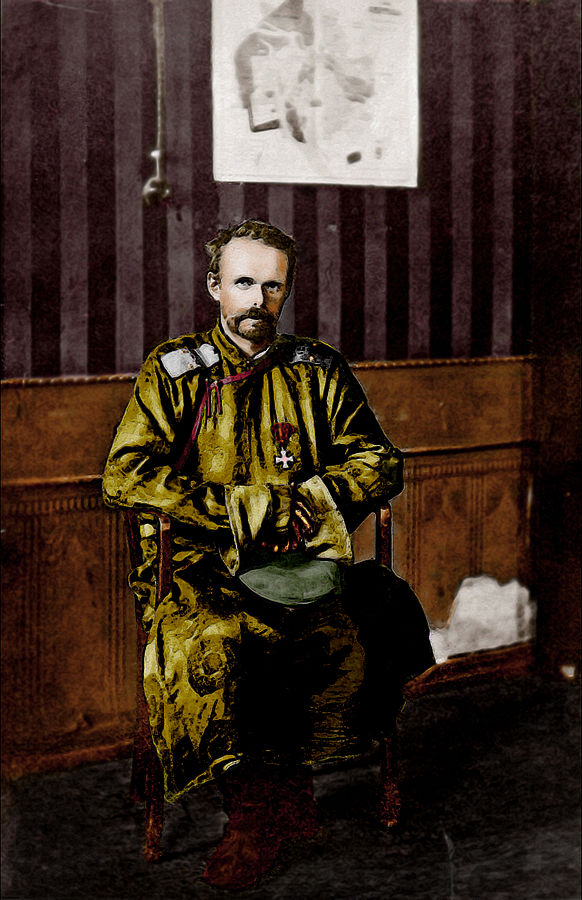

Baron Roman Ungern von Sternberg was a cavalry officer who hacked a bloody path through revolutionary Russia, drove a Chinese occupation out of Mongolia, and aimed to become a new Genghis Khan.

This biography by James Palmer gives an engaging and hair-raising account of Ungern’s life. A child of the Baltic German nobility, raised in an atmosphere of contempt for the Estonian peasantry whose labour sustained his family, he was expelled from every educational institution he set foot in, generally for violence. He only settled down to a steady life when the battlefield gave his brutality an outlet during the 1905-6 Russo-Japanese War. He joined the ranks and received rapid promotion to the officer corps in a Cossack unit. Later during World War One he displayed near-suicidal bravery, and off the battlefields he was prone to duelling and to administering drunken beatings to servants.

Revolution & Civil War

As the war ground on, claiming millions of Russian lives, Ungern became part of a military scheme to recruit a unit of Buriats, a Mongolian people living within Russia. So when the Revolution and Civil War came they found Ungern on the Mongolian border commanding a large force of Buriats.

