Listen to this post on Youtube or in podcast form

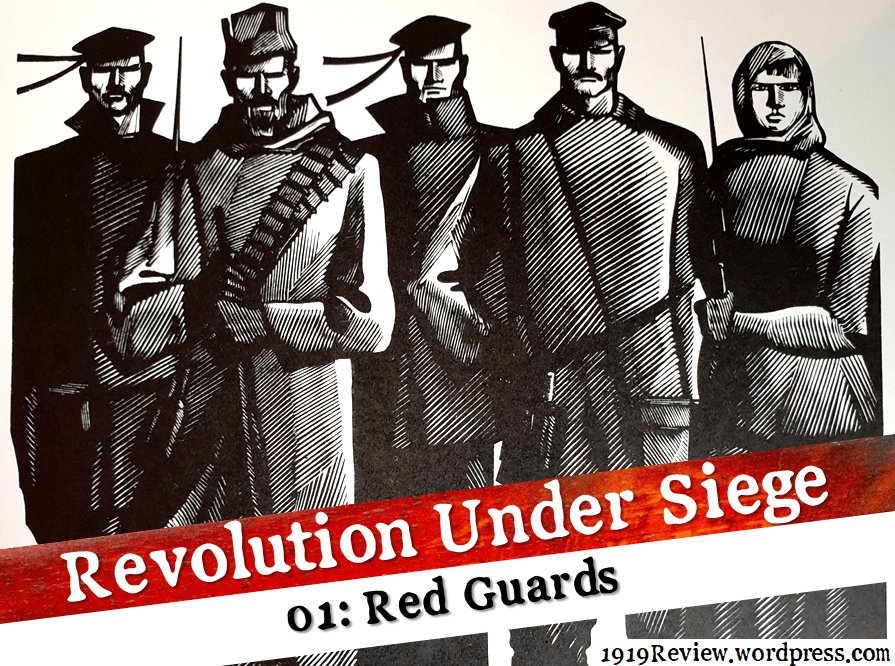

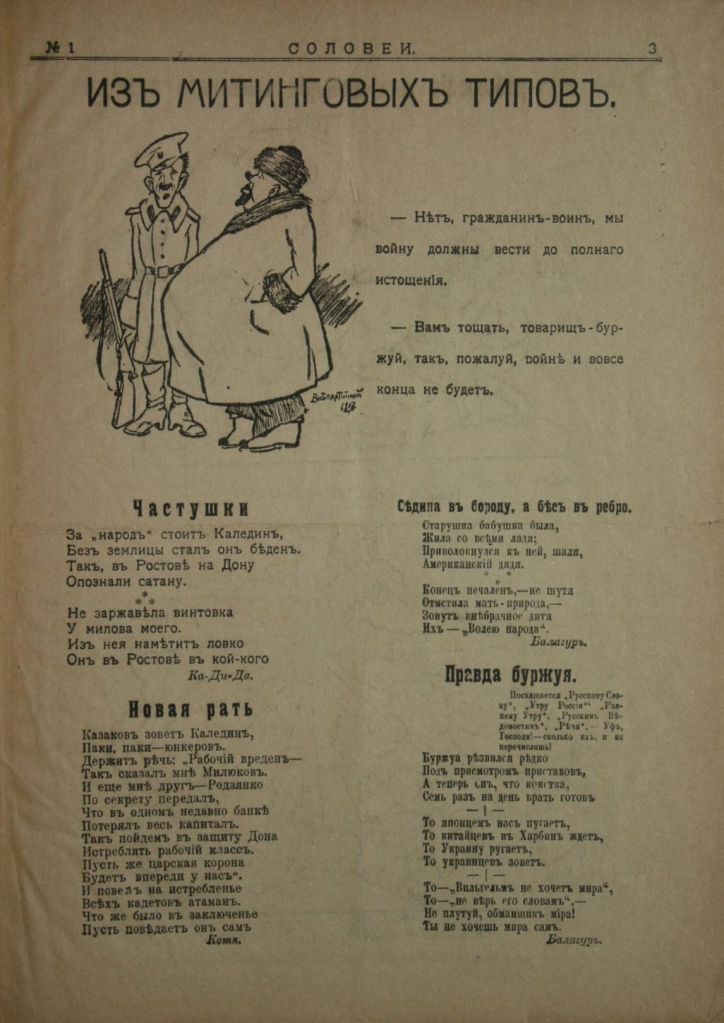

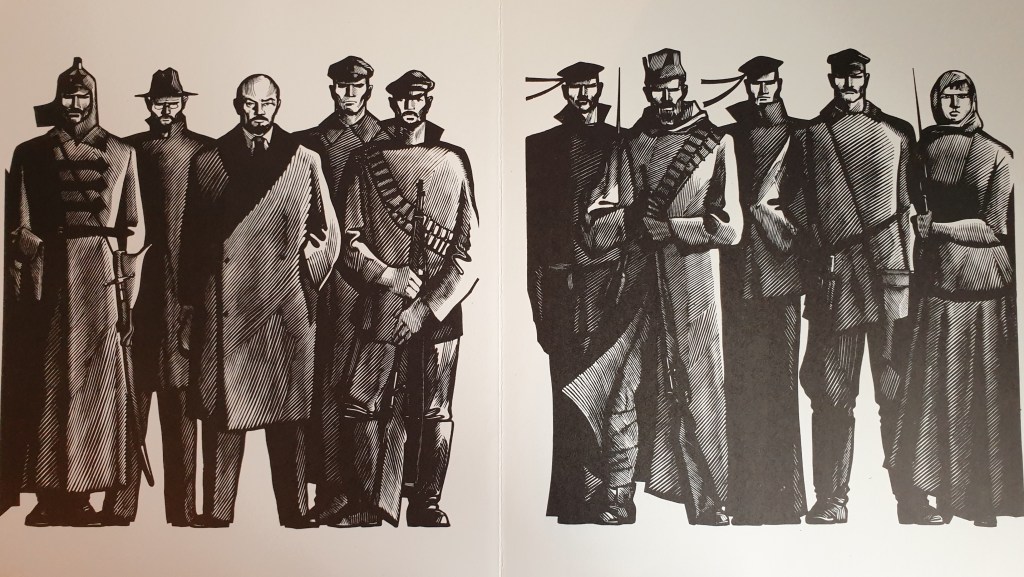

In November 1917, three hundred factory workers gathered in the village of Tushino near Moscow. One of them later recalled: ‘We faced a struggle against the Cossacks, and we workers had scores to settle.’[1] They held the rifles with which, one month earlier, they had fought for Soviet power. In Moscow they were given olive-khaki army gear and sent on by rail, with thousands of other armed workers, to Kharkiv. Of these thousands of armed passengers, many were in civilian clothes, others army jackets that had known Galician mud and German shrapnel. The closest thing to a common uniform was a red armband. Some wore a metal cap badge in the shape of a red star, some with a hammer-and-plough device. The hammer-and-sickle, which would become the symbol of communism in the 20th Century, had not yet caught on. The red star was, for some reason, worn upside-down. They wore ammunition belts criss-crossed over their chests. Bullets were scarce, and they wanted to keep them jealously in arm’s reach.

At Kharkiv, a city that was solid for Soviet power, they mustered before setting off for the southern extremity of European Russia. These were the Red Guards, the closest thing the Russian Revolution of October 1917 had to an army, and they were going to the country of the Don Cossacks and into battle.

One observer recalls the aspect of the Red Guards in these early months: ‘they still had a poor command of the rifle, and there was nothing to say about the bearing of a soldier [sic]. But on the other hand, fire sparkled in everyone’s eyes, everyone was full of courage.’

Another source describes the Red column under the former Tsarist officer Muraviev: ‘They were oddly dressed, totally undisciplined people, covered from head to toe with every kind of weapon – from rifles to sabres to hand-guns and grenades. Arguments and fights constantly flared up among their commanders.’[2]

