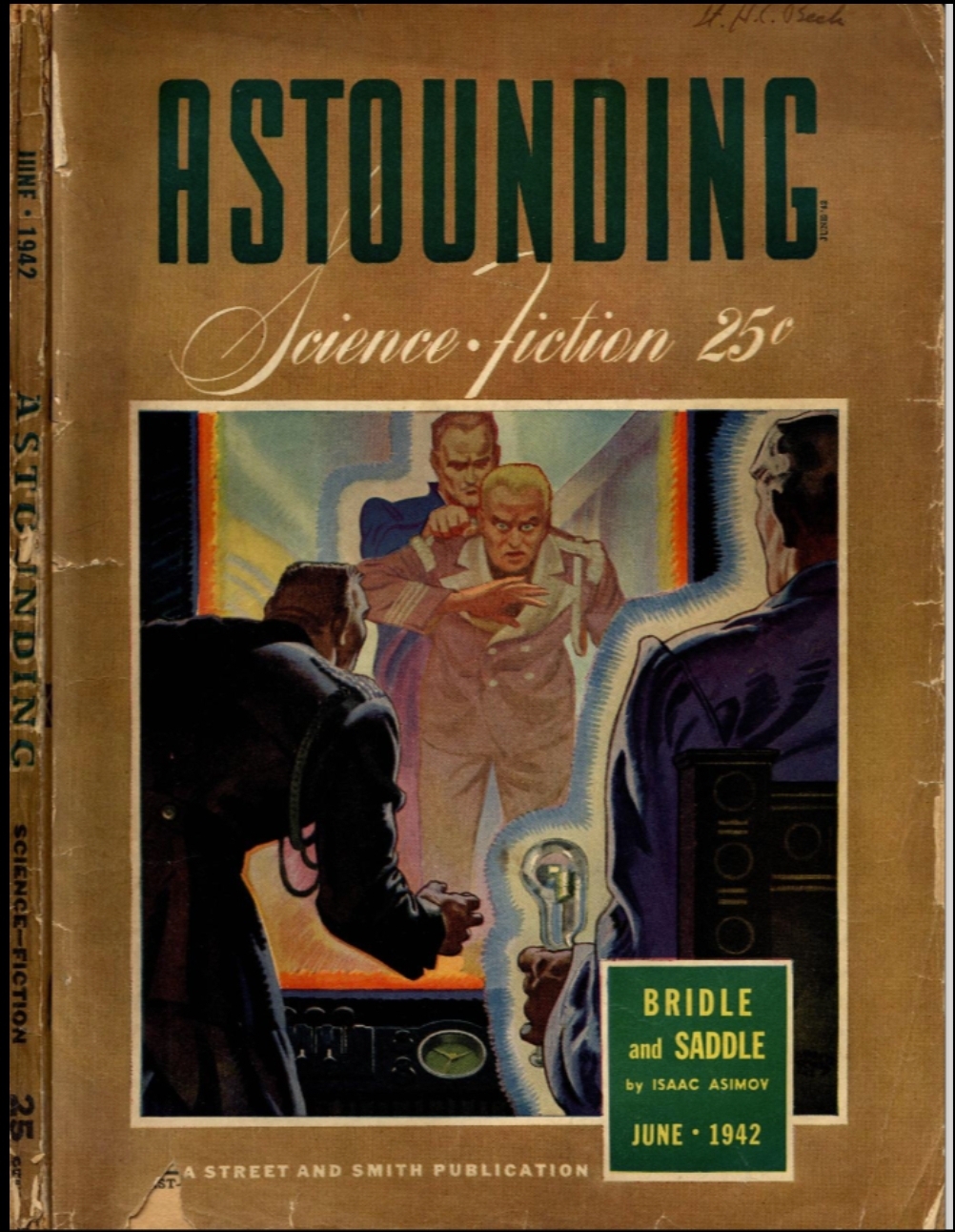

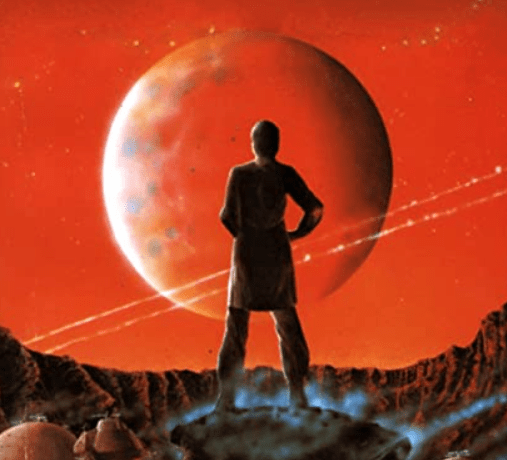

Second Foundation is the third volume of the original Foundation trilogy so before I get into it I’ll sum up what I wrote here on this blog about volumes 1 and 2, Foundation and Foundation and Empire.

