This episode tells how the warlord Grigoriev in Ukraine led a bloody revolt against the Soviet power. The episode will then describe his fatal showdown with the anarchist Nestor Makhno.

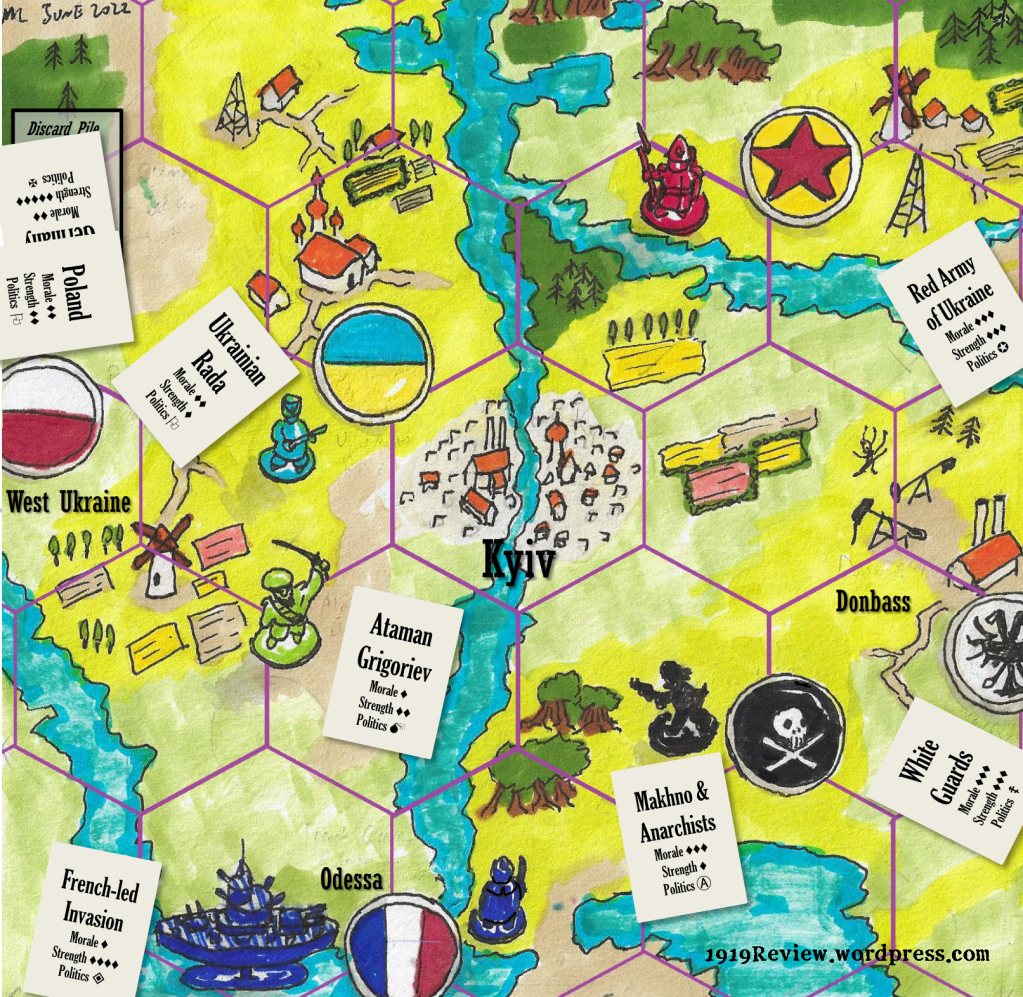

‘Anarchy’ means ‘without rulers,’ not ‘without order’ or ‘without laws.’ Still the word is often used to signify chaos. Here we can sidestep the controversy, because the word applies in both senses to Ukraine in 1919. The title of this post refers to the Anarchist army which operated in Ukraine at this time, ‘a singing army which moved in carts – a machine-gun and an accordion in each cart – under black banners.’[i] But it also refers to the state of chaos and violence which prevailed in many parts of the country and under flags of all colours – not just black. By May, ‘villages turned in on themselves’ for protection, ‘while armed bands roamed the countryside, led by warlords.’[ii]