These commanders were elected by the rank-and-file. Some of them were sergeants and corporals of the old army. Others were members of the radical left parties, the Left Socialist Revolutionaries and the Bolsheviks. Key decisions were taken at mass meetings.

The Red Guards, rising from the slums and shop floors, were going south to fight an army that was their opposite in every way. A force called the Volunteer Army, three or four thousand strong, had gathered by the Don River for one purpose: to crush the October Revolution. It was made up mostly of officers and cadets. Over one in five of these men were members of the hereditary nobility – who made up only 1.3% of the population at the time. It’s entirely possible that the Volunteer Army contained as many generals as privates.[3] They were known by a nickname that was just a few weeks old – the White Guards.

The Red Army as such did not yet exist, and the Volunteers were only the first and the smallest of the White Armies. But this campaign in the Cossack lands at the start of 1918 was like a caricature of the Civil War – an army without officers, squaring up to an army made up primarily of officers.

The Reds had a decisive edge in numbers, the Whites in expertise and discipline. But there was a third force which was native to those lands, and whose leaders were allied to the White cause. That third force was the Don Cossack Host.

In this chapter we’re going to look at the origin of the Red Guards, at how these armed factory workers ended up travelling far from home to fight the officers and Cossacks. In the next chapter we’re going to examine the origin of the White Guards, before telling the story of what happened when these two forces met.

To get a notification when that post drops, leave your email address here:

The Reds

We will begin by looking at three revolutionaries. Taken together they provide a portrait of the Red Guards and of the revolutionary milieu from which this army emerged.

