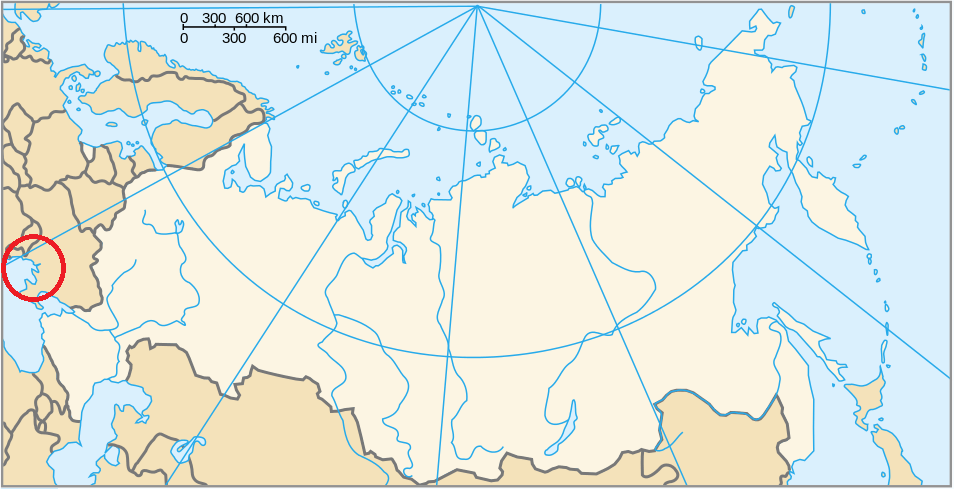

This post tells the story of how the French military invaded Ukraine and was defeated – by its own personnel. The French soldiers and sailors fraternised and mutinied under the Red Flag, singing the ‘Internationale’ – symbols of the regime they had been sent to fight.

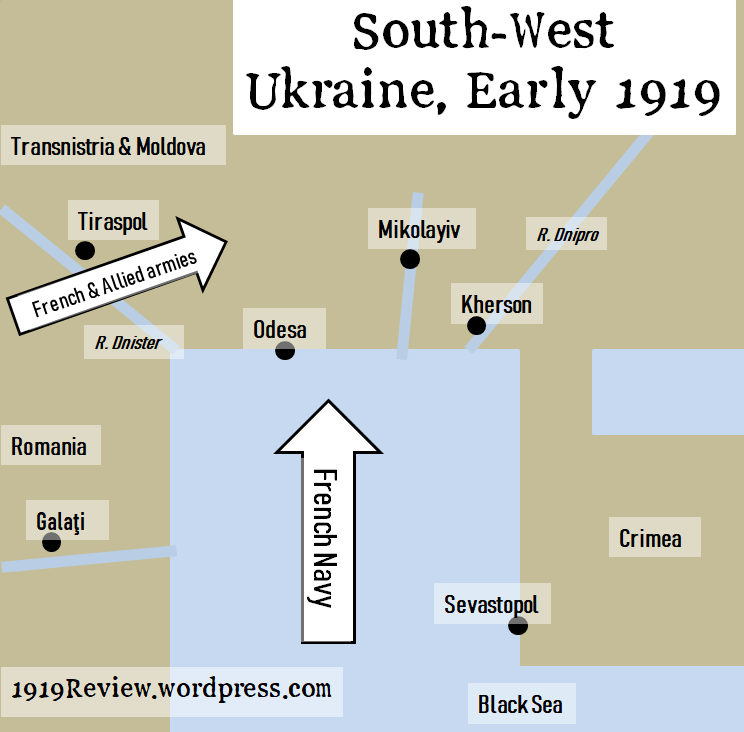

Tiraspol

Let’s imagine a member of the 58th Infantry Regiment, from Avignon in the South of France. This soldier would have spent a large part of the First World War fighting in Bessarabia (today called Moldova). But when the war ended in November 1918, instead of being sent home or given quiet garrison duties, the French soldier of the 58th received orders to cross the Dnister River and to enter the former Tsarist Empire – in other words, to stick his hand into the furnace of the Russian Civil War.