Grigoriev in Odesa

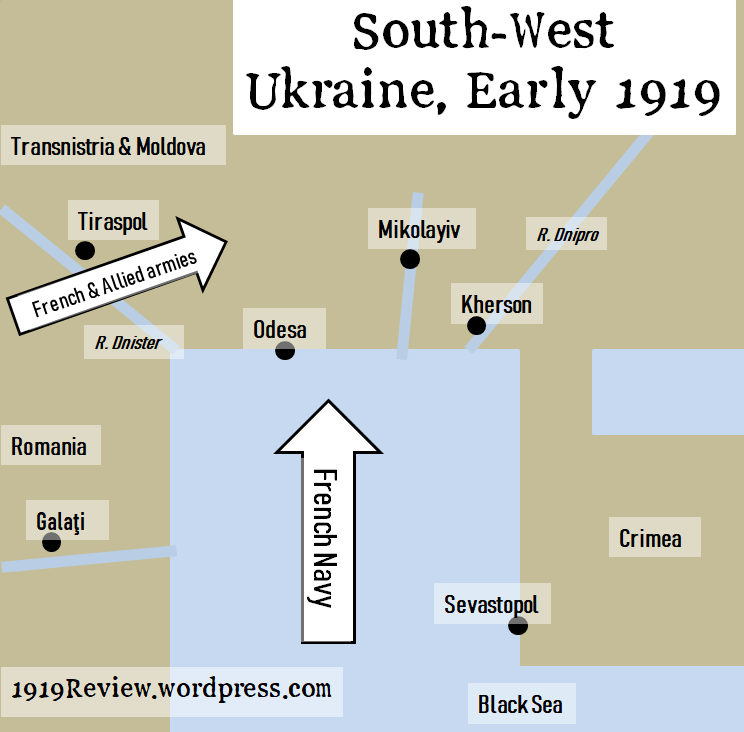

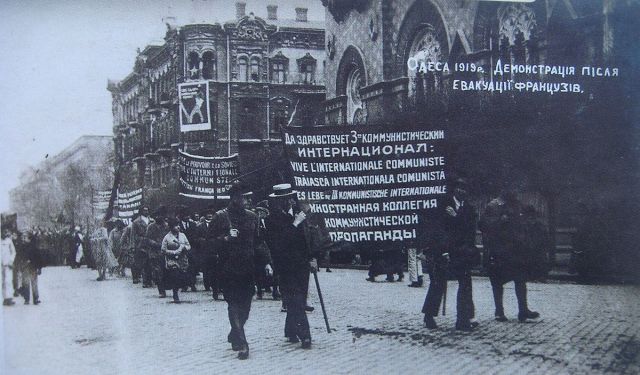

When last this series covered events in the great port city of Odesa, it was in a state of utter chaos with the evacuation of Allied interventionists. Reds were already marching in.

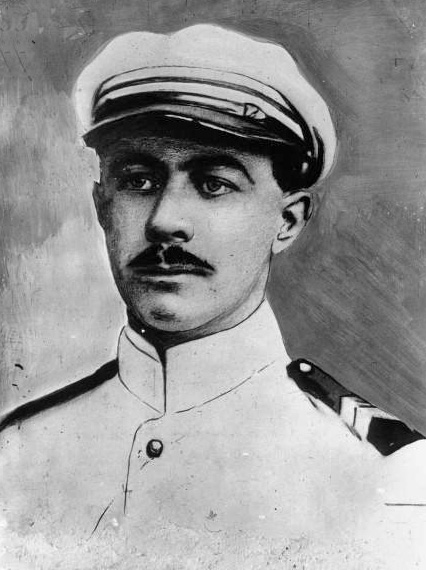

A Red commander reported to Moscow that the city had been taken ‘exclusively’ by the forces of the charismatic partisan leader Nikifor Grigoriev. These fighters had shown ‘revolutionary stamina’ and Grigoriev had led from the front: he had two horses shot from under him, and bullet holes in his uniform. But on the day before the fall of Odesa he was taking a well-earned break: he spent the day drinking from a bucket of wine and listening to the regimental band.[iii]

Odesa was a wealthy city, and in 1919 its warehouses were bursting with the goods and equipment which the Allies had left behind in the chaos of their evacuation. Grigoriev made himself a kingly giver of gifts in relation to all this loot – for example, 30,000 rifles were apparently sent to the villages of the Kherson region. There is also a story that he looted hundreds of kilograms of gold from the Odesa State Bank.[iv]

The local Communists – those who had fraternised with the French in the cafés – celebrated the liberation. But very soon the city’s revolutionary committee was addressing complaints to the warlord about his claiming of the loot.

‘… I occupied Odessa,’ he later told Makhno, ‘from where the Jewish Revolutionary Committee appeared. They came to my headquarters … They began to demand that [I obey them], that the lads stop beating the Jews. And you know, people on the campaign were torn, worn out, and there are a lot of Jewish speculators in the city […] I took the city, therefore, it is mine, and then the Revolutionary Committee crawled out of the underground and stood in my way, talking about submission. When I attacked, there wasn’t a single member of the Revolutionary Committee with me, but now, you see, they decided to be the boss.’