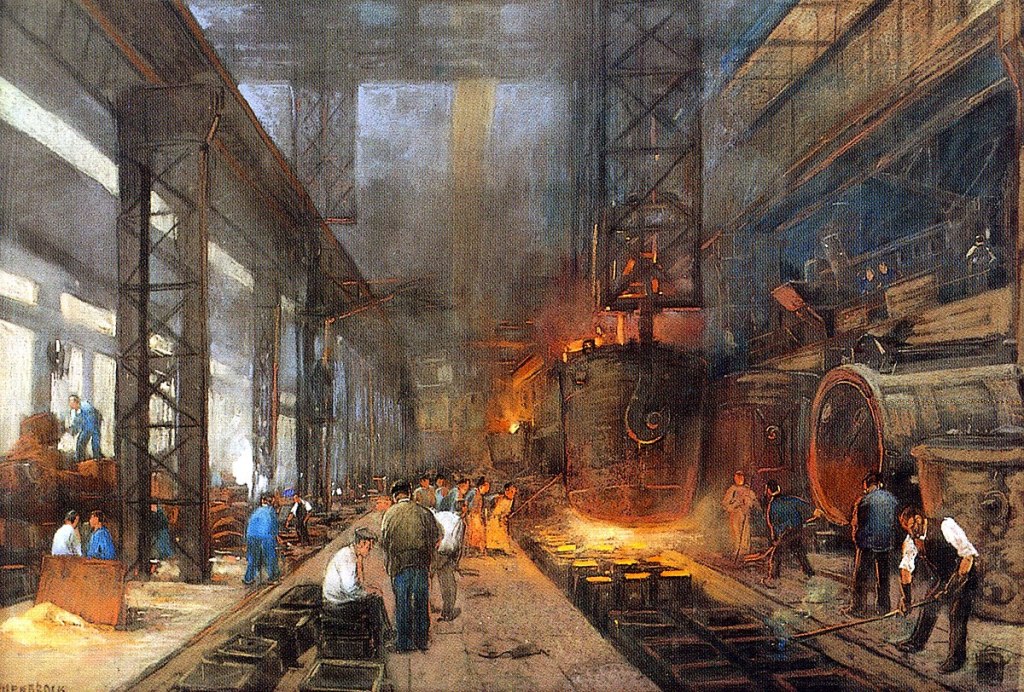

Kliment Voroshilov was typical of the Red Guards. His dad was a railway worker. He began his working life at age seven as a miner, then as a farm labourer under a ‘kulak’ (a wealthy peasant), then as a shepherd – all this before age 12, when he got a place in a village school. But by age fifteen he was toiling again, this time in a metal works. At seventeen he was under arrest for striking. In 1903, as a metal worker in the Hartmann Factory in Lugansk, eastern Ukraine, he came into contact with socialists. By 1918 he was a well-known workers’ leader in the Donbass region.

Vasily Chuikov was the eighth of twelve children of a peasant family, his mother a devout Christian on the staff of the local church, his father a bare-knuckle boxer. Chuikov finished his education at the age of twelve and moved to Saint Petersburg, where he worked in a factory that made spurs for cavalry officers.

Maria Spiridonova came from a well-off family. In 1906 she was enraged by the violence and sadism of a local official. So, she walked up to him one day and shot him dead. Police and Cossacks arrested her. There followed a notorious case which made headlines around the world: Spiridonova suffered torture, sexual assault, and finally a sentence of death commuted to life imprisonment. But with the Revolution came amnesty, and Spiridonova emerged as the leader of the Left Socialist Revolutionary party.

These individuals will feature again from time to time in the narrative that follows, but their main importance lies in the information about late imperial Russia and its revolution that can be gleaned from these biographical sketches.

In Western Europe the first generations of the working class were made up, by and large, of the children of artisans; the workers of Russia were the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of serfs. As late as 1917 a staggering number of them still owned land in some distant village.

There were illiterate oral poets of admirable genius who found machine work intolerable and who drifted from unskilled job to unskilled job; village youths stunted by malnutrition; commuters who, after their 10-14-hour day, got only a few hours in which to sleep; women who earned 15 kopeks a day before the war but 1.5 roubles during it; seasonal workers leaving behind their crafts or fields, barely understanding how wages and piece-work operated; foremen who were part of the worker-collective; white-collar workers who were outside it. During the First World War there were conscripted labourers from Central Asia, and Chinese workers brought in en masse by gangster-like contractors.

There were settled, established workers and recent migrants from the village. There were the workers of Petersburg, where gigantic metaland textile works employed thousands or tens of thousands, and there were the smaller workshops of the other cities. Even within the Petersburg steelworks, the fitters looked down on those in the foundry, the rolling-mill and the forge, whose faces ‘through the deep tan of the furnace’ appeared coarse.As late as the eve of revolution most workers still contributed their kopeks to buy oil for the religious ikon lamps that they kept in the corners of their workplaces.

The greatest concentration of workers was in Petersburg. (Saint Petersburg was later called Petrograd, then Leningrad). Working-class people lived three, four or five to a single-room apartment or to a cellar, paying high rents. Workers on different shifts would share a single bunk. Outside Petersburg it was common to sleep in a company-owned barracks. Shifts were ten, eleven, twelve hours. Overcrowding and overwork constituted mass and merciless social violence: 100,000 died in a cholera epidemic in 1900. One in four children died before they were a year old.[4]

Of course, there were things in modern city life that one could enjoy, even on low pay and long hours. Workers consumed the daily newspapers and illustrated periodicals with their ads and sensational stories. They read fiction about detectives and explorers and romance. Single working women spent one-fifth of their income on clothing, often employing seamstresses to copy fashionable styles. The young male metal worker, unless the strains of working life drove him into the trap of vodka addiction, would save up for a smart suit, a watch, a straw hat, and go out walking on a Sunday afternoon.