Some soldiers in the 58th had been involved in the vast mutinies which swept the trenches of the Western Front in 1917; they had been deported to this part of the world as a punishment. The average soldier in the Regiment might also have known that there was a revolutionary committee active in the ranks – there was Corporal Thomas, and the soldier Tondut who had been in the Socialist Youth.

The 58th were ordered to capture Tiraspol from the Reds (Tiraspol is today the capital of the breakaway republic of Transnistria). A French scouting party was captured by the local Tiraspol Red Guards, but treated well. The Red Guards had lengthy political discussions with them, then released them with their weapons. So when these scouts came back to the French ranks, they were practically enemy agents.

When the whole regiment was ordered to advance on Tiraspol, there were protests: ‘So, that’s what it is! We’ve come to invade Russia! It’s the war again! We’ve had enough! Enough!’

To most people at the time, Transnistria and Ukraine were simply parts of ‘Russia.’

An officer replied to the complaints of the soldiers: ‘The Russians borrowed money from us, which they refuse to pay us. We shall encounter revolutionary patrols, but since they are badly commanded and lack arms, the Bolsheviks will flee.’

But when the regiment advanced, it came under machine-gun fire. By prior agreement, the French rank-and-file refused to fire back or to advance.

Refugees streamed out of the town, and French artillery fire swept the fleeing carts with shrapnel. The artillerymen could not see the civilians being killed, but the infantry, already mutinous, saw the death and destruction, and grew even angrier. They cut the telephone wires so that no orders could reach the artillery. Then they deserted. They packed up and returned across the river to the town of Bender.

The 58th Regiment only entered Tiraspol after the Polish army had captured the town from the Reds. The mutinous French soldiers were soon disarmed, shipped to Morocco, and drafted into disciplinary companies.

But the Tiraspol Mutiny was just the beginning.

Kherson and Mikolayiv

Between late 1918 and early 1919, in a complicated series of acts, south-west Ukraine passed from German to Allied occupation. There were 10,000 French, 30,000 Greeks, 3,000 Poles, 32,000 Romanians and apparently 15,000 of Denikin’s White Guards in the vicinity of Odesa.

In November 1918 General Franchet D’Esprey anticipated the mutinies: ‘The moment military operations are shifted to Russian territory, there will be a danger that active revolutionary propaganda may be attempted among the troops.’

He supported a ‘carrot and stick’ approach. He urged officers to see that troops were provided with good food and billets. Meanwhile they must ‘ruthlessly’ deal with every violation of discipline.

After the hell of the First World War, the French soldier now feared that his government had dreamt up a whole new war for him to die in. And the political justification for this war was even more flimsy than for the last one.

The underground Communist movement gave expression to this mood – local Ukrainian communists published leaflets and even a newspaper in French, and distributed them among the occupying forces. Here is a part of an article from that paper:

Today we have a right to ask why it was that when Russia was headed by a tsar, by an autocratic despot, our government was on friendly terms with her. Now everything has changed. Russia is now undeniably a Republic, a Soviet republic. Are not our two sister republics akin in their ideas and tendencies? Could they not unite and work for a common cause? Is it perhaps because the Soviet republic is too socialistic?

The French at the time ruled a vast colonial empire, and it appears a majority of their 10,000 soldiers were in fact from Algeria and Senegal. Later, war veterans would play an important role in the liberation struggles on the African continent. But in 1919 the high command considered them reliable, even as their trusted enforcers.

All the same, in November French ‘colonial’ troops at Archangel in the Arctic Circle had staged a mutiny. And at a key moment in early April the 1st Zouave Route Regiment (an Algerian unit) refused to harness horses to artillery, in effect aiding the Red advance.

Among English-speaking historians there is a tendency to downplay Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War. The attitude is: ‘Quit complaining: we barely invaded you at all.’ We are told that there was very little direct fighting between Allied and Red forces… apart from the fierce battles in North Russia; and with the Japanese in the Far East; and the unauthorised frontline role of British personnel in the South. Likewise at Mikolayiv and Kherson there was heavy fighting. But we should grant the Anglophone historians this much: the Allied rank-and-file were not keen to fight. In early March when the fighting was heaviest, some refused to go to Kherson, and others, when they arrived, refused to fight. In the end Ataman Grigoriev (whom you will recall from ‘Warlords of Ukraine: Continued’) drove 1,000 French and Greek soldiers out of Kherson.