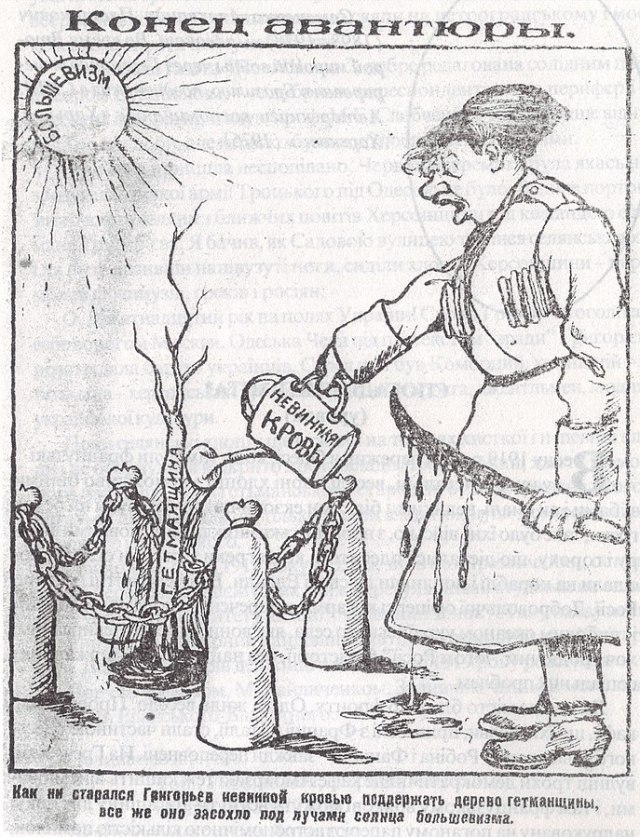

He was just boasting. But the eyes of the Soviet government were not blind to the problems Grigoriev might present. He had switched sides three times already. He gave lip-service to communism but anti-Semitic slogans were current among his supporters. Yet he had driven the Allied interventionists right out of Ukraine. The Soviet government awarded him the Order of the Red Banner for this triumph.

After ten days in Odesa, local communists were already demanding that Grigoriev be arrested. A bloody clash appeared inevitable. But Grigoriev and his forces withdrew to the villages near Kropvynitsi (then known as Elizavetgrad). To give you a sense of the distance, today that’s a five-hour drive inland.

Grigoriev in Budapest?

As summer approached, the Soviet laid plans to have Grigoriev carry the banner of the October Revolution to the very heart of Europe. The Hungarian Soviet Republic was isolated and under attack. Grigoriev’s force was, on paper, a short distance from Hungary: just charge right through Transnistria and Romania (Or through Poland and Slovakia), and boom, there you are. But the problems are so obvious that one is forced to wonder what the hell the Soviet leaders were thinking. Grigoriev was not exactly the ideal ambassador for communism, and once he’d seized Budapest he might well change sides again. He was a partisan leader, not a rounded-out military genius, and such an ambitious attack was likely beyond his capabilities. Maybe the Soviet government was desperate (We have to help the Hungarian comrades, no matter the cost or the risks!) or maybe they were cynical (this might keep Grigoriev out of trouble – and with any luck he won’t come back alive) or maybe some mixture of the two was at work. At the very least Grigoriev might divert Romanian forces and take the pressure off Soviet Hungary.

For better or for worse, probably for better, it never happened. Grigoriev switched sides again. He had turned from Rada to Hetman and back again, before turning to the Reds. Now he struck out on his own, backed by tens of thousands of armed soldiers and by a large part of the Ukrainian farming classes.

Grigoriev in Revolt

When is an ataman officially in revolt? When does he cross the line? He always has plausible deniability, because he is not fully in control of his forces. Many Communists, such as Antonov-Ovseenko, were in denial about his revolt at first.

By his own account, his revolt developed organically as a response to overbearing communists: ‘My troops could not stand it and began to beat the [Cheka] themselves and chase the commissars. All my statements to Rakovsky and Antonov ended only with the dispatch of commissars. [Eventually] I just kicked them out the door.’

From the communists’ perspective, Grigoriev had been operating as a law unto himself for too long. Soviet government officials were allowed no authority on his territory, and many communists were quietly murdered. One commissar ordered to go to strike a deal with Grigoriev refused, citing poor health. But it is obvious the commissar was in fear for his life, with good reason.

On May 1st a Grigoriev armoured train celebrated International Workers’ Day by firing explosive shells into Kropvynitsi. Over the next week, anti-Jewish and anti-communist pogroms swept through the local area. On May 7th a Red commander threatened to attack Grigoriev if the pogroms did not stop. On the same day several Chekists boarded Grigoriev’s armoured train and tried to arrest him. They were themselves captured and later shot.

On May 8th (one month after literally riding into Odesa on a white horse), Grigoriev published a manifesto titled the ‘First Universal.’ It was no longer possible to doubt his intentions.

It was a forceful appeal to the Ukrainian farmer. It began by recounting the horrors of the Great War and German occupation before moving on to those of the Civil War. It blames the ‘Muscovites’ and those ‘from the land where Christ was crucified.’

‘Those who promise you a bright future exploit you! They fight you with weapons in their hands, take your bread, requisition your cattle and assure you that all this is for the benefit of the people. Hard-working, holy man of God! Look at your calloused hands, look: all around – untruth, lies and insults […] You are the Feeder of the World, but you are a slave.’

He called for soviets but without communists, along with representative bodies where the majority of seats would be reserved for Ukrainians. He demanded that the Ukrainian Soviet government ‘leave us’ and summoned each village to send fighters to Kyiv and to Kharkiv – with weapons, and if there were no weapons to hand, with pitchforks.