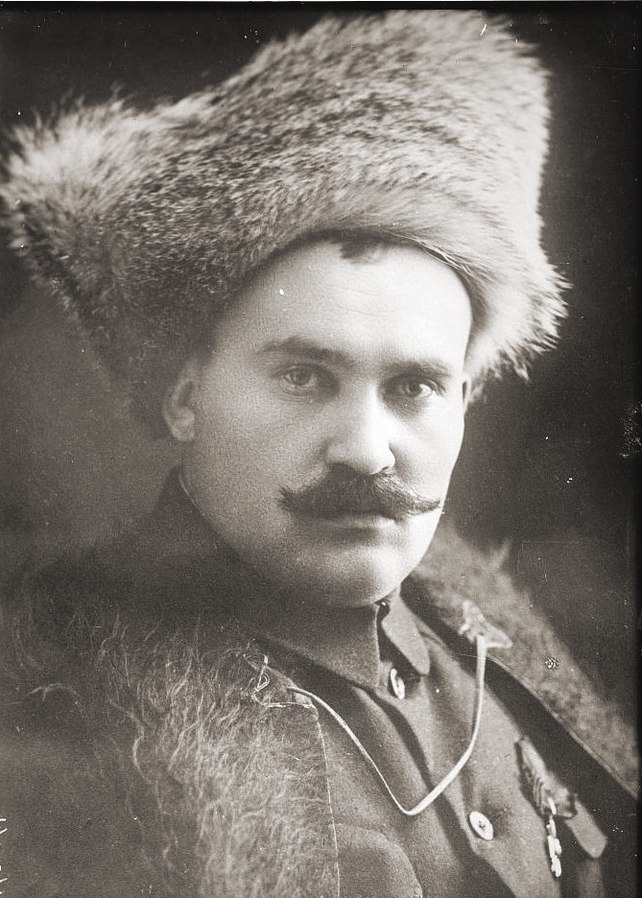

Ungern was a close collaborator of a Cossack officer named Semyonov. With the outbreak of Civil War, Semyonov became a key figure in the White Armies. He was a bandit on a large scale, a warlord whose cavalry forces dominated an area larger than many European nations, both an asset and an embarrassment to the Whites. Ungern was his right-hand man.

In 1920 when Admiral Kolchak’s White armies collapsed and the Red Army advanced across Siberia, Ungern and his thousands of fighters crossed the border into Mongolia.

After a harsh winter in the wilderness Ungern marched on the then-capital, Urga/ Ikh Khuree, and drove out the Chinese occupiers in early 1921. The height of his power followed: the Mongolian Buddhist church officially recognised him as the god of war and as the reincarnation of an eminent religious leader from the early 19th century. However, inside of a few months Ungern was being challenged by socialist Mongolians led by Sukhbaatar and Chaibalsan, who, with major Soviet supplies and aid, seized the border town of Kiatkha. Ungern marched north to fight them, and met with a terrible defeat. Then, as Soviet forces advanced into Mongolia, Ungern led a straggling army through desolate swamps and hills until his own soldiers, horrified by his wild plan to invade Tibet, mutinied and turned him over to the Reds.

If you want to read more about the Russian Civil War, keep an eye out for my upcoming series, Battle for Red October. Subscribe for free to receive an update by email for my weekly post.

Violence

Throughout his career as a White leader, Ungern killed every communist he encountered, and their children too, so that nobody would be left to seek revenge. He also believed that he could sense, by staring intensely at a prisoner, whether they were secretly ‘a Jew or a commissar’, and if he divined that they were he would kill them too. Palmer details Ungern’s sadistic and disgusting methods of execution and torture, and the horrific scale on which he employed them.

During the heyday of the White Armies Ugern ruled the border town of Dauria, which became ‘The gallows of Siberia’, where the hills outside town became stained red with the blood of prisoners. These victims were sent to Ungern by other White leaders such as Kolchak who liked to pretend they didn’t know what he was doing.

Ungern had strange views about military discipline. Almost everyone close to him seems to have been on the receiving end of horrific beatings. A hundred blows to each part of the body was a standard punishment. Forcing a victim to shiver naked on a frozen lake was another. Execution and torture were normal.

Palmer has travelled extensively in the lands which Ungern trod, and he conveys a real sense of the setting. He is an engaging narrator, capable of capturing the imagination, very self-assured, with footnotes that delve into his own interesting anecdotes and meditations. His description of Ungern’s seizing of Ikh Khuree is very vivid and will stick in my mind for a long time. He does a great job of conveying Ungern’s character, and of explaining the complex political-religious influences that operated on him. The book is very clearly aimed at British readers; while I’m not sure he always shows sufficient respect to the Mongolian people in his remarks about them, I’ll extend him the benefit of the doubt.

