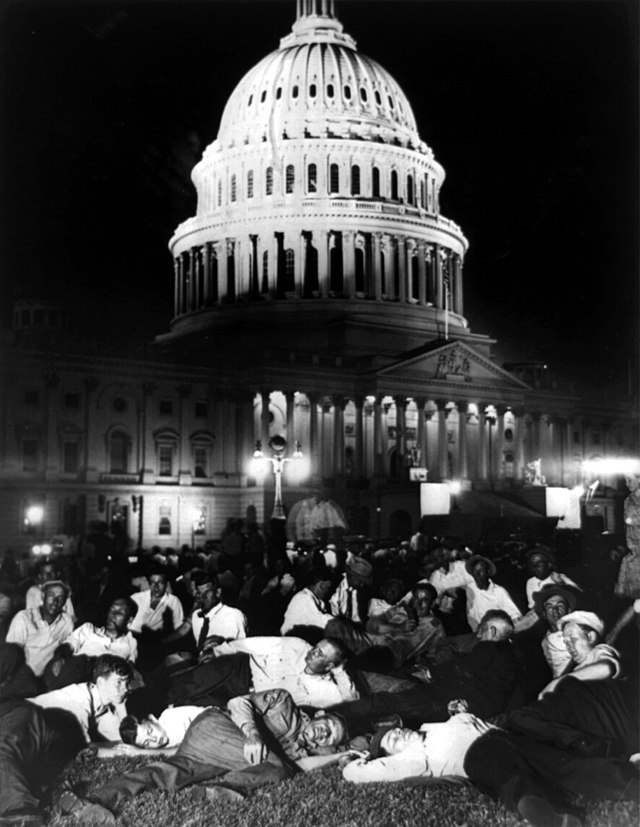

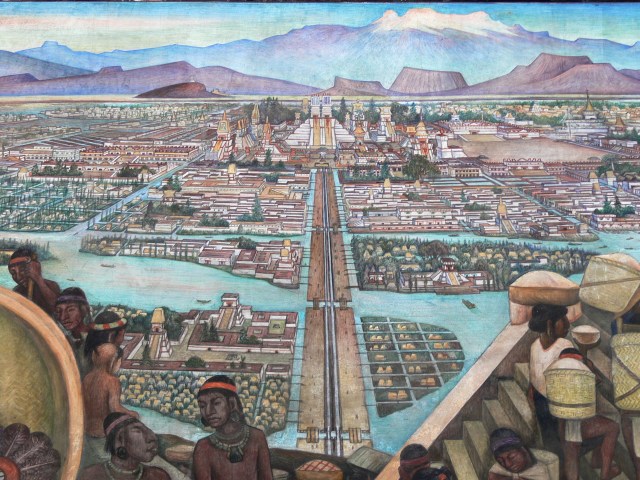

The Lacuna is a 2009 novel by Barbara Kingsolver about a young Mexican-American man, Harrison Shepherd, growing up in the early 20th Century. During his fictional life, spent back and forth between Mexico and the USA, he encounters real events and people, such as when he sees the Bonus Marchers beaten and gassed off the streets of Washington DC in 1932, makes friends with Diego Rivera and Frieda Kahlo in Mexico City, and back in the US finds himself in the firing line of the McCarthy Red Scare.

It’s a great novel that deserves all the praise and prizes that it got. In this brief post I want to zoom in on one interesting feature: its depiction of the Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky. Trotsky, who lived in exile in Mexico city from 1937 until his murder in 1940, occupies a prominent place in the story. His depiction is something I’m going to praise but also criticize.

Kingsolver, who cut her teeth writing about miners’ strikes, treats the workers’ leader Trotsky with great sympathy. He appears to Harrison as a short, strong man with the dignified appearance of an older peasant, who is passionate about animals, nature and literature as well as politics. He employs Harrison as a secretary and, when he stumbles upon the young man moonlighting as a writer, gives him precious encouragement. An exile from Stalin’s Soviet Union, Trotsky is more melancholy than angry. Harrison is a witness to Trotsky’s murder and is haunted by the experience.

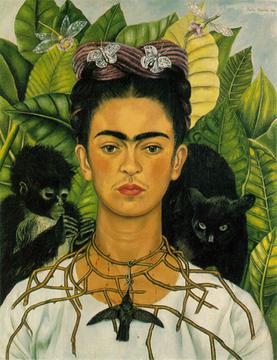

As an example of how she depicts Trotsky, in his affair with Frieda Kahlo (they did the dirt on their respective partners, Natalia Sedova and Diego Rivera), Kahlo comes out looking a lot worse than him. Harrison is Kahlo’s friend and confidante, and he judges her more harshly, probably because he knows her better; Trotsky is up on a pedestal and largely escapes judgement.