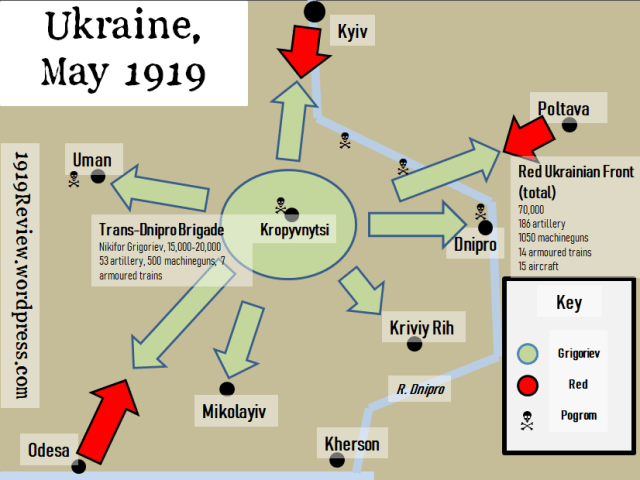

By May 10th there was no longer any pretense or hesitation. Grigoriev’s army, which was between 16,000 and 20,000-strong, had risen up against Soviet Ukraine, with armed columns speeding out in all directions from Kropyvnitsi.

What did this revolt look like? A Grigorievite column would ride into town by horse or by train, or a Red garrison would declare for Grigoriev; usually a combination of the two – for example at Kremenchug, Chigirin, Zolotonosha and Cherkasy. In Pavlograd the Red Army soldiers revolted of their own accord. In Dnipro anarchists and sailors went over to Grigoriev and handed him the city. In all, about 8,000 Red Army soldiers went over to Grigoriev.

Soviet officials would be shot. Jews would be robbed, violated, killed. Prisons would be opened. In Kropyvnitsi, epicentre of the revolt, we see all of the above on May 15th: a pogrom which killed 3-4,000 Jews and several hundred Russians. Some of the murderers were those who had deserted from the Red Army. In other towns and villages, we see hundreds killed here, thousands killed there. According to Savchenko: ‘The commanders of the Grigorievites in Cherkassy urged each insurgent to kill at least 15 Jews. An eyewitness writes: “There is no street in Cherkassy where families have not been killed. Russians and Jews were dying… indiscriminately.”’

Dnipro was briefly recaptured by the Reds, and they executed one out of every ten ten of the captured Grigorievites. But in short order the other nine out of ten revolted in prison, and again took over the city.

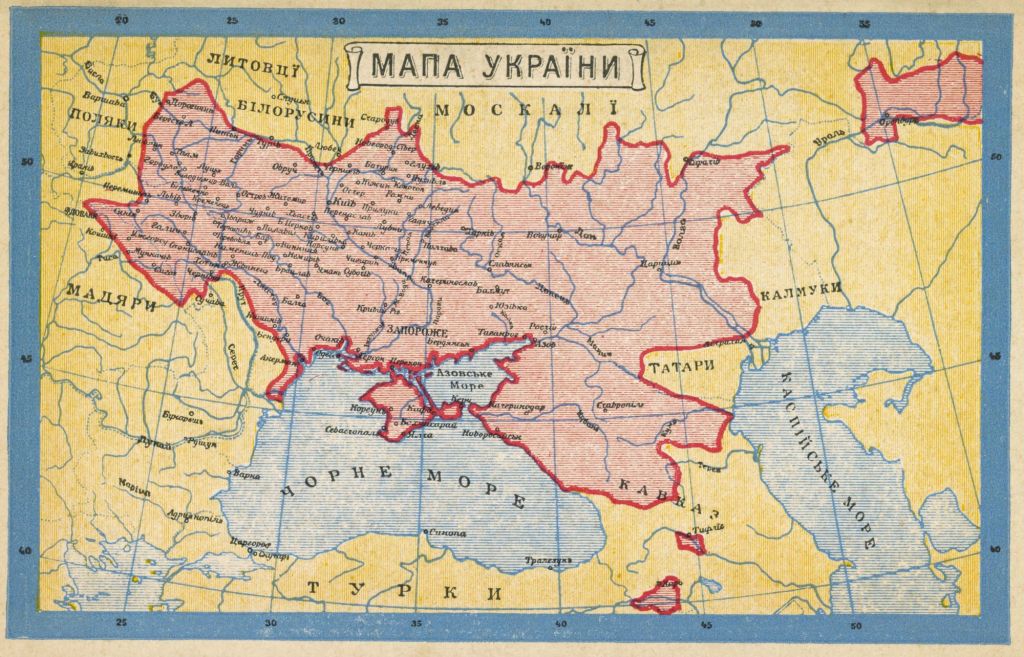

What was the scope of the revolt? The Dnipro River runs through the heart of Ukraine, and within two weeks the Grigorievites had taken over the middle third of that river. Roughly speaking, their power stretched 100-200km wide to the west side of the river and 50-100km to the east, in places much further. At their furthest advance, they came within 80km of Kyiv and 20 of Poltava.

There was a considerable crossover between Grigoriev’s base and Makhno’s, and as we have seen some anarchists joined the revolt. But Makhno resisted any pressure to join Grigoriev, and stayed with the Red Army, though he denounced the latter as ‘political charlatans’ and condemned the ‘feud for power’ between the two.