In general, Palmer doesn’t pull his punches on Ungern, but towards the end of the book he seems to go a little soft on him, claiming that ‘the Soviets… made him look like an amateur’ when it came to killing. Of course, he’s talking about events over a decade later after Stalin had seized power; there was no figure remotely comparable to Ungern on the Red side during the Civil War, and on his own smaller scale he gave Yezhov and Beria a run for their money. Palmer himself notes that the early Soviet regime in Mongolia was not marked by terror or coercion. They even kept in power the corrupt, murderous and utterly selfish priest-king of Mongolia, the Bogd Khan. It’s frustrating how an author can fail to notice the profound contrast between the early years of the Soviet Union and the later Stalinist regime of terror. Instead, as is the common practise of British writers, he telescopes it all together – the idea being that Stalin and the political tradition he exterminated were fundamentally the same. Far from looking like an amateur, Ungern’s violence gives us an insight into the form of proto-fascism that would have enjoyed a bloody reign over a disintegrating Russia if the Whites had been victorious.

The final paragraphs of the book left me with a bad taste in my mouth, as Palmer decided it would be a good idea to end this long horror story by telling us about a Mongolian woman he met who praised Ungern. ‘It would have pleased him,’ Palmer concludes with complacent magnanimity.

Beliefs

While Ungern seems at first like a disturbing freak of nature, the truth emerges that he was in every respect part of broader trends, and that every facet of his weird amalgam of beliefs was connected to his lived experience and the institutions that shaped him.

To begin with, Ungern was a Baltic German aristocrat, conditioned from his earliest days toviolent, elitist and racist. To him it was obvious that ‘Slavs’ couldn’t rule themselves, and must be ruled by the firm hand of the Romanovs, or as a second preference by German nobles, if they didn’t want to be ‘led astray’ by ‘the Jews.’ But Ungern’s racism was awkward and unusual: he inverted the ‘Yellow Peril’, believing that Europeans were degenerate while ‘the peoples of the East’ were strong and warlike. His violence fell foremost on Jewish people, next on Europeans and Chinese, and least of all on Mongolians.

This bleeds over into his anti-revolutionary paranoia. He believed that the Communist Party was founded 3,000 years ago in Babylon and that it was a cosmic, satanic evil. The standard form of anti-communist bile in the 1920s was to explain that communism and revolution sprang from the ‘barbarity’ of ‘Asiatic’ Russia, but for Ungern Marxism was a product of modernity, of the degenerate ‘West’ engulfed in a ‘revolutionary storm.’ Other White leaders, who touted a constitutional monarchy or even a republic, disgusted him. For Ungern, only a new Genghis Khan could save the world. It appears that he couldn’t really tell the fundamental difference between, say, Lenin and Sun Yat-Sen: they were all evil ‘revolutionaries’ in his eyes.

Both Ungern and his collaborator Semyonov were mass-murdering sadists. But Semyonov was extraordinarily corrupt and luxurious, with a weakness for orgies and drink, while Ungern was intense and ascetic.

Ungern was a bore on the subject of how Mongolian medicine could supposedly cure diseases which ‘western’ science could not, and his religious beliefs mixed Buddhism with Lutheranism and Orthodox Christianity. The esoteric mysticism associated with Madame Blavatsky and the Theosophists also informed his religious convictions. It appears that he absorbed a whole lot of ‘occult’ and ‘magical’ readings before the war. The same basically confused, shallow ‘spiritual’ eclecticism was of course a feature of Nazi ideology, particularly in the case of Himmler.

Lastly, Ungern’s sadism and obsession with war were part of the wider tradition at the time of seeing war as something noble and ‘virile’, the antidote to a vaguely-defined ‘degeneracy’; and these attitudes were obviously further fed and fattened every day of his life by the brutality of Tsarist military discipline and by the trauma of the battlefield.

As opposed to a historical curiosity or mystery, the more I read about Ungern, the more I saw him fitting right into his historical context. His racialism and mysticism, far from being just eccentricities, were 100% of his time. His violence was the violence of counter-revolution. His orientalism was not ‘ancient wisdom’ – it was a very modern delusion, and he was an essentially modern figure, in so many ways emblematic of 20th century fascist and reactionary thought. He was on the edge of the White cause both politically and geographically – but the old regime and the White cause created him, and behind the ‘democratic’ facade carefully projected for the benefit of the Allies, beasts like Ungern lurked.