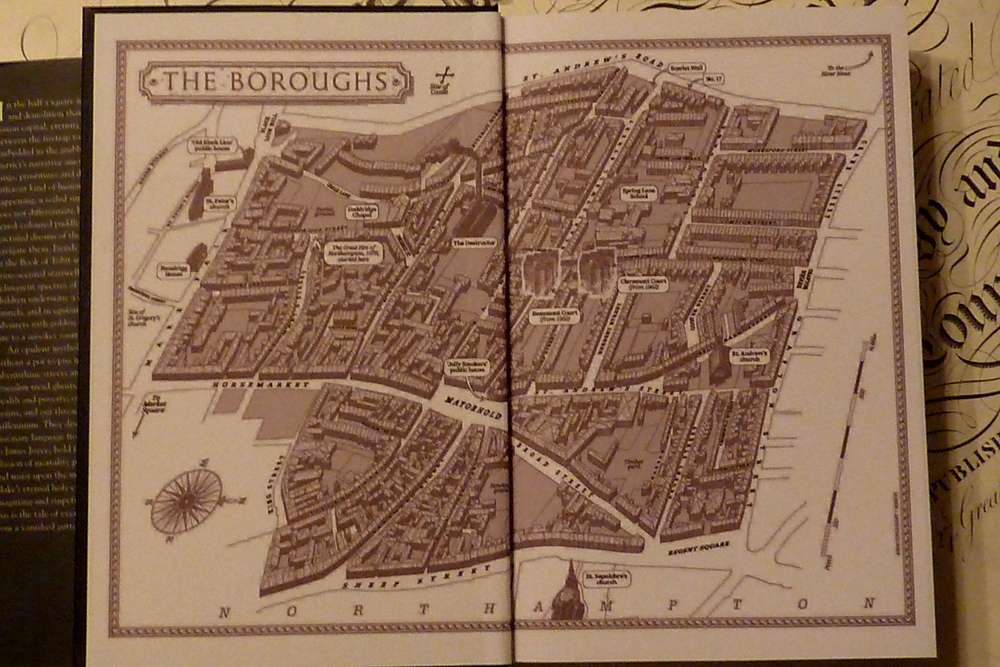

Alan Moore’s 2016 novel Jerusalem is a heartfelt, sprawling tribute to the Boroughs, a Northampton neighbourhood with a seedy present but an illustrious past. For the author, Northampton is nothing less than Jerusalem, the Jerusalem of William Blake. Or it might have been, but it’s too late now.

The story centres around Alma and Mick Warren, a sister and brother who grow up in the Boroughs. Alma becomes a brilliant but utterly demented artist, Mick a manual worker. In 2005 Mick has a workplace accident that triggers a flashback to his childhood, to a near-death experience that sent his spirit on an adventure in the afterlife. This plane of existence, neither heaven nor hell, is a version of the Boroughs that exists beyond space and time. By combing through these memories, Mick and Alma come to understand the forces both supernatural and mundane working to grind the neighbourhood into oblivion.

In a long flashback, toddler Michael wanders into the afterlife and falls in with a gang of ghostly kids, the Dead Dead Gang, who resemble something out of Enid Blyton. Of course, these innocent pranksters are all dead – some of them died as children, others lived full lives but choose to live as kids in the afterlife. After these adventures come to a triumphant conclusion, we return to the present. It’s time for Alma to attempt to save the Boroughs.

The Destructor

But in Jerusalem, time is simply another dimension (thus trees are four-dimensional structures), free will is an illusion, and all the moments of our lives happen simultaneously in a coruscating eternity (as Doctor Manhattan once explained). After death we ascend to an eternal plane from which we view our lives from above and outside, as it were. It seems to be a kind of superstructure based on and growing out of the real world; as below, so above. But what takes shape in the superstructure can rebound upon the base, as we see with the Destructor, a sinister vortex at the rotting heart of the Boroughs. This huge waste incinerator dominated the neighbourhood for years, an example of the contempt of the authorities for the health and wellbeing of the folks living nearby. This act of state cruelty continues to exert a dire cosmic influence long after the Destructor itself is demolished.

It’s a good thing there’s an eternal afterlife where our deeds and creations are inscribed forever, since the story is all about the slow and painful death of a neighbourhood. The story is told through a wide range of characters, dead and alive, who criss-cross the Boroughs in many dimensions, striking one another and rebounding unpredictably like the billiard (trilliard) balls of the male proletarian ‘vaguely Soviet’ angels who run the show.

‘Lacking restraint?’

If you don’t like a book that can be described as ‘challenging and at times lacking restraint’, then Jerusalem is not for you. But ‘lacking restraint’ is a quality essential to this type of story.