The Ukrainian Soviet Government

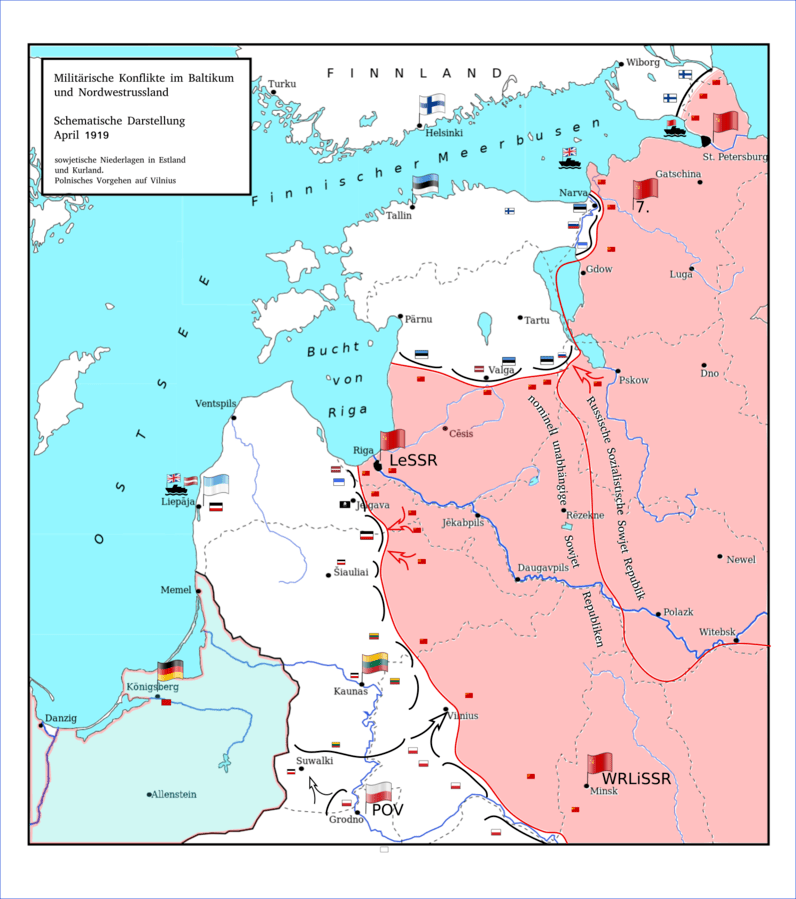

The Ukrainian Soviet government under Yuri Pyatakov, and even its more moderate successor under Christian Rakovsky, had in many ways sown the seeds of the Grigoriev revolt. There were trigger-happy Chekists gunning down innocent people, Red Army units looting villages, and there was the same grain requisitioning that had angered the Russian peasants. Pushing Ukraine over the edge were the same ultra-left policies on the land and the national question which had done so much damage in Latvia. The ‘First Universal’ complained about land nationalisation directly, with a complaint about the farmers being forced into a ‘commune.’

In an aside, it is customary at this point to lob a casual accusation that the Communists refused to cooperate with other parties, specifically the Borotbisti, who were the Ukrainian Left SRs. But Grigoriev himself was a Borotbist. His membership in the party was symptomatic of the unstable streak that was part of the Left SR DNA. It’s hardly fair to criticise the Communists for cooperating with a Borotbist and in the same breath to criticise them for not cooperating with the Borotbisti.[v]

It is tempting to present Grigoriev as a monster and to invite ridicule of his changing loyalties. Yes, as Golynkov says, he was politically illiterate and unprincipled.[vi] But a more nuanced interpretation comes from Timkov: that Grigoriev was a ‘hostage’ to his large and varied support base. ‘[I]n order to preserve his power, the chieftain had to wade into the chaos of the opinions and wishes of the peasant masses. You can say that he became their hostage.’[vii] He was, says Smele, ‘a complex and possibly unbalanced character’ and an ‘outrageous freebooter,’ but on the other hand he was ‘genuinely popular.’[viii]

His vacillations are more understandable as the vacillations of a large mass of people, not of one individual. And the wild character of these twists and turns – the turn from Rada to Hetman and back again, from Rada to Reds, from Reds to vicious pogroms – can be better understood as the throes of a mass of people in severe pain.

And we can’t blame all this pain on the mistakes of Soviet Ukraine. The Allies, the Whites, the Germans, the Rada and the Poles had all played their part as well. Further, regardless of specific mistakes or crimes by this or that force, the Grigoriev revolt was an outbreak of rage against the intolerable burdens which the Civil War had placed on rural communities in Ukraine. Partisan armies would have revolted against whoever was in charge, and later did revolt en masse against the Whites.