On March 20th the London Globe reported:

The Bolshevik occupation of Kherson and Nikolaieff [today Mikolayiv] was only effected after heavy fighting on the part of the French troops, who had, however, eventually to evacuate the towns and were transported by sea to Odesa. The German garrisons left behind apparently made no opposition, and even handed over their arms and fraternised with the Bolsheviks.

Odesa

French intervention in Ukraine, meanwhile, followed no clear policy.

They arrived in Odesa, fought and killed the local Ukrainian Rada troops who had just prevailed over the Hetman, and took over the city in collaboration with Whites who had landed by sea. As we have seen, at first they fought alongside the Hetman, the German puppet, until his regime died a death. For a long time after that the French ignored the Rada, because they were German collaborators (yeah, I know!). At the last possible moment, right before the Reds took Kyiv, the French recognised the Rada. It was too late to be of any use to either the French or the Rada, but it was in plenty of time to anger the White Volunteer Army under Denikin.

The French soldier met the Reds not just on the battlefield, but in the cafés and bars and on the streets. We have seen how the Red advance across Ukraine was sweeping but precarious. But in the cities the Communists were in their element. Odesa especially was a hotbed of fraternisation between Reds and Allied soldiers.

Written appeals once again give us a sense of what was said in their discussions:

Demand your immediate return home! And if your leaders don’t agree to send you back home, then organise your own return! Go back home and work with all your strength at the great task begun by the Russian Revolution, which will guarantee to the proletarians of the whole world, together with freedom and dignity, a greater well-being and happiness. Long live the soldiers’ and sailors’ soviets!

French officers grew scared at the influence of Red agents. They warned that ‘robbers, murderers, and Bolshevik agitators will be shot on the spot.’[i]

They were as good as their word. Ivan Smirnov, the leader of the Odesa communists, was tortured and shot by the French military. A French teacher named Jeanne Labourbe, who had been won over to communism and helped the Reds in their fraternisation efforts, was arrested. French officers and White Russians tortured and then shot her, along with ten of her comrades – five men, five women.[ii]

By the end of March Odesa was ‘without food and in a state of virtual anarchy.’ The Red Guards were outside the city. No doubt the presence of Red sabres and rifles helped to focus minds. But the French were troubled by their friends as well as their adversaries. The large Jewish population in Odesa brought into stark relief the anti-Semitism among the Whites and the Ukrainian nationalists. Anti-Semitism was no stranger to the France of the Dreyfus affair, but the massacres which had begun would have shocked the French soldiers, and posed once again the question of what they were doing there.

The French top brass made the decision to quit Odesa without consulting Denikin. The evacuation was a complete disaster, characterised by mass panic. The Reds were entering the city and the French troops were, in places, refusing to fight or even sabotaging the defence. 10,000 Russian Whites and 30,000 civilians crowded onto the Allied ships, including 8,000 of the Greek community in Odesa.[iii]

French military personnel embarked on April 5th. Entire units marched to the ships singing the ‘Internationale.’

But the real mutiny, that is, the one that our historians deign to mention, had not even begun.

Historian Evan Mawdsley makes a strange remark about the evacuation of Odesa: ‘The French did not leave – as is sometimes suggested – because of a naval mutiny; this came three weeks afterward.’[iv]

It was two weeks. More importantly, Mawdsley’s remark neglects to take into account the whole cycle of fraternisation and mutiny which we have just described. And after evacuating Odesa the French just sailed a little ways down the coast and invaded Sevastopol. Intervention was not finished after the Odesa evacuation.

Anger in the fleet

On April 16th, in the Romanian port of Galaţi, a plot was unfolding on board the French vessel Protet. This vessel had quit Odesa just a few days before.