And there were, of course, political parties which offered solutions to the desperate conditions in which workers lived. There were the Social Democrats, a socialist party which split into the moderate, loosely-organised Mensheviks and the militant, tight-knit Bolsheviks (this split began in 1903 and culminated in 1912). Others looked to the peasant majority instead of the workers, or were inclined to a romantic rather than a scientific outlook. These would join the Socialist Revolutionaries, the SRs, a broad party with roots in the terrorist movement of the 19th Century. There were also Tolstoyans and Anarchists.

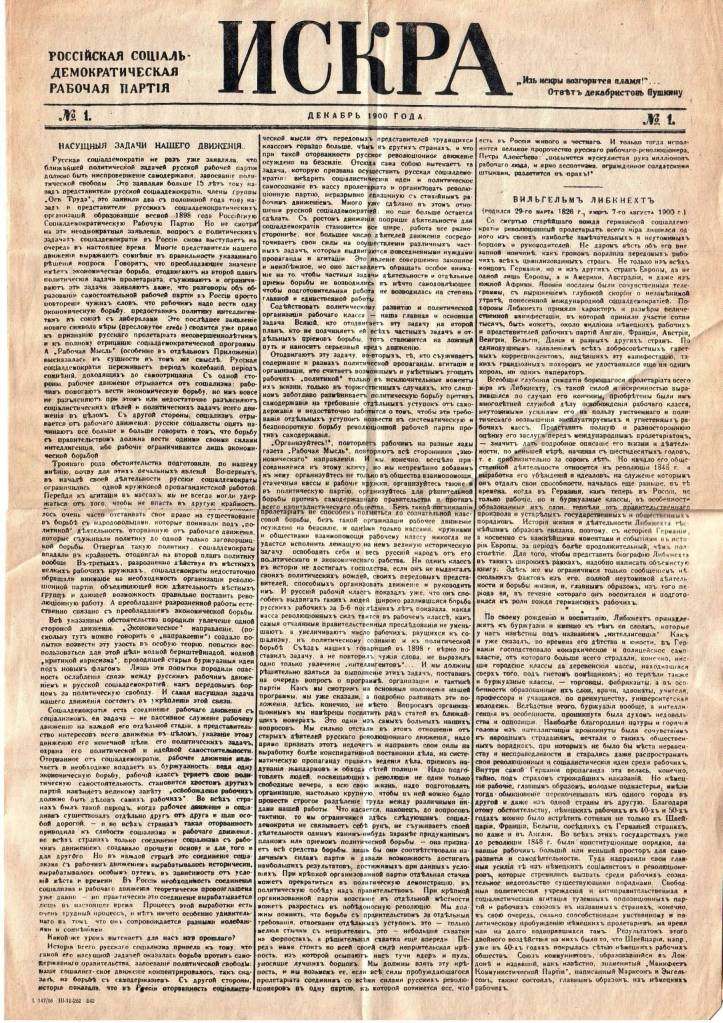

Three-quarters of people in the Russian Empire were illiterate, but a majority of workers could certainly read. ‘Every morning on the works train it was rare for someone not to read a newspaper or book, rare if you lived only for your wage and your family.’ They read Sherlock Holmes and Karl Marx and plenty in between. For some, ‘tales of Cossacks, of arrests and torture by the [secret police], of people hanged, and others forced to flee to some unknown destination became more interesting than adventure stories.’ [5] In the smoke and grime of factory and mining districts or in the noise and disorder of overcrowded housing, they would tackle the dense legion of words printed on thin paper under titles like Iskra, The Spark, Novaya Zhizn, New Life and RabocheyeDyelo, the Workers’ Cause. After political meetings, meditating on what they had learned, or on whatever fierce controversy had been aired, they would walk home along the unpaved, barely-lit streets of the working-class districts. In winter this would mean trudging in darkness through a river of mud.

The police, if they had reason to believe that a young man was a member of the Social Democrats, would arrest him and then play a simple trick that played on the psychology of party loyalty:

A prisoner’s mother, for example, would call on the colonel of gendarmerie and ask to be allowed a meeting with her son.

‘Well, you know, your son is accused of belonging to the Socialist-Revolutionary Party,’ the gendarme would say to her in a categorical tone.

‘Oh, come, Colonel,’ the mother would reply, in amazement: ‘my son has always been a convinced Social-Democrat.’

The gendarme would rub his hands with glee. That was all he needed.[5]

They risked it, because what was said in those meetings and what was printed on that cheap paper struck a chord with their own experiences, and offered a way forward. The bounty of nature and the great power of modern industry should not be in the hands of a wealthy few; they should be the collective property of the whole people. But the bosses and the state worked hand-in-hand to crush any strikes and protests. How to overcome the violent power of the state? The Social Democrats had an answer: the working class, through its decisive numbers in the big cities, through its control of production and transport, would bring down Tsarism.