Kingsolver is interested in Trotsky but far more interested in Kahlo. We see Kahlo’s sharp edges, we are invited to judge her at times. But I guess this is because the author decided to make her a central character, to spend more time and energy on her. Trotsky gets comparatively less attention from the author, so we get a simpler picture of him. This is all fair enough. But this leads the novel into some avoidable missteps.

Funerals

It’s not impossible that Trotsky would have employed Harrison as a secretary. Harrison is a veteran of the Bonus March, a supporter of ‘the dictatorship of the proletariat,’ (understood by him to mean democratic workers’ power) and a member of the leftist artsy milieu in Mexico City. Harrison is also young, and Trotsky was more politically tolerant toward younger comrades. But Harrison is, for all this, not very knowledgeable about or active in politics. I think Trotsky would have sooner entrusted such a key role to members of his own organisation, the Fourth International.

So it’s a very strange moment when Harrison asks how Stalin and not Trotsky ended up in charge of the Soviet Union. This should be something which Harrison already knows about and has developed opinions about, if he’s living and working in a trusted position in Trotsky’s household.

It’s a problematic moment in a bigger way, too. The real Trotsky wrote entire books about Stalin’s rise to power, so we know what he would have said. The explanation he gives in The Lacuna is wide of the mark. Trotsky, earnest and visibly pained by the memory, tells Harrison that he missed Lenin’s funeral because of a devious prank by Stalin. And so Stalin took centre stage at the funeral, and so, in this version of events, he became the sole possible successor to Lenin. I remember being told this by my school history teacher as an aside, as a touch of pop-history anecdote material, but I haven’t come across it anywhere since. Maybe it’s true as far as it goes, but it doesn’t answer the question.

And it’s definitely not the first answer Trotsky would give. In real life, Harrison would want to put the kettle on and pull up a comfortable chair before he asks Trotsky how Stalin ended up in power. Trotsky would not have spoken of personal intrigues; he was far more partial to grand socio-economic analysis and theoretical debates. If you open up his key book on the subject, The Revolution Betrayed, you can see this in the title of the first chapter; it’s not ‘Stalin: Devious Bastard’ but ‘The Principle Indices of Industrial Growth’.

Yeoman farmers

In another strange scene, Trotsky laments the latest news from Russia: now Stalin is going after the ‘Yeoman farmers.’ But Stalin had started in on the ‘Yeoman farmers’ (kulaks) in earnest from 1929, and this conversation is happening around ten years later! In the early 1930s forced collectivisation and the ‘liquidation of the kulaks’ led to famine and terror on a huge scale. It was one of the most traumatic episodes in Soviet history and Trotsky wrote about it at the time. It wouldn’t have been news to him by the time he was in Mexico. In any case by then there were no kulaks left.

Trotsky in The Lacuna seems to regard these ‘Yeoman farmers’ as a key constituency whom nobody should mess with. This wasn’t the case. While Trotsky condemned Stalin’s onslaught on the peasantry and national minorities, he would still have used the derogatory term ‘kulaks’ rather than ‘Yeoman farmers.’ He saw the kulaks as a problem (though he advocated gradual and peaceful solutions) and earlier (in the mid-1920s) he condemned his opponents, including Stalin, for enacting policies that enriched and empowered this social layer.

‘pedantic and exacting’

In 1938 Trotsky’s son and close comrade Leon Sedov died in Paris, likely poisoned by Soviet agents during a routine surgery. In a powerful obituary, Trotsky expressed regret over his own often difficult personality:

I also displayed toward him the pedantic and exacting attitude which I had acquired in practical questions. Because of these traits, which are perhaps useful and even indispensable for work on a large scale but quite insufferable in personal relationships people closest to me often had a very hard time.

A more rounded novelistic portrayal of Trotsky would show us this ‘pedantic and exacting’ side, which was not a figment of Trotsky’s imagination – and perhaps his own occasional pang of regret over it. As his secretary, transcribing his extensive writings, Harrison would not only experience on occasion this ‘very hard time’ but would read practically every word Trotsky wrote. Someone as raw and open as Harrison would (rightly or wrongly is of no concern here) see some of Trotsky’s writings as ultra-principled or hair-splitting. This would especially be the case in the late 1930s; the extermination of all his allies and supporters back in the Soviet Union left Trotsky isolated, debating with the few survivors over questions which had no easy answers.

This depiction of Trotsky is incomparably more accurate and fair than the gothic, depraved supervillain we see in the 2017 Russian TV series. The 1972 movie The Assassination of Trotsky, starring Richard Burton in the title role, is a fair depiction and, I think, a good movie. We do see some steel in Trotsky’s character along with vulnerability. But I should mention that while I am far from its only defender, it was heavily and widely criticized as a film.

It’s believable and accurate that Harrison would encounter Trotsky and see a kind, curious, haunted man. But since he lived with him for a few years, he would see that like many great leaders and writers, Trotsky had his more negative personal traits. A more nuanced Trotsky, like the multi-faceted Kahlo we come to know in The Lacuna, would be all the more sympathetic for our having seen various sides of him.