His luck ran out. After defeats, he fled with small numbers, who turned against him and abandoned him in the wild. A Soviet Mongolia was established, and Ungern was captured, tried and executed in Russia.

The Caucasus and Persia

Victory in South Russia spilled over into a string of major gains in the Caucasus. In Azerbaijan the local communists overthrew the Musavatists, the nationalist forces supported first by Turkey and then by Britain. Neighbouring Armenia also contained many pro-Soviet elements and like Azerbaijan it was soon its own Soviet Republic. So secure were the Caucasus that Baku, which had been in enemy hands mere months before, was chosen as the venue for the September 1920 Congress of the Peoples of the East.

Meanwhile the Whites had withdrawn their Caspian Fleet, consisting of 17 ships along with 50 guns, to the British-occupied port of Enzeli in Persia (Iran). Raskolnikov led a Red striking force on a surprise raid, took and held the town for days, and returned the ships, munitions and materiel to Soviet Azerbaijan and Soviet Russia. In Persia itself, the Russian Revolution produced its shockwaves in the form of popular guerrilla leaders. The Enzeli raid, meanwhile, embarrassed the British so badly the Persian parliament rejected a proposed treaty that would have utterly subordinated the country to London.

The Daghestanis had troubled Denikin’s rear at a key moment. In 1920 some Daghestanis revolted against the Soviet power, though as many remained neutral and as many again were pro-Soviet. The Red Army suffered around 5,000 fatalities in tough battles over mountains, defiles and villages perched over sheer cliffs.

Georgia did not come into the Soviet orbit until 1923. The manner in which this was achieved was extremely controversial. It was the subject of Lenin’s final political struggle before his death. Though in extremely poor health, he waged a campaign against Stalin and his ally Ordzhonikidze. The latter pair were guilty of the premature entry of the Red Army into a Georgia that was not quite ready to accept it, and for the heavy-handed manner in which they dealt with the Georgian communists.

Makhno

Makhno and his Anarchist Black Army had been making open warfare against the Soviet power. But during the campaign against Wrangel the Anarchists agreed to a truce, sent some forces to help deal with Wrangel and, more importantly, stopped raiding in the rear of the Red Army.

Even taking into account how deep the hostility was between the Red Army and the Black, and how shallow their cooperation was, there’s something shocking about the Michael Corleone-like speed and ruthlessness with which the Anarchists were dealt as soon as Wrangel was out of the way. The commander of the Anarchist detachment which had fought in Crimea was summoned to Red Army HQ, but it appears it was a trap. He didn’t make it out alive.

After this, Makhno’s fortunes spiraled. He ended up with a couple of dozen companions fleeing across the Romanian border with the Red Cavalry hot on his heels. A humble life as an exile in Paris awaited him.

Internal Revolts

We have traced the fronts of the Civil War clockwise from Murmansk to the Black Sea. Now we return to the heart of European Russia. In late 1920 and into 1921, Tambov Province saw a rural revolt against Soviet power which far exceeded any peasant unrest during the Civil War. Soviet officials and their families were slaughtered out by furious insurgents, who organized into an army along regular lines.

Early 1921 saw a general strike of workers in Petrograd demanding better rations and fewer restrictions on political rights and economic activity. After the end of the strike, in March, the Kronstadt sailors revolted with a mix of similar demands and more far-reaching demands. Suppressing the Tambov and Kronstadt Revolts required serious military operations.

Smele says ‘it has been estimated that’ 2000 sailors were executed after the suppression of the revolt. If so, the scale of the reprisal was truly shocking. On the other hand Marcus Hesse, drawing on Paul Avrich, paints a different picture:

Of those who didn’t flee, several hundred were sentenced to death, although most were then amnestied. Others were imprisoned in camps intended for prisoners of war — some later ended up in the Solovetsky prison, which opened in June 1923 and later became part of the notorious ‘GULAG’. Several years later they were released under a general amnesty.

Leftists have been arguing about Kronstadt for a hundred years, and rather than wade in here I will just make one observation. Each year of the Civil War began, for the Soviets, with a promise of peace that was soon dashed. Spring would invariably bring with it new White and interventionist offensives. The familiar cycles of revolt and foreign intervention would repeat themselves with what must have become a dreadful and crushing sense of inevitability. The Kronstadt Revolt took place only a few months after the defeat of Wrangel, and precisely on the cusp of the Spring campaigning season. Sure, the Kronstadt sailors were raising democratic demands; the Don Cossacks and Right SRs, too, had raised democratic demands but had ended up spilling their blood for the White militarists. With the benefit of hindsight we know that the war, in European Russia at least, was over. The Communists did not have that benefit. We can hardly understand Kronstadt without an appreciation of the fear they had, a fear based on lessons learned in blood, of another year of war.

These revolts would not have taken place during the struggle against the White Armies, because neither the Tambov peasants nor the Kronstadters wanted to see a return of the landlords. But once Wrangel was defeated, the floodgates were opened for many serious grievances to find expression in armed revolt. The horrific conditions endured by both civilians and military during the Civil War meant there was widespread anger. Much of this was directed at the Soviet power and the Communist Party, as they were the regulators and arbiters in this austere armed camp. From both the factories and the naval base of Kronstadt, the leading elements from 1917 were absent: dead like Markin at Kazan, commanding fleets like Raskolnikov, or serving in the state apparatus.

The Kronstadt Revolt in particular, which took place during the Party Congress, served as a warning to the Soviet government that the Spartan wartime regime had been maintained for far too long, and must be dismantled as a matter of urgency.

So, when did the Civil War end? One answer would be 1922, with the conquest of Vladivostok from the Whites. Another would be 1926, with the defeat of the Basmachi. Antony Beevor ends with sailors being shot after the Kronstadt Revolt – a suitably depressing scene for his narrative purposes. But in these three cases we are losing sight of the big picture.

So I’m going to say November 1920.

The former Russian Empire was at war between Spring 1918 (the revolt of the Czechoslovak Legion and the Cossacks) and Autumn 1920 (the treaty with Poland and the defeat of Wrangel). This was an all-out war with profound geopolitical importance, fought between irreconcilable and defined adversaries, with clear criteria for the victory or defeat of each side.

This war was the most important of a complex of armed struggles which engulfed the collapsing Russian Empire in what we could call a ‘Time of Troubles’ lasting from 1916 to 1926 in Central Asia and from 1917 to 1923 in Russia itself. It is the narrow Civil War rather than the broad ‘Time of Troubles’ which has been the focus of Revolution Under Siege. But the two are of course not neatly separable.

Further Reading

On Enzeli and Persia: https://www.marxists.org/history/ussr/government/red-army/1918/raskolnikov/ilyin/ch05.htm

On Daghestan, see Eduard Dune

On Georgia, see Lenin’s Final Fight, Pathfinder Press, 1995, 2010

On Kronstadt: See Smele, p 200-210, also https://internationalsocialist.net/en/2021/04/revolutionary-history