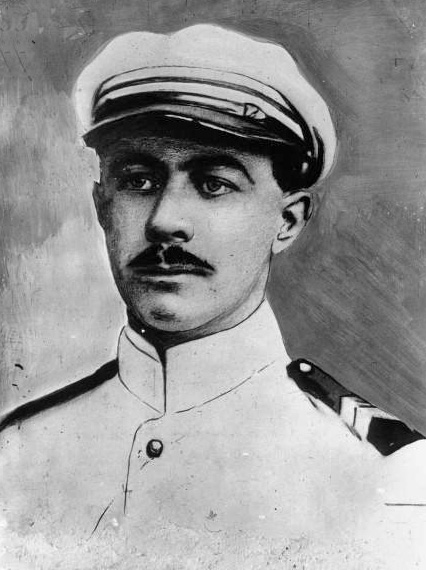

André Marty, who was on board the Protet, believed that mutiny was ‘the most sacred of duties.’ By attacking Russia without a declaration of war the French fleet was violating the constitution. Marty, an engineer, planned to seize the Protet and take it to Odesa under the red flag. His conspiracy was betrayed by informers, and he was arrested.

But discontent in the French fleet was not confined to the Protet or to Marty’s circle of conspirators. Throughout the fleet, the sailors were ready to revolt. They had been deeply effected by the experience in Odesa, and unknown sailors had even composed the Odesa Song which had caught on throughout the fleet.

After eight days on the high seas

We’ve arrived at last in Odessa town.

The Russians celebrated the went

With cannon and vintovka shots.

We were made to join the Volunteers,

A corps made up of officers,

So that we would our brothers fight

For the Bolsheviks are workers all.

You who run the show

Because you’ve got the dough

And piles of stocks and bonds,

If you want the cash,

Make haste to embark,

Ye capitalists

For the true poilus,

Those who fought in the war,

Are determined today

Not to fight any more,

Nor their brothers to kill

Or by them be killed.

The song goes on to promise to bring the Russian Revolution home to Clemenceau and to the French ruling class.

The sailors also knew and sang the ‘Hymn to the 17th’ – a song about a French military unit sent to crush a strike in 1907, who mutinied in protest.

The grievances of the sailors of 1919 are best summed up in the demands they would soon raise during the mutiny:

1. An end to the war against Russia.

2. Immediate return to France.

3. Less rigorous discipline.

4. Improved food.

5. Leave for the crew.

A list of demands raised by a different group of sailors raised similar points:

Immediate return to France.

Better food.

Display in all artillery emplacements of all news picked up by radio.

Demobilisation of reservists.

Immediate putting ashore of the master-at-arms.

Leave to be granted in a regular order.

As these grievances simmered, action committees were organised on most of the French warships. Petty officers and engineers were the leaders in this underground work. There was an anti-war socialist newspaper called ‘The Wave’ which reportedly had a circulation of 300,000 within the fleet. Every issue had a page of correspondence from ordinary sailors airing their grievances. It was banned, and officers would confiscate it on sight. But often the orderlies would steal it back for the sailors. Cuttings from the paper were hidden inside the right-wing newspapers. There were besides The Wave at least five other underground papers in regular circulation in the fleet.

Sevastopol: mutiny on the ships

Scene: the battleship France, a vessel 166 metres long and 27 wide, with over 1100 men on board. It is April 16th, and eleven days after evacuating Odesa the France sails in the outer harbour of Sevastopol, a port on the west coast of the Crimean peninsula.

A mechanical engineer named Vinciguerra maintains an underground library of socialist books, papers and pamphlets. He is at the centre of a group of twenty or thirty members of leftist organisations, most of an anarchist persuasion. This group exerts an influence over a great part of the crew.

In 1918 the ministers of the Crimean Soviet Republic were massacred in a Tatar uprising.[v] But by April 1919 the Reds have returned to Crimea, and they are advancing on Sevastopol.

The France, lying in the outer harbour, opens fire with its artillery and sends ashore landing parties to block the Red advance.

On April 17th the crew are called to man the guns. Many hide out in the latrines and refuse to leave; the officers are forced to man the guns on their own. Three French ships fire explosive shells at the Reds all night – so much for the end of the French intervention.[vi] The Reds are forced to retreat. In the morning, the ringleaders of the protest are locked up.

The sailors are informed that they will have to load coal on Easter Sunday, April 20th. This is a laborious task for a holiday, and it is greeted with anger. This is the trigger for the rebellion.

The word goes around the vessel: ‘Those who don’t want to carry coal, assemble on the forecastle, after the piping to quarters in the evening.’