But was it possible to build socialism in a country where two-thirds of the population were small property owners? Aid must come from advanced industrial countries, such as Germany. Germany was home to the most developed and impressive socialist movement in the world. On whom the Russian Mensheviks and Bolsheviks tried to model themselves. The revolution must be international, must embrace the industrialised countries of the West, or it would fail. But surely those advanced countries like Germany would have a revolution long before Russia ever got around to it.

Thoughts along these lines would have run through the head of the socialist worker as they negotiated the mud and open cesspits of the unlit streets. They would have wondered whether the working class could really defeat the system; whether the toiling people could really run and govern a country.

Revolution & Reaction

1905 was a year in which these questions were posed in real life. The workers of fifty towns and cities established councils directly elected from each workplace. These workers’ councils were known as Soviets, and in places they became parallel revolutionary governments. Workers formed defence groups to protect the Soviets, and these groups became known as Red Guards.

But the Russian army stayed loyal to the Tsar. 100,000 Cossacks were mobilised to crush the revolution by a charter that confirmed their privileges. Affluent liberals supported the revolution at first, but by the end of the year they were frightened and weary. They met the Tsar a lot less than half-way. There were disorders in the countryside, but by and large the cities were isolated.

The Tsarist government hanged 3,000 revolutionaries and killed more in various pogroms and repressions. There was street fighting in Łódź and Moscow; the Polish and Russian Red Guards fought bravely but it wasn’t enough to overcome a professional army.

Years of reaction followed. There were 410,000 members of state-sponsored ultra-right organisations and they were on a rampage. Jewish people were targeted for arson, looting and massacres; 600 anti-Semitic rampages took place.[7] Millions fled to Western Europe or North America. It was in this context that the above-mentioned Maria Spiridonova shot dead a Tsarist official.

The revolutionary parties were beaten down, disarmed and wracked with internal division. The Bolsheviks and Mensheviks made their split final. The SRs polarised into Left and Right but remained in one party. Their subsequent painful history proves that there are worse things in political life than splits.

But Tsarism had been forced to make some concessions on trade unions and elections. And the 1905 revolution had filled out abstract theory with concrete experience. The Soviets showed how the workers could form their own alternative government, their own participatory democracy, their own councils. On the other hand, the Red Guards had been no match for the army. The revolutionary worker had new questions to ponder, often from exile or a prison cell: could the insurgent people wage a successful civil war, or would the next revolution also be drowned in blood?

WAR

The First World War began in the summer of 1914. The horrors of modern warfare – machine-guns and apocalyptic artillery bombardments – were compounded by all the worst kinds of waste, incompetence, shortages and harsh discipline. The worker drafted into the army or navy found himself under an autocrat worse than the factory boss: the Russian officer, who was entitled to punch a soldier in the face, to humiliate him publicly, to spit on him. The Tsar’s regime was vicious both in defeat (Over a million people were banished from the borderlands as the Germans advanced) and in victory (A repressive anti-Semitic regime was installed in Lviv when it was briefly conquered).

The first tremor of revolution came in Central Asia. An attempt to impose conscription in 1916 triggered a rebellion. The army went in, killed an estimated 88,000 rebels and civilians, and sent 2,500,000 fleeing into China. According to Jonathan Smele, that was 20% of the population of Central Asia at the time.

In the big cities of European Russia, events in Central Asia were not at the forefront of the minds of working-class people. That place was occupied by the food crisis. The burden of feeding the army made an absolute mess of the food supply system, and the price of bread kept rising.

At first the war produced an atmosphere of patriotism that smothered all dissent. The Bolshevik Party, riding high in 1912-1914, had been reduced to 12,000 members by 1917. But the same patriotism fuelled indignation at the criminally poor leadership.

Nobody expected the Revolution of February 1917. Women workers in Petrograd triggered a decisive battle which drew in hundreds of thousands of participants and raged for five days. Each night the insurgent people would retire across the bridges to the working-class suburbs. Each morning they marched out again and resumed the struggle. They had few weapons so they used stones and even sheets of ice. They burned and looted police stations, beat and killed the police. Regiment by regiment, the soldiers of the garrison joined the revolution. This mutiny was decisive. The Tsar abdicated his throne and was imprisoned.

The key leaders of this movement ‘on the ground’ were the members of local committees of the various socialist parties, the workers who had trudged home after meetings and pored over Iskra sitting on their shared bunks in their overcrowded flats and cellars. They had torn down a 300-year-old dynasty in five days.

The power vacuum was filled by elements of the old regime and its tame opposition. They formed a self-appointed Provisional Government, and most people were inclined at least to give them a chance.