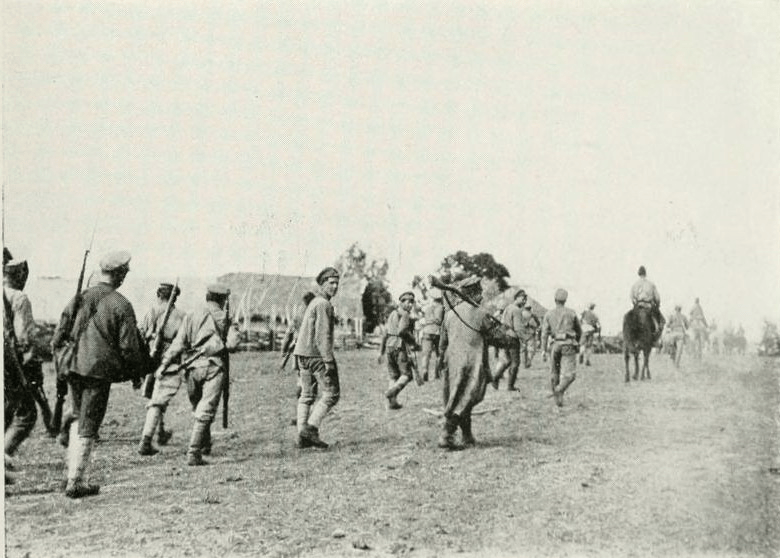

The Grigoriev revolt was a severe trial for the Ukrainian Red Army. As we have seen, this army was in a shambolic state. But a force of about 20,000 Ukrainians and 10,000 Russians was quickly assembled. Officials, communist youth members and members of the Jewish Socialist Bund all volunteered.

The revolt had spread like flames on petrol, but within a few weeks it had burned itself out. On May 14th large Red forces set out from Odesa, Kyiv and Poltava. Grigoriev’s all-out advance in all directions, meanwhile, was faltering. It seemed early on that his columns were advancing and conquering at lightning speed. In fact they were dispersing in all directions and disintegrating in the vast spaces of Ukraine. One by one the Red Army re-conquered the cities Grigoriev had taken, and in a series of battles in late May he lost 8,000 killed and wounded.

Grigoriev’s army disintegrated. The 3,000 who remained loyal switched to guerrilla warfare west of the Dnipro. While the Reds could declare complete victory, other local warlords had risen up in other parts of Ukraine, and Grigoriev could still raid towns, hold up trains, destroy railways.

The Whites Attack

Meanwhile the Whites had been well-positioned in the Donbass region, and in late May they had seized their moment. The White general Mai-Maevsky himself had warned his men not to underestimate Makhno’s Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine, the army on carts under the black flag of anarchism. Their partisan tactics had run rings around the Germans and the Whites. But in late May Mai-Maevsky’s forces struck deep into Ukraine. The Whites simply cut through the Anarchists. The Black Army fled, like Grigoriev, to the western fringes of Ukraine. They had been reduced to 4,000 fighters.

Arshinov, an anarchist writing in 1923, presents this move as a stubborn fighting retreat.[ix] He claims that the Reds, by contrast, gave up Ukraine to the Whites without any fight-back at all. The first claim is probably an exaggeration, and the second is completely untrue. Trotsky’s armoured train rolled into the Mikolayiv-Kherson region (Trotsky’s own home turf where his dad still had a farm) and there tried to make a stand; Kharkiv was turned into a fortress; Iona Yakir led several divisions on one of those ‘Long Marches’ which so characterized the Civil War – a 300-mile fighting retreat which succeeded in preserving large forces from destruction.

The failure of Makhno’s Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine requires explanation. The Black Army was a partisan army, its military doctrine an extension of its political philosophy. There was no contradiction between Mai-Maevsky’s appreciation of its strengths and the ease with which the same general scattered it. Its strength lay in raids and mobility; it was utterly incapable of holding a line against a determined advance. At the very least this defeat represented a political and military failure for the Anarchists. For Moscow, it was nothing less than treachery, and Makhno was outlawed.

Warlords in Exile

West Ukraine was getting crowded with the remnants of defeated armies. The Anarchists were pursued there by the General Shkuro, a cunning and merciless Kuban Cossack whose personal bodyguard were known as the ‘Wolf Hundred.’

To survive the onslaught of the White Wolves, the Anarchists made a tactical alliance with the Rada forces of Semyon Petlyura who, like themselves and Grigoriev, had ended up west of the Dnipro. The alliance was short-lived. Arshinov says the Ukrainian Nationalists soon betrayed them, a development which all parties had anticipated.

Next Grigoriev came knocking on Makhno’s door. Though Makhno had previously condemned Grigoriev and his pogroms, he agreed to cooperate pending an investigation. They fought side-by-side for three weeks against the Reds.

Grigoriev, Makhno and other Ukrainian partisans – reportedly 20,000 in all[x] – gathered for a great congress on July 27th in a village near Oleksandriya. The supposed aim of this peasant congress was to unite an anti-Bolshevik army.

There are different versions of what happened next, which you can follow up and tease out in the sources. Here is my composite sketch:

The Grigoriev forces were camped outside the village, but the village itself was occupied by Makhno’s forces, the lanes dominated by his tachankas, machine-gun carts.

At the congress, the Makhnovist Chubenko stood up at the podium and denounced Grigoriev as a murderer of Jews and a hireling of the Whites. Grigoriev denied the charges and reached for one of his Mauser semi-automatic pistols. But he realized he was surrounded by armed anarchists. He placed the Mauser in the back of his boot and fled from the scene, intending to make an appeal to the village council. But he found Makhno and his lieutenants waiting for him at the house ofthe village council. Chubenko arrived and a heated argument began.