On April 19th, almost all the crew gather on the forecastle for a protest. Things start out with an innocent appearance, but then the Odesa Song is sung. When the strains of the Internationale carry across the water, the crew of the neighbouring vessel, the Jean-Bart, joins in. The 600 on the deck of the France and many of the crew of the Jean-Bart join together in the chorus:

C’est la lutte finale

Groupons-nous et demain

L’Internationale

Sera le genre humain…

The officers, terrified, gather and arm themselves. They are right to be afraid. The sailors storm the prison cells and release their comrades. They take the steam-launch to the Jean-Bart and raise the crew in revolt.

‘To Toulon! No more war against the Russians!’ ‘Rise up! Rise up! Revolution!’

An unsigned article in the journal Revolutionary History takes up the story:

Vice-Admiral Amet, the commander of the fleet, arrived on board the France. Sailors and the Admiral stood face to face. The Admiral’s sermon was interrupted by shouts of ‘Take him away! Kill him!’ When he claimed that the Bolsheviks were bandits, a mutineer shouted at him: ‘You’re the biggest bandit.’ […]

On the Jean-Bart, Amet and the officers bring up great containers of wine in the hopes that the sailors will drink themselves into a stupor. But the sailors place a guard around the wine, and nobody touches a drop.

André Marty writes:

‘Practially every sailor on the France and the Jean-Bart was standing on the vast forecastle heads of the battleships, and, instead of saluting the tricolour being raised on the stern, they faced forward and sang the Internationale while the red flag was being hoisted on the bowsprit.’

An officer shouts, ‘You don’t know what that rag stands for, it means civil war!’

But to the sailors, it is obvious that the Russian Civil War has come on board their ship, not through any desire on their own part, but because their government and their officers are helping the Whites.

There is a moving scene when a Russian ship enters the harbour. It is called the Kherson, and its crew and passengers sympathise with the revolution. While the Kherson is in earshot of the French vessels, they join in a rendition of the Internationale.

At this point mutiny spreads to a fourth vessel, the Justice; the red flag is raised.

The commander is angry.

‘Who hoisted this rag?’

Silence.

‘It wasn’t hoisted by itself, was it?’

‘The entire crew is in on it,’ some of the sailors reply.

‘So I have a crew of Bolsheviks?’

‘We want to go back to France!’

Sevastopol: Mutiny in the streets

Instead of spending Easter Sunday loading coal, large numbers of mutineers go ashore. The city is occupied by Greek and French soldiers and sailors. The Greeks are tense, rifles ready; the French rank-and-file leave their weapons behind and mix with the civilian population. The French mutineers begin a march up Ekaterinskaya Street to the city centre. A group of local trade unionists meet them and present them with the banner of the metal workers’ union; behind that banner the crowd proceeds slowly through the streets, growing to two or three thousand, roughly one in ten of whom are French mutineers.

Outside the city hall they are greeted by the chair of the local Revolutionary Committee, who speaks fluent French; years ago he lived as an immigrant in Paris, working in a department store. He demands the evacuation of the military forces from the city and the transfer of power to the Soviet. The applause is enthusiastic. A French sailor from the crowd speaks in reply, assuring the chairman of the sympathy and support of the French sailors.

The march continues, growing further in size as sailors from all the ships join in. A French officer approaches the crowd and tries to seize the red banner of the metal workers. After a bit of shouting, he is sent packing with a slap to the face.

Retribution is sudden. A French Lieutenant gathers a group of Greek soldiers and a small number of French sailors from the Jean-Bart. Theytake cover on Morskaya Street. As the crowd crests arise, machine-guns and rifles open fire. The demonstration scatters into the side-streets, leaving many dead and wounded lying on the street.

The banner-bearer, a helmsman from the Vergniaud, mortally wounded by a bullet, lay on the ground covered by the red banner he had been carrying. A petty officer, a brave man, who had continued shouting “Forwardl Death to the dogs!” also fell mortally wounded and lay beside a young girl of sixteen who had been killed outright.[vii]

Victory

The Black Sea mutiny could have gone further, and very nearly did.