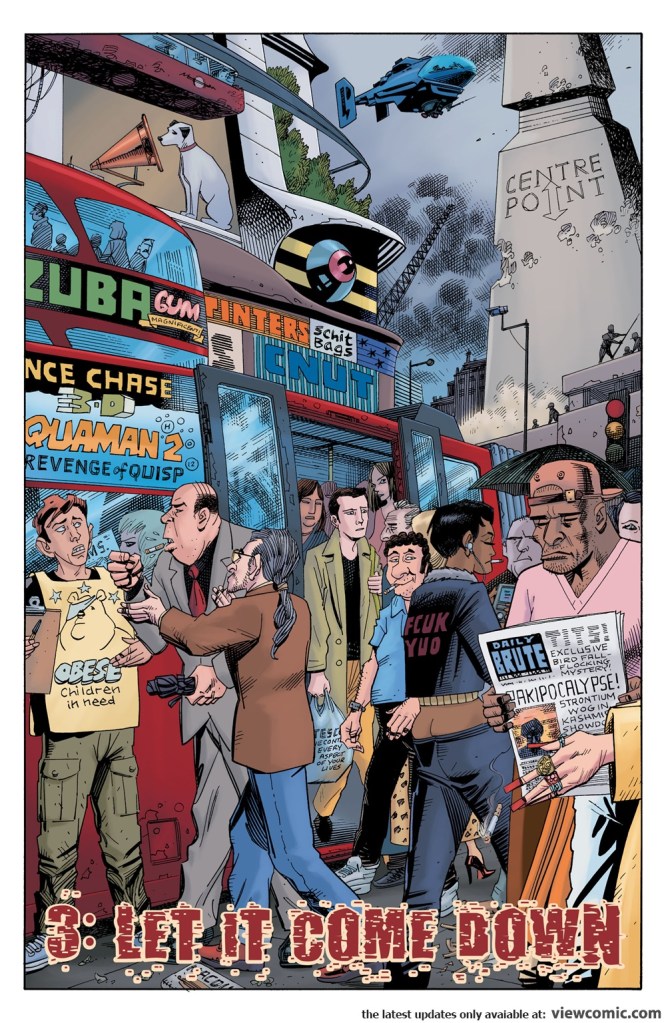

Like his creation Alma Warren, Alan Moore can be exasperating. I lost my patience with him a few years ago when I bought a League of Extraordinary Gentlemen graphic novel only to open it and find that it was half in German. For feck’s sake! I wasn’t going to read a comic with Google translate open on my phone, just so I could read speech bubbles full of references that would probably go over my head anyway.

But since making the pilgrimage to Jerusalem, I’ve re-read the brilliant League saga titled Century. Like Jerusalem, it portrays the 2000s as an irredeemable sadistic miserable dystopia, with social conditions that remind Mina Murray of the Victorian era, but weighed down with even more hopelessness and cynicism. That portrait will stand the test of time.

No part of Jerusalem alienated, annoyed or baffled me – with one exception. There was a sequence of chapters narrated by Lucia Joyce in (what I assume is) Finnegan’s Wake-style gibberish. Maybe it was just the effect of listening on audiobook, but it drove me mad. I almost never skip parts of books, but after enduring the babble for a while I skipped it.

Jerusalem takes place almost entirely in Northampton (including Lambeth; Moore claims that Lambeth is an annex or honorary part of the Boroughs). But the scope is far from narrow, taking in Sierra Leone and the United States, the world economy, climate change, the ‘war on terror’, epidemics, slavery, woolly mammoths and a trek into the furthest reaches of the future.

Along the way the reader learns about everything from Northampton’s religious conflicts to the illustrious inhabitants of its mental institutions, including the aforementioned Lucia Joyce. Even if it ‘lacks self-restraint,’ Jerusalem is not self-indulgent; Moore is conscientious and reverent concerning details of local and social history, from death-mongers to the origin of the name ‘Scarletwell Street.’ If anything it is Boroughs-indulgent.

Putting Northampton on the Map?

There’s an episode of Alan Partridge in which Alan tries to pitch a show idea to TV executives: ‘this TV show will put Norwich on the map!’

To which the TV guys respond, ‘Why would we want to put Norwich on the map?’

Why would readers want to immerse themselves in the past, present and future of Northampton? Why did I, in essence, go on a hungover sixty-hour walking tour of the Boroughs with Alan Moore as my tour guide? Why did I enjoy it so much, and get so much out of it?

One answer lies in the architecture of Moore’s heaven. Between life and afterlife lies the ‘ghost seam,’ a monochrome world in which those who are unable or unwilling to move on from the sins and traumas of their lives are doomed to wander. In a memorable scene, Moore notes that ghosts are rare in the Boroughs but common in the leafy suburbs – snobs from the professional classes lingering in their back gardens, unable to leave behind their property, making bitter remarks about the South Asians who have moved into their houses. Castles and mansions are, as everyone knows, teeming with ghosts and madness. But the humble folk of the Boroughs ascend without difficulty to a radiant and glorious eternity. The working class in general gets the express service to heaven. Jerusalem is more broadly a celebration of working-class life. Again and again, the language and imagery link the working class with the divine, the angelic, cathedrals and paradise.

Demons feature in the story, but they are relatively harmless. The real evil is the faceless, destructive horror of capitalism. The acts of violence in the book – from sexual assault to socio-economic violence (I’m aware that the implied metaphor is problematic) – are all inspired by a world-view that sees human beings as selfish units with no obligations or connections to one another. The despicable Labour politician Jim Cockie sees the misery in the Boroughs as a phenomenon rooted in ‘individual responsibility’ rather than oppression. For more on this, take a look at this very insightful write-up by David M Higgins.

The antidote to this is a bizarre art exhibition hosted by Alma Warren which serves as a kind of inquest, pointing the finger of blame while also celebrating the neighbourhood. Reminding us of the place we occupy in eternity makes the world a more interesting and colourful place, gives layer and texture to our surroundings, renders them comprehensible and legible. But more than that: it empowers us to make a political challenge.

Moore tells a story about his home town, and similar stories could be told about the towns I know. But it doesn’t matter what town it is. What matters is having human connections to a place and to those who live there (even if like ‘Black Charlie’ you originally came there from the other side of the world), being immersed in the art that was created there, appreciating the destruction that has been wrought there, seeing the past and the future embodied in the present. Jerusalem spoke to me because while it’s all about the uniqueness and specificity of Northampton, the same could apply to the run-down neighbourhoods and ghost-town streets near my house or yours.