Some days before, the anarchists had captured some White officers who had letters addressed to Grigoriev. It was obvious from the letters that the ataman was planning to join with Denikin. Remember I mentioned Iona Yakir and his fighting retreat across Ukraine? It appears Shkuro and Grigoriev were planning together to catch and destroy the retreating Reds. The anarchists shot the captured White officers and kept this intel to themselves, for the time being. Now, at the congress of July 27th, they revealed it before 20,000 partisans.

Chubenko told the Soviet security forces later:

‘Grigoryev began to deny it, and I answered him: “And who and to whom did the officers whom Makhno shot come?”

‘As soon as I said this, Grigoriev grabbed the revolver, but I, being ready, shot point-blank at him.’

Grigoriev called to Makhno by his nickname: “Oh, father, father!”

‘Makhno shouted: “Beat the ataman!”

‘Grigoriev ran out of the room, and I followed him and shot him in the back all the time. He jumped out into the yard and fell. That’s when I finished him off.’

By other accounts, such chaos ensued when Grigoriev fled, with people running in all directions, that it was impossible to see who fired the fatal shot.

Makhno and his men shot down Grigoriev’s bodyguard, then went around the village to kill the ataman’s head honchos.

‘That was the sort of treatment I always reserved,’ Makhno later wrote, ‘for those who had carried out pogroms or were in the throes of preparing them.’

But why did the Anarchists ever collaborate with these pogromists in the first place? Arshinov explains that many of the mass following Grigoriev were genuine revolutionaries, who must be won over. The July 27th congress was in fact an elaborate trap for Grigoriev. It is even rumoured that someone had secretly emptied the bullets out of the ataman’s Mauser.

The Anarchists got what they wanted: the leadership of Grigoriev’s band was wiped out, but the rank-and-file joined the Black Army.

Another rumour has it that the gold reserves of the Odesa State Bank had been in Grigoriev’s train, and that Makhno’s men immediately rode out to seize it, then buried the gold a month later. The place where they are supposed to have buried the gold is near Kherson, not far from the frontline in the current war at the time of writing. If there is any gold around there, it’s under water as well as earth. Since the 1950s the area has been flooded by the Khakovsky reservoir. Maybe someone reading this will go on a mission to the heart of a warzone to look for Makhno’s Gold.