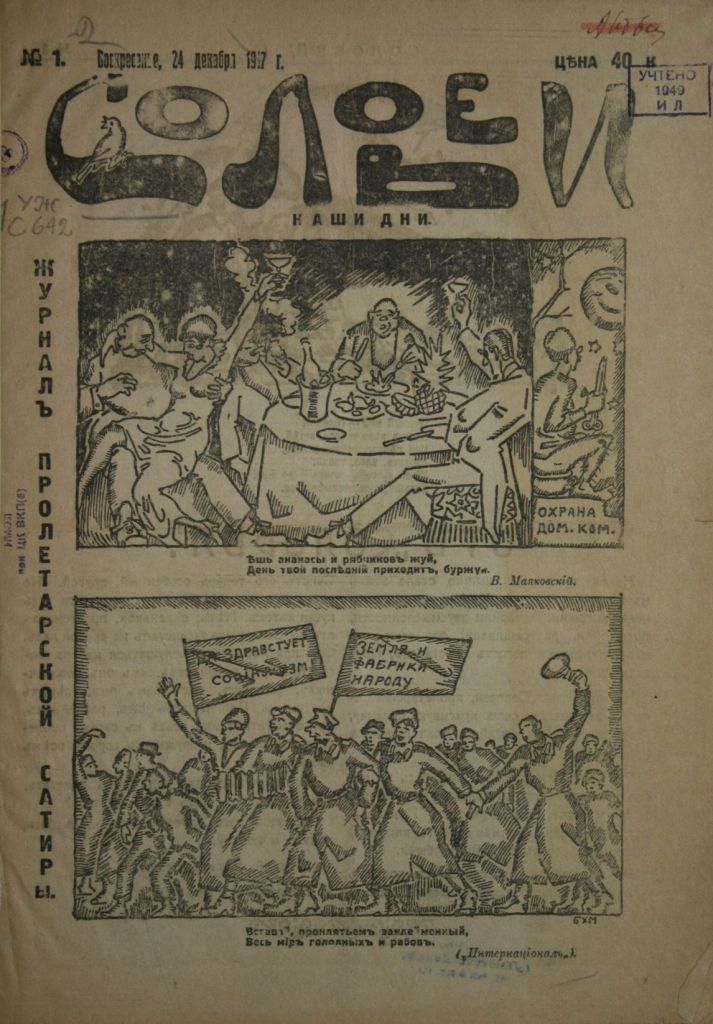

At the same time the Soviets, the great workers’ councils of 1905, re-emerged. They spread from Petrograd to every city and even to the regiments and villages, forming a brilliant system of participatory democracy – rough and ready, not yet embracing the entire population, but sensitive to the moods of the masses, reflecting the popular will at every turn. The delegates were subject to recall and re-election. In this honeymoon of the February Revolution, the Socialist Revolutionaries and Mensheviks had a decisive majority in the Soviet. Both supported the Provisional Government.

The key leaders of this movement on the ground were the members of local committees of the various socialist parties, the workers who had trudged home after meetings and pored over Iskra sitting on their shared bunks in their overcrowded flats and cellars. They had led their workmates and neighbours in tearing down a 300-year-old dynasty in five days.

The power vacuum was filled by elements of the old regime and its tame opposition. They formed a self-appointed Provisional Government, and most people were inclined at least to give them a chance.

At the same time the Soviets, the great workers’ councils of 1905, re-emerged. They spread from Petrograd to every city and even to the regiments and villages, forming a brilliant system of participatory democracy – rough and ready, not yet embracing the entire population, but sensitive to the changing moods of the masses. The delegates were subject to recall and re-election.

A local example can stand in for what was happening in many places: at the Provodnik works in Tushino near Moscow, a few dozen workers disarmed the factory guard. A mass meeting of workers and their families elected them as the new factory guard, the workers’ committee and the factory fire brigade, and sent delegates to the Moscow Soviet. Management soon found that the quickest way to procure supplies was via these workers and the Soviet system.[8]

In this honeymoon of the February Revolution, the Socialist Revolutionaries and Mensheviks had a decisive majority in the Soviet. Both supported the Provisional Government.

Hopes ran high at first and there was a mood of euphoria and national unity. But as the months passed the mood hardened. The Provisional Government was determined to continue the war. It was punishing those who dared to touch the property of the wealthy landowners. At factories whose workers were less vigilant than those at Tushino, bosses began lockouts, sabotage and threats of closure. The food situation got worse. Over the summer, the economy fell into crisis.

From April on, the Bolsheviks put forward a tough and clear position calling for the overthrow of the Provisional Government and for a socialist revolution. At first this was not a popular position, but as the summer wore on, those who had supported the Mensheviks and SRs switched to the Bolsheviks. Their slogans – ‘Peace, Bread and Land’ – ‘All Power to the Soviets’ – at first anticipated and then expressed the growing popular clamour.

The membership of the Bolsheviks rocketed from 12,000 to 350,000. In September, they won a decisive majority in the Soviet.

What had changed since 1905? This time, a mass movement of the rural toilers was sweeping the countryside, seizing the estates of the nobility, and the army was crumbling under the weight of desertions and mutinies.