So enraged were the sailors by the massacre that French and Greek personnel were inches away from a pitched battle. The French did not, as one of my sources claims, open fire on the Greek flagship.[viii] But this was only because the officers and mates rushed to sabotage the guns before the sailors could lay a hand on them. On land, one party of French sailors had to be held back at gunpoint by their own officers, otherwise they would have gone to fight the Greek soldiers.

But the furious reaction to the massacre appears to have shaken the officers. The French Lieutenant who gave the order to shoot on Morskaya Street killed himself that very night. This saved the top brass some embarrassment. It is easier to make a scapegoat out of a dead man.

The sailors were in control of the ships, and in close contact with the soldiers. They held the power. But the officers were smart enough to bend rather than break. They promised that the ships would go home. They promised that there would be no reprisals.

Several days later, the ships quit Sevastopol and sailed home. In spite of the solemn promises of the officers, the ‘ringleaders’ of the mutiny were later arrested and sentenced.

The next vessel to erupt in protest was the Waldeck-Rousseau, back at Odessa. When the prisoner André Marty was brought on board, sailors rallied and sang the Internationale. There were further mutinies at nearby Tendra and on the torpedo boat Dehorter at Kerch.

Unrest in the French fleet carried on unabated all through the summer of 1919 and all through the Mediterranean. Rebellion flared up at Toulon, the main French naval base, with protests in the streets and unrest on the ships in the harbour. Sailors held stormy mass meetings on the glacis of the fort. For several days the town was practically under the control of protestors. From June 12th to 17th the rebellion was discussed in the French parliament.

From the first scouting party advancing on Tiraspol to the revolutionary events in Sevastopol and all the way back to French soil, the war effort in Ukraine and Russia was sabotaged by French sailors and soldiers. It must have sorely hurt the pride of the politicians and generals and admirals that their rank-and-file had revolted under the red flag – the symbol of the very regime they had been sent to help crush.

France had been the most aggressive of the western Allied powers. But the French soldier and sailor forced all the Allied leaders to recognise that if they pushed their luck in Russia and Ukraine, they would face troubles not just among their own soldiers but on their own streets. On the British side, there was the Calais Soviet, the soldiers’ protest in London, and the rapid spread of the ideas of the Russian Revolution in Ireland and Scotland.

France was forced to drop its policy of intervention in favour of a cordon sanitaire: besieging Soviet Russia in a ring of hostile states armed and funded by France. This policy would bear fruit in the Polish-Soviet War of 1920, which we will look at in Series Three.

What about all those mutineers who were arrested? They were harshly sentenced, but some years later, after a public campaign, they were amnestied and released.

On May 1st 1919, Sevastopol celebrated its liberation. It was a triumph not of arms, but of ideas, and not of combat but of fraternisation. The revolutionaries of many nationalities who made this victory wrote an important chapter in the history of revolutionary warfare – a chapter which, in most English-language accounts published in the last few decades, is reduced to a dismissive sentence or two.

The defeat of the French intervention in south-west Ukraine and Crimea was achieved with the most humanistic methods: through finding common cause with the enemy combatants, rather than by shooting at them. It was no less decisive for that. The new Soviet regime held a new and powerful weapon in its hands: the power of the class appeal. The Black Sea revolt represents the most outstanding example of mutiny and fraternisation, but it was a general feature of the Russian Civil War, and an inspiring one.

Go to Revolution Under Siege Archive

Sources

Most of the above is drawn from these sources:

- ‘The Black Sea Revolt’ from Revolutionary History:

https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/revhist/backiss/vol8/no2/blacksea.html

- ‘During the Black Sea Mutiny, French Sailors rejected France’s war on Soviet Russia,’ from Jacobin:

https://jacobin.com/2020/12/black-sea-mutinies-france-sailors-soviet-russia

- The Epic of the Black Sea Revolt by André Marty:

https://stars.library.ucf.edu/prism/821/

[i] The Globe, February 13th 1919

[ii] André Marty, The Epic of the Black Sea Revolt, (See Above) p 8

[iii] Anthony Read, The World on Fire, Jonathan Cape, 2008, p 164

[iv] Mawdsley, 178

[v] Mawdsley, 48

[vi] Marty, 28

[vii] Marty, 41

[viii] Read, 164