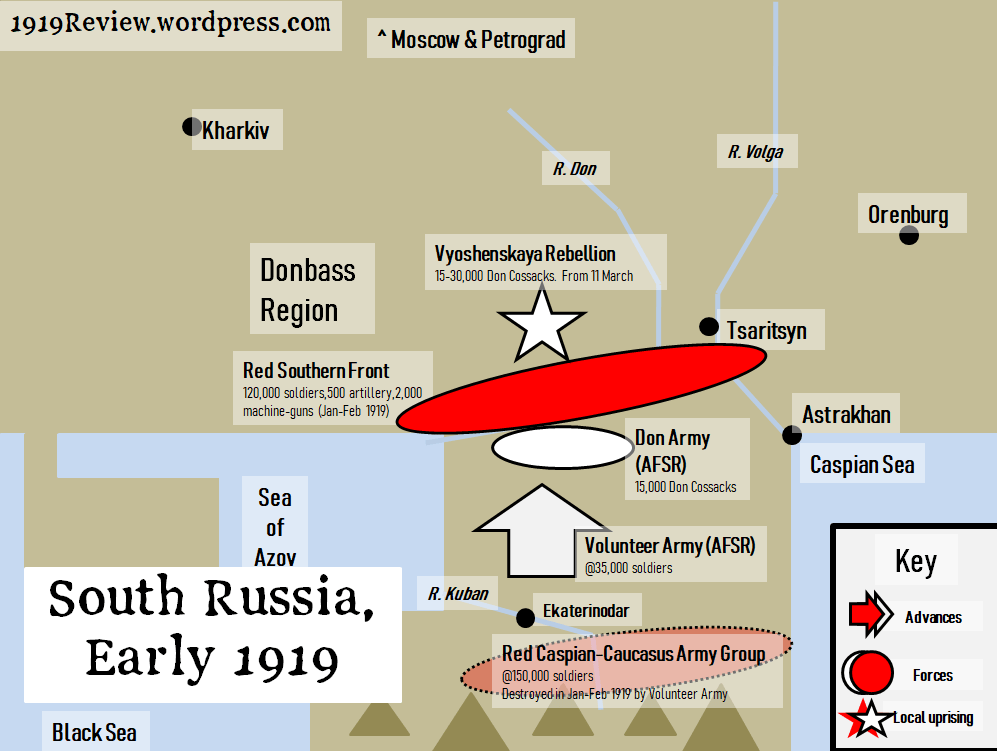

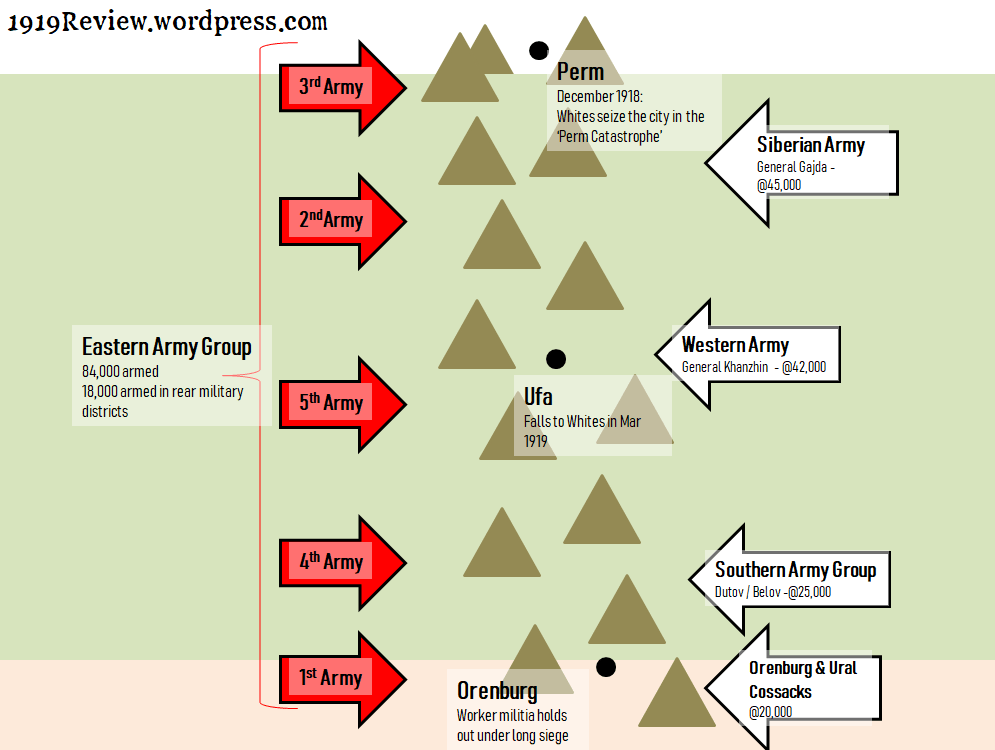

The Fall of Soviet Ukraine

That summer, Soviet Ukraine collapsed. In August, two weeks after Trotsky recorded that half of Red Army soldiers in Ukraine had no boots or underwear, Kyiv fell to the Whites.[xi] A number of factors which we have dealt with in the last few episodescame together to produce this collapse. The Don Cossack revolt in neighbouring South Russia, the pressure from Kolchak’s Spring Offensive, the Grigoriev revolt and the flight of the Anarchists all weakened the Red southern and Ukraine fronts. This set the stage for the defining campaign of the whole Civil War: Denikin’s march on Moscow.

Go to Revolution Under Siege Archive

[i] Serge, Conquered City, p 99

[ii] SA Smith, Russia in Revolution, p 186

[iii] Savchenko, ‘Ataman of Pogroms Grigoriev’, http://militera.lib.ru/bio/savchenko/04.html/index.html. Most of my information comes from this long and remarkable essay. That, unless otherwise stated, is generally the source for whatever detail or quote you may want to follow up.

[iv] From a source quoted on the blog of Alexandria Cossacks: https://kozactvo-jimdofree-com.translate.goog/%D1%83%D0%B2%D1%96%D1%87%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%BC%D0%BE-%D0%BF%D0%B0%D0%BC-%D1%8F%D1%82%D1%8C-%D0%BE%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%BC%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B0/?_x_tr_sl=auto&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=wapp

[v] On the Borotbisti more generally, my sources offer a sliding scale of sweeping statements. Supposedly the Communists merged with the Borotbisti, but also they banned them; they also, it seems, cooperated with them, all the while completely refusing to cooperate with them. I can only throw my hands up. Of course historians are supposed to summarise, employing their own interpretations. But in this case the same set of data produces completely contradictory interpretations. See EH Carr and SA Smith.

[vi] David Golynkov, quoted in https://kozactvo-jimdofree-com.translate.goog/%D1%83%D0%B2%D1%96%D1%87%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%BC%D0%BE-%D0%BF%D0%B0%D0%BC-%D1%8F%D1%82%D1%8C-%D0%BE%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%BC%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B0/?_x_tr_sl=auto&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=wapp

[vii] Oleg Timkov, ‘Ataman Grigoriev: Truth and Fiction.’ https://kozactvo-jimdofree-com.translate.goog/%D1%83%D0%B2%D1%96%D1%87%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%BC%D0%BE-%D0%BF%D0%B0%D0%BC-%D1%8F%D1%82%D1%8C-%D0%BE%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%BC%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B0/?_x_tr_sl=auto&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=wapp

[viii] Smele, 98, 102

[ix] Arshinov, https://libcom.org/library/chapter-07-long-retreat-makhnovists-their-victory-execution-grigorev-battle-peregonovka-

[x] Arshinov

[xi] Deutscher, p 364