I liked the deterministic mid-century materialism of Foundation. On the other hand, it could be smug and cynical and it was extremely of its time (imagine, someone probably died in combat on Iwo Jima knowing what the Seldon Plan was). It was quite dry, to-the-point, talky and minimalist.though it got more flashy and dramatic as it went on. Then at the midpoint of Foundation and Empire Asimov threw the old formula out the window. So long, mid-century determinist fable – don’t let the vast socio-economic forces hit you in the arse on the way out – it’s time for a fun swashbuckling adventure about a villain who can do mind control. This new formula boasted better characterisation and pacing, but overall I missed the tweedy old Foundation.

Second Foundation, like Foundation and Empire, contains two stories separated by a few decades. The first story concludes the story of the Mule, the psychic warlord introduced in the previous volume. He searches for and struggles with the Second Foundation. At last towards the end we get a glimpse of this mysterious institution.

Skirting around spoilers, we don’t see any more of the Mule in the next story. ‘Good,’ I said to myself. ‘We’re back on track. No more Space Yuri. We’re back to the Seldon Plan. Amoral characters as unwitting agents of vast historical forces. Empires hobbled by their own overextension. Kingdoms brought low by atomic hairdryers.’ But I ended up disappointed; this too was a story about psychic powers and mind control. We are focused on the Second Foundation in this story, and they just so happen to be a bunch of psychics like the Mule. Asimov labours to tie it in with the whole idea of psychohistory.

The Magneto in the High Castle

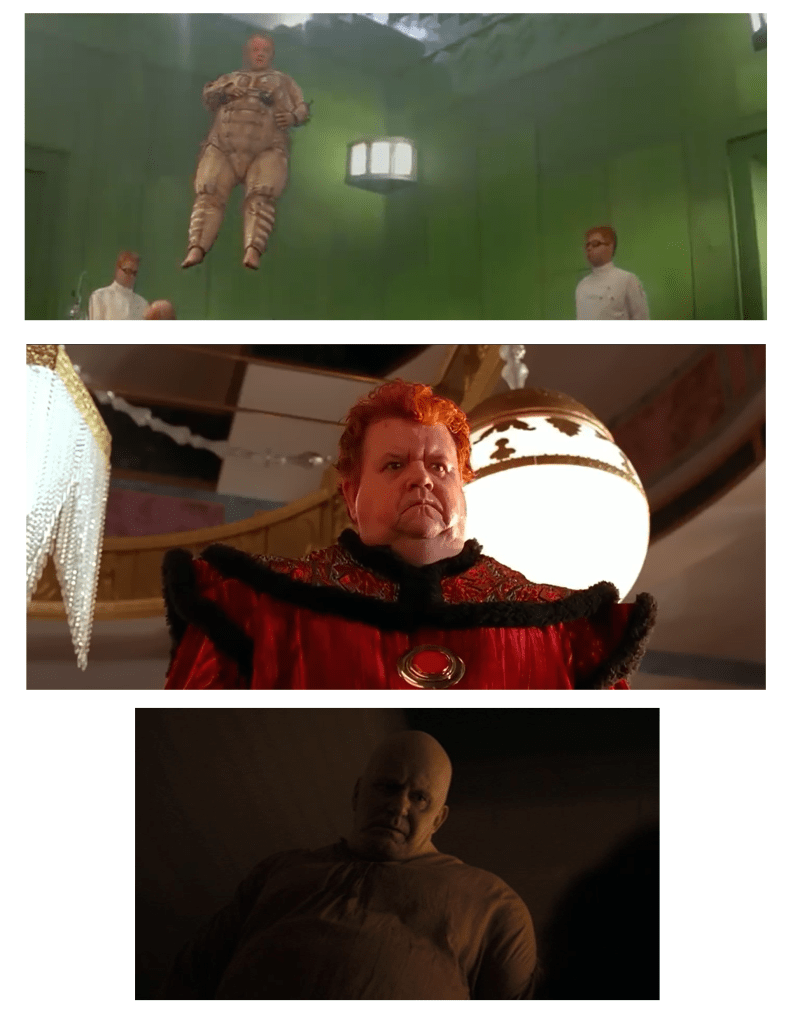

To get a sense of how I feel about this, imagine if half-way through The Man in the High Castle Philip K Dick had suddenly introduced Magneto from the X-Men. For the uninitiated, Magneto is, like the Mule, a mutant with special powers; he can control metal with his mind. So imagine if a good chunk of The Man in the High Castle is about Magneto picking up panzers and flinging them around squishing prominent Nazi leaders. Dick’s counterfactual 1960s Nazis are developing plastics, so I suppose they finally build a plastic tank and squish Magneto in turn. After Magneto is vanquished, there is one final episode in the story, concerning the Japanese Emperor, who it is revealed also has magnetic powers. Dick goes out of his way to explain this, somehow, with reference to the I Ching, in order to tie this absolute nonsense back into the original ideas of the story.

However fun this scenario would be, it would kind of distract from the fascinating questions that Dick uses his alternate history to ponder. To take another example, just for fun, imagine if half-way through The Dark Forest by Cixin Liu, when we are invested in wondering how humanity is going to hold off an alien invasion, the clouds part and Jesus descends, turns a lot of water into wine, and dies on a cross somewhere half-way through Death’s End.