What was Bolshevism? The name now carries all kinds of connotations, some very bad. But if we return to the factory in Tushino we get a different picture. This factory of five thousand had five hundred Bolsheviks as early as April and one thousand by September.

Staff at this factory organised a clubhouse on factory grounds where they had a library and a temperance society, an orchestra, amateur theatre, dancing, poetry and prose readings. Chekhov and Nekrasov were staples.

There was an entrance charge to all our social events, with the proceeds going either to victims of the old regime or to the library and other club facilities. It was always difficult to accommodate everyone who wished to visit the club. Artistic hand-drawn posters were put up in railway stations, workshops, villages, and hamlets a long way from the factory […] The whitecollar staff[…], who had formerly kept their distance from the workers, also came along to the theater, so the barrier between them and us began to break down spontaneously.

The working day was reduced to eight hours and all overtime was abolished, but the factory continued to operate and to produce as before the Revolution. [9]

The Red Guards

Vasily Chuikov, the son of the church secretary and the bare-knuckle fighter, found himself unemployed in Petrograd in 1917. But through one of his numerous brothers, he found something to occupy his time: he joined the Red Guards. In a few months’ time he would be shooting at cavalry officers, rather than making spurs for them.

The Red Guards had been re-founded by Bolsheviks, but they answered to the multi-party Soviet. They were armed with weapons seized from the burning police stations or factory security guards, or donated by workers in the war industries. Many had no weapons at all, and drilled with wooden sticks. Soon there were units in every ward of the city, some formed on a factory-by-factory basis and patrolling on company time. By July there were 10,000 members in Petrograd. After the failed coup by the right-wing General Kornilov in August-September the workers’ army numbered 20,000 in 79 factories. By November there were 200,000 nationally. They had pistols, rifles, the odd machine gun, even a few armoured cars. On duty, many Red Guards wore their Sunday best: their shirts, ties and waistcoats, watch-chains and fedoras or straw hats.[10]

Many soldiers and sailors supported the Red Guards. Kronstadt, home of the Baltic Sea fleet, was a rock-solid bastion of Bolshevik, anarchist and Left SR sailors.

Recruitment to the workers’ militia was as strict as to any other organization. The candidacy of each prospective member was discussed at a session of the factory committee, and applicants were often turned down on the grounds that they were regularly drunk or engaged in hooliganism or had behaved coarsely with women. [11]

By autumn, anxiety had settled on the Red Guards. Winter was coming. The economic crisis was getting worse, and famine was already a reality. Maybe the Bolshevik leaders were just like the other party leaders – all talk. Maybe the opportunity for revolution would pass. Maybe this movement would fall apart, and there would be hell to pay – a defeat bloodier and more total than that of 1905.

But on the night of October 24th-25th the Petrograd Red Guards were called out onto the streets.[12] The Provisional Government was attempting to shut down the Bolshevik newspaper. In response the Military Revolutionary Committee of the Soviet went on a long-planned offensive. The Red Guards and their soldier and sailor allies occupied the city. Rifles, machine-guns and cannon could be heard firing, but there was no real battle.

The Provisional Government waited in the Winter Palace as the Reds occupied the streets outside. The defenders of the Winter Palace consisted of cadets and the Women’s Battalion.[13]At first the cadets and women vowed to commit suicide sooner than surrender. But hours later, confused and demoralised, they let the Red Guards in with a shrug of the shoulders. It was less a ‘storming’ of the Winter Palace than a long confused siege merging with a gradual infiltration.

At last the defenders laid down their weapons. The Red Guards and soldiers, these children of serfs who had lived three to a cellar, ‘broke into the Palace and after rushing up the 117 staircases, through 1,786 doors and 1,057 rooms at last, at ten past two in the morning, entered the room where the ministers of the bourgeois Provisional Government were and arrested them.’[14]

The Reds inflicted no fatalities. Apparently they suffered six, two by friendly fire.[15]

The journalist Louise Bryant, following up a rumour, interviewed another casualty of that night, a young woman who was injured.

Well, that night when the Bolsheviki took the Winter Palace and told us to go home, a few of us were very angry and we got into an argument,’ she said. ‘We were arguing with soldiers of the Pavlovsk regiment. A very big soldier and I had a terrible fight. We screamed at each other and finally he got so mad that he pushed me and I fell out of the window. Then he ran downstairs and all the other soldiers ran downstairs…. The big soldier cried like a baby because he had hurt me and he carried me all the way to the hospital and came to see me every day.[16]

This is a human portrait, but not a very flattering one, of the soldiers of the revolution. The wider world was told a very different story: that the women were raped en masse. As late as 1989, western sources were still embellishing the original lie. We read (in Anthony Livesey, Great Battles of World War One, Marshall, London, 1989) that ‘The Bolsheviks, who hated them for wanting to fight to the end, raped, mutilated and killed any who fell into their hands.’ The second part is so outrageously false that it almost feels redundant to point out that the first part is wrong too; they didn’t fight to the end. In fact, they were ambivalent about the government they were defending.