This is kind of what happens with the original Foundation trilogy. Its second half is fun and not by any means devoid of the interesting ideas we find in the first half. The mysteries – where is the Second Foundation? Who are its secret agents? Who is its mysterious leader, the First Speaker? – are solid with good development and payoffs. But they are mechanical. They have more to do with the craft of storytelling than with the science of psychohistory.

And, I mean… no doubt Dick would have written Magneto pretty well too, and would have found some time to ponder the nature of reality itself in between the scene where Bormann gets squashed by a panzer and the scene where Goebbels gets boa constricted by a lamp-post. But it would still have been a wild and irrelevant departure from a promising story.

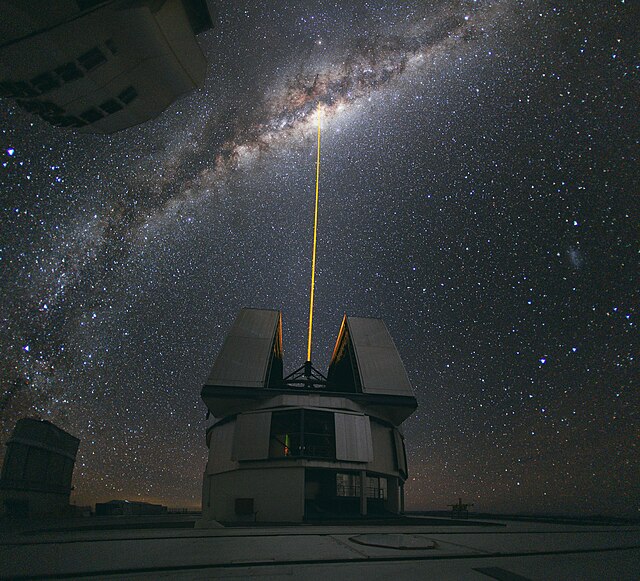

Acknowledgement: William Blair (Johns Hopkins University)

Motivations

The second half of this volume presented some problems for me, even aside from all that. In this story a group of private citizens from the Foundation are hunting for the Second Foundation, because some people’s brainwaves have started to show up a little strange on the mind-reading machines, and it is suspected that the Second Foundation is interfering.

The motivations of this group of private citizens don’t make much sense. The Second Foundation saved them and it is part of the Seldon Plan, which is their secular religion. And then during the story, agents of the Second Foundation save their arses again and again. The two Foundations have no basis for conflict at all. In spite of all this, our Foundation characters remain determined to root out the Second Foundation and its agents with extreme prejudice. Not only does it seem perverse, it doesn’t seem urgent at all. There is no existential threat to the Foundation here. The story lacks urgency, unless it is our desire to see how the Second Foundation will stop these gobshites, but the author doesn’t really commit to that either.

It gets worse (and spoilers follow). When the Foundationers identify one Second Foundation agent in their own circle, they immediately torture and restrain him (p. 229, 1994 HarperCollins Voyager edition). When the Foundation crowd believe they have found fifty agents of the Second Foundation, they do not take long to decide on their narrow range of options:

‘What will we do with all of them… these Second Foundation fellas?’

‘I don’t know,’ said Darell, sadly. ‘We could exile them, I suppose. There’s Zoranel, for instance. They can be placed there and the planet saturated with Mind Static. The sexes can be separated or, better still, they can be sterilized – and in fifty years, the Second Foundation will be a thing of the past. Or perhaps a quiet death for al of them would be kinder.’ (p 232)

A subsequent scene confirms that one of these fates has indeed befallen the fifty agents. Though we are not told which one, it hardly makes a difference!

The early-1950s viewpoint of the author offers some sources of interest and amusement, and, occasionally for me, mild disgust. But I was struck in a nice way by this description of an automatic ticket machine as a futuristic wonder:

‘You put a high denomination bill into the clipper which sank out of sight. You pressed a button below your destination and a ticket came out with your ticket and the correct change as determined by an electronic scanning machine that never made a mistake. It is a very ordinary thing[…]’ (p 169-170)

We have that now, and the only abnormal thing there is using cash instead of card. My knee-jerk reaction is to think, ‘how quaint.’ But on reflection, what prescience.

Conclusion

So that’s how I felt about Second Foundation: enjoyed it, recommend it, but expected more and felt it could have been more.

My verdict on the whole Foundation trilogy (I haven’t read the prequels and sequels written forty years later, so for me it is still a trilogy): “The General” in Foundation and Empire and the first few dozen pages of “The Mule” in the same volume represent a kind of peak Foundation for me. It’s lost some of the excessive dryness of the first volume without yet taking on all the extraneous psychic stuff. After this point, it never stops being entertaining or having good ideas; to its credit, it never retcons; and in some ways the writing improves… But it loses touch with its basic theme. The author seems to have lost interest in the question of predicting and planning the future through mathematics and psychology.

No wonder it ends unfinished, only half-way through Seldon’s thousand-year interregnum. Maybe that’s for the best. The rise of the Foundation into a new Galaxy-wide empire would not have been half as interesting as its early struggles for survival. Let’s remember the assumptions the series is built on: that empires are good and interregna are bad. Later stories would have had to go back and deconstruct a lot of that, if they wanted to remain thoughtful and interesting.