After the Revolution

Who will govern us then?’ demanded one daily newspaper which appeared on the day of the October Revolution. ‘The cooks, perhaps […] or maybe the fishermen? The stable boys, the chauffeurs? Or perhaps the nursemaids will rush off to meetings of the Council of State between the diaper-washing sessions. Who then? Where are the statesmen? Perhaps the mechanics will run the theatres, the plumbers foreign affairs, the carpenters the post office. Who will it be?[17]

As if in answer, the Congress of Soviets was meeting at the Smolny Institute. The vast majority of the delegates approved of the insurrection. The Mensheviks and SRs, who had once commanded a majority, were now reduced to a rump. The Congress without delay passed decrees taking Russia out of the war, transferring the noble and church estates to tens of millions of peasants, and declaring the right of self-determination for nationalities. The new regime did in a few days what the Provisional Government had dragged its feet on for nine months.

In those days, Red Guards and sailors patrolling in the streets were harangued by well-dressed citizens who accused them of madness, anarchy, bloodthirsty violence, etc. The revolutionaries listened, sometimes puzzled, sometimes keenly interested, to their heated arguments and fabricated atrocity stories.

Before the year was out the revolution had spread to most cities and towns. The local Soviet would simply form a Military-Revolutionary Committee and take over. That’s not to say it was straightforward or peaceful. There was street fighting in Moscow and in Irkutsk, and a Cossack-cadet rising in Petrograd. The Red Guards won in each case. But already in October a counter-revolutionary army was gathering by the Don River. It was one thing to defend your own familiar streets. It was quite another to travel a thousand kilometres to the edge of Russia, the home turf of the notorious Don Cossacks, to fight a legion of officers. But there was nothing else for it. The Red Guards took up arms and went south to the Don.

In the next chapter we will look at the White Guards and the Cossacks and try to understand why they took up arms against the Revolution. Finally, we will look at what happened when Red and White met in South Russia at the start of 1918 in the first front of the Russian Civil War.

On the audio version, the music and transitions are as follows:

Music: From Alexander Nevskyby Sergei Prokofiev – ‘Battle on the Ice’

Battle sounds: From All Quiet on the Western Front, 1979, Dir. Delbert Mann. Youtube.com

Speech: From Young Indiana Jones Chronicles, Roger Sloman as Lenin. Youtube.com

[1]Dune, p 96

[2] The first quote is from AM Konev, The Red Guard in the Defence of October, available on the website Leninism.ru, describing Red Guards in Irkutsk. The second is from Smele, Jonathan. The ‘Russian’ Civil Wars 1916-1926, Hurst & Company, London, 2015 p 56, describing Red forces in Ukraine.

[3] There were ‘very, very few’ rank-and-file soldiers in the Volunteer Army – Serge, Year One of the Russian Revolution, (1930; Haymarket, 2015) p 123. We can make a list of 15 generals who were in the VoljnteerAmry in 1918: Pokrovsky, Erdeli, Ulagay, Shkuro, Kazanovich, Kutepov, Wrangel, Borovsky, Shilling, Lyakhov, Promtov, Slushov, Yuzefovitch, Bredov. From Khvostov, Mikhail and Karachtchouk, Andrei. The Russian Civil War (2) White Armies. Osprey Publishing, 1997 (2008) p 13-14

[4] Smith, SA. The Russian Revolution and the Factories of Petrograd, February 1917 to June 1918. Unpublished dissertation, 1980. University of Birmingham Research Archive, etheses depository. Pp 22, 53;

Smith, SA, Russia in Revolution, Oxford University Press, 2017, Chapter 2: From Reform to War;

Dune, pp 11-12

[5] Dune, pp 15, 19

[6] Raskolnikov, FF. Tales of Sub-Lieutenant Ilyin, 1934 (New Park, 1982), ‘DPZ’, https://www.marxists.org/history/ussr/government/red-army/1918/raskolnikov/ilyin/index.htm

[7] Foley, Michael. History of Terror: The Russian Civil War, Pen and Sword, 2018

[8] Dune, pp 36-7. 47

[9] Dune, 38, 40-41, 47

[10] Serge, Year One of the Russian Revolution, pp 68-70

[11] Dune, 51

[12] This date is going by the Julian calendar – the date by the Gregorian calendar was 6/7 November. In early 1918 the Soviet regime changed from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar.

[13] The Women’s Battalion was a unit of several hundred enthusiastic women volunteers for the war against Germany. To their frustration, they had been used for propaganda purposes and not sent into battle – until now.

[14] The USSR: A Short History, Novosti Press Agency PublishingHouse, 1975 p 109. This book is an interesting souvenir whose account of Soviet history is riddled with omissions.

[15] Taylor, AJP, The First World War: An Illustrated History. Penguin, 1963. (1982) p 200

[16]Bryant, Louise, Six Red Months in Russia, George H Doran Company, 1918. Available online athttps://www.marxists.org/archive/bryant/works/russia/index.htm

[17] Faulkner, Neil. A People’s History of the Russian Revolution, Pluto, 2